Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Moby Grape BAM Magazine 1977

Uploaded by

auweia1Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Moby Grape BAM Magazine 1977

Uploaded by

auweia1Copyright:

Available Formats

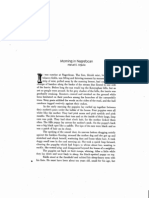

24 BAM Magazine/November 1977

MOBY GRAPE

Still Crazed After All These Years

By Clark Peterson

The song ended, but the malady lingered on. There was guitarist Alexander “Skip” Spence, stage

right at the Old Waldorf on September 26, convulsed in a blissful euphoria. Only a few seconds

later he was completely deadpan – from manic to depressive in the time it takes to say, “Moby

Grape lives!” While Peter Lewis attempted to sing a soft ballad at stage right, Spence mumbled

incoherently into his mike. Well, I guess one man’s distraction is another man’s comic relief.

It doesn’t take any special insight to see that the latest incarnation of Moby Grape, the

legendary San Francisco band that first popularized the three-guitar style, has gone through the

proverbial hard times. While many people (including myself and Mink DeVille’s Willy DeVille)

steadfastly believe that they are still the best rock band to ever come out of California and that their

sensational first album is a classic, they slipped dramatically with each of their four successive

albums. Today, three original members – Spence (31), Lewis (32), and Jerry Miller (34) – have the

unmistakable appearance of having more ZigZag papers between their fingertips than guitar picks.

“Is that what I spy – a binky? My life for a binky!” gasps Peter Lewis, ogling a joint. We

are slumped on hotel beds at the Holiday Lodge in S.F. The atmosphere is high school locker room.

Such words as “ya know” I “man” and “together” are bandied about, though the overriding

impression is another word that comes up often in their conversation: “crazy.” Though bassist

Christian “Skeeter” Powell and drummer Fuzzy John are mild-mannered musicians who watch this

bull session with bemusement, Spence regularly breaks into hysterics.

“A flying saucer lands at the White House, asks President Ford for a cup of sugar!” He

bubbles over like a foamy soda fountain Coke, interrupting the conversation he’s been carrying on

with himself. The other guys join in the raucous laughter and then return to their binkies –

something that caused them trouble years ago.

Back in the Summer of Love, Moby Grape was an exhilarating act. Their label, Columbia,

organized a coming-out performance for them at the old Avalon Ballroom complete with Moby

Grape wine distributed free in their own bottles and 10,000 orchids from radio station promotion.

After the show, the band repaired to Marin County, where they were arrested for possession of

marijuana and contributing to the delinquency of minors.

“It was a frame-up,” Miller remembers painfully. “There was no marijuana involved – just

politics.” The bust hurt their careers and contributed to their decline.

Walked into the courtroom

Knowing this was going to bring me down.

The big, fat, bald

Representative of Justice

And the prosecutor began to frown.

I said, “I’m sorry for the things I’ve done,

And I’m sure to change my ways.”

The judge looked down at me and said,

“For getting smart, boy,

I’m going to give you more than a lifetime.”

I’ve got murder in my heart for the judge.

From “Murder in my Heart for the Judge” by Don Stevenson, © 1968 Moby Grape Music (BMI)

A few days after the Holiday Lodge interview, publisher/editor Dennis Erokan,

photographer Dave Patrick, and I drive the weaving trek to Boulder Creek to interview the three

founding Grapes at Jerry Miller’s house. After a lip-smacking lunch at the Catalyst in Santa Cruz,

where people gazed at the eclipse while the three of us gazed at the gorgeous native women, we

finished the last leg of our journey.

Miller lives on top of a tree-covered hill so secluded that we joke about finding a platoon of

Beaver Patrol scouts to navigate for us. Upon arriving, Miller shows us his downstairs rehearsal

room where Lewis (son of actress Loretta Young – for what it’s worth) temporarily lives, the

surrounding woods, and the upstairs where most of the interview is to take place. As Spence, who

lives down the hill, talks by himself a few feet away, Miller and Lewis reflect on the band’s rough

days. When asked why Spence left the group during the New York recording sessions for their

second album, WOW, the twosome flash worried looks at each other, pause, and then Miller speaks.

“That New York trip must have put him through the ringer,” he begins, briefly switching to

a semi-Swedish brogue. “You take the Albert Hotel with your cock-a roaches in there and your

doorman selling heroin and fire drills at three in the morning. You work from noon until 4 a.m. and

then go back to that dumb hotel and tap your foot until they’re waking you up with the phone to go

back to the studio. Pretty soon you get cross-eyed and crazy, and the smog gets to ya. It was the

lowest level of living imaginable. It was stupid for us to be paying $150 an hour to record and live

in that piece of shit. Our minds were nowhere; we weren’t elevated or anything. You have to keep

clean and go where it’s not funky and there’s no rats and you can breathe. Our mistake was

allowing ourselves to be fucked around to that extreme. Otherwise we’d have been okay.”

Spence, reported to have been in mental institutions after serious drug abuse in the years

following the Grape break-up, made an immediate impression on Miller when they first met in the

‘60’s: “Skip was so crazed, I thought, ‘What’s he going to do, beat tambourines?’ But when he

came to the gig, he had a guitar and I went, ‘Whew, three guitars!’”

John Chesleigh, the band’s present manager, attempts to shed some light on Spence’s

enigmatic behavior. “At one point, Skip was laid out on a slab at the morgue and had been

pronounced dead; and then he sat up,” Chesleigh maintains. “There’s no doubt about it: he’s spaced

out. He has brain-cell damage from when he ‘died.’ His heart had stopped and the air to his brain

had stopped. As far as everything else goes, he’s totally together. “ Chesleigh later said that Spence

would sometimes sit out the last set of a three-set date, and was the first to start destroying amps

onstage.

Before joining Moby Grape, Spence was the Jefferson Airplane’s drummer on their first

album. It was through the Airplane’s manager, Matthew Katz (rhymes with “gates”), that Spence

met the other four Grapes. Lewis tells the story:

“I had a band called Peter & the Wolves with Bob Neukirk on drums,” Lewis relates.

“Neukirk joined up with Joel Scott Hill and Bob Mosley, replacing Johnny Barbata [now with the

Starship] on drums. The group folded, so Joel and I decided to try it together. I asked Joel who we

should get for bass and he said, ‘I know this guy Bob Mosley, but he’s crazy.’ I said, ‘Well, who

cares?’ so we called Mosley down to L.A.

“He was playing in bars in Gilroy,” Lewis continues “He comes to L.A. with these dark

glasses on and his hair all razor-cut. His hair used to be down to his ass, so I figured he must have

gone through some changes. I thought, ‘This guy is crazy.’”

The threesome played one night with another drummer, then got a call from Bob Neukirk

saying that Matthew Katz wanted to form a band with Neukirk, Hill, Mosley, and Lewis.

“Joel didn’t want to do it because he thought Matthew was crazy,” Lewis says, resuming his

tale. “So it ended up being the three of us. We came to Frisco and met Skippy and played together

and then decided the drummer wasn’t makin’ it. Mosley said, ‘I know this guy Jerry Miller, and

Don Stevenson’ – who I heard was fuckin’ great – ‘but -they only work together.’ I said, ‘Great,

let’s get ‘em.’ That’s how the group started. No ego trips.” Soon after, the band played in the film,

“The Sweet Ride.”

Though Katz started it all rolling, he also wanted to call a halt to it due to a legal wrangle

over the name. (Katz ended his involvement with the band early in their career, but claimed he still

had legal ownership of their title.) In 1973 when the group played under the name Moby Grape

(with originals Jerry Miller, Peter Lewis, and Bob Mosley, and newcomers Johnny C. and Jeff

Blackburn), one of their gigs was a Sounds of the City show at Winterland. The booking was Bill

Graham’s way of giving local groups a chance at the big stage on Tuesday nights for reduced ticket

prices. The Grape canceled. The official reason was the Mosley had to return to the marine

reserves.

Miller: “Matthew Katz was therewith an injunction to stop us from playing as Moby Grape,

if it every got that far. He didn’t know we had canceled. We were through the week before with the

Starwood [L.A.) gig and weren’t going to do the Winterland gig no matter what. I got a letter from

New York saying the big local union wants union dues from the gig, and I never even played it.”

This was the third time Moby Grape had dissolved. The first time things began failing apart

was during the already mentioned WOW sessions. The members feel that David Rubinson, who

produced all but their Truly Fine Citizen album, had rushed them and even rained one song, “Bitter

Wind.” The song begins as a beautiful, moody ballad, but like too many songs recorded in the late

‘60’s (even Johnny Rivers fell victim), it contains a “psychedelic” passage. The spine-tingling

harmony and Mosley’s soulful booming voice deteriorate into a cacophonous melange.

Lewis: “That was not our idea. It’s pretty much supposed to be folk-rock, but the producer

[Rubinson] did all of that after we finished recording it and were satisfied. It was beautiful before

that.”

The album featured another gimmick (this time a positive one) Rubinson thought up – a

78-rpm track. Written by Spence and introduced by Arthur Godfrey (who was found recording in

the adjacent studio), the song is a humorous, authentic-sounding period piece, circa 1940. “Just

Like Gene Autrey: A Foxtrot,” however, was not the only gimmick on the double disc. Two other

Spence compositions included a crashing motorcycle and a speeded-up Chipmunk-type vocal. The

other half of the album was a solid, bluesy jam with Al Kooper and Michael Bloomfield.

Moby Grape’s third album, ‘69, found that Spence had left, although one of his songs

recorded in New York, “Seeing,” was included. Rubinson’s liner notes talk of how the group “lost

all faith in themselves and stopped loving their music, stopped respecting each other,” and how

now they were starting all over with as fresh outlook.

“The back of that album cover is all bullshit,” Miller says, venting his anger. “As far as

saying we weren’t together for so long is true, but to say we were together then – we weren’t at all.

There’s never been any change, really. The album was recorded in sections. Me and Pete and Skip

would come in, and then Bob would do some and we’d be together. But it wasn’t together. We

weren’t communicating as people. We weren’t a band. Actually, it never has been flowing together

in the normal sense of the word. It always has been just a shade on the crazed side – the managerial

end of it – or if not, we would take the bull by the horns and fuck it up.”

After ‘69, which contained the sumptuous “It’s a Beautiful Day Today” by Mosley (who

was the next member to quit), the three remaining members recorded Truly Fine Citizen.

“I don’t like much from that album,” Miller concedes. “It was done in three days in

Nashville. There was only me and Peter and Donald with this bass player, Bob Moore, that Bob

Johnson [the producer] found. There wasn’t enough time to do good songs and the producer was a

joke-teller – that’s all.”

Before the band made this Nashville trip, Spence was there recording his own album, Oar,

on which he played all the instruments. In between relapses, Skip expands on his own history:

“It was recorded on an old three-track machine in 1968,” he says of Oar. “Now the album is

a cult item. Someone has 82 copies left in the City and it’s starting to come back.” Seven hundred

copies were sold worldwide.

Spence will not (or cannot) talk much about his days with the Airplane and recording on

their first album. “When I first started with them,” he says, “I couldn’t play worth shit. I learned

everything from this band. I learned drums in ‘65 when Marty Balin asked me to play. I met him at

the Shelter, in San Jose. It’s a folk music club. . .” Spence then starts laughing uncontrollably.

When he ceases, he continues.

“I met Marty at the Chateau Liberte,” he says, changing his story. “I met [the guys in Moby

Grape] later, but then again, there’s been another space going on that I can’t explain.”

In 1971, the original Grape regrouped and recorded 20 Granite Creek, their first album for

Warner Bros. (The title comes from the house address where it was recorded near Santa Cruz.) “We

finished the damn thing off at Pacific,” Miller spits, “which is dog meat.”

Not much was heard from the band until 1973 when they briefly reformed with Lewis,

Miller, and Mosley, and played the Bay Area. There was little magic on their opening night show at

the Great American Music Hall as Mosley spent the evening with his eyes on his shoes. “Well, he’s

got some great shoes,” cracks present Grape manager Chesleigh, who is quite a wit. (When asked

why the band keeps disbanding, Chesleigh quipped, “They’re just a bunch of disbandits.”

Mosley, who should have been brimming over with confidence, struck up another pose

altogether. “He was shy,” Lewis confides. “Sometimes he wouldn’t sing onstage because he’d get

uptight at himself.” Mosley ended up joining the Marines when he got his draft notice, and was

discharged after a fight. He’s been seen this summer playing in Santa Cruz with the Ducks (Neil

Young, Jeff Blackburn, and Johnny C), after turning down an offer to rejoin Moby Grape. (Mosley

has a house and family in San Diego where he spends most of his time.)

When Bill Graham was asked last year if he thought the Grape would ever come back, he

responded, “I hope not. Invariably they get together for the wrong reasons. I was involved with

them reuniting once, and it cost me.”

The band got together this past July. “Jerry called me in Ojai [near Santa Barbara],” Lewis

remembers vividly. “I was rooting up weeds in the garden and heard the phone, and I knew it was

Jerry so I just kept walking. I knew he’d keep ringing. He said, ‘Things are exciting, man. Better

get up here.’ I said, ‘Okay, tomorrow?’ And he said, ‘Right on..’” The excitement was Neil Young,

the Ducks and the crowds they were attracting to Santa Cruz. The Grape took advantage of it.

“Fuckin’ A, man!” Miller exclaims, enthusiastic over the impact the Grape has been having.

“This fuckin’ band’s got more fuckin’ work no matter what the hell the deal is, ya know? With any

artistry you put together, you usually have to fight and fight to get yourselves a draw. It’s weird.”

Time will tell if the 1977 Moby Grape will remain together – both as a group and in the

cliched sense. They say they are each free to go off as Miller has done before (for example, to

perform with Mike Finnegan). When asked if they have to keep the band going to prove to record

companies that they can last, they demur. Though on the one hand they are excited, on the other

they call this resurrection “no big deal.”

The Grape’s comeback was made possible when another band, the Original Haze, folded

and left Miller and Corny Bumpus (the Grape’s flute, sax, and organ man) free. Says Miller, “The

Haze was good, but it became impossible to finance an eight-piece band without a draw.” Miller

played lead guitar for the Haze for several years and previously had joined with Bill Champlin and

Fuzzy John in the Rhythm Dukes, not to mention playing with Fuzzy John and Mike Finnegan as a

trio. He believes it was his guitar work used on the Bobby Fuller Four’s classic “I Fought the Law

and the Law Won.”

In the late ‘60s, Miller would use two Marshall and two Bassman amps for his 1961 Gibson

L-5. He now wishes he had used less.

“We played the Fillmore East, but we didn’t know how much more the PA systems were

together than when we had last played there,” he remembers of a Grape concert. “We had all kinds

of totally unnecessary equipment, and then B.B. King came on after us with this little amp so tasty

and fine it picked up every note. I said, ‘Hey, let us do that again!’”

Their drummer, Don Stevenson, who now lives in Seattle, couldn’t handle the decibel level

back then. “Donald went to Frustration City,” Miller continues. “We should have cut back a bit, but

we got locked into the vibe of the time and tried to get all this power together. He’d finish by

kicking his drums off the stage.

Stevenson was portrayed as a bad boy on their first album cover, photographed by Jim

Marshall at the Junktique store in Fairfax. His middle finger, bared in the familiar gesture of

contempt, was soon enough erased to make the cover palatable to Middle America. The original

copies are collector’s items. “Someone might look at that finger and have a heart attack and die,”

laughs Miller, bringing to mind the stuffy character Margaret Dumont played in Marx Brothers

films.

The Grape all look back on that debut album as their best, despite the technically hazy

quality of the group vocals. “Our intention was three-guitar vocal harmony,” Miller explains.

“We’d figure we’d take each other’s regular songs and make gems out of ‘em, which is what we

did.” A large part of the songs’ appeal was the intricate guitar passages – each guitar going its own

way and yet flowing smoothly.

“We knew about that in the beginning,” Lewis comments, “and that’s why we wanted to

play. We were hep to that – that was keeno.” Now he looks back and sees all their trials and

tribulations that followed.

“I talked to the Eagles,” he sighs, “and they said we were responsible for good things that

happened to them. They learned from our mistakes. Now it’s the best it’s ever been for me as far as

material and attitudes and energy. Everyone’s a little older and more cooperative and less

egocentric.”

In performance, the Grape are still as uneven as they’ve always been. When they’re not

dazzling and creating an enormous energy, they can be ragged (singing off-key, starting and

stopping separately) and sloppy (lunging for the mike when caught off-guard). When Lewis, who

sings and writes engaging songs, was given a chance to solo on guitar at the Old Waldorf, he

produced notes that made the crowd wince. Their freewheeling, loose personalities make for

likewise performances. And with Spence’s antics, they can be embarrassing.

What saves Moby Grape are those thrilling moments when Miller’s fingers thrash up and

down his fretboard in a guitar frenzy, or when Lewis sings one of his pretty, melodic compositions.

And with Corny Bumpus injecting several additional instruments into the Grape’s guitar-based

sound, the band has a plethora of styles to draw on. Even with this diversity, they do not quarrel

over material as they used to. It’s not allowed. Though the Byrds, one of their heaviest influences

(and also newly reformed) were notorious for in-fighting, Moby Grape would sooner collapse from

a marijuana-induced awkwardness.

“If you get toasted enough, everything sounds good,” Miller smiles, dragging on a binky.

“You get up onstage and you feel fine as frog fuzz.” END

Rubinson Remembers Grape

David Rubinson, San Francisco’s famous re cord producer, discovered Moby Grape playing

with Quicksilver and Big Brother & the Holding Company many years ago, in San Francisco. He

wanted to sign all three to Columbia, but the label told him to pick one; he chose Moby Grape.

Reached for comment, Rubinson had this to say:

“I put my job on the line for them. There was no such thing as rock and roll in 1967 at CBS.

The Byrds and Paul Revere & the Raiders – that was it. When I brought the Grape in, they signed

for five grand. I took them away from Elektra and Atlantic, who had money in the bank in escrow. I

flew execs from CBS out here at my expense. I believed in them very, very, very much, but the

only thing I’ve reaped from it all is great disappointment.

“I thought then and still think they were the best American rock and roll band ever put

together. Peter Lewis is one of the great song writers America ever produced, and Jerry Miller is

one of the great guitar players ... there’s no reason why they haven’t reached a higher level of

success. Don Stevenson finally picked up his sticks and went back to Seattle and has some store.

Nice fella. Skip Spence is literally a genius. He sees the truth in everything. I guess that was

difficult for him to cope with. And Bob Mosley is easily the best rock and roll bass player I ever

heard, with more power and strength than any when he was on, and clearly a great, great, great,

white blues singer with a marvelous presence onstage. Obviously, this is a phenomenally talented

group of people, and they can blame other people if they wish for never living up to their potential

but the truth is that they found ways to lose. Consistently, whenever they could make a choice, they

constantly made the choice which would allow them to lose.

“We went back to New York [in 1971, when the band decided to reform again]. They sold

out the Fillmore East three nights. People were screaming for tickets, and Spence refused to get on

the plane to come and play. Then we came to the Fillmore West and did great business, and Mosley

refused to go on. Obviously it was a group of self-destructive, brilliantly talented people, and it’s

too bad because they were the closest thing America has produced to the Rolling Stones. It’s a

tragedy to me.

“As for me ruining ‘Bitter Wind,’ Mosley heard a tape put up in error by a CBS engineer,

was knocked out by it, and insisted a piece of tape go in backwards. We had a giant disagreement

about that – I hated it. The other guys were there when that happened in L.A., where WOW was

also done. It was during their overblown Sgt. Pepper period.

“About the 78-rpm song on WOW, everybody was taking all this shit too seriously. There

were people who had put bands together, basically, to give everybody a good time, and here were

these records being torn to pieces and microscopically investigated by so-called music critics –

something that still goes on. They were picking apart all the notes, and who sang what, and what

does this mean cosmically, and so forth, so we wanted some humor. In looking back, I wish I’d

done more of that.

“Concerning the liner notes on ‘69, they approved them as I read them on the phone. They

were very moved and thought it was the absolute truth, and it still appears to me to be the absolute

truth.

“Finally, about Matthew and me taking all their money, neither of us got rich from them.

They generally earned about one-third of what they think they earned. They signed publishing

agreements and signed things away. About two years ago I got them all together. We couldn’t put a

record out because Matthew Katz owned ¾ of this and ½ of that, and somebody at South Star

Music owned ¾ of this, and so forth. My object was to get them as much money as possible ... I

lent them $40,000-$50,000 when I was recording 20 Granite Creek, paying them salaries every

week whether they worked or not, on the basis that I would audit CBS and figure out who had

gotten how much and was owed how much and make a deal with Matthew Katz. It came to 200

pages of documents. We delivered all this information to them and as was typical, they couldn’t

agree on who would get paid what. Then the government came in with a tax lien and held up any

royalties. Because of this lien on their income, I’d hesitate to say what would happen if they had a

hit record tomorrow.”

Would Rubinson produce another Grape LP? “NO!” Will the Grape continue their pattern

of disbanding and reforming every few years? “That’s too depressing to think about.” –Clark

Peterson

You might also like

- First KISS: My 40-Year Obsession with the Hottest Band in the WorldFrom EverandFirst KISS: My 40-Year Obsession with the Hottest Band in the WorldRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Bing and Billie and Frank and Ella and Judy and BarbraFrom EverandBing and Billie and Frank and Ella and Judy and BarbraRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Everybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in 1960s Los AngelesFrom EverandEverybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in 1960s Los AngelesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- LIFE Gone Too Soon: The 27 Club - Rock Icons Who Died Too SoonFrom EverandLIFE Gone Too Soon: The 27 Club - Rock Icons Who Died Too SoonNo ratings yet

- Dreams Are Unfinished Thoughts: When a Fan Befriends a Drug-Addicted Rock StarFrom EverandDreams Are Unfinished Thoughts: When a Fan Befriends a Drug-Addicted Rock StarRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- We Never Knew Just What It Was ... The Story of the Chad Mitchell TrioFrom EverandWe Never Knew Just What It Was ... The Story of the Chad Mitchell TrioNo ratings yet

- Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music's HometownFrom EverandMemphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music's HometownNo ratings yet

- Driving to the Darkness: Splinter's Journey Through the 1960'SFrom EverandDriving to the Darkness: Splinter's Journey Through the 1960'SNo ratings yet

- Colin FlooksDocument6 pagesColin FlooksMatheus HerculanoNo ratings yet

- Boss: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band—The Illustrated HistoryFrom EverandBoss: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band—The Illustrated HistoryNo ratings yet

- All I Want Is Loving You: Popular Female Singers of the 1950sFrom EverandAll I Want Is Loving You: Popular Female Singers of the 1950sNo ratings yet

- Scuse Me While I Whip This Out: Reflections on Country Singers, Presidents, and Other TroublemakersFrom EverandScuse Me While I Whip This Out: Reflections on Country Singers, Presidents, and Other TroublemakersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (11)

- Redemption Song: The Ballad of Joe StrummerFrom EverandRedemption Song: The Ballad of Joe StrummerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (53)

- Runaway Dream: Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen's American VisionFrom EverandRunaway Dream: Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen's American VisionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- A Tribute To Jackie LevenDocument11 pagesA Tribute To Jackie LevenJohn CrowtherNo ratings yet

- Johnny's Jukebox Trivia: 1,001 Fantastic Questions from the Golden Age of Rock and RollFrom EverandJohnny's Jukebox Trivia: 1,001 Fantastic Questions from the Golden Age of Rock and RollNo ratings yet

- Your Song Changed My Life: From Jimmy Page to St. Vincent, Smokey Robinson to Hozier, Thirty-Five Beloved Artists on Their Journey and the Music That Inspired ItFrom EverandYour Song Changed My Life: From Jimmy Page to St. Vincent, Smokey Robinson to Hozier, Thirty-Five Beloved Artists on Their Journey and the Music That Inspired ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- Sun Sessions PDFDocument4 pagesSun Sessions PDFandi adnanNo ratings yet

- What a Difference a Day Makes: Women Who Conquered 1950s MusicFrom EverandWhat a Difference a Day Makes: Women Who Conquered 1950s MusicNo ratings yet

- Louisville Jug Music: From Earl McDonald to the National JubileeFrom EverandLouisville Jug Music: From Earl McDonald to the National JubileeNo ratings yet

- The Complete History of Black Sabbath: What Evil LurksFrom EverandThe Complete History of Black Sabbath: What Evil LurksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Springsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and EncountersFrom EverandSpringsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and EncountersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Rock 'n' Roll Archives, Volume Five: Rockin' 'round the WorldFrom EverandThe Rock 'n' Roll Archives, Volume Five: Rockin' 'round the WorldNo ratings yet

- Classic Magnolia Rock: History of Original Mississippi Rock and Roll 1953-1970From EverandClassic Magnolia Rock: History of Original Mississippi Rock and Roll 1953-1970No ratings yet

- Jimmy Cobb: The Reluctant Don: by Ashley Kahn - Nov 01 '03Document5 pagesJimmy Cobb: The Reluctant Don: by Ashley Kahn - Nov 01 '03Sebastian Corrinth100% (2)

- THE LORE OF THE DOORS: Celebrating Santa Barbara Connections As Legendary Rockers Mark MilestoneDocument6 pagesTHE LORE OF THE DOORS: Celebrating Santa Barbara Connections As Legendary Rockers Mark Milestonedelaware11No ratings yet

- Uncut 2016-04Document124 pagesUncut 2016-04KillmeSarah KmsNo ratings yet

- The Real Ed Lee - The Untold Untold StoryDocument31 pagesThe Real Ed Lee - The Untold Untold Storyauweia1100% (1)

- Itzhak Volansky Trust 2012 Probate (Macdonalds Bookstore Owner)Document46 pagesItzhak Volansky Trust 2012 Probate (Macdonalds Bookstore Owner)auweia1No ratings yet

- 1019market Gomez JudgementDocument3 pages1019market Gomez Judgementauweia1No ratings yet

- Urban Alchemy 2020 990Document28 pagesUrban Alchemy 2020 990auweia1No ratings yet

- DPW Mini-RFP - Urban Alchemy HPFDocument1 pageDPW Mini-RFP - Urban Alchemy HPFauweia1No ratings yet

- TL SOMA Clean Agreement - ExecutedDocument40 pagesTL SOMA Clean Agreement - Executedauweia1No ratings yet

- Piwowar V Safeway - Motion To Compel Plaintiff DepoDocument3 pagesPiwowar V Safeway - Motion To Compel Plaintiff Depoauweia1No ratings yet

- Digiacomo Jr. vs. Tenderloin Housing Clinic February 2020Document31 pagesDigiacomo Jr. vs. Tenderloin Housing Clinic February 2020auweia1No ratings yet

- Leavena Khayat vs. Lee Housekeepper Ud 2007Document11 pagesLeavena Khayat vs. Lee Housekeepper Ud 2007auweia1No ratings yet

- Ivanov V Caritas 51 6th 2020 Stolen PropertyDocument5 pagesIvanov V Caritas 51 6th 2020 Stolen Propertyauweia1No ratings yet

- CHP 2018 990Document45 pagesCHP 2018 990auweia1No ratings yet

- Pitts V CCoSF 2nd Amended Complaint 2019Document19 pagesPitts V CCoSF 2nd Amended Complaint 2019auweia1No ratings yet

- Oakland Community Land Trust - Founding Documents 1999Document75 pagesOakland Community Land Trust - Founding Documents 1999auweia1No ratings yet

- Neslon V San Francisco Department of HomelessDocument36 pagesNeslon V San Francisco Department of Homelessauweia1No ratings yet

- BOS Shelter Amendment14-15Document36 pagesBOS Shelter Amendment14-15auweia1No ratings yet

- Peecher V THCDocument9 pagesPeecher V THCauweia1No ratings yet

- Caritas-Mission Housing V Dotson UD 3048 16th Nuisance 2019Document42 pagesCaritas-Mission Housing V Dotson UD 3048 16th Nuisance 2019auweia1No ratings yet

- Project Homeless Connect 2012 990Document14 pagesProject Homeless Connect 2012 990auweia1No ratings yet

- Caritas V Thomas 175 6th ECS UD NP 2019Document11 pagesCaritas V Thomas 175 6th ECS UD NP 2019auweia1No ratings yet

- Partnership Resources Group Fundraiser Registration 2019Document1 pagePartnership Resources Group Fundraiser Registration 2019auweia1No ratings yet

- "Chapter 9 - Influence Lines For Statically Determinate Structures" in "Structural Analysis" On Manifold @tupressDocument33 pages"Chapter 9 - Influence Lines For Statically Determinate Structures" in "Structural Analysis" On Manifold @tupressrpsirNo ratings yet

- German Din Vde Standards CompressDocument3 pagesGerman Din Vde Standards CompressYurii SlipchenkoNo ratings yet

- Mucosal Adjuvants: Charles O. Elson Mark T. DertzbaughDocument1 pageMucosal Adjuvants: Charles O. Elson Mark T. DertzbaughPortobello CadısıNo ratings yet

- Fujifilm X-E4 SpecificationsDocument5 pagesFujifilm X-E4 SpecificationsNikonRumorsNo ratings yet

- Y10-lab-4-Gas LawDocument10 pagesY10-lab-4-Gas LawEusebio Torres TatayNo ratings yet

- Kitchen Colour Ide1Document6 pagesKitchen Colour Ide1Kartik KatariaNo ratings yet

- Be Project Presentation SuspensionDocument17 pagesBe Project Presentation SuspensionGabrielNo ratings yet

- Revision For The First 1 English 8Document6 pagesRevision For The First 1 English 8hiidaxneee urrrmNo ratings yet

- Alginate Impression MaterialDocument92 pagesAlginate Impression MaterialrusschallengerNo ratings yet

- Disorders of The Endocrine System and Dental ManagementDocument63 pagesDisorders of The Endocrine System and Dental ManagementSanni FatimaNo ratings yet

- CF1900SS-DF Example Spec - Rev1Document1 pageCF1900SS-DF Example Spec - Rev1parsiti unnesNo ratings yet

- TEF5-OFF Frontal Electronic TimerDocument4 pagesTEF5-OFF Frontal Electronic TimerWhendi BmNo ratings yet

- A Bilateral Subdural Hematoma Case Report 2165 7548.1000112 PDFDocument2 pagesA Bilateral Subdural Hematoma Case Report 2165 7548.1000112 PDFPutra GagahNo ratings yet

- 4 TH Sem UG Osmoregulation in Aquatic VertebratesDocument6 pages4 TH Sem UG Osmoregulation in Aquatic VertebratesBasak ShreyaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Science of Guilen Barren SyndromeDocument2 pagesClinical Science of Guilen Barren SyndromemanakimanakuNo ratings yet

- Notes On Peck&Coyle Practical CriticismDocument10 pagesNotes On Peck&Coyle Practical CriticismLily DameNo ratings yet

- 7UM512 CatalogueDocument12 pages7UM512 Cataloguebuianhtuan1980No ratings yet

- TNM Sites May 2023Document24 pagesTNM Sites May 2023Joseph ChikuseNo ratings yet

- Hypochondriasis and Health Anxiety - A Guide For Clinicians (PDFDrive)Document289 pagesHypochondriasis and Health Anxiety - A Guide For Clinicians (PDFDrive)Fernanda SilvaNo ratings yet

- Think Before Buying: ReadingDocument1 pageThink Before Buying: ReadingadrianmaiarotaNo ratings yet

- Morning in Nagrebcan - Manuel E. ArguillaDocument8 pagesMorning in Nagrebcan - Manuel E. ArguillaClara Buenconsejo75% (16)

- Preventive Pump SetDocument67 pagesPreventive Pump Setwtpstp sardNo ratings yet

- 12V-100Ah FTA DatasheetDocument1 page12V-100Ah FTA Datasheetchandrashekar_ganesanNo ratings yet

- Bioclim MaxentDocument9 pagesBioclim MaxentNicolás FrutosNo ratings yet

- Pipe Support Span CalculationDocument14 pagesPipe Support Span Calculationrajeevfa100% (3)

- 4.dole Regulations On Safety Standards in ConstrDocument31 pages4.dole Regulations On Safety Standards in Constrmacky02 sorenatsacNo ratings yet

- Starlift MetricDocument2 pagesStarlift MetricCralesNo ratings yet

- IBH Link UA Manual PDFDocument302 pagesIBH Link UA Manual PDFjavixl1No ratings yet

- 03 Soil Classification Numerical PDFDocument5 pages03 Soil Classification Numerical PDFabishrantNo ratings yet

- Trucks Fin Eu PCDocument117 pagesTrucks Fin Eu PCjeanpienaarNo ratings yet