Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Malabanan vs. Ramento

Uploaded by

clifford tubanaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Malabanan vs. Ramento

Uploaded by

clifford tubanaCopyright:

Available Formats

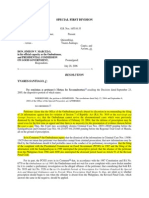

315. MALABANAN VS. RAMENTO [G.R. NO.

62270; 21 MAY 1984]

Facts: Petitioners were officers of the Supreme Student Council of respondent University. They sought

and were granted by the school authorities a permit to hold a meeting from 8:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M, on

August 27, 1982. Pursuant to such permit, along with other students, they held a general assembly at

the Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science basketball court (VMAS), the place indicated in such permit,

not in the basketball court as therein stated but at the second floor lobby. At such gathering they

manifested in vehement and vigorous language their opposition to the proposed merger of the Institute

of Animal Science with the Institute of Agriculture. The same day, they marched toward the Life Science

Building and continued their rally. It was outside the area covered by their permit. Even they rallied

beyond the period allowed. They were asked to explain on the same day why they should not be held

liable for holding an illegal assembly. Then on September 9, 1982, they were informed that they were

under preventive suspension for their failure to explain the holding of an illegal assembly. The validity

thereof was challenged by petitioners both before the Court of First Instance of Rizal against private

respondents and before the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports. Respondent Ramento found

petitioners guilty of the charge of illegal assembly which was characterized by the violation of the permit

granted resulting in the disturbance of classes and oral defamation. The penalty was suspension for one

academic year.

Issue: Whether on the facts as disclosed resulting in the disciplinary action and the penalty imposed,

there was an infringement of the right to peaceable assembly and its cognate right of free speech.

Held: Yes. Student leaders are likely to be assertive and dogmatic. They would be ineffective if during a

rally they speak in the guarded and judicious language of the academe. But with the activity taking place

in the school premises and during the daytime, no clear and present danger of public disorder is

discernible. This is without prejudice to the taking of disciplinary action for conduct, "materially disrupts

classwork or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others."

The rights to peaceable assembly and free speech are guaranteed students of educational institutions.

Necessarily, their exercise to discuss matters affecting their welfare or involving public interest is not to

be subjected to previous restraint or subsequent punishment unless there be a showing of a clear and

present danger to a substantive evil that the state, has a right to present. As a corollary, the utmost

leeway and scope is accorded the content of the placards displayed or utterances made. The peaceable

character of an assembly could be lost, however, by an advocacy of disorder under the name of dissent,

whatever grievances that may be aired being susceptible to correction through the ways of the law. If

the assembly is to be held in school premises, permit must be sought from its school authorities, who

are devoid of the power to deny such request arbitrarily or unreasonably. In granting such permit, there

may be conditions as to the time and place of the assembly to avoid disruption of classes or stoppage of

work of the non-academic personnel. Even if, however, there be violations of its terms, the penalty

incurred should not be disproportionate to the offense.

You might also like

- Malabanan vs. Ramento PDFDocument2 pagesMalabanan vs. Ramento PDFKJPL_1987100% (1)

- JBL Reyes v. Bagatsing DigestDocument1 pageJBL Reyes v. Bagatsing DigestJoshuaLavegaAbrina100% (1)

- Constilaw 2 Digests - Freedom of Speech-Expression-PressDocument35 pagesConstilaw 2 Digests - Freedom of Speech-Expression-PressAlyssa Mae BasalloNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Bayan vs. ErmitaDocument3 pagesCase Digest - Bayan vs. ErmitaMarra Camille Celestial RNNo ratings yet

- Sanidad Vs COMELECDocument2 pagesSanidad Vs COMELECDana Denisse RicaplazaNo ratings yet

- Calleja Vs Executive Secretary DigestDocument15 pagesCalleja Vs Executive Secretary Digestztu32941No ratings yet

- PEOPLE VS TAMPAL CDDocument2 pagesPEOPLE VS TAMPAL CDmark paul cortejosNo ratings yet

- 92 People vs. Alarcon PDFDocument4 pages92 People vs. Alarcon PDFKJPL_1987100% (3)

- PASEI Vs Drilon Liberty of Abode Digest AdvinculaDocument2 pagesPASEI Vs Drilon Liberty of Abode Digest AdvinculaAbby PerezNo ratings yet

- Laud v. People PDFDocument25 pagesLaud v. People PDFHeidiNo ratings yet

- Serafin Vs LindayagDocument1 pageSerafin Vs LindayaggerlynNo ratings yet

- Us V Bustos G.R. No. L-12592 March 8, 1918 Petitioner: THE UNITED STATES Respondent: FELIPE BUSTOS ET AL. DoctrineDocument1 pageUs V Bustos G.R. No. L-12592 March 8, 1918 Petitioner: THE UNITED STATES Respondent: FELIPE BUSTOS ET AL. DoctrineLeslie TanNo ratings yet

- Case 10 - A.C. No 5738 Catu Vs Relossa (Digest) PDFDocument3 pagesCase 10 - A.C. No 5738 Catu Vs Relossa (Digest) PDF莊偉德No ratings yet

- Reyes V Bagatsing 125 SCRA 553Document2 pagesReyes V Bagatsing 125 SCRA 553Adalice MariceNo ratings yet

- Ignacio v. ElaDocument2 pagesIgnacio v. ElaChristopher Anniban SalipioNo ratings yet

- People vs. Judge DonatoDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Judge DonatoDana Denisse RicaplazaNo ratings yet

- Romualdez vs. MarceloDocument10 pagesRomualdez vs. MarceloJolas E. BrutasNo ratings yet

- People v. AlarconDocument1 pagePeople v. AlarconJJ CoolNo ratings yet

- Policarpio Vs Manila TimesDocument1 pagePolicarpio Vs Manila TimesMichelle DecedaNo ratings yet

- Digest Soliven vs. MakasiarDocument1 pageDigest Soliven vs. MakasiarMyra MyraNo ratings yet

- People Vs VallejoDocument18 pagesPeople Vs VallejoJayce MarmetoNo ratings yet

- People V Cayat GR No L-45987 May 5 1939Document5 pagesPeople V Cayat GR No L-45987 May 5 1939kate joan madridNo ratings yet

- Tanada vs. Tuvera Case Digest - 1986Document2 pagesTanada vs. Tuvera Case Digest - 1986claire HipolNo ratings yet

- Baylon VS Judge SisonDocument1 pageBaylon VS Judge SisonSamin Apurillo0% (1)

- Philippine Global Communications Inc v. de VeraDocument1 pagePhilippine Global Communications Inc v. de VeraDwight Anthony YuNo ratings yet

- PBM Employees Association vs. Philippine Blooming MillsDocument2 pagesPBM Employees Association vs. Philippine Blooming MillsDana Denisse RicaplazaNo ratings yet

- Anonymous VDocument5 pagesAnonymous VEnav LucuddaNo ratings yet

- Tatad Vs Sandiganbayan (1988) DigestDocument2 pagesTatad Vs Sandiganbayan (1988) DigestArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Ayer Productions VS CapulongDocument2 pagesAyer Productions VS CapulongAlyssa Mae Ogao-ogaoNo ratings yet

- Calalang Vs WilliamsDocument3 pagesCalalang Vs Williamsmichael jan de celisNo ratings yet

- Burgos, Sr. v. Chief of StaffDocument1 pageBurgos, Sr. v. Chief of StaffDomski Fatima CandolitaNo ratings yet

- MTRCB V ABS CBN Case DigestDocument2 pagesMTRCB V ABS CBN Case DigestJerome C obusanNo ratings yet

- 151639-1948-Philippine Refining Co. Workers Union V.Document6 pages151639-1948-Philippine Refining Co. Workers Union V.Chey DumlaoNo ratings yet

- Facts:: G.R. No. 121234 August 23, 1995Document4 pagesFacts:: G.R. No. 121234 August 23, 1995anna pinedaNo ratings yet

- Corpuz vs. PeopleDocument1 pageCorpuz vs. PeoplePaul Joshua Torda SubaNo ratings yet

- Ichong Vs Hernandez Case DigestDocument4 pagesIchong Vs Hernandez Case DigestJr GoNo ratings yet

- JBL Reyes v. BagatsingDocument2 pagesJBL Reyes v. Bagatsingslumba100% (2)

- Balacuit V CFIDocument2 pagesBalacuit V CFIThea BarteNo ratings yet

- Adiong v. Comelec, 207 SCRA 712 (March 1992)Document11 pagesAdiong v. Comelec, 207 SCRA 712 (March 1992)Lourd CellNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 145184Document10 pagesG.R. No. 145184jiggerNo ratings yet

- Second Division G.R. No. 235652, July 09, 2018 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. XXX AND YYY, Decision Perlas-Bernabe, J.Document6 pagesSecond Division G.R. No. 235652, July 09, 2018 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. XXX AND YYY, Decision Perlas-Bernabe, J.Vanessa GaringoNo ratings yet

- Ramos Vs RadaDocument2 pagesRamos Vs RadaMagr EscaNo ratings yet

- Umil Vs Ramos DigestDocument3 pagesUmil Vs Ramos DigestJo AcadsNo ratings yet

- Philippine Refining Company Worker's Union vs. Philippine Refining Co. (G.R. No. L-1668, March 29, 1948)Document3 pagesPhilippine Refining Company Worker's Union vs. Philippine Refining Co. (G.R. No. L-1668, March 29, 1948)Marienyl Joan Lopez VergaraNo ratings yet

- Alvarez vs. CFI of TayabasDocument1 pageAlvarez vs. CFI of TayabasVince LeidoNo ratings yet

- Zaldivar vs. Sandiganbayan Restrictions On Freedom of ExpressionDocument2 pagesZaldivar vs. Sandiganbayan Restrictions On Freedom of ExpressionRowardNo ratings yet

- United States v. Felipe Bustos Et AlDocument3 pagesUnited States v. Felipe Bustos Et AlSamuel John CahimatNo ratings yet

- Written Assignment 3 - Professional Attire MemorandumDocument3 pagesWritten Assignment 3 - Professional Attire Memorandumapi-330212115No ratings yet

- People Vs FortesDocument1 pagePeople Vs FortesGlenn Robin FedillagaNo ratings yet

- BAYAN Vs ERMITADocument2 pagesBAYAN Vs ERMITACeresjudicataNo ratings yet

- Us Vs BustosDocument2 pagesUs Vs BustosKJPL_1987100% (3)

- Re Letter of Chief Public Atty AcostaDocument2 pagesRe Letter of Chief Public Atty AcostaRaymond Cheng100% (1)

- HIMAGAN Vs PEOPLEDocument1 pageHIMAGAN Vs PEOPLERustom IbanezNo ratings yet

- 01 Ichong v. Hernandez (G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957) PDFDocument2 pages01 Ichong v. Hernandez (G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957) PDFChristine Casidsid67% (3)

- Weems v. US 217 US 349Document2 pagesWeems v. US 217 US 349Jerry CaneNo ratings yet

- GSIS Vs Kapisanan NG Mga ManggagawaDocument5 pagesGSIS Vs Kapisanan NG Mga ManggagawamartinmanlodNo ratings yet

- 14 Carpio Vs GuevaraDocument3 pages14 Carpio Vs GuevaraFaye Jennifer Pascua PerezNo ratings yet

- Malabanan Vs RamentoDocument2 pagesMalabanan Vs RamentoMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Assembly and PetitionDocument5 pagesAssembly and PetitionBananaNo ratings yet

- Consti Digests Sec 4-Sec 12Document26 pagesConsti Digests Sec 4-Sec 12Julius Robert JuicoNo ratings yet

- What Is The Doctrine of Pro ReoDocument4 pagesWhat Is The Doctrine of Pro Reoclifford tubana100% (1)

- Maximo Abano For Respondents. No Appearance For PetitionerDocument5 pagesMaximo Abano For Respondents. No Appearance For Petitionerclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Garcia Vs EnrileDocument2 pagesGarcia Vs Enrileclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Guerzon V Ca FactsDocument9 pagesGuerzon V Ca Factsclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Cert of Non-Forum ShoppingDocument1 pageCert of Non-Forum Shoppingclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Suspensive Vs ResolutoryDocument14 pagesSuspensive Vs Resolutoryclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instrument Lecture NotesDocument2 pagesNegotiable Instrument Lecture Notesclifford tubana100% (1)

- Ricardo Vs Gen. Renato de VillaDocument1 pageRicardo Vs Gen. Renato de Villaclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Amarga Vs AbbasDocument2 pagesAmarga Vs Abbasclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- 159 People Vs Ang Chun KitDocument1 page159 People Vs Ang Chun Kitclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Gutierez Vs DBMDocument1 pageGutierez Vs DBMclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Reflective Essay: My Experience Creating An EportfolioDocument3 pagesReflective Essay: My Experience Creating An EportfolioAnghel BrizNo ratings yet

- Five Conversations FrameworkDocument4 pagesFive Conversations FrameworkscorpionrockNo ratings yet

- Opening Remarks For OrientationDocument2 pagesOpening Remarks For OrientationBucoy David83% (6)

- Check List - Product Realisation ProcessDocument4 pagesCheck List - Product Realisation ProcessDisha ShahNo ratings yet

- Company Vinamilk PESTLE AnalyzeDocument2 pagesCompany Vinamilk PESTLE AnalyzeHiền ThảoNo ratings yet

- How To Fight Presidents by Daniel O'Brien - ExcerptDocument8 pagesHow To Fight Presidents by Daniel O'Brien - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group100% (1)

- Third Conditional WorksheetDocument4 pagesThird Conditional WorksheetGeorgiana GrigoreNo ratings yet

- Do You Know How To Apply For ADocument7 pagesDo You Know How To Apply For ATrisaNo ratings yet

- Aalto Et Al Eds - International Studies, Interdisciplinary ApproachesDocument293 pagesAalto Et Al Eds - International Studies, Interdisciplinary ApproachesSteffan Wyn-JonesNo ratings yet

- Page 73 ActivityDocument2 pagesPage 73 ActivityGodisGood AlltheTimeNo ratings yet

- Pecs BookDocument2 pagesPecs BookDinaliza UtamiNo ratings yet

- Fatal Charades Roman Executions Staged AsDocument33 pagesFatal Charades Roman Executions Staged AsMatheus Scremin MagagninNo ratings yet

- OWWAFUNCTIONSDocument4 pagesOWWAFUNCTIONSDuay Guadalupe VillaestivaNo ratings yet

- Physics Stage 6 Syllabus 2017Document68 pagesPhysics Stage 6 Syllabus 2017Rakin RahmanNo ratings yet

- SHS Contextualized Research in Daily Life 2 CGDocument6 pagesSHS Contextualized Research in Daily Life 2 CGGerald Jem Bernandino100% (2)

- RESUME Moleta Gian Joseph F.Document3 pagesRESUME Moleta Gian Joseph F.Gian Joseph MoletaNo ratings yet

- Azu Etd 13902 Sip1 MDocument301 pagesAzu Etd 13902 Sip1 Mlamaga98No ratings yet

- Music: Quarter 1 - Module 1: TitleDocument41 pagesMusic: Quarter 1 - Module 1: TitleAthena JozaNo ratings yet

- GMAT Critical Reasoning PracticeDocument13 pagesGMAT Critical Reasoning PracticeJananee KumaresanNo ratings yet

- Use Case DiagramsDocument8 pagesUse Case DiagramsUmmu AhmedNo ratings yet

- Zambia Revenue AuthorityDocument17 pagesZambia Revenue AuthoritycholaNo ratings yet

- WRITING SUMMER 2021 - Pie Chart & Table - CT2.21Document13 pagesWRITING SUMMER 2021 - Pie Chart & Table - CT2.21farm 3 chi diNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Cyber SecurityDocument17 pagesChapter 4 - Cyber SecurityAnurag Parate100% (1)

- IRR of RA NO. 9167 Film Devt Council of The PhilippinesDocument12 pagesIRR of RA NO. 9167 Film Devt Council of The Philippinesquickmelt03No ratings yet

- Causes To Translation ErrorsDocument16 pagesCauses To Translation Errorsbom2007No ratings yet

- Details About TOK - CAS Visit To ShantipurDocument2 pagesDetails About TOK - CAS Visit To ShantipurINDRANI GOSWAMINo ratings yet

- Elsevier Journal FinderDocument4 pagesElsevier Journal FinderLuminita PopaNo ratings yet

- TP Project Report FinalDocument32 pagesTP Project Report FinalalvanNo ratings yet

- Tourism IndustryDocument22 pagesTourism IndustryKrishNo ratings yet

- MGM102 Test 1 SA 2016Document2 pagesMGM102 Test 1 SA 2016Amy WangNo ratings yet