Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sylvestre Roberge WCVA2018

Uploaded by

Marina Cayetano EvangelistaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sylvestre Roberge WCVA2018

Uploaded by

Marina Cayetano EvangelistaCopyright:

Available Formats

ANESTHETIC EFFECTS OF KETAMINE-MEDETOMIDINE-

HYDROMORPHONE IN DOGS AS PART OF A HIGH-VOLUME

STERILIZATION PROGRAM IN BELIZE

SYLVESTRE-ROBERGE F1, MONTEIRO B2,3, SIMARD MJ4, STEAGALL PV2,3

1Hôpital

Vétérinaire des Laurentides, Québec, QC.

2Département de sciences cliniques, Faculté de médecine vétérinaire, Université de Montréal

3Groupe de recherche en pharmacologie animale du Québec, Département de biomédecine vétérinaire, Université de Montréal

4Fondation Aide Vétérinaire Internationale, Beloeil, QC.

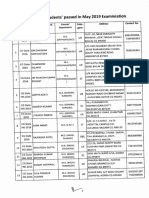

INTRODUCTION Table 1. Chart used for the calculation of total anesthetic volume of the “Doggy magic”.

Anesthesia for high-volume sterilization programs presents unique The patient’s body weight (kg) is represented in bold whereas the respective volume of

administration (mL) is in italics.†

challenges. Injectable anesthesia is often used, however limited information

1 0.12 3 0.40 5 0.68 7 0.95 12-13 1.5 21-23 2.3

is available on the prevalence of adverse effects.

1.5 0.17 3.5 0.46 5.5 0.74 7.5-8.0 1.0 14-15 1.7 24-25 2.5

The aim of this study was to describe the anesthetic effects of an injectable

2 0.25 4 0.52 6 0.80 8.5-9.5 1.2 16-17 2.0 26-27 2.7

anesthetic protocol in dogs included in a high-volume sterilization

program in Belize. 2.5 0.34 4.5 0.61 6.5 0.89 10-11 1.3 18-20 2.2

†The "Doggy magic" mixture has a total volume of 9.9 mL including 3.3 mL of ketamine (100

The hypothesis was that this protocol would offer effective anesthesia with mg/mL), 3.3 mL of medetomidine (1 mg/mL), 0.66 mL of hydromorphone (10 mg/mL) and

low prevalence of adverse effects in this specific context. 2.64 mL of sterile saline.

MATERIAL & METHODS RESULTS

Ethics committee protocol number: 18-Rech-1920

Rapid onset of lateral recumbency (3.2 ± 1.9 minutes) was recorded.

Study design: Prospective, cohort study Four dogs required additional administration of anesthetics during

Animals: Thirty-five client-owned, free-ranging dogs (8 males and 27 surgery.

females; 13.7 ± 7.6 kg; ≥ 8 weeks-old) from two mobile clinics in rural Belize Return of swallowing reflex and time to standing were 71.9 ± 23.6 and

were included. Dogs could be pregnant or in estrus. 152.8 ± 52.3 minutes after injection, respectively.

Return of swallowing reflex was significantly longer in heavier dogs.

Anesthesia and surgery: A volume-based protocol entitled “Doggy magic” Mean ± SD were 110 ± 18 mmHg for MAP, 85 ± 19 bpm for HR and 19 ± 8

was administered using a pre-established chart according to the patient’s rpm for RR throughout the procedure.

body weight (Table 1). Dogs received approximately 4.5 mg/kg of ketamine,

0.04 mg/kg of medetomidine and 0.09 mg/kg of hydromorphone IM. Hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90%)2 was observed at least once in 65.7% of dogs

and was significantly more frequent in heavier dogs.

Anesthetic monitoring: Following physical examination and anesthetic

Hypoventilation (FE’CO2 ≥ 50 mmHg)2 was observed in 45.7% of dogs.

induction, dogs were intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube and

Hypertension (MAP ≥ 120 mmHg)2, bradycardia (HR ≤ 60 bpm),

allowed spontaneous breathing in room air. Monitoring included SpO2,

tachycardia (HR ≥ 140 bpm) and hypothermia (≤ 36.5°C)3 were observed

MAP, SAP, DAP, HR, fR, rectal body temperature and FE’CO2. Meloxicam

in 40%, 14%, 2% and 2%, respectively.

(0.2 mg/kg SC) was administered at the end of surgery. Adverse effects

Sex was not significantly associated with any complication.

were monitored throughout the procedure (Figure 1a,b,c,d).

Pain assessment: The Glasgow canine pain score (CMPS)1 was used for the Mean CMPS scores were 2.7 ± 2.1. Four dogs (11.8%) had scores ≥ 6. It is

assessment of postoperative pain up to 4 hours after the end of surgery. not known if they were actually painful or if scores were influenced by

demeanor and/or residual anesthetic effects.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed with linear models and chi-square

tests (p < 0.05).

FIGURES CONCLUSIONS

The combination of ketamine, medetomidine and hydromorphone was

effective for the majority of dogs undergoing sterilization.

Hypoventilation, hypoxemia and prolonged recovery were commonly

observed.

Oxygen supplementation, assisted ventilation, intraperitoneal and

intratesticular blocks and drug antagonism should be considered as part

of high-volume sterilization programs using similar anesthetic protocols.

Further studies are warranted to assess perioperative pain management

using injectable anesthesia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Fondation Aide

Vétérinaire Internationale for their support

REFERENCES

1. Reid J, Nolan AM, Hughes JML, et al. Development of the short-form Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale

Figure 1. Anesthesia in a high-volume sterilization program in Belize. (CMPS-SF) and derivation of an analgesic intervention score. Animal Welfare 2007; 16:97-104.

a. Anesthetic monitoring used in the study 2. Ramos RV, Monteiro-Steagall BP, Steagall PV. Management and complications of anaesthesia during balloon

b. Set-up for anesthesia and surgery valvuloplasty for pulmonic stenosis in dogs: 39 cases (2000 to 2012). Journal of Small Animal Practice 2014; 55:207–212

c. A dog is undergoing general anesthesia for ovariohysterectomy 3. Redondo JI, Suesta P, Serra I, et al. Retrospective study of the prevalence of postanaesthetic hypothermia in dogs.

Veterinary Record 2012; 171:374

d. Anesthetic recovery in dogs

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 2 Step PPD FormDocument1 page2 Step PPD FormWilliamNo ratings yet

- ARDS Concept Map - BunayogDocument2 pagesARDS Concept Map - BunayogJacela Annsyle BunayogNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia GravisDocument11 pagesMyasthenia GravisParvathy RNo ratings yet

- Îeéuwûéaéié Uréékéï: (Diseases of Tongue)Document87 pagesÎeéuwûéaéié Uréékéï: (Diseases of Tongue)Pranit Patil100% (1)

- 4D CT With Respiratory GatingDocument2 pages4D CT With Respiratory GatingLaura Karina Sanchez ColinNo ratings yet

- Infection Control in ORDocument10 pagesInfection Control in ORaaminah tariqNo ratings yet

- Retinal Drawing: A Lost Art of MedicineDocument2 pagesRetinal Drawing: A Lost Art of MedicineManuel GallegosNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Abomasal DiseaseDocument16 pagesSurgical Management of Abomasal DiseaseAbdul MajeedNo ratings yet

- Management of Severe Hyperkalemia PDFDocument6 pagesManagement of Severe Hyperkalemia PDFCarlos Navarro YslaNo ratings yet

- List of PG Students' Passed in May 2019 ExaminiationDocument4 pagesList of PG Students' Passed in May 2019 Examiniationyogesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Injury Patterns in Danish Competitive SwimmingDocument5 pagesInjury Patterns in Danish Competitive SwimmingSebastian VicolNo ratings yet

- Dentistry: A Case of Drug - Induced Xerostomia and A Literature Review of The Management OptionsDocument4 pagesDentistry: A Case of Drug - Induced Xerostomia and A Literature Review of The Management OptionsSasa AprilaNo ratings yet

- Nitrous Oxide Sedation DentistryDocument16 pagesNitrous Oxide Sedation DentistryAnonymous k8rDEsJsU1100% (1)

- Adrenal Gland: Bardelosa, Jesse Gale M. Barretto, Alyssa Nicole 3MT1Document88 pagesAdrenal Gland: Bardelosa, Jesse Gale M. Barretto, Alyssa Nicole 3MT1Alyssa Nicole BarrettoNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Adult With Epistaxis - UpToDateDocument29 pagesApproach To The Adult With Epistaxis - UpToDateAntonella Angulo CruzadoNo ratings yet

- 1.7 Surgery For Cyst or Abscess of The Bartholin Gland With Special Reference To The Newer OperatasDocument3 pages1.7 Surgery For Cyst or Abscess of The Bartholin Gland With Special Reference To The Newer OperatasMuh IkhsanNo ratings yet

- Anti InflamasiDocument27 pagesAnti InflamasiAuLia DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Additional RRLDocument3 pagesAdditional RRLManuel Jaro ValdezNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Structural Family TherapyDocument2 pagesRevisiting Structural Family TherapyKim ScottNo ratings yet

- Viva 1Document500 pagesViva 1Jan Jansen67% (3)

- Medrobotics Receives FDA Clearance For ColorectalDocument2 pagesMedrobotics Receives FDA Clearance For ColorectalmedtechyNo ratings yet

- About DysphoriaDocument5 pagesAbout DysphoriaCarolina GómezNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat Apotek KumaraDocument36 pagesDaftar Obat Apotek Kumaraigd ponekNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of RHDDocument4 pagesPathophysiology of RHDshmily_0810No ratings yet

- Manual - Glucometro TRUEresultDocument82 pagesManual - Glucometro TRUEresultSoporte Técnico ElectronitechNo ratings yet

- Brittany 2Document4 pagesBrittany 2Sharon Williams75% (4)

- MCQ Final 2014Document19 pagesMCQ Final 2014JohnSon100% (1)

- What Are NightmaresDocument2 pagesWhat Are NightmaresCharlie BalucanNo ratings yet

- Heart Block and Their Best Treatment in Homeopathy - Bashir Mahmud ElliasDocument13 pagesHeart Block and Their Best Treatment in Homeopathy - Bashir Mahmud ElliasBashir Mahmud Ellias50% (2)

- Osteoporosis PhilippinesDocument3 pagesOsteoporosis PhilippinesMia DangaNo ratings yet