Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Social Dimension of Invasive Plants - Lesley Head

Uploaded by

Benjamín HizaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Social Dimension of Invasive Plants - Lesley Head

Uploaded by

Benjamín HizaCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW ARTICLE

PUBLISHED: 6 JUNE 2017 | VOLUME: 3 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 17075

The social dimensions of invasive plants

Lesley Head

Invasive plants pose a major environmental management issue. Research into the social dimensions of this issue has flourished

over the past decade, as part of the critical examination of relations between human and nonhuman worlds. The social sci-

ences and humanities have made substantial contributions to conceptualizing invasiveness and nativeness; understanding the

perceptions, attitudes and values of diverse stakeholders; and analysing the politics and practices of invasive plant manage-

ment. Cultural analysis allows areas of conflict and commonality to be identified. Social complexity must be added to ecological

complexity to understand the causal relationships underlying invasions; and linear understandings of science–policy relation-

ships are too simplistic. Productive connections have been established between recent social and natural science approaches in

the context of rapid environmental change and unpredictable futures. Nonetheless, the prevalence of human exceptionalism in

the ecological sciences constitutes a major point of divergence between social and natural science perspectives.

I

nvasive plants are a major environmental management issue, from the “applied” or “interdisciplinary”) conservation social sci-

becoming more severe under climate change and socioeconomic ences19. For natural scientists looking for instrumental outcomes in

globalization1–4. Much of the debate within the invasive plant sci- the form of direct applications to policy and management, research

ences focuses on the effectiveness of current policy settings and that analyses and challenges foundational concepts can seem irrel-

management strategies5,6. Challenges include inadequate policy evant, if not downright annoying. Yet such “reflexive” contributions

commitment, lack of long-term funding, gaps in scientific knowl- (one of seven types of contributions identified by Bennett et al.19)

edge and the complexity of managing across increasingly fragmented are at the heart of social science contributions to invasive plant

land tenure landscapes7–9. Yet potentially rapid shifts in ecological research because the conceptual issues are so profound. The social

boundary conditions10 challenge environmental policy and govern- research reviewed here can also potentially assist with “diagnosing”

ance mechanisms developed for conditions of predictability 11,12. In why certain policies succeed or fail and be “generative” of innovative

the broader environmental sciences, as well as the invasive plant sci- or alternate approaches19.

ences specifically, it is now widely recognized that the sciences that Further, as Sandbrook et al. note in their admittedly simplistic

attend explicitly to people are essential to the task at hand13,14. Here, but useful distinction between social research “for” and “on” con-

I review the flourishing of social science and humanities perspec- servation, there are parallel distinctions in the natural sciences, for

tives on invasive plants, particularly over the past decade. example between applied conservation biology and “long-term eco-

The research reviewed here comes from a variety of disciplines, logical studies that challenge ideas of nativeness and demonstrate

particularly human geography, anthropology and history 15,16. These the socially constructed nature of restoration targets and conserva-

disciplines use diverse methods, including archival and documen- tion baselines”20. New archaeological techniques have shown human

tary analysis, discourse and media analysis, ethnography, quanti- influences on environments over long timescales to be more subtle

tative surveys and in-depth qualitative interviews. These methods and variable than previously thought 21, prompting considerations of

draw out and analyse discourses, attitudes, practices, norms, val- the extent to which our contemporary dilemmas are substantively

ues, concepts and policies. The human subjects of study include different to those of the past 10, or part of a continuum22. These paral-

farmers, pastoralists, gardeners, environmental managers, indig- lel trends in both natural and social sciences enhance the potential

enous and local communities, scientists, policymakers and the for convergence.

general public.

Social research into the field of invasive plant ecologies should be Conceptualizing invasiveness and nativeness

understood as part of the wider critical social sciences and humani- At the heart of many debates around invasive plants—or, indeed,

ties examination of relations between human and nonhuman worlds invasive species more broadly—are a set of contested and entan-

over the past several decades. An important contribution of this gled concepts: nature, native, alien, exotic, introduced, weed. These

work has been to help break down the division that social scientists entanglements come to the fore in debates between social and natu-

only study people, while natural scientists only study the nonhuman ral scientists23–27, and between natural scientists themselves28–30. Part

world. The work includes critique of the concepts of nature and cul- of the communication gap between natural and social science lies

ture, while also analysing how deeply these concepts are embedded in their respective approaches to such concepts. Within the natural

within Western thought and social structures17. Traditions some- sciences, these are terms to be defined in objective and unemotional

times referred to as ‘posthumanist’ critique ‘the human’ as an essen- language31, and categorized in a way that enables objective eco-

tialized and unified category, and argue for relational approaches logical and biogeographic study, and precise comparisons between

whereby the characteristics of phenomena are constituted in the studies32,33. Within the social sciences, by contrast, the terms are

process of their relationships with other phenomena, including understood as concepts that have lives of their own and need to

entanglements between humans and other species18. Most of the be followed as they stabilize, change, are contested, and become

research discussed here is undertaken in the “classic” (as distinct embedded in policies.

School of Geography, University of Melbourne, Melbourne 3053, Australia. e-mail: lesley.head@unimelb.edu.au

NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants 1

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEW ARTICLE NATURE PLANTS

There can be frustration between these approaches—it can feel as remarked-on feature of the concept as discussed in the humani-

though the natural sciences are trying to close things down while the ties and social sciences23,40–44. Using historical legal analysis, Chew

social sciences appear determined to open them up. Experimental and Hamilton argued the concept to be both recent and theoreti-

sciences seek to hold constant as many variables as possible, to facili- cally incoherent43. A further expression of the tensions inherent in

tate comparison between different studies. In the parts of the social such bounding practices is that humans are conceptually separated

sciences focused on here, it is difference itself that is the object of even from their food; “most humans rely on alien species for the

interest; hence, depth and context are vital. In the interests of more bulk of their requirements for food and other basic requirements”32.

productive conversations across the natural/social science boundary, Note, however, that a nuanced defence of the concept of nativeness is

it is important to explain why much social scholarship critiques cat- advanced by some45.

egorizations (of plants and humans) and exposes the political nature If the concepts of nativeness and alienness are contested, it is well

and assumptions underlying them34. An important contribution of recognized in both the natural and social sciences that species are only

these approaches is to examine how particular knowledge becomes alien with respect to specific places and times. This recognition is in

accepted as common sense. large part due to the dynamic and detailed long-term changes now

To say something is a concept or a discourse is not to give it any visible through palaeoecology 46. The issues of spatial and temporal

less material reality than plants, soil or climatic conditions. Concepts demarcation47 are worth attending to separately.

and discourses have power—in science, legislation and policy, and in As nativeness is defined in relation to the absence of human inter-

the mobilization of resources to kill invasive plants. Reliance on words vention, the temporal threshold against which it is measured var-

and labels inevitably makes any scientific discipline, including inva- ies according to how long different people have been in a particular

sion biology, a cultural practice, with its concepts having discursive region and how well the human history is known. In Britain, native

impacts that extend far beyond its immediate concerns35. Ecological species can be those in place prior to the last ice age48, although

policies “reflect in complex ways” the underpinning social values Scottish definitions focus on the pre-Neolithic, about 6,000 years

in their generating societies34. In invasive species policy framings, ago23. In Germany, the periods pre- and post-1500 ce (representing

metaphors of competition, war and security continue to be perva- the influence of the Columbian exchange) are considered differently 49.

sive36–38. Part of the debate might be over the relative effectiveness of In countries with shifting political borders, the timeframes can be

such metaphors, but we can surely agree that they exist. Material out- explicitly arbitrary, as in Norway’s year zero of 1800 ce50. In colonial

comes include the privileging of some species over others, in different contexts such as Australia, the moment of European colonization

spatial contexts23. is chosen, notwithstanding that indigenous peoples had consider-

Take, as example, the definitions provided in Pyšek and able (albeit less visible) influence on plant distributions for millennia

Richardson’s summary 32: before that39. In places such as Europe, the arbitrary nature of such

• Alien species: those whose presence in a region is attributable to boundaries is widely acknowledged, but in colonial contexts they tend

human actions that enabled them to overcome fundamental bioge- to be taken as self-evident and real.

ographical barriers (synonyms: exotic species, non-native species). The spatial configuration of nativeness has several dimensions,

• Invasive species: alien species that sustain self-replacing popula- discussed in both natural and social science literature. It is partly a

tions over several life cycles; produce reproductive offspring, often question of scale: is a species considered native to a vegetation com-

in very large numbers at considerable distances from the parent munity, a broader ecosystem or landscape, or a continent? But further,

and/or site of introduction; and have the potential to spread over political boundaries and processes are inevitably woven into both

long distances. the conceptualization of nativeness and the governance structures

• Native species: taxa that have evolved in a given area without by which invasives are managed. The same organism can belong to

human involvement or that have arrived there by natural means, different categories in different places (Table 1), and categorizations

without intentional or unintentional intervention of humans, can change over time—as in Iceland, where natural scientists have

from an area in which they are native. been on both sides of a debate over the case of lupins47. Historical

To make these distinctions workable, exemptions are necessary— analysis is thus an important part of exploring shifts in attitude and

for example, the usually smaller category of invasive natives. A strong practice. In the example of Acacia, movements are understood to be

theme in the social science literature has been to explore what such not just movements of the plant, but also accompanying bundles of

definitions and their associated practices say about understanding knowledge and technology, received into different social, political

humanness and the ways in which humanity is conceptualized as and economic contexts40. A further spatial demarcation of relevance

separate from nature. So, in the definition of alienness, the human is between urban and rural contexts, with most research focusing on

species is distinguished from biogeographic processes. In the defini- the latter. An emerging literature draws attention to the importance

tion of nativeness, humans are counterposed against natural means, of urban contexts51, where some pragmatic coexistence with invasives

and are separated from other processes of evolution. In an exchange will need to be tolerated52.

between social scientists and ecologists, Warren emphasized the role An important example in which temporal and spatial demarcations

of humanness in the definitions of nativeness and alienness, and play out is in the process of colonialism. It is no accident that both the

thus questioned the validity of the concepts23. Respondents argued ecological impacts32 and social science literature are strongly focused in

inter alia that the human role is essential in understanding processes postcolonial settler states such as the USA, Canada, South Africa53–55,

of invasion (a point agreed on by all authors) and defended the Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. This is partly because of the

human as a delineator in the definitions for this reason (the bone of dramatic ecological changes wrought by colonial processes, making

contention)24,25. There is disagreement within ecology about how well many parts of the world more prone to plant invasions through land

founded the concept of nativeness is39, with some arguing that the clearing and habitat loss. Such processes included not only “the bio-

distinction between native and non-native does not provide guiding logical expansion of Europe”56, but also more multidirectional plant

principles for environmental management28. But if it does have bio- movements, including dispersal back to the metropolitan centres40.

logical justification, nativeness is defined in terms of the influence of The social science and humanities literature on plant invasions is

the human. Native plants are defined in terms of human activities and part of the broader analysis of the links between Western environ-

influences, not in terms of the plants themselves. mentalism and the so-called Edenic sciences (including invasion

This point may seem unremarkable to ecologists and biogeogra- ecology)57, both of which hark back to a pre-colonial baseline of

phers, but it is very striking to others. The absence of a fundamen- pristine nature58. Indeed, it is argued that the concept of indigeneity

tal biological meaning for the concept of nativeness is the most itself—whether applied to humans, plants or animals—is a structural

2 NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

NATURE PLANTS REVIEW ARTICLE

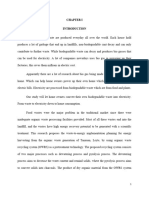

Table 1 | The perceptions, practices, times and locations of Australian Acacia.

Perceptions Practices When and where

Colonial—improving nature Acclimatization British colonies (E. Africa, S. India) 1820s onwards

Soil rehabilitation French Colonies (Algeria, Madagascar), 1900s onwards

Timber provision South Africa (Transvaal), throughout 1800s

National—productive landscapes Industrial planting Portugal, late 1800s until mid-1900s

International trade South Africa, post-1910

Symbolic appropriation Brazil, post-1940s

People-centred—sustainable development Agroforestry South Africa (Dept. Water Affairs and Forestry)

Community initiatives Vietnam’s afforestation strategies

Poverty alleviation Dominican Republic’s acacia woodlots

Ornamental—botanical symbolism Urban landscape design Mediterranean Europe, Southern France

Home gardening California

Wilderness protection Chile

Invasion biology—objective science Biodiversity conservation South Africa

Environmental control New Zealand

Ecosystem service protection Portugal

Global redistributions of the plant are understood here in relation to diverse perceptions, which are consequently used in different modes of practice. Data summarized from ref. 55.

outcome of colonialism59. If humans are acknowledged as always environments. They also have outcomes on the ground; whether

already involved in the world—and thus inseparable from it—then favourable or unfavourable, such responses play a major role in the

no such concept is needed. ‘Indigeneity’ can then be seen as a mani- treatment of different species in different contexts35.

festation of the structure of settler colonialism and the disruptions of In a world where policy is expected to be evidence based63, the

belonging that it entailed. Further, historical perspectives on particu- relationship between expert (scientist or manager) and lay (public)

lar invasive plants show that settler colonialism was less monolithic attitudes and knowledge is important. There are many more stud-

than often understood; analysis of prickly pear in Queensland empha- ies of the latter, and comparative studies are still emerging, perhaps

sizes the important role of non-white settlers60. because of ongoing assumptions that the purpose of studying public

Fall suggests that because this literature is in English and widely attitudes is to remove barriers to the execution of policy as developed

read, the colonial perspective in fact speaks back to and has influenced by experts, rather than to consider both experts and the public as

wider debates around invasive species34. This important argument groups who have cultures that need to be understood.

warrants further research. Scientists are shown in some studies to be more normative than

In summary, there is widespread recognition in both the social the public. The latter tend to respond on the more experiential basis

and natural sciences that, in principle at least, the framing of inva- of their engagement with plants, being more emotional and attached

sive plants is both spatially and temporally contingent. This has led to individual plants64. In a Swiss example, scientists concerned about

to many calls for management to be concerned about invasiveness (a gardening practices that encouraged invasives discussed their own

quality of plant behaviour, in relation to other organisms and condi- strategic decisions to focus on plants causing health problems, thus

tions) rather than nativeness or its absence (a categorization of the generating ‘social anxiety’ that was seen as a way of getting their

plant). Or, more precisely, to be as specific as possible about exactly point across and provoking action65.

what is considered problematic in that behaviour rather than using Increasingly, however, there is evidence of nuance and common-

broad generalizations such as ‘invasive’61. Nevertheless, the distinction ality in expert and lay judgments. Survey research in Scotland and

between invasive and native is still used in ecological discussion and Canada has shown that neither experts nor the public judge species

operationalized in management62. primarily on their origins66. Questions of nativeness are not per-

The purpose of this Review Article is not to render the relevant ceived as unimportant, but abundance and perceived damage are

concepts redundant or useless. Rather, being rigorous in their analy- considered to be of greater significance. Whereas professionals tend

sis helps ground scientific practice in more realistic approaches. The to make blanket judgments about non-native species in line with

social research discussed here clearly demonstrates that the concepts their approach to risk management, the public make assessments on

at the heart of invasion biology are fluid and contestable terms, framed each case, based on potential harm67. These studies illustrate path-

using human bounding practices. They are, for this reason, culturally ways for collaboration and mutual understanding, if viewpoints are

and emotionally freighted terms. The historical evolution of these discussed openly before management programmes commence.

concepts is closely tied with human governance structures including Survey research among invasion biologists themselves shows

colonialism and nationalism. Science has been part of this complex agreement that the level of current invasion is unprecedented, disa-

evolution and is not separable from it. In such a context, being rigor- greement that invasion is the second biggest threat to biodiversity,

ous requires working with this messy reality rather than trying to strip and agreement that hyperbole should be avoided68. There is a range

it away in tighter definitions. of views about how much emotional connection is needed to engen-

der debate among the broader community. Scientific perceptions of

Understanding perceptions, attitudes and values aggressive invaders can persist in the face of biogeographical evi-

A major contribution of social research into invasives has been to dence to the contrary 69. The social sciences can help the plant ecology

document the diversity of perceptions of (and attitudes to) invasive community make sense of the strong emotions that they articulate

plants, and the different aesthetic responses among different com- themselves as experiencing 70. These include the tensions between

munities. The same taxon can occasion different perceptions and describing the world as it is and shaping it as they want it to be, and

be valued differently across these different contexts (Table 1). These the co-existence of strong emotions with rational scientific practice57.

cultural dimensions are of interest in their own right, illustrating Although indigenous voices and values have been historically

diverse environmental imaginaries and ways of interacting with underrepresented in invasive species scholarship71, there is now an

NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants 3

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEW ARTICLE NATURE PLANTS

emergent body of work in this field. Within indigenous worldviews the in legislation and policy, and attitudes and perceptions flow into

scientific categories of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ species—themselves practice. The many challenges of translating science into policy are

partly a product of colonialism, as argued above—do not necessar- exacerbated in a “value pluralistic world”94. The need to understand

ily make sense. Nor should all indigenous communities be expected diverse values and experiences is acknowledged for different reasons.

to respond in the same way. Non-native species are welcomed in In some cases, the native/alien dichotomy is rejected as a manage-

some contexts72, although this can change over time73. The depth and ment principle95; in other cases, the need to involve stakeholders is a

complexity deducible via anthropological research is well evident in more pragmatic choice as social and political support is understood

Martin and Trigger’s59 study of the culturally diverse meanings and as critical to the sustainability of invasive species management 13,63.

historical relationships around individual Australian trees, including Note that, as outlined in the introduction, this paper does not

one commonly perceived as an iconic native (Eucalyptus coolabah), provide a full review of the social sciences of invasive plant govern-

and another as potentially invasive (Cocos nucifera). ance, as might be found in the political and legal sciences. (Albeit

In many parts of Australia, indigenous communities have become some of the mainstream governance literature has noted the difficul-

important partners in invasive plant management, with indigenous ties posed by the “ambiguity” of the concept of invasive species96,97.)

rangers key to the labour force74. Different members of communities This section focuses on explicit analyses of the practice of invasive

have been shown to talk and act differently in relation to invasives plant management, including the ways it is entangled with politics.

in Western Australia’s Kimberley region. Aboriginal elders use a dis- The broader framing of biosecurity, which has become the

course of caring for country, whereas younger Aboriginal rangers use “master frame” for policy and debate around ecological threat

a warlike discourse because of their European science-based train- (whether human-, animal- or plant-based) and the mitigation of

ing 75. These diverse views affect how the two groups view success— associated risk98, provides useful context to the present discussion.

the latter are disappointed by their inability to kill all plants. Biosecurity governance provides another example of how temporal

The category of ‘local knowledge’ is usually applied to rural and spatial demarcations to which organisms belong play out at dif-

communities, often trying to maintain agricultural livelihoods. ferent scales. “Biosecurity cannot be seen as a purely technical chal-

Management strategies vary with how particular plants are valued, lenge. Rather it is a highly contested geopolitical process that cannot

for use or other attributes76. Study of these strategies helps elucidate be disentangled from the risks perceived and posed by different

the social processes influencing invasion—for example, the vary- stakeholder groups”63.

ing approaches over time to the management and cultural value of Complex geopolitics emerge in the tensions between neoliberal

Typha domingensis (cattail) and Schoenoplectus californicus (bulrush) priorities of unimpeded international trade, and what is required for

in Lake Pátzcuaro, Mexico77. Examples include attempts to incor- effective biosecurity governance. There are contradictions between

porate the knowledge of marsh hayers into understanding the pro- our widespread desires to move people and goods freely, while

cesses of invasion of Phalaris arundinacea (reed canary grass) in the simultaneously constraining all sorts of organisms99. The World

American Midwest78. Local knowledge is sometimes used together Trade Organization itself recognizes that global trade poses a bio

with ecological surveys to document change over time, as in the security risk, but argues that policies to control this risk need to not

Eastern Cape, South Africa, where local elders were interviewed about restrict trade98. Put differently, “environmental invaders are an exter-

their knowledge of Lantana camara invasion, a process that has been nality of global trade”100, not least the nursery industry 101.

detrimental to medicinally and ritually important forest tree species79. Questions of biosecurity are closely linked to the scale of the

A research focus on gardens and gardeners is particularly relevant nation state, the operational unit within global agreements such as

because many invasives started life as garden plants transferred from the Biodiversity Convention. In order to protect biodiversity, signa-

one place to another in the process of human migration. Gardeners tories must produce national lists of invasive species. This can make

today can be seen as vectors in the flow of potential invasives at ecological sense when the national border corresponds with a sig-

two key points: the purchase of plants and the dumping of garden nificant terrestrial ecological boundary, as in the cases of Australia

waste into neighbouring bushland80. A survey study in southeastern and New Zealand85, but is more complex in the case of continen-

Australia demonstrated the important role of commercial nurseries tal Europe, with the many national boundaries and complex gov-

(and minor role of environmental initiatives) in purchasing deci- ernance agreements of the European Union (EU)102,103. Further,

sions, which tended to prioritize the appearance and aesthetics of some have argued that EU actions are hindered by the ongoing

plants. This is consistent with a well-documented trend in Australia perception of Europe as a source of, rather than a destination for,

that shows vernacular preferences for exotic gardens, or mixed invasive species104.

gardens of natives and non-natives, rather than native species81,82. Regardless of intention, biosecurity approaches intensify the

Norwegian gardeners are not at all concerned about the native/non- long-observed links between nation, nature and identity 34,105. In

native status (as defined in Norwegian environmental management) Aotearoa New Zealand, for example, the governance processes that

of their plants, but are concerned about their behavioural attributes, produce good ecological citizens function at the level of the indi-

such as invasiveness83. Even then, invasiveness is not necessarily seen vidual, who has legal obligations to participate in surveillance and

as bad, provided it is within certain bounds of garden control. Similar reporting of invasives, or who is mobilized against transgressions of

attitudes are reported in Sweden84. the border, as in the case of community ‘Weedbuster’ teams85.

An important theme across many of these studies is the emotional The diversity of attitudes and values reviewed in the previous sec-

and embodied entanglements between people and plants, as their tion take one expression in the policy world as the views of ‘stake-

interactions unfold in diverse contexts relevant to invasiveness85–88. holders’. The need to involve diverse groups is better recognized with

These emotions connect to wider thinking about change and stability respect to invasives in agriculture, and biosecurity around human

in nature89. In contrast to humanist perspectives that have historically disease, than in the literature regarding invasive plants in wild-

emphasized the agency and power of human beings, empirical evi- lands13,100,106. At one level, it may seem obvious that the role of human

dence has led many social scientists to recognize the agency of plants. values is strongly acknowledged in more overtly human activi-

Studies illustrate the dynamic relations that emerge as plants accom- ties, but this simply highlights the exceptionalist case of the wild-

modate, cooperate with or struggle against human aspirations90–93. land examples. It also helps explain, for example, why many more

resources are invested in managing invasives that threaten agricul-

Analysing management politics and practice tural production than those of purely environmental concern98.

The types of studies discussed in the previous sections have impli- An expanding methodological literature discusses practical

cations for invasive plant management, as concepts are expressed examples of how to develop and improve methods for stakeholder

4 NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

NATURE PLANTS REVIEW ARTICLE

mapping 107, including structured decision making 106. Knowledge of Whether this is between different stakeholders or between expert

stakeholder attitudes can have contrasting applications, as two dif- and lay perspectives, constructive pathways forward depend on

ferent studies in Spain showed. A study in Galicia108 showed overlap- clear understanding of differences and commonalities in meanings,

ping attitudes to the main invasive plants among key stakeholders, norms and resultant practices. The alternatives offered by cultur-

contributing to the potential for consensus building about appropri- ally different approaches to invasive plants could yet be seen as an

ate actions. In another context 109, researchers found remarkably dif- important resource in times of rapid change.

ferent perceptions about impacts and benefits, leading to the need to The addition of social complexity to ecological complexity fur-

consider trade-offs for action between different positions. ther undermines the notion of single causes or drivers. There is

Social factors can be analysed as both enablers and barriers to potential for both social and natural science perspectives to better

management of invasives110. As in the above cases that show both integrate multiple drivers of change into their thinking. The broad-

conflict and commonality, stakeholder mapping studies do not in ening of socioeconomic and political processes exemplified here

themselves answer the inherently political question of whose views has some parallels with the extension of the concept of species

should count more, and in what contexts. Relevant political pro- invasiveness to community invasibility 118. Invasive networks119 and

cesses operate at multiple scales. For example, invasive buffel grass assemblages120 are useful frameworks that can accommodate the

(Pennisetum ciliare) in Mexico’s Sonoran Desert is influenced by both complexity and contingency evident in both social and ecological

political economic structures (international relations of production domains. Indeed policy may be a relatively minor lever of change

in feeder calf manufacture) and the behaviours (rational and irra- in some contexts.

tional) of individual ranchers, in addition to ecological factors111. The The expectation that the problems of invasive plants can be

use of glyphosate as a management strategy can quickly create tech- solved with a linear translation of good science into policy is an

nological lock-in and loss of knowledge about alternative methods112. overly simplistic framing, quite inconsistent with the complex-

Changing patterns of land use and amenity migration have made the ity illustrated in these works. More contingent and provisional

management of serrated tussock (Nassella trichotoma) more difficult stabilizations are likely. Science is used in complex ways and these

in southeastern Australia8. Moreover, attention to questions of trust processes themselves require ongoing analysis. There are varying

and power is vital to scale-up effective management from individual responses to social approaches in the natural science community,

landholders to a collective landscape or ecosystem scale113. particularly when ecologists themselves may be uncomfortable

An emergent body of work is undertaking explicit analysis of the being the subject of research. However, there should be much to

practices of invasive plant management. One widespread finding is welcome for ecologists in this work, including understanding

that there is a high degree of reflexivity in the practice of invasive that their own emotional responses are not incompatible with

plant management, that is, that the experience of interacting with rational research.

plants changes people’s perceptions of them. Examples include the Living with and killing invasive plants involves political and eth-

science of biocontrol114, and the management of gorse (Ulex spp.) in ical choices. Discourses of war are at odds with much invasive plant

Aotearoa New Zealand85. In contrast to continued policy metaphors management practice and need to give way to a more nuanced

of war and battle36, the actual practice of management shows consid- understanding that we both live with and kill plants in different

erably more nuance and subtlety, albeit sometimes in tension with contexts. A more honest acknowledgement of the cultural bases of

policy 115. Interview research with Typha managers in Mexico not historical decisions may also help us have more explicit discussions

only drew attention to diverse and practical knowledge but also sug- around the political and ethical dilemmas of invasive plant man-

gested improved management practices77. Some studies show that agement. In some contexts the many positive features and consid-

collaborative participatory methods such as citizen science mapping erable adaptive potential of invasive plants need to be recognized35.

of non-native invasives can enhance management success116. Much of the social research cited here attempts to go beyond

Overall, the complexities outlined in this section challenge any human exceptionalism, and aspires to contribute “more creative

presumption that management is a simple process of increasing adaptations to changing environments into the future”59, in which

awareness, or that people just need to be educated to do the right humans are considered as existing within nature rather than apart

thing according to a dominant scientific view 35. from it. Ongoing (and incomplete) social science and humanities

attempts to include humans and nature in the same conceptual

Implications and convergent pathways framework stand in stark contrast to the separationist definitions

This concluding section summarizes the key contributions of social prevalent in invasion ecology. However, they do have some features

research and identifies productive connections (actual or poten- in common with those parts of ecology and biogeography attempt-

tial) with natural science approaches. The issue of invasive plants is ing to conceptually and empirically include humans, for example

here one example of the wider challenges of global environmental the concepts of novel ecosystems121 and anthropogenic biomes

change, with increased levels of uncertainty and high potential or anthromes122.

for surprise over the coming decades. Environmental governance For many ecologists interested in invasive plant management,

frameworks developed for relatively stable conditions will be chal- social processes constitute complications: stumbling blocks or bar-

lenged by climate change117. riers that must be removed for effective action to occur. Social sci-

The spatial and temporal variability identified in studies of both entists on the other hand are more likely to regard complication as

plant movements and people’s understandings of where they belong normal, and plant transfers as integral to “the human process of

affirms that both nativeness and invasiveness are unstable, evolv- regional differentiation”40. Messy complexity is not something that

ing concepts35. Rather than attempt to pin the concepts down, sci- can be ignored, but part of the world we are trying to understand

entists and policymakers need to realise how they are understood and live in. That is not to say that difference does not exist, nor that

and expressed in different times and places. Across many different categories are not useful—rather, the ways they are constituted and

groups of people, experiential engagements with plants have been take effect are empirically open questions to be studied in diverse

shown to be an important influence on attitudes and practice. Focus contexts. This commitment to empirically grounded research is

on the behaviours of plants (in combination with wider assem- perhaps the most important shared characteristic that enhances

blages), rather than on pre-defined categories, will lead to more social and natural science connections.

productive outcomes.

The depth and diversity identified using cultural analysis allows Received 26 September 2016; accepted 26 April 2017;

areas of conflict and compatibility to be more clearly identified. published 6 June 2017

NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants 5

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEW ARTICLE NATURE PLANTS

References 36. Larson, B. M. in Body, Language and Mind (eds Ziemke, T., Zlatev, J.

1. McGeoch, M. A. et al. Global indicators of biological invasion: species numbers, & Frank, R. M.) 169–195 (Mouton De Gruyter, 2008).

biodiversity impact and policy responses. Divers. Distrib. 16, 95–108 (2010). 37. Barker, K. in Spaces of Security and Insecurity: Geographies of the War on Terror

2. Barbour, E. & Kueppers, L. M. Conservation and management of ecological (eds Ingram, A. & Dodds, K.) 165–184 (Routledge, 2009).

systems in a changing California. Clim. Change 111, 135–163 (2012). 38. Downey, P. O. Changing of the guard: moving from a war on weeds to

3. Driscoll, D. A. et al. Priorities in policy and management when existing an outcome-orientated weed management system. Plant Protect. Quart.

biodiversity stressors interact with climate change. Clim. Change 26, 86 (2011).

111, 533–557 (2012). 39. Bean, A. R. A new system for determining which plant species are indigenous in

4. Capinha, C., Essl, F., Seebens, H., Moser, D. & Pereira, H. M. The dispersal Australia. Austral. Syst. Bot. 20, 1–43 (2007).

of alien species redefines biogeography in the Anthropocene. Science 40. Kull, C. A. & Rangan, H. Acacia exchanges: wattles, thorn trees, and the study of

348, 1248–1251 (2015). plant movements. Geoforum 39, 1258–1272 (2008).

5. Carboneras, C., Walton, P. & Vilà, M. Capping progress on invasive species? 41. Sagoff, M. Who is the invader? Alien species, property rights, and the police

Science 342, 930–931 (2013). power. Soc. Philos. Policy 26, 26–52 (2009).

6. Johnson, D. S. Making waves about spreading weeds: response. Science 42. Lien, M. E. & Davison, A. Roots, rupture and remembrance the Tasmanian lives

344, 1236–1237 (2014). of the Monterey Pine. J. Mater. Cult. 15, 233–253 (2010).

7. Simberloff, D., Parker, I. M. & Windle, P. N. Introduced species policy, 43. Chew, M. K. & Hamilton, A. L. in Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology: The Legacy of

management, and future research needs. Front. Ecol. Environ. 3, 12–20 (2005). Charles Elton (ed. Richardson, D. M.) 35–48 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

8. Klepeis, P., Gill, N. & Chisholm, L. Emerging amenity landscapes: invasive weeds 44. Hattingh, J. in Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology: The Legacy of Charles Elton

and land subdivision in rural Australia. Land Use Pol. 26, 380–392 (2009). (ed. Richardson, D. M.) 359–375 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

9. Epanchin-Niell, R. S. et al. Controlling invasive species in complex social 45. Mastnak, T., Elyachar, J. & Boellstorff, T. Botanical decolonization: rethinking

landscapes. Front. Ecol. Environ. 8, 210–216 (2010). native plants. Environ. Plan. D 32, 363–380 (2014).

10. Steffen, W., Grinevald, J., Crutzen, P. & McNeill, J. The Anthropocene: conceptual 46. Willis, K. J. & Birks, H. J. B. What is natural? The need for a long-term

and historical perspectives. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 369, 842–867 (2011). perspective in biodiversity conservation. Science 314, 1261–1265 (2006).

11. Duit, A. & Galaz, V. Governance and complexity—emerging issues for 47. Benediktsson, K. Floral hazards: Nootka lupin in Iceland and the complex

governance theory. Governance 21, 311–335 (2008). politics of invasive life. Geogr. Annal. 97, 139–154 (2015).

12. Lemieux, C. J., Beechey, T. J. & Gray, P. A. Prospects for Canada’s protected areas 48. Jones, O. & Cloke, P. Tree Cultures: The Place of Trees and Trees in Their Place

in an era of rapid climate change. Land Use Pol. 28, 928–941 (2011). (Berg, 2002).

13. Larson, D. L. et al. A framework for sustainable invasive species management: 49. Pyšek, P., Richardson, D. M. & Williamson, M. Predicting and explaining plant

environmental, social, and economic objectives. J. Environ. Manage. invasions through analysis of source area floras: some critical considerations.

92, 14–22 (2011). Divers. Distrib. 10, 179–187 (2004).

14. Marshall, N. A., Friedel, M., van Klinken, R. D. & Grice, A. C. Considering the 50. Setten, G. in Nature, Temporality and Environmental Management:

social dimension of invasive species: the case of buffel grass. Environ. Sci. Pol. Scandinavian and Australian Perspectives on Peoples and Landscapes

14, 327–338 (2011). (eds Head, L., Saltzman, K., Setten, G. & Stenseke, M.) 30–44 (Routledge, 2017).

15. Rotherham, I. D. & Lambert, R. A. Invasive and Introduced Plants and 51. Francis, R. A. & Chadwick, M. A. Urban invasions: non-native and invasive

Animals: Human Perceptions, Attitudes And Approaches To Management species in cities. Geography 100, 144 (2015).

(Earthscan, 2012). 52. Gaertner, M. et al. Managing invasive species in cities: a framework from

16. Frawley, J. & McCalman, I. Rethinking Invasion Ecologies from the Environmental Cape Town, South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 151, 1–9 (2016).

Humanities (Routledge, 2014). 53. Comaroff, J. & Comaroff, J. L. Naturing the nation: aliens, apocalypse, and the

17. Castree, N. Making Sense of Nature (Routledge, 2013). postcolonial state. Social Ident. 7, 233–265 (2001).

18. Haraway, D. J. When Species Meet (Univ. Minnesota Press, 2008). 54. Ballard, R. & Jones, G. A. Natural neighbors: indigenous landscapes and eco-

19. Bennett, N. J. et al. Conservation social science: understanding and integrating estates in Durban, South Africa. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 101, 131–148 (2011).

human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 205, 93–108 (2017). 55. Carruthers, J. et al. A native at home and abroad: the history, politics, ethics and

20. Sandbrook, C., Adams, W. M., Büscher, B. & Vira, B. Social research and aesthetics of acacias. Divers. Distrib. 17, 810–821 (2011).

biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 27, 1487–1490 (2013). 56. Crosby, A. W. Ecological Imperialism (Past Present Soc., 1986).

21. Boivin, N. L. et al. Ecological consequences of human niche construction: 57. Robbins, P. & Moore, S. A. Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of

examining long-term anthropogenic shaping of global species distributions. the Anthropocene. Cult. Geogr. 20, 3–19 (2013).

Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 6388–6396 (2016). 58. Ginn, F. Extension, subversion, containment: eco-nationalism and (post)colonial

22. Ellis, E. C. et al. Used planet: a global history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA nature in Aotearoa New Zealand. Trans. Inst. British Geogr. 33, 335–353 (2008).

110, 7978–7985 (2013). 59. Martin, R. J. & Trigger, D. Negotiating belonging: plants, people, and indigeneity

23. Warren, C. R. Perspectives on the ‘alien’ versus ‘native’ species debate: a critique in northern Australia. J. Roy. Anthropol. Inst. 21, 276–295 (2015).

of concepts, language and practice. Prog. Human Geogr. 31, 427–446 (2007). 60. Frawley, J. Containing Queensland prickly pear: buffer zones, closer settlement,

24. Richardson, D., Pysek, P., Simberloff, D., Rejmánek, M. & Mader, A. whiteness. J. Austr. Studies 38, 139–156 (2014).

Biological invasions-the widening debate: a response to Charles Warren. 61. Kull, C. A., Tassin, J. & Carrière, S. M. Approaching invasive species in

Progr. Human Geogr. 32, 295 (2008). Madagascar. Madagascar Conserv. Dev. 9, 60–70 (2014).

25. Preston, C. D. The terms ‘native’ and ‘alien’—a biogeographical perspective. 62. Buckley, Y. M. & Han, Y. Managing the side effects of invasion control.

Progr. Human Geogr. 33, 702–711 (2009). Science 344, 975–976 (2014).

26. Warren, C. R. Using the native/alien classification for description not 63. Reed, M. & Curzon, R. Stakeholder mapping for the governance of biosecurity:

prescription: a response to Christopher Preston. Progr. Human Geogr. a literature review. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 12, 15–38 (2015).

33, 711–713 (2009). 64. Buijs, A. E. & Elands, B. H. Does expertise matter? An in-depth understanding

27. Simberloff, D. Nature, natives, nativism, and management. Environ. Ethics of people’s structure of thoughts on nature and its management implications.

34, 5–25 (2012). Biol. Conserv. 168, 184–191 (2013).

28. Davis, M. A. et al. Don’t judge species on their origins. Nature 65. Ernwein, M. & Fall, J. J. Communicating invasion: understanding social

474, 153–154 (2011). anxieties around mobile species. Geogr. Ann. 97, 155–167 (2015).

29. Simberloff, D. Non-natives: 141 scientists object. Nature 475, 36 (2011). 66. van Der Wal, R., Fischer, A., Selge, S. & Larson, B. M. Neither the public

30. Lockwood, J. L., Hoopes, M. F. & Marchetti, M. P. Non-natives: plusses of nor experts judge species primarily on their origins. Environ. Conserv.

invasion ecology. Nature 475, 36 (2011). 42, 349–355 (2015).

31. Colautti, R. I. & MacIsaac, H. J. A neutral terminology to define ‘invasive’ 67. Fischer, A., Selge, S., van der Wal, R. & Larson, B. M. The public and

species. Divers. Distrib. 10, 135–141 (2004). professionals reason similarly about the management of non-native invasive

32. Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D. M. Invasive species, environmental change and species: a quantitative investigation of the relationship between beliefs and

management, and health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Res. 35, 25–55 (2010). attitudes. PloS ONE 9, e105495 (2014).

33. Richardson, D. M., Pysek, P. & Carlton, J. T. in Fifty Years of Invasion 68. Young, A. M. & Larson, B. M. Clarifying debates in invasion biology: a survey of

Ecology: The Legacy of Charles Elton (ed. Richardson, D. M.) invasion biologists. Environ. Res. 111, 893–898 (2011).

409–420 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011). 69. Lundberg, A. Conflicts between perception and reality in the management

34. Fall, J. J. in Biosecurity: The Socio-Politics of Invasive Species and Infectious of alien species in forest ecosystems: a Norwegian case study. Landsc. Res.

Diseases (eds Dobson, A., Barker, K. & Taylor, S. L.) 167–181 (Routledge, 2014). 35, 319–338 (2010).

35. Tassin, J. & Kull, C. A. Facing the broader dimensions of biological invasions. 70. Hobbs, R. J. Grieving for the past and hoping for the future: balancing polarizing

Land Use Pol. 42, 165–169 (2015). perspectives in conservation and restoration. Restor. Ecol. 21, 145–148 (2013).

6 NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

NATURE PLANTS REVIEW ARTICLE

71. Bhattacharyya, J. & Larson, B. M. The need for indigenous voices in discourse 102. Genovesi, P. in Issues in Bioinvasion Science: EEI 2003: A Contribution to the

about introduced species: insights from a controversy over wild horses. Knowledge on Invasive Alien Species (eds Capdevila-Arguelles, L. & Zilletti, B.)

Environ. Values 23, 663–684 (2014). 127–133 (2005).

72. Trigger, D. S. Indigeneity, ferality, and what ‘belongs’ in the Australian bush: 103. Schmiedel, D. et al. Evaluation system for management measures of invasive

Aboriginal responses to ‘introduced’ animals and plants in a settler-descendant alien species. Biodivers. Conserv. 25, 357–374 (2016).

society. J. Roy. Anthrop. Inst. 14, 628–646 (2008). 104. Hulme, P. E., Pyšek, P., Nentwig, W. & Vilà, M. Will threat of biological

73. Vaarzon-Morel, P. Changes in Aboriginal perceptions of feral camels and of their invasions unite the European Union. Science 324, 40–41 (2009).

impacts and management. Rangeland J. 32, 73–85 (2010). 105. Olwig, K. R. Natives and aliens in the national landscape. Landsc. Res.

74. Head, L. & Atchison, J. Entangled and invasive lives: indigenous invasive plant 28, 61–74 (2003).

management in northern Australia. Geogr. Ann. 97, 169–182 (2015). 106. Liu, S. & Cook, D. Eradicate, contain, or live with it? Collaborating

75. Bach, T. & Larson, B. Speaking about weeds: indigenous elders’ metaphors for with stakeholders to evaluate responses to invasive species. Food Secur.

invasives and their management. Environ. Values (in the press). 8, 49–59 (2016).

76. Sharma, L. & Khandelwal, S. Weeds of Rajasthan and their ethno-botanical 107. Reed, M. S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management:

importance. Studies Ethno-Med. 4, 75–79 (2010). a literature review. Biol. Conserv. 141, 2417–2431 (2008).

77. Hall, S. J. Cultural disturbances and local ecological knowledge mediate 108. Touza, J., Pérez-Alonso, A., Chas-Amil, M. L. & Dehnen-Schmutz, K.

cattail (Typha domingensis) invasion in lake Pátzcuaro, México. Hum. Ecol. Explaining the rank order of invasive plants by stakeholder groups. Ecol. Econ.

37, 241–249 (2009). 105, 330–341 (2014).

78. Bart, D. & Simon, M. Evaluating local knowledge to develop integrative 109. García-Llorente, M., Martín-López, B., González, J. A., Alcorlo, P. & Montes, C.

invasive-species control strategies. Hum. Ecol. 41, 779–788 (2013). Social perceptions of the impacts and benefits of invasive alien species:

79. Jevon, T. & Shackleton, C. M. Integrating local knowledge and forest surveys to implications for management. Biol. Conserv. 141, 2969–2983 (2008).

assess Lantana camara impacts on indigenous species recruitment in Mazeppa 110. Shackleton, R. T., Le Maitre, D. C., van Wilgen, B. W. & Richardson, D. M.

Bay, South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 43, 247–254 (2015). Identifying barriers to effective management of widespread invasive alien trees:

80. Hu, R. & Gill, N. Movement of garden plants from market to bushland: Prosopis species (mesquite) in South Africa as a case study. Glob. Environ.

gardeners’ plant procurement and garden-related behaviour. Geogr. Res. Change 38, 183–194 (2016).

53, 134–144 (2015). 111. Brenner, J. C. Pasture conversion, private ranchers, and the invasive

81. Zagorski, T., Kirkpatrick, J. & Stratford, E. Gardens and the bush: exotic buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) in Mexico’s Sonoran Desert.

gardeners’ attitudes, garden types and invasives. Australian Geogr. Studies Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 101, 84–106 (2011).

42, 207–220 (2004). 112. Binimelis, R., Pengue, W. & Monterroso, I. “Transgenic treadmill”: responses to

82. Trigger, D. & Mulcock, J. Native vs exotic: cultural discourse about flora, fauna the emergence and spread of glyphosate-resistant johnsongrass in Argentina.

and belonging in Australia. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 84, 1301–1310 (2005). Geoforum 40, 623–633 (2009).

83. Qvenild, M., Setten, G. & Skår, M. Politicising plants: dwelling and invasive alien 113. Graham, S. Three cooperative pathways to solving a collective weed

species in domestic gardens in Norway. Norwegian J. Geogr. 68, 22–33 (2014). management problem. Australasian J. Environ. Manage. 20, 116–129 (2013).

84. Sjöholm, C. & Saltzman, K. in Nature, Time and Environmental 114. Atchison, J. Experiments in co-existence: the science and practices

Management: Scandinavian and Australian perspectives on peoples of biocontrol in invasive species management. Environ. Planning A

and landscapes (eds Head, L., Saltzman, K., Setten, G. & Stenseke, M.) 47, 1697–1712 (2015).

112–129 (Routledge, 2017). 115. Head, L. et al. Living with invasive plants in the Anthropocene: the importance

85. Barker, K. Flexible boundaries in biosecurity: accommodating gorse in Aotearoa of understanding practice and experience. Conserv. Soc. 13, 311 (2015).

New Zealand. Environ. Planning A 40, 1598–1614 (2008). 116. Hawthorne, T. L. et al. Mapping non-native invasive species and accessibility

86. Atchison, J. & Head, L. Eradicating bodies in invasive plant management. in an urban forest: a case study of participatory mapping and citizen science in

Environ. Planning D 31, 951–968 (2013). Atlanta, Georgia. Appl. Geogr. 56, 187–198 (2015).

87. Ryan, J. C. Botanical memory: exploring emotional recollections of native flora 117. Head, L. & Atchison, J. Governing invasive plants: policy and practice in

in the Southwest of Western Australia. Emotion Space Soc. 8, 27–38 (2013). managing the Gamba grass (Andropogon gayanus)–bushfire nexus in northern

88. Instone, L. Unruly grasses: affective attunements in the ecological restoration of Australia. Land Use Pol. 47, 225–234 (2015).

urban native grasslands in Australia. Emotion Space Soc. 10, 79–86 (2014). 118. Richardson, D. M. & Pyšek, P. Plant invasions: merging the concepts of species

89. Trudgill, S. A requiem for the British flora? Emotional biogeographies and invasiveness and community invasibility. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 30, 409–431 (2006).

environmental change. Area 40, 99–107 (2008). 119. Robbins, P. Comparing invasive networks: cultural and political biographies of

90. Hitchings, R. People, plants and performance: on actor network theory and the invasive species. Geogr. Rev. 94, 139–156 (2004).

material pleasures of the private garden. Social Cultur. Geogr. 4, 99–114 (2003). 120. Ogden, L. et al. Global assemblages, resilience, and Earth Stewardship in the

91. Power, E. R. Human–nature relations in suburban gardens. Australian Geogr. Anthropocene. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 341–347 (2013).

36, 39–53 (2005). 121. Hobbs, R. J. et al. Novel ecosystems: theoretical and management aspects of the

92. Doody, B. J., Perkins, H. C., Sullivan, J. J., Meurk, C. D. & Stewart, G. H. new ecological world order. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 15, 1–7 (2006).

Performing weeds: Gardening, plant agencies and urban plant conservation. 122. Ellis, E. C. & Ramankutty, N. Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes

Geoforum 56, 124–136 (2014). of the world. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 439–447 (2008).

93. Head, L., Atchison, J. & Phillips, C. The distinctive capacities of plants:

re-thinking difference via invasive species. Trans. Instit. British Geogr. Acknowledgements

40, 399–413 (2015). Funding was provided by the Australian Research Council (FL0992397). I am grateful to

94. Woods, M. & Moriarty, P. V. Strangers in a strange land: the problem of exotic many colleagues who have discussed these issues over the years, particularly J. Atchison,

species. Environ. Values 10, 163–191 (2001). N. Gill and D. Trigger. Thanks to T. Roberts and I. Aguirre-Bielschowsky for assistance

95. Kendle, A. D. & Rose, J. E. The aliens have landed! What are the justifications with literature searches.

for ‘native only’policies in landscape plantings? Landsc. Urban Planning

47, 19–31 (2000).

96. Godden, L., Nelson, R. & Peel, J. Controlling invasive species: managing Author contributions

risks to Australia’s agricultural sustainability and biodiversity protection. L.H. was responsible for all project design and planning, analysis of literature,

Australasian J. Environ. Manage. 13, 166–184 (2006). conceptualization and writing of the paper.

97. Beck, K. G. et al. Invasive species defined in a policy context: recommendations

from the Federal Invasive Species Advisory Committee. Invas. Plant Sci. Manage.

1, 414–421 (2008).

Additional information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

98. Maye, D., Dibden, J., Higgins, V. & Potter, C. Governing biosecurity in

a neoliberal world: comparative perspectives from Australia and the Correspondence should be addressed to L.H.

United Kingdom. Environ. Planning A 44, 150–168 (2012). How to cite this article: Head, L. The social dimensions of invasive plants. Nat. Plants

99. Clark, N. The demon-seed bioinvasion as the unsettling of environmental 3, 17075 (2017).

cosmopolitanism. Theory Cult. Soc. 19, 101–125 (2002). Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

100. Keller, R. P. & Perrings, C. International policy options for reducing the published maps and institutional affiliations.

environmental impacts of invasive species. BioScience 61, 1005–1012 (2011).

101. Barbier, E. B., Knowler, D., Gwatipedza, J., Reichard, S. H. & Hodges, A. R.

Implementing policies to control invasive plant species. BioScience Competing interests

63, 132–138 (2013). The author declares no competing financial interests.

NATURE PLANTS 3, 17075 (2017) | DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75 | www.nature.com/natureplants 7

©

2

0

1

7

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

You might also like

- Dunne, Tim, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith. International Relations Theories. Intro (13-33)Document24 pagesDunne, Tim, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith. International Relations Theories. Intro (13-33)Vanessa ParedesNo ratings yet

- Paul Smith - Discerning The SubjectDocument226 pagesPaul Smith - Discerning The SubjectdisconnectaNo ratings yet

- Exodus Post Apocalyptic PDF 10Document2 pagesExodus Post Apocalyptic PDF 10RushabhNo ratings yet

- EnvironmEntal Communication TheoriesDocument5 pagesEnvironmEntal Communication TheoriesDenisaNo ratings yet

- North American Indians - A Very Short IntroductionDocument147 pagesNorth American Indians - A Very Short IntroductionsiesmannNo ratings yet

- Larry Dossey - HealingBeyondtheBodyDocument2 pagesLarry Dossey - HealingBeyondtheBodypaulxeNo ratings yet

- Rhodes Solutions Ch4Document19 pagesRhodes Solutions Ch4Joson Chai100% (4)

- WR5 Weaver 2014 Social Science and Global ChangeDocument4 pagesWR5 Weaver 2014 Social Science and Global ChangemkberloniNo ratings yet

- Human Behaviour As A Long-Term Ecological Driver of Non-Human EvolutionDocument11 pagesHuman Behaviour As A Long-Term Ecological Driver of Non-Human EvolutionSantiago ToroNo ratings yet

- Should Social Science Be More Solution-Oriented?: PerspectiveDocument5 pagesShould Social Science Be More Solution-Oriented?: Perspectivelmary20074193No ratings yet

- Gam Feldt 2017Document7 pagesGam Feldt 2017claudiaNo ratings yet

- De-Extinction Costs, Benefits and Ethics PDFDocument2 pagesDe-Extinction Costs, Benefits and Ethics PDFOlariu AndreiNo ratings yet

- Comment: Global Standards For Stem-Cell ResearchDocument3 pagesComment: Global Standards For Stem-Cell ResearchDenySidiqMulyonoChtNo ratings yet

- The New Genetics of IntelligenceDocument12 pagesThe New Genetics of IntelligenceKasperiSoininenNo ratings yet

- Taxonomy AnarchyDocument3 pagesTaxonomy AnarchyRuth Yanina Valdez MisaraymeNo ratings yet

- Garnet & Christidis 2017Document3 pagesGarnet & Christidis 2017Gerard QuintosNo ratings yet

- Reboot For The AI Revolution: CommentDocument4 pagesReboot For The AI Revolution: CommentAaron YangNo ratings yet

- Interplay Between Defects, Disoroder and Flexibility in Metal-Organic Frameworks Prof CheethamDocument6 pagesInterplay Between Defects, Disoroder and Flexibility in Metal-Organic Frameworks Prof CheethamNguyen Dang Hoai DangNo ratings yet

- Reviews: The Increasing Dynamic, Functional Complexity of Bio-Interface MaterialsDocument15 pagesReviews: The Increasing Dynamic, Functional Complexity of Bio-Interface MaterialsGiggly HadidNo ratings yet

- Wing Ho Man (2017) Microbiota of The Respiratory Tract, Gatekeeper To Respiratory HealthDocument12 pagesWing Ho Man (2017) Microbiota of The Respiratory Tract, Gatekeeper To Respiratory HealthLuan DiasNo ratings yet

- 2017 HerendeenEtAL Angiosperms LectureFossilPlants PalynologyDocument8 pages2017 HerendeenEtAL Angiosperms LectureFossilPlants PalynologyJavier PautaNo ratings yet

- Engineering The Microbiome: OutlookDocument3 pagesEngineering The Microbiome: OutlookLindo PulgosoNo ratings yet

- The School ExperimentDocument4 pagesThe School ExperimentscribbogNo ratings yet

- 1 ISAPP Consensus Statement PREBIOTICS 2017Document12 pages1 ISAPP Consensus Statement PREBIOTICS 2017KatherineNo ratings yet

- 10 1038@nrurol 2018 1Document15 pages10 1038@nrurol 2018 1cristianNo ratings yet

- Dental Care in Modern Art (1914-2014)Document6 pagesDental Care in Modern Art (1914-2014)Sara Omar MustafaNo ratings yet

- All ChaptersDocument33 pagesAll Chaptersq24rzsxbr8No ratings yet

- Hall2023 mentalHealthCrisisScienceDocument3 pagesHall2023 mentalHealthCrisisScienceSBNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Geography: Jinat Hossain, Farhana RafiqDocument14 pagesIntroduction To Geography: Jinat Hossain, Farhana RafiqAshek AHmedNo ratings yet

- The Hunt For A Healthy Microbiome: OutlookDocument3 pagesThe Hunt For A Healthy Microbiome: OutlookLindo PulgosoNo ratings yet

- History: Pharmaceutical Engineering Is A Branch ofDocument7 pagesHistory: Pharmaceutical Engineering Is A Branch ofJonahNo ratings yet

- News in Focus: Giant Health Studies Try To Tap Wearable ElectronicsDocument2 pagesNews in Focus: Giant Health Studies Try To Tap Wearable ElectronicsLuiz Folha FlaskNo ratings yet

- d41586-020-00837-4Document3 pagesd41586-020-00837-4Thiago SartiNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Broadband: Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument3 pagesBacterial Broadband: Irritable Bowel SyndromeMedical_DoctorNo ratings yet

- Loss-Of-Function Genetic Tools For Animal Models - Cross-Species and Cross-Platform DifferencesDocument17 pagesLoss-Of-Function Genetic Tools For Animal Models - Cross-Species and Cross-Platform DifferencesLeon PalomeraNo ratings yet

- Food System PrioritiesDocument3 pagesFood System Prioritiesbubursedap jbNo ratings yet

- 1976 REVIEW ON Cross-Cultural Universale of Affective MeaningDocument2 pages1976 REVIEW ON Cross-Cultural Universale of Affective MeaningCesar Cisneros PueblaNo ratings yet

- The Ecosystem Concept in Natural Resource ManagementFrom EverandThe Ecosystem Concept in Natural Resource ManagementGeorge Van DyneNo ratings yet

- The Power of Diversity.Document4 pagesThe Power of Diversity.Jonas JacobsenNo ratings yet

- Unexplored Therapeutic Opportunities in The Human GenomeDocument16 pagesUnexplored Therapeutic Opportunities in The Human GenomeTony ChengNo ratings yet

- Reeves, Et Al., Nature, Jan 16, 2020.Document4 pagesReeves, Et Al., Nature, Jan 16, 2020.Roxanne ReevesNo ratings yet

- Research Round-Up: OutlookDocument2 pagesResearch Round-Up: OutlookLindo PulgosoNo ratings yet

- Van Der Aa and Blommaert 2015 EthnoDocument13 pagesVan Der Aa and Blommaert 2015 EthnoQfwfQ01No ratings yet

- No Publication Without ConfirmationDocument3 pagesNo Publication Without ConfirmationRuben Gutierrez-ArizacaNo ratings yet

- King Keohane Verba Designing Social InquiryDocument45 pagesKing Keohane Verba Designing Social InquiryRominaLara100% (1)

- Engineering and Physical Sciences in Oncology - Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument17 pagesEngineering and Physical Sciences in Oncology - Challenges and OpportunitiesAlessandroNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of Membrane Organization Composition, Regulation and Roles of Lipid RaftsDocument14 pagesThe Mystery of Membrane Organization Composition, Regulation and Roles of Lipid RaftsByanka TouilleNo ratings yet

- Energy Research & Social ScienceDocument8 pagesEnergy Research & Social ScienceSoporte CeffanNo ratings yet

- The Quest For An All-Inclusive Human GenomeDocument4 pagesThe Quest For An All-Inclusive Human GenomeAnahí TessaNo ratings yet

- Integration Site Selection by Retroviruses and Transposable Elements in EukaryotesDocument17 pagesIntegration Site Selection by Retroviruses and Transposable Elements in EukaryotesLuis ZabalaNo ratings yet

- BlumerDocument111 pagesBlumerLaloBytesNo ratings yet

- Atomic Force Microscopy - Based Characterization and Design of BiointerfacesDocument16 pagesAtomic Force Microscopy - Based Characterization and Design of BiointerfacesAngel LopezNo ratings yet

- Part Three Organisation and Cooperation in International Comparative ResearchDocument40 pagesPart Three Organisation and Cooperation in International Comparative ResearchPablo SantibañezNo ratings yet

- Research ProblemDocument11 pagesResearch ProblemerwanramliNo ratings yet

- AguaInterdisciplinariedad ConnellyDocument9 pagesAguaInterdisciplinariedad ConnellyDiego SanvicensNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Approaches To Human EcologyDocument24 pagesConceptual Approaches To Human EcologyBilly WenNo ratings yet

- Study The Survivors: This WeekDocument1 pageStudy The Survivors: This WeeknomadNo ratings yet

- Nature 2017 21508Document2 pagesNature 2017 21508sharick.aristizabalNo ratings yet

- Villalobos NatureOfSociologicalTheoryDocument3 pagesVillalobos NatureOfSociologicalTheoryJoshua Ofiasa Villalobos HLNo ratings yet

- Summary of Ecological AnthropologyDocument2 pagesSummary of Ecological AnthropologyZhidden Ethiopian RevolutionistNo ratings yet

- The Greatest Hits of The Human GenomeDocument5 pagesThe Greatest Hits of The Human GenomeIngri CastilloNo ratings yet

- Big Brain, Big DataDocument3 pagesBig Brain, Big DataDejan Chandra GopeNo ratings yet

- Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation MIH - An OverviewDocument9 pagesMolar Incisor Hypomineralisation MIH - An OverviewBabaNo ratings yet

- Introducing The Nanoworld: Nature Nanotechnology August 2017Document2 pagesIntroducing The Nanoworld: Nature Nanotechnology August 2017KG AgramonNo ratings yet

- 30 Third Generation of Sociology of AgeingDocument17 pages30 Third Generation of Sociology of AgeinggiacomobarnigeoNo ratings yet

- Class 7 CitationDocument9 pagesClass 7 Citationapi-3697538No ratings yet

- Biodiversity Classification GuideDocument32 pagesBiodiversity Classification GuideSasikumar Kovalan100% (3)

- Ass 3 MGT206 11.9.2020Document2 pagesAss 3 MGT206 11.9.2020Ashiqur RahmanNo ratings yet

- The Way To Sell: Powered byDocument25 pagesThe Way To Sell: Powered bysagarsononiNo ratings yet

- SLE On TeamworkDocument9 pagesSLE On TeamworkAquino Samuel Jr.No ratings yet

- Contribution Sushruta AnatomyDocument5 pagesContribution Sushruta AnatomyEmmanuelle Soni-DessaigneNo ratings yet

- PbisDocument36 pagesPbisapi-257903405No ratings yet

- Converting Units of Measure PDFDocument23 pagesConverting Units of Measure PDFM Faisal ChNo ratings yet

- Edu 510 Final ProjectDocument13 pagesEdu 510 Final Projectapi-324235159No ratings yet

- BS 476-7-1997Document24 pagesBS 476-7-1997Ivan ChanNo ratings yet

- Evidence Law PDFDocument15 pagesEvidence Law PDFwanborNo ratings yet

- Khin Thandar Myint EMPADocument101 pagesKhin Thandar Myint EMPAAshin NandavamsaNo ratings yet

- Cps InfographicDocument1 pageCps Infographicapi-665846419No ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science 10Document7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Science 10Glen MillarNo ratings yet

- John R. Van Wazer's concise overview of phosphorus compound nomenclatureDocument7 pagesJohn R. Van Wazer's concise overview of phosphorus compound nomenclatureFernanda Stuani PereiraNo ratings yet

- Journal EntriesDocument10 pagesJournal Entriesapi-283322366No ratings yet

- New GK PDFDocument3 pagesNew GK PDFkbkwebsNo ratings yet

- Sons and Lovers AuthorDocument9 pagesSons and Lovers AuthorArmen NeziriNo ratings yet

- Reducing Healthcare Workers' InjuriesDocument24 pagesReducing Healthcare Workers' InjuriesAnaNo ratings yet

- Edwards 1999 Emotion DiscourseDocument22 pagesEdwards 1999 Emotion DiscourseRebeca CenaNo ratings yet

- Williams-In Excess of EpistemologyDocument19 pagesWilliams-In Excess of EpistemologyJesúsNo ratings yet

- CV Jan 2015 SDocument4 pagesCV Jan 2015 Sapi-276142935No ratings yet

- Personal Branding dan Positioning Mempengaruhi Perilaku Pemilih di Kabupaten Bone BolangoDocument17 pagesPersonal Branding dan Positioning Mempengaruhi Perilaku Pemilih di Kabupaten Bone BolangoMuhammad Irfan BasriNo ratings yet

- 04-DDD.Assignment 2 frontsheet 2018-2019-đã chuyển đổi PDFDocument21 pages04-DDD.Assignment 2 frontsheet 2018-2019-đã chuyển đổi PDFl1111c1anh-5No ratings yet

- Ardipithecus Ramidus Is A Hominin Species Dating To Between 4.5 and 4.2 Million Years AgoDocument5 pagesArdipithecus Ramidus Is A Hominin Species Dating To Between 4.5 and 4.2 Million Years AgoBianca IrimieNo ratings yet