Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Regional Plan Association Coastal Adaptation Report (2017)

Uploaded by

RiverheadLOCALOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Regional Plan Association Coastal Adaptation Report (2017)

Uploaded by

RiverheadLOCALCopyright:

Available Formats

Coastal Adaptation

A Framework for Governance and Funding

to Address Climate Change

A Report of The Fourth Regional Plan

October 2017

Acknowledgments

This report highlights key recommendations from RPA’s Fourth Regional Plan for the

New York-New Jersey-Connecticut metropolitan area. The full plan will be released in November 2017.

The Fourth Regional Plan has been made possible by

Major support from And additional support from

Rohit Aggarwala New Jersey Institute of

The Ford Foundation Peter Bienstock Technology

The JPB Foundation Brooklyn Greenway Initiative New York State Energy Research

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Doris Duke Charitable and Development Authority

Foundation (NYSERDA)

The Rockefeller Foundation Emigrant Bank Open Space Institute

Friends of Hudson River Park PlaceWorks

Grants and donations from Fund for New Jersey Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Albert W. & Katharine E. Merck Charitable Fund Garfield Foundation Robert Sterling Clark Foundation

Anonymous Greater Jamaica Development Rutgers University

Fairfield County Community Foundation Corporation Shawangunk Valley Conservancy

Fund for the Environment and Urban Life/Oram Town of Hackettstown Stavros Niarchos Foundation

Laurance S. Rockefeller Fund Suffolk County

Foundation Leen Foundation Two Trees Foundation

JM Kaplan Fund Lily Auchincloss Foundation Upper Manhattan Empowerment

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy National Park Service Zone

New York Community Trust New Jersey Board of Public Volvo Research and Education

Rauch Foundation Utilities Foundations

New Jersey Highlands Council World Bank

Siemens

We thank all our donors for their generous support for our work.

This report was produced by RPA wishes to especially thank the following for their

advice and contributions to the report:

Lucrecia Montemayor, Deputy Director, Steve Adams, Institute for Sustainable Staff at the following departments

Energy & Environment, RPA Communities and commissions:

Emily Korman, Research Analyst, Bennett Brooks, Consensus Building Bay Area Regional Collaborative

Energy & Environment, RPA Institute California Coastal Commission

Robert Freudenberg, Vice President, Joyce Coffee, President, Climate Chesapeake Bay Program

Energy & Environment, RPA Resilience Department of Energy & Environmental

Ellis Calvin, Senior Planner, Energy & Amy Cotter, Lincoln Institute for Land Protection

Environment, RPA Policy Louisiana Coastal Protection and

Sarabrent McCoy, Research Analyst, Carri Hulet, Consensus Building Institute Restoration Authority

Energy and Environment, RPA Dina Long, Mayor, Sea Bright, New Jersey New York Department of State

Chris Jones, Senior Vice President & Marvin Markus, Goldman Sachs New Jersey Department of

Chief Planner, RPA Nick Shufro, FEMA Environmental Protection

Dani Simons, Vice President for Maura Spery, Former Mayor, Mastic Puget Sound Regional Council on Climate

Strategic Communications, RPA Beach, NY Resiliency

Emily Thenhaus, Strategic Interstate Environmental Commission

Communications Associate, RPA San Francisco Bay Conservation and

Jesse Keenan, Harvard University, Development Commission

Graduate School of Design San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority

Ben Oldenburg, Senior Graphic Southeast Florida Regional Climate

Designer, RPA Compact

Cover Image: Roman Babakin

Contents

Executive Summary / 2

A Growing Crisis / 4

Who Governs Our Coastline Today? / 8

A Vision for Regional Governance and

Dedicated Adaptation Funding / 14

Adaptation Trust Funds / 17

Implementing a Regional Coastal Commission:

Best Practices from Around the Country / 20

Next Steps / 25

Appendix: Models Around the Country / 26

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 1

Executive Summary

Over the next 30 years, the number of people living in ⊲⊲ Coastal flooding is a regional problem, but most plan-

places at risk of flooding from an extreme storm in the New ning happens locally. Each state and municipality has

York-New Jersey-Connecticut region is likely to double different rules, policies and guidelines, and limited

from 1 million to 2 million. Sea levels are projected to rise incentives to collaborate. Coastlines and infrastructure

by two feet, putting 10,000 homes permanently under transverse government boundaries, and since water is

water and greatly expanding the coastal floodplain. With fluid, management practices in one state or municipal-

over 3,700 miles of tidal coastline, much of it densely popu- ity can have an inadvertent impact on others.

lated with old and decaying infrastructure, the region’s

states and local communities face the daunting challenge ⊲⊲ State coastal management programs leave several

of making the physical and regulatory changes necessary problems unaddressed. The coastal management pro-

to adapt to this new coastline. Restoring wetlands, building grams of the three states vary widely in approach, and

sea walls, raising buildings, retrofitting infrastructure and inconsistent policies can prevent important adaptation

buying out vulnerable homeowners are among the actions strategies from being implemented across state lines. At

that 167 coastal cities, towns, villages and counties will the same time, adaptation is not a singular focus of any

need to consider and find the resources to implement. program, nor are issues of regional significance, such as

infrastructure.

While there has been substantial progress in planning for

climate change, adaptation is slow, sporadic, underfunded

and uncoordinated. Attention and resources rise in the

wake of storms like Superstorm Sandy, but soon dissipate A Coastal Commission

when the immediate crisis has passed. In many ways, the

needs are so great and the timeframes for implementation for the Tri-State Region

are so long that it is easier to focus on more immediate

needs. While Superstorm Sandy provided an infusion of To give climate adaptation the priority it needs and to be

funding for recovery and adaptation, there remains $28 able to implement solutions at different geographic scales,

billion worth of identified needs that has not been funded.1 New York, New Jersey and Connecticut should create a

To get ahead of the growing crisis, the region will need to Regional Coastal Commission (RCC). The commission

overcome several impediments: would be empowered to maintain a dedicated focus on

the region’s climate adaptation needs, help mobilize the

⊲⊲ Planning and investments are reactive rather than proac- region’s resources to address them, coordinate strategies

tive. There is neither a plan nor a budget for adaptation and develop common standards. It would also prioritize

projects that can prioritize investments and prepare for funding that can be used for region-wide resilience proj-

future contingencies. Instead, current funding sources ects. Based on successes and lessons learned from other

and policies depend on unreliable federal funding that coastal commissions, the RCC would have the following

promotes short-term recovery over long-term invest- responsibilities:

ments.

⊲⊲ Produce and update a regional coastal adaptation plan

⊲⊲ Most of the region’s smaller cities, towns and villages that aligns policies across municipal and state boundar-

have limited capacity. The vast majority of the region’s ies and sets a vision for short-term resilience and long-

municipalities are governed by part-time or volunteer term adaptation.

mayors and councils, and even the larger municipalities

lack the staff capacity and resources to address and plan ⊲⊲ Develop and manage science-informed standards to

for long-term climate changes. guide and prioritize adaptation projects and develop-

1 Keenan, J.M. (2017). Regional Resilience Trust Funds: An Exploratory ment in the region’s at-risk geographies.

Analysis for the New York Metropolitan Region. New York, NY.: Regional Plan

Association. http://library.rpa.org/pdf/Keenan-Regional-Resilience-Trust-

Funds-2017.pdf

2 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

Over the next 30 years, 59% of the region’s

energy capacity will be in areas prone to

flooding, as will all of our shipping ports,

four of our major airports, 21% of our public

housing units and 12% of our hospital beds.

⊲⊲ Coordinate and encourage collaborative adaptation sources. Through the utilization of bond leverage, the funds

projects across municipal and state boundaries. could operate independently and without subsidy from the

insurance surcharges within a 10 year sunset period.

⊲⊲ Evaluate and award funding from new adaptation trust

funds that align with standards established by the com-

mission.

Coastal Commission

Governance

State Adaptation

Membership and governance of the Regional Coastal

Trust Funds Commission could take a number of forms, but should be

guided by the best practices of other coastal commissions

The Regional Coastal Commission needs funding to and regional collaboratives. Members should be designated

fulfill its mission. We propose establishing new dedicated across jurisdictions (state, county and local) and should be

resources from adaptation trust funds to be established in representative of different coast types (urban, suburban

each state. 2 The trust funds would be organized as public and more natural conditions). Elected officials could have a

benefit corporations and would be initially capitalized role on the commission to give it legitimacy and visibility,

from surcharges on property and casualty premiums. The but the governance structure must remain independent

funds would be managed by each state, but oversight and from political cycles and direct political interference. Both

authority to underwrite and allocate the funds as grants members and staff should include a variety of disciplines

and loans would rest with the commission. Each state trust to embed all aspects of resilience planning into decisions.

fund would finance a minimum amount of in-state proj- The commission’s work should be informed by the latest

ects, while residual allocations would be prioritized for science and flexible enough to shift as conditions along the

those projects and programs whose benefits would extend dynamic coast change over time. Funding allocations and

beyond jurisdictional boundaries. The grants and loans project selection should be guided by a clear set of stan-

could support a range of projects, from short-term commu- dards and evaluation metrics.

nity resilience planning to long-term infrastructure finance

and could be used to leverage or match other funding

2 Keenan, J.M. (2017). Regional Resilience Trust Funds: An Exploratory Anal-

ysis for Leveraging Insurance Surcharges. Environment Systems and Decisions.

doi: 10.1007/s10669-017-9656-3

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 3

A Growing Crisis

Across the globe, communities are beginning to grapple

with the reality that they will need to adapt to the changing A Changing Coastline is

climate around them. Even if the goals of the Paris Climate

Accord are reached, the climate has already — and will

Dramatically Increasing Risks

continue — to change in ways that make adaptation neces-

sary. Coastal communities will flood more frequently, some Nowhere is this crisis more acute than along our dynamic

permanently. More intense rainfalls will overwhelm the coastline. The New York-New Jersey-Connecticut metro-

infrastructure of the built environment. Hotter days will politan region, with over 3,700 miles of tidal coastline and

threaten the public health of the most vulnerable popula- 23 million residents settled into highly urbanized places

tions and test the integrity of our infrastructure, creating with old and decaying infrastructure, faces an impend-

higher demand for energy and burning more of the fuels ing crisis. Today, just over one million regional residents

that have caused this problem in the first place. live in places at risk of flooding from an extreme storm. By

2050 — with approximately 2 feet of sea level rise — that

number will nearly double to around 2 million. Similarly,

the risk of permanent flooding from sea level rise inunda-

tion is also significant. As detailed in RPA’s report Under

Water (2016), one foot of sea level rise (possible as soon as

the 2030’s) could inundate nearly 60 square miles where

more than 19,000 residents in 10,000 homes live today, and

where approximately 10,000 people work. Three feet of sea

level rise (possible by 2080) could inundate over 130 square

miles where nearly 114,000 residents in 68,000 homes live

today, and where some 62,000 jobs are currently located.

Six feet of sea level rise (possible by 2100) could inundate

280 square miles where 619,000 residents in 308,000

homes live today, and where more than 362,000 of today’s

jobs are located.

At the same time vital pieces of infrastructure that keep

our region connected and thriving are located in these

same floodplains. Today, 28% of our energy-generating

capacity is located in areas that have a 1% chance of flood-

ing in any given year. By 2050, 59% of our energy capacity

will be in areas prone to flooding, as will all of the region’s

shipping ports, four of our major airports, 21% of our public

housing units and 12% of our hospital beds.

Road flooded during high

tide in Mastic Beach, NY

4 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

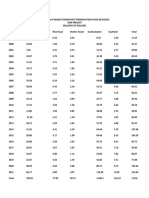

Vulnerable infrastructure

In region In current flood plain In 2050 flood plain

2015 population 22,850,769 1,106,438 5% 1,941,959 8%

Public housing units 228,317 19,868 9% 47,382 21%

Hospital beds 80,426 5,112 7% 9,214 12%

Nursing home beds 140,862 6,750 5% 11,145 8%

Electric generation capacity (MWh) 32,636 9,127 28% 19,181 59%

Train stations 905 62 7% 115 13%

Train tunnels 12 12 100% 12 100%

Subway yards 21 4 4% 7 33%

Major airports 6 4 67% 4 67%

Shipping ports 6 6 100% 6 100%

Sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; American Hospital Directory; NJ HSIP Health Facilities; American Hospital Directory; U.S. Department of

Housing and Urban Development; Energy Information Administration; Metropolitan Transportation Authority; New Jersey Transit; Port Authority of New York and

New Jersey; ESRI; U.S. census; FEMA; The Nature Conservancy

There is Neither a Plan Nor a Budget

In the past twenty years,

for Adaptation in the Region

Addressing this crisis will require broad and significant

638 damaging

investment to improve protection for many communities,

buy-out those most at-risk in lower density neighborhoods,

flooding events*

upgrade energy, wastewater and transportation infrastruc-

ture, secure contaminated sites and restore and make room

in our coastal

for the benefits of nature. Investments in adaptation are

likely to be amongst the largest expenditures we make as a

counties have

region over the next generation, but we have neither a plan

nor a budget for them. Instead, we are largely stuck in a

accounted for:

vicious and perverse cycle of needing catastrophic storms

— and the recovery dollars they bring — to pay for adapta-

tion projects. Most recent recovery and adaptation funding

73 direct fatalities

has come from the federal government. But due to shifts in

politics and policy, it is very likely that future disasters will

come with the requirement that states pay a greater share

112 direct injuries

for recovery. 3 What’s more, current funding sources and

recovery policies continue to incentivize risky development

and promote short-term recovery over long-term adapta-

12 indirect fatalities

tion.

14 indirect injuries

The Region’s Municipalities *Days on which a flooding event occurred, as tracked and

reported by NOAA National Centers for Environmental In-

formation’s Storm Events Database. Only those events which

Have Limited Capacity to caused or threatened acute damage were included by NOAA

in the database.

Address Coastal Flooding

As the effects of climate change, like flooding, become more

severe, more municipalities will have to respond more fre-

quently, issuing warnings ahead of events, providing emer-

gency services during and after, communicating with risk

management agencies, assessing damage, managing the

3 A proposed federal rule known as the Public Assistance Deductible would

require states to cover a fix dollar amount for any given federal disaster prior to

FEMA’s provision of public assistance for the repair and replacement of public

infrastructure damaged by a disaster event. At the time of publication, this rule

was still being evaluated. See FEMA Docket ID FEMA-2016-003.

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 5

Oakwood Beach, Staten Island

Due to damage from Hurricane Sandy in 2012, properties in some

high-risk areas were acquired with buy-out programs to be used as

buffers against future flooding.

recovery process, and finally helping to invest in and man- tion and stormwater management challenging to address.

age repairs and other recovery and adaptation measures. This fragmented governance makes it nearly impossible to

And they will need to do all of this with limited capacity address the effects of climate change in a comprehensive

and tight budgets. Many of the region’s municipalities are and effective way. As flooding affects more of the region’s

governed by part-time or volunteer mayors and local coun- infrastructure, regional decisionmaking will become

cils. Thus, the effects of climate change, such as frequent even more important to ensure quality of life in individual

or extreme flooding, represent a significant and additional municipalities.

obligation that all too many towns are not equipped to

manage. Absent regional collaboration and stable funding, dis-

jointed approaches across misaligned timelines will be the

norm, with each community or agency competing for the

Coastal Flooding Is a Regional Risk same limited pots of funding. Perhaps no place illustrates

the problem more than the New Jersey Meadowlands, a

that Is Largely Managed Locally patchwork of road, rail, wastewater and energy infrastruc-

ture, interwoven with businesses, communities and natural

While flooding knows no municipal boundary, our region’s systems, all at significant risk of flooding from sea level rise

edge is governed by multiple stakeholders with differ- and storms. As conditions worsen, a comprehensive adapta-

ent rules, policies, and guidelines, with few incentives to tion plan for all of these entities, carried out with clear

collaborate or coordinate with one another. The lack of timelines and adequate funding, will be essential to ensure

guidance in terms of standards, unified science and data that this critical confluence of infrastructure remains a key

across agencies and states makes it difficult to consolidate part of the region’s economy or ecosystem.

or share information across jurisdictions or advocate for a

unified long-term vision. The result is poor inter- and intra-

governmental coordination and conflicting interests, and

communities taking actions to protect themselves that can

have adverse impacts on surrounding communities. Design

teams that participated in the 2014 Rebuild by Design com-

petition found that lack of regional coordination between

municipalities can make issues like ecological restora-

6 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

The seriousness of the region’s exposure to flood

risk is underscored not just by its geographic extent,

which crosses all political boundaries, but also by

the density of people and infrastructure at risk.

Density of People and Infrastructure Exposed to the Projected 2050 Floodplain

Source: Regional Plan Association

Low High

Ulster Population and

Dutchess Litchfield

Sullivan infrastructure density

New Haven

Putnam

Orange

NY

NJ Fairfield

Westchester

NY

Sussex Rockland CT

Passaic

Bergen

Warren Morris Suffolk

Bronx

New

Essex York Nassau

Queens

Hudson

Union

Kings

Hunterdon

Richmond

Somerset

Bergen

Middlesex

Passaic

Bronx

Mercer

Monmouth

Essex New

York

Ocean Queens Nassau

Hudson

Union

Richmond

Middlesex

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 7

Who Governs Our Coastline Today?

Whether at the federal, state or local level of government, management of the nation’s coastal resources across state

managing the process of climate change adaptation is lines. Under the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA),

complicated and shared across multiple divisions. Issues eligible states can create their own individual CMPs so they

around water, air and habitat quality are managed by envi- can best address local challenges, working within state and

ronmental agencies. Maintaining and upgrading highways local laws and regulations. At the same time, participating

and rail lines are managed by transit and transportation states must abide by the basic federal requirements stipu-

agencies and local authorities. Land use and building deci- lated in the CZMA.

sions are made by planning, zoning, housing and develop-

ment agencies. A host of other decisions, from adaptation Once a state’s CMP is federally recognized, it can receive

in parks to coastal engineering are made within and across administrative and grant funding from NOAA to enhance

relevant agencies. All require input, decision-making and their programs. To incentivize cooperation with the

action from local governments. More than 20% of the National Program, the Federal Consistency Provision (16

region’s municipalities (167) face a future of coastal flood- U.S.C. § 1456. Coordination and cooperation (Section 307),

ing (either intermittent from storms or permanent from sea (c)), ensures that federal actions with reasonably foresee-

level rise). Adapting these communities and the infrastruc- able effects on coastal uses and resources are consistent

ture that serves them will require increased collaboration with the enforceable policies of a state’s approved CMP.

and smoother processes, particularly as capacity at the This provision gives participating states a stronger voice in

local level is limited in many municipalities. federal agency decision making than they would not have

otherwise for activities that may affect their coastline.

In addition to the National Coastal Management Program,

Coastal Management the federal government also helps to manage and regu-

late coastal development in at-risk areas with flood stan-

Programs dards for federally-funded projects as well as by requiring

residents in flood zones to participate in FEMA’s National

With a few exceptions at the municipal level, coastal Flood Insurance Program, which is federally subsidized

adaptation today is largely managed by coastal manage- insurance for homes in FEMA-designated floodplains.

ment programs, federally authorized programs that are Premiums for insurance are reduced for those homes with

managed differently in each state. The following describes more resilient features, though the program does not dis-

the national program and summarizes the ways in which courage residents from being in the flood zone.

each program is carried out in New York, New Jersey and

Connecticut. Coastal Management Programs in the Region

Today, thirty-four of the U.S.’s thirty-five coastal states

The National Coastal Zone Management Program have federally recognized Coastal Management Programs,

Authorized by the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, including New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. There

the National Coastal Zone Management Program is a is minimal interstate coordination between these three

voluntary partnership between the federal government and programs, despite their shared coastlines.

coastal and Great Lakes states and territories focused on

protecting, restoring and responsibly developing coastal New York’s CMP, the second most robust program after

communities and resources.4 Administered by the National California’s, is embedded into the state’s governmental

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the structure, which allows regulators to set the tone for rules

program aims to address pressing coastal issues such as and regulations relating to the coast and coastal develop-

climate change, ocean planning, and planning for energy ment. In contrast, the New Jersey CMP is seen as a federal

facilities and development and encourage smart, consistent program within the state, with most of its funding from

4 NOAA Office for Coastal Management website, accessed October 2017.

federal sources, while Connecticut uses its CMP mostly as

https://coast.noaa.gov/czm/ a regulatory agency, issuing and approving permits.

8 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

The underlying foundation of our region’s three active in and out of the coastal management zone and will require

Coastal Management Programs (CMPs) is the same — all continued adaptation, is not the specific charge of coastal

three states have limited regulatory power over land use management programs. Issues such as these pose a signifi-

planning in individual communities, and consequently cant challenge for creating a comprehensive, consistent

work to guide their communities towards certain practices. long-term adaptation strategy across the region’s coast.

However, the varying ways in which each entity views and

values its natural resources makes the structure, policies, Climate Change and the State Coastal

interpretation, and implementation of the three programs Management Programs

vastly different. New York State and Connecticut both have specific leg-

islative mandates to consider different aspects of climate

The New York State Department of State (DOS) views itself change in their Coastal Management Programs. New

as the administrator to one of the largest and most impor- York York State’s Community Risk and Resiliency Act

tant CMPs in the United States, second only to California’s (CRRA) — being implemented largely by the Department

program. As the State’s chief planning and development of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and the Depart-

agency, DOS makes a conscious effort to both influence ment of State (DOS) — addresses climate change and sea

policy set by its municipalities and learn from how com- level rise and enables collaboration between individual

munities shape policies to reflect their unique priorities. It municipalities and other state agencies to identify and plan

does this largely through its Local Waterfront Revitaliza- for their coastal vulnerabilities.5 The law ensures that dif-

tion Program, which offers local governments the oppor- ferent aspects of climate change are accounted for in their

tunity to voluntarily demonstrate consistency with the activities and programs. Under CRRA, NYS DOS and DEC

Coastal Management Program by preparing and adopting a develop model local laws that consider risk from sea level

local waterfront revitalization program. For example, New rise, storm surge, and flooding; and DEC and DOS develop

York City’s Waterfront Revitalization Program establishes guidance for how to use natural resources and processes to

the City’s policies for waterfront planning, preservation enhance resilience. Meanwhile, Connecticut’s 2012 Public

and development projects, carried out by its planning Act 12-101 incorporated sea level rise into the Connecti-

department. cut CMP by requiring planners and developers consider

the potential impact of sea level rise, coastal flooding, and

In contrast with its northern neighbor, New Jersey’s pro- erosion patterns on coastal development.6 For New Jer-

gram seeks to provide municipalities with the information, sey, there is no specific regulation within the State’s CMP

tools and technical assistance to make informed decisions. that requires municipalities account for various aspects

Connecticut, on the other hand, views its program as of climate change. However, NJDEP’s Office of Coastal

largely a regulatory agency, that enforces its policy direc- and Land Use Planning has created tools to help coastal

tion through permitting, but with an important secondary municipalities account for climate change in various plan-

planning role. From its initial creation, New York’s program ning activities.7 Furthermore, the State uses its regulatory

was organized to be an inter-agency, publically-vetted, permitting authority to set strict standards for development

consistent process, with an iterative structure and active in the coastal zone.

feedbacks between different levels of government. This

structure seems to create more consistent, effective coastal Following catastrophic storms, including Superstorm

management policies than its neighboring states. Sandy, New York in 2013 established the Governor’s Office

of Storm Recovery in order to centralize recovery and

Regardless, currently each state’s program acts indepen- rebuilding efforts in the state. Today, the office continues

dently from its neighbors, coordinating efforts on an ad hoc to oversee programs related to housing, small business,

basis when a project or a specific issue requires it. Incon- community and infrastructure improvements, including

sistent policies can prevent important adaptation strategies buyouts for willing municipalities. The agency is sched-

from continuing across state lines, creating piecemeal strat- uled to sunset in 2022, when funds are fully dispersed and

egies which can leave vulnerable gaps or hinder the effec- recovery work completed.

tiveness and impact of any one project. For example, New

York City’s Billion Oyster Project, an ecosystem restoration New Jersey’s Blue Acres program is a state buyout program

initiative that is harvesting one billion live oysters in the established to purchase floodprone properties from willing

New York Harbor to restore reefs and increase protective sellers. Originally funded through bonding, the program

habitat, cannot be implemented across the entire Harbor received an additional boost of funding from Superstorm

because the practice is illegal in New Jersey. 5 “Community Risk and Resiliency Act (CRRA)”. New York State Department

of Environmental Conservation website. Accessed October 2017. http://www.

dec.ny.gov/energy/102559.html

At the same time, adaptation is just one of multiple charges 6 “Guidance on P.A. 12-101, An Act Concerning the Coastal Management Act

and Shoreline Flood and Erosion Control Structures.” State of Connecticut De-

that coastal management programs have in each state, partment of Energy and Environmental Protection. November 10, 2016. http://

meaning there are multiple — and sometimes conflicting www.ct.gov/deep/cwp/view.asp?a=2705&pm=1&Q=512226&depNAV_GID=1622

7 “Coastal Hazards of New Jersey: Now and with a Changing Climate.” New

— issues to manage around coastal land and water uses. Jersey Department of Environmental Protection website. Accessed October

Coastal infrastructure that spans state boundaries, weaves 2017. http://www.state.nj.us/dep/cmp/czm_hazards.html

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 9

Sandy federal recovery dollars and has since received addi- Long Island South Shore Estuary Reserve

tional funding through the state’s Corporate Business Tax. Administered by New York State Department of State, the

To date, buyouts have occurred primarily along riverine South Shore Estuary Reserve extends from the Nassau/

floodplains. In Connecticut, a limited number of buyouts Queens line to the Village of Southampton, from the bar-

have taken place through the USDA Watershed Protection rier islands’ mean high tide line to the inland limits of the

and Flood Prevention Program. drainage area. The Reserve is charged with preparing and

advising implementation of a comprehensive management

plan aimed at improving and maintaining water quality;

supporting living resources; expanding public use; sustain-

Regional Estuary & Estuarine ing the estuary economy; and supplementing stewardship

and outreach11 .

Reserve Programs

New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program

In addition to coastal management programs, which focus With a geographic footprint including the Hudson River

largely on the built environment in coastal areas, there are watershed and the watersheds of the Raritan, Passaic, and

a number of estuary and estuarine reserve programs in our Hackensack Rivers, but a core area focus on the Hudson-

region that focus on the quality and protection of estuar- Raritan Estuary, the Program works to restore and protect

ies of significant importance. These programs also serve a healthy waterways, manage sediments, encourage commu-

critical role educating the general public about the impor- nity stewardship, and improve access12 .

tance of estuaries, particularly as climate change alters our

coastline and threatens our communities. Just as our com- Barnegat Bay Partnership

munities will need to adapt, so will our natural systems. At A partnership of federal, state, municipal, academic, busi-

the same time, protecting and restoring natural systems ness, and private organizations, the Barnegat Bay oversees

will help to shield the built environment from flooding and comprehensive planning for the estuary and watershed

storm damage. These programs will be important partners that cover most of Ocean County and some of Monmouth

in advancing adaptation, and include: County, NJ. The role of the Partnership is to support

consensus building and problem solving between agen-

Hudson River Estuary Program cies charged with restoring, protecting, and enhancing the

Working within the tidal Hudson and adjacent watershed, natural resources of the namesake ecosystem13 .

from New York City up to Troy, the Hudson River Estuary

Program oversees restoration projects, protects land, facili-

tates educational opportunities, and monitors and maps

river conditions 8 . Municipal Coastal

Long Island Sound Study Governance

Formed by EPA, New York, and Connecticut, the Long

Island Sound Study is a partnership between agencies, The role of a municipality in governing in the coastal zone

user groups, and other organizations. Since 1994, they have differs slightly, depending on which state it is located

made strides restoring habitats, monitoring water quality, within. In general, our region abides by “home rule,”

educating the public, and reducing nutrient loads in the meaning all municipalities are free to pass their own laws

1,300 square-mile Sound over which they preside9. and ordinances, provided they comply with federal, state

or regional authority laws and regulations. This applies

Peconic Estuary Program to local land use decisions, including how municipalities

With a study area extending from the headwaters of the choose to develop coastal land. Still, given decades of

Peconic River to Block Island Sound, the Peconic Estu- increased environmental and other regulations along the

ary Program is charged with creating and implementing fragile coast, many municipalities must navigate a tangled

a comprehensive management plan to protect the estuary, network of agencies and regulations when making land

support habitat, educate the public, and improve water use decisions. Following a disaster, the federal funds that

quality10. largely pay for recovery often have stricter limitations (e.g.

rebuild heights) that local municipalities must comply with

as a condition of accepting public funds.FEMA’s National

Flood Insurance Program also offers a voluntary incentive

8 “Hudson River Estuary Program.” New York State Department of Envi- 11 “South Shore Estuary Reserve Home.” New York State Department of State

ronmental Conservation. Accessed October 2017. http://www.dec.ny.gov/ Office of Planning & Development. Accessed October 2017. https://www.dos.

lands/4920.html ny.gov/opd/sser/index.html

9 “About the Long Island Sound Study.” Long Island Sound Study. Accessed 12 “About the Program.” New York/New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program.

October 2017. http://longislandsoundstudy.net/about/about-the-study Accessed October 2017. http://www.harborestuary.org/about.htm

10 “The Peconic Estuary Story.” Peconic Estuary Program. Accessed October 13 “Barnegat Bay Partnership Mission.” Barnegat Bay Partnership. Accessed

2017. https://www.peconicestuary.org/discover-the-peconic/the-peconic- October 2017. https://www.barnegatbaypartnership.org/about-us/bbp-mis-

estuary-story/ sion/

10 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

Protecting just

Our coastal areas involve a complex layer of governmental

jurisdictions. Take, for example, this parcel of land in the

one parcel of land in

borough of Sea Bright, New Jersey. Just this one strip of

land is subject to the management and oversight of a multi-

Sea Bright, New Jersey

tude of local, state and federal entities. Following a disas-

ter, the amount of coordination required between

them for recovery and adapta-

tion can test the limits of a Sandy Hook Bay

municipality’s capacity.

US EPA

Requires regular monitoring of water impairment. NY

NJ

NY

Administers the National Estuary Program, of CT

which the New York - New Jersey Estuary Pro-

NJ Division of Fish and Wildlife’s gram is a part. Regulates point sources that dis- Atlantic Ocean

Bureau of Land Management charge pollutants into waterways.

Preserved as a Wildlife Management Area, MONMOUTH

regulates recreational use New York–New Jersey COUNTY Sea Bright

Harbor Estuary Program

FEMA Develops and manages a Comprehensive Conser-

Deemed ineligible (Coastal Barrier Re-

vation and Management Plan for the New York - Shrewsbury

sources Act, 1982) for most federal finan-

New Jersey Harbor Estuary. Management Confer- River

cial assistance and development incen-

ence provides open forum for discussion, plan-

tives, including federal flood insurance.

ning, and action on issues facing the Estuary.

Promoted conservation.

NJDEP

NJ DEP Division of Require, define, and authorize specific stream NJ DEP Division of

Land Use Regulation cleaning practices. Promotes projects which pre- Coastal Engineering

Regulates activities (dredging, filling, re- Serves as administrator of repair, gap US EPA

serve habitat, limit work adjacent to the channel. Sets water quality standards, au-

moving, or otherwise altering or pollut- Determines compliance with the Flood Hazard bridging efforts. Funded restoration in

ing) within coastal wetlands, inventories part. thorizes grants to state to moni-

Area Control Act rules. tor beaches. Monitors and assists

boundaries.

Water (Inland) USACE with Clean Water Act compliance.

USFWS Collaborated with Borough and DEP on

Is involved in permit review programs seawall design and funding. NOAA

for regulated activities in wetland Sets and monitors tide stations,

FEMA provides data for the defining the

High/Low Marsh Funded majority of repair and gap clo- shoreline and its tidal datum vari-

sure of seawall. Obligated the project ations - and the jurisdictional

Wetlands in November 2015. boundaries defined by these vari-

ations.

Municipality

Orchestrated collaboration between NJ US FWS

DEP and USACE on seawall repair Conducts environmental contam-

design and funding. inant studies, Natural Resource

Damage Assessments

Sea Wall

NJ DEP Department of Land

Use Management

Plan and provide for existing and

emerging ocean uses.

NJ DEP

Monitor to identify and track pol-

lution sources impacting coastal

waters.

Bulkhead Water (Atlantic Ocean)

NJ DEP Division of

Land use Regulation

Oversees maintenance and

extension of bulkhead along

the Shrewsbury River. Bulk-

head construction and/or re-

construction within coastal

areas generally requires a

permit from NJDEP.

Private Property

Municipality

Sets codes, priorities, ordi-

Property owner, resident

Purchases NFIP insurance

nances to make changes to -

and ultimately streamline - NJ DEP Division of Land Use

bulkhead height and design Regulation

on Borough-owned property, Reviews permitting, sets impervious

encourages private landown- cover limits and vegetative cover per-

Parking/Sidewalk

ers to meet standards centages for developments within

through education Municipality

certain proximity to CAFRA (Coastal Trash collection, sidewalk

Area Facility Review Act) areas. Re- maintenance

sponsible for implementing USACE’s

proposed structure raisings. Private landowners

Landscaping, general

FEMA maintenance (owners)

Beach (Public Space)

Attaches requirements, i.e. raising

house, to recovery funding. Requires Roads USACE NJ Department of Health

purchase of NFIP insurance. Ongoing beach replenishment program, With NJDEP, sets Standard Operating

NJ DOT builds and maintains sacrificial beach Procedure for all recreational bathing

Municipality Permitting, funding. Designat- berm abutting seawall. beaches to ensure that the State, local

Zoning and land-use decision making. ed as coastal evacuation route. health authorities, municipalities, and

Writes building code, informed by all NJ DEP beach patrols are making every effort

NJ DEP Waterfront Restricts development in special areas

FEMA maps and including freeboard to remove debris and hazards from

of two feet, one foot higher than the Development such as beaches, riparian zones, flood

Permitting beaches and bathing areas.

state requirement. Orchestrates allot- hazard areas. Manages coastal area

ment of private and Community De- Municipality shore protection projects, including Municipality (DPW, Beach Patrol)

velopment Block Grant funding. Set forth plan for improved beach replenishment, participating with Orchestrates removal of debris, orga-

streetscape along Ocean US ACE on all Corps-sponsored protec- nizes training and stewardship when

Avenue, incorporating design tion projects. Organizes routine clean- beach profile undergoes significant

elements to increase resiliency ups and removal of larger debris, autho- change.

Sources: New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program. rizes permits to municipalities for beach

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. U.S. En- and dune maintenance and post-storm

vironmental Protection Agency. NJ Future. NJ Department restoration.

of Environmental Protection. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration. U.S. Fish Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 11

& Wildlife Service.

The Region’s Coastal

program to encourage greater flood protection measures

(beyond federal standards) through discounts on flood

Management Programs:

insurance rates for participating municipalities.

A Patchwork of

The ability for any municipality to be proactive around

adaptation, in large part, depends on its size and capac-

Coastal Regulation

ity to operate beyond day-to-day management. As a result,

larger cities with full time mayors and multiple staff are

better equipped to focus on adaptation and secure fund-

ing to carry out projects. For example, New York City has a

full-time Resilience Officer, a fully-staffed program focused

specifically on resilience and recovery and has resilience Connecticut

experts in other departments throughout the city’s agen-

cies. As a result, New York City is a national leader on adap- Enacted in 1980, the State of Connecticut’s Coastal

tation, with a long-range plan for resilience and multiple Management Program (CCMP) falls under the statu-

ongoing projects with full or partial funding. tory umbrella of Connecticut’s Coastal Management Act

(CCMA). The Program is administered and implemented

The vast majority of municipalities in our region, however by the Land and Water Resources Division, within the Con-

have volunteer or part-time leadership, with full time staff necticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protec-

focused largely on the essentials of ensuring a functioning tion (DEEP). Connecticut’s DEEP has regulatory juris-

community. Longer-term issues such as adaptation often diction over activity occurring in tidal wetlands and the

don’t rise to a priority level. Given this limited capacity, area waterward of the Coastal Jurisdiction Line, while an

local governments could benefit from a regional approach individual municipality holds jurisdiction over all activity

to coastal adaptation. that occurs within its municipal borders, landward of the

mean high water line of its coast. However, local planning

and zoning boards must frame plans under the guidance

of the CCMA. DEEP oversees, tracks, and shapes munici-

pal activity in the coastal zone through its ability to issue

development permits, review site plans for proposed land

developments and zoning changes, and comment on such

plans to ensure they are consistent with the state’s CMP.1

In spite of the state’s oversight abilities, municipalities are

not required to abide by DEEP’s comments. In this reality,

DEEP works to guide municipalities towards certain best

practices. However, if DEEP believes a community’s plan

contradicts the state’s coastal management program and

the community refuses to listen to DEEP’s recommenda-

tions, the state can legally appeal the municipality’s deci-

sion. This power, however, is not used frequently. Connecti-

cut’s program receives half of its funds from NOAA, with

the State government providing matching funds. In terms

of staff, the Program falls between New Jersey and New

York’s program in size, with approximately twenty-three

people.

1 “Connecticut Coastal Management Manual.” State of Connecticut Depart-

ment of Environmental Protection. September 2000. http://www.ct.gov/deep/

lib/deep/long_island_sound/coastal_management_manual/manual_08.pdf

12 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

New Jersey New York

The New Jersey Coastal Management Program, originally The New York State Coastal Management Program

recognized by NOAA in 1978, is managed by the New Jer- (NYSCMP) was created in 1982 by the New York Secretary

sey Department of Environmental Protection’s (NJDEP) of State, born from the 1981 Waterfront Revitalization of

Office of Coastal and Land Use Planning in DEP’s Land Coastal Areas and Inland Waterways Act (AKA: Executive

Use Management Division. Statutory authority for the Law, Article 42) and Chapter 464 of the 1975 Laws of New

state’s CMP comes from three major laws, which divide the York State. The New York State Department of State (DOS)

waterfront into three boundaries governed under different administers the State’s Coastal Management Program, and

rules: the Coastal Area Facility Review Act, which defined coordinates activities related to its implementation. 3 The

the CAFRA Zone; the Waterfront Development Law of NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC),

1914, which defined the Hackensack Meadowlands District; the agency tasked with protecting the State’s natural

and the Wetlands Act of 1970. New Jersey SEA (NJSEA) — resources, embeds the CMP’s policies into state practices

formerly the Meadowlands Commission — is the designated through its administrative authority for protecting coastal

CMP manager for the Hackensack Meadowlands area. 2 The erosion hazard areas; permitting authority for wetlands,

Coastal Management Program considers any municipality air quality, and water quality; and providing funding for

with tidally flowed waters to be within its planning region. various activities. Other state agencies, including the

Through NJDEP and NJSEA, the state regulates land and Department of Energy, the Public Service Commission,

water uses that may have significant impact on coastal and the Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preserva-

resources. tion, hold some responsibility for implementing the CMP’s

coastal policies, though the majority of Policies are carried

All waterfront development in New Jersey is regulated by out through the DEC’s regular programming. New York

the state. While development is subject to the local zon- State is unique in how it enables consistency between the

ing and building regulations of its respective municipal- state’s coastal communities and the federal government,

ity, public and private development projects are required while structuring it so individual coastal communities can

to obtain NJDEP permits. Furthermore, the state’s rules tailor it to fit their individual needs. The DOS encourages

supersede local zoning — meaning developers are obligated individual communities to prepare and implement a Local

to conform to state regulations in addition to local zoning. Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP). An LWRP is

If a municipality is in a specific coastal zone, it must follow a locally-prepared, comprehensive land and water use plan

the rules outlined by NJDEP. that provides a more detailed implementation of the State’s

CMP. By creating a LWRP, communities refine and tailor

The state’s Program is headed by the Office of Coastal and the State’s CMP policies to match their own unique needs

Land Use Planning, but it draws information and input and priorities. This holds a two-fold benefit, as the LWRP’s

from multiple DEP offices, including the Office of Policy inform the State government what each coastal community

Implementation, the Division of Land Use Regulation, and values, which then helps shape State policy. Once a com-

the Office of Dredging and Sediment Technology. Most of munity’s LWRP is approved by the NYSDOS and NOAA,

the Program’s work is done by its leading office, which has all State and Federal agencies’ actions occurring within the

four planners and approximately seven additional technical community’s coastal area must adhere to and be consistent

staff. The Office rarely coordinates with their counterparts with the LWRP.4

in New York and Connecticut — though they frequently col-

laborate with multi-state groups such as the NY/NJ Harbor New York also stands out from its neighbors in terms of the

Estuary Program, the Delaware Estuary, and MARCO, sheer size of its Program staff and budgetary sources. The

whose planning regions include portions of NJ. program has up to sixty staffers, and receives the majority

of its funding comes from the State, rather than the federal

Like Connecticut’s program, approximately half of the New government.

Jersey CMP’s funds are provided by NOAA, with the State

providing matching funds. However, the majority of New

Jersey’s resiliency work is supplied by NOAA’s annual grant

to the program.

3 “New York State Coastal Management Program and Final Environmental

Impact Statement.” New York State Department of State. Revised June 2017.

https://www.dos.ny.gov/opd/programs/pdfs/NY_CMP.pdf

2 State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Division of 4 “Local Waterfront Revitalization Program.” New York State Department

Land Use Regulation website. Accessed August 16, 2017. http://nj.gov/dep/lan- of State Office of Planning and Development. Accessed October 2017. https://

duse/coastal/cp_main.html www.dos.ny.gov/opd/programs/WFRevitalization/LWRP.html

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 13

A Vision for Regional Governance

and Dedicated Adaptation Funding

A Coastal Commission Commission Guidelines

for the Tri-State Region The final structure and governance of a Regional Coastal

Commission could take a number of forms, but should be

To fill the void in climate adaptation, New York, New guided by the best practices of other coastal commissions

Jersey and Connecticut should create a Regional Coastal and regional collaboratives (see more below) for maximum

Commission modeled after successful coastal commissions efficacy. The following represents a brief set of essential

in other regions. The region has several examples of com- guidelines for the development of a commission in the

missions and authorities that have coordinated municipal Region.

and private actions to preserve and manage environmental

assets, such as the Highlands and Meadowlands Commis- Be Inclusive and Cross-Jurisdictional

sions in New Jersey and the Pine Barrens Commission on Members of the commission should be designated across

Long Island. Other regions, including the San Francisco jurisdictions. Each of the three states should be repre-

Bay Area and the Chesapeake Bay region, have successful sented, as should each of the coastal counties. While the

region-scale coastal management authorities. A Regional sheer number of municipalities within the boundary would

Coastal Commission (RCC) would coordinate adaptation prevent complete participation, a representative number of

strategies undertaken by coastal communities, develop and municipal members should be designated. The structure

manage adaptation standards, and prioritize projects for should allow for free-flowing information between and

funding based on the potential for region-wide resilience. among all levels of government that have an interest and

Funding would come primarily from adaptation trust stake in adaptation decisions, even if they are not repre-

funds proposed in this report, but the commission could sented on the commission.

also prioritize projects funded from other federal and state

sources. Represent Different Coastal Conditions

The coast is not a monolithic place. Coastal place types

The mission of the Regional Coastal Commission will be to range from the highly developed urban shores of cities

advance adaptation planning and implementation across like New York, Jersey City and Bridgeport to the suburban

municipal and state boundaries to reduce the risks posed communities along the backbays and barrier beaches of

and expenses incurred by coastal flooding from storm Long Island and New Jersey to more natural settings like

surge, sea level rise and heavy precipitation in our region’s Long Island’s east end. The region’s estuary programs and

coastal communities, by: reserves could serve as useful frameworks for ensuring

representation from each of these different coast types.

⊲⊲ Producing a regional coastal adaptation plan that aligns

adaptation policies across boundaries and sets a vision Engage and Build Trust with Communities

for short- and long-term adaptation. The commission should ensure that community outreach

is an important part of its activities and mission, to ensure

⊲⊲ Developing and managing science-informed standards that all voices are heard and that trust is established

to guide projects and development/redevelopment in between the commission and communities.

the region’s flood-prone places.

Include Elected Officials

⊲⊲ Coordinating and encouraging collaborative projects Elected officials should have a role on the commission to

across municipal and state boundaries. give it legitimacy and visibility, but the governance struc-

ture must remain independent from political cycles and

⊲⊲ Evaluating and awarding funding for projects that align direct political interference.

with the standards established by the commission,

utilizing funds created by each state’s Adaptation Trust

Fund.

14 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

Engage Across Disciplines science and be flexible enough to change as conditions

Incorporating decisions and tools from the commission on the ground change. The commission will also play an

into other government agencies will be a key component of important role in communicating scientific information to

this collaborative. Both members and staff should include a government and community stakeholders.

variety of disciplines (environmental, development, trans-

portation, etc) to embed all aspects of adaptation planning Set Clear Criteria for Adaptation Funding

into decisions. One of the roles of the Coastal Commission would be to

oversee and make decisions about how Adaptation Trust

Be Informed by Science and Flexible to Changes Fund dollars are spent. The commission should ensure that

The rising seas and increasing intensity of storms will funding allocations and project selection is guided by a

dramatically alter the region’s coastline. It is important clear set of standards and evaluation metrics.

that the commission provide guidance based on the latest

Coastal Counties in the

NY-NJ-CT Region Vulnerable

to Sea Level Rise

Source: Regional Plan Association

Coastal County

Ulster

Dutchess

+1ft

Litchfield

+3ft Sea Level Rise

Sullivan

+6ft

New Haven

Putnam

Orange

NY

Fairfield

NJ

Westchester

NY

Sussex Rockland CT

Passaic

Bergen

Warren Morris Suffolk

Bronx

New

Essex York Nassau

Queens

Hudson

Union

Kings

Hunterdon

Richmond

Somerset

Middlesex

Regional Coastal Commission Coverage Area

Mercer

Monmouth In order to adequately plan for a future with increased flood-

ing from sea level rise along our coastlines, the commission’s

oversight area needs to extend beyond federal coastal zone

management boundaries of 1,000 feet beyond the shoreline.

We recommend the commission include each of the coastal

Ocean counties, municipalities that have land within the coastal

zone, plus any municipality with land at risk from flooding at

six feet of sea level rise. This second category would be a high

priority zone.This boundary could be periodically updated

by the commission to account for changes in sea level rise

projections and redrawn flood maps.

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 15

Why a Regional Coastal Commission?

The Institute for Sustainable Communities defines four Flexible by nature, regional collaboratives have a higher

classifications by which governance structures can be char- capacity to adapt to changing conditions, promote public

acterized.1 These categories gradually increase in formality participation, and enhance policy dialogue. As a result they

and decrease in flexibility. often emerge as an alternative to centralized institutions

that manage natural resources. 2 Over decades and across

⊲⊲ Informal Network: The least formal and most flexible the country, regional collaboratives have formed to man-

of these categories is an Informal Network, a group of age natural resources in large-scale, politically-complex

regional actors who agree to meet regularly to work environments.

together towards a shared goal. The New York Region

Climate Adaptation Network, recently launched by Successful regional governance structures focused on

RPA in partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land climate change adaptation can (1) coordinate action across

Policy, can be considered an informal network, as it multiple governments and sectors, creating a space to make

convenes professionals working on climate adaptation collective decisions and take action in a timely manner;

initiatives, uniting them by a shared goal but without an (2) reduce and resolve conflicts between stakeholders; and

official charter. (3) facilitate information and knowledge exchanges across

jurisdictional boundaries by pooling members’ funding,

⊲⊲ Chartered Network: A chartered network is a group of capacity, and communications. 3

people with a developed charter or system of agreed-

upon rules specifying how members wish to govern Climate adaptation initiatives are best implemented when

their interactions and make decisions. The Southeast they are embedded into the solutions of other issues, like

Florida Regional Climate Compact is considered a char- infrastructure upgrades or affordable housing, presenting

tered network, as members signed an official Compact an opportunity for climate adaptation solutions to simulta-

agreeing to a specific organization structure and means neously address issues like equity, affordability, and inclu-

of engagement in upon its formation. sivity, while also ensuring residents’ long-term well-being

in the face of climate change.

⊲⊲ Legal Entity: At the more formal end of the spectrum

is a Legal Entity, which has the ability to collect and Collectives have an advantage when applying for funds.

manage funding, hire staff, own assets, and enter into Access to federal funding or other large grants is easier

contracts. through an umbrella organization that covers multiple

political jurisdictions. County staff participating in the

⊲⊲ Regulatory Body: The most formal and least flexible of Southeast Florida Regional Climate Compact have been

the four entities, a Regulatory Body is granted authority able to leverage large pots of state and federal resources

to act as an arm of the government, and consequently because, as a collaborative working on climate change-

can levy taxes and fines, set regulations, or enact poli- related issues over a broad geography, the Compact is an

cies. attractive destination for funds coming into the region.4 It

has provided enough structure to help facilitate grants and

In its most basic definition, a regional collaborative is an technical assistance for the participating Counties, as well

entity where stakeholders representing an array of geog- as widen community access to federal and state support.

raphies, issues, and populations come together to identify

shared issues or goals, and work together to solve them

through a regional lens. Regional collaboratives can be

informal networks or regulatory agencies.

2 Tanya Heikkila and Andrea K Gerlak. “The Formation of Large-scale Col-

laborative Resource Management Institutions.” The Policy Studies Journal,

2005. Vol. 33, No. 4.

1 Adams S, Crowley M, Forinash C, and McKay H. “Regional Governance for 3 Institute for Sustainable Communities 2016.

Climate Action.” Institute for Sustainable Communities. 2016. 4 Institute for Sustainable Communities 2016.

16 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

Adaptation Trust Funds

Investments in adaptation projects for communities, The trust fund could be feasibly capitalized by a surcharge

habitats and infrastructure systems often come with a high on regulated property and casualty insurance premi-

price tag. Recent research from Zillow estimates that the ums statewide, and put into a public benefit corporation

region’s three states stand to lose $177.3 billion of housing authorized by each state.15 A research team from Harvard

stock (305,310 homes in total) to permanent flooding from University’s Graduate School of Design, commissioned by

six feet of sea level rise.14 And that’s just homes. Successful Regional Plan Association, looked at the unmet financial

adaptation investment models require a dedicated source needs identified in each state’s Community Development

of funding that is stable enough to utilize bond leverage. As Block Grant — Disaster Recovery amended Action Plans

federal funding for infrastructure, disasters and adapta- following Superstorm Sandy. They determined the rate

tion becomes less reliable, states are increasingly tasked of surcharge required to capitalize a trust fund and meet

with advancing innovative financing models that operate to these unmet needs over time. Without even utilizing lever-

address both a backlog of infrastructure investments and age in the bond market, the following estimated insurance

to prepare for climate change. RPA proposes the creation of surcharges for the average consumer were found to pay for

three Adaptation Trust Funds for NY, NJ and CT, funded the identified unmet needs of each state16:

by surcharges on insurance premiums. The funds would be

⊲⊲ Connecticut: $1/month

managed by each state as a public benefit corporation, with

underwriting and allocation decisions ultimately delegated ⊲⊲ New York: $5/month

to the Coastal Commission. However, each state could

⊲⊲ New Jersey: $15/month

independently create trust funds under this model with or

without the formal establishment of a coastal commission. In general, the range of surcharges necessary to capitalize

the trust funds are a small percentage (e.g., 0.5% to 1.5%)

of the premiums currently paid. New Jersey’s is consider-

ably higher because of the higher levels of identified unmet

needs in the state. Once capitalized, the trust funds could

support a range of potential project ranging from short-

term community resilience planning to long-term infra-

structure finance. A primary role of the Coastal Commis-

sion would be to establish the criteria by which projects

are prioritized and to determine allocations to projects

submitted for funding.

15 Keenan, J.M. (2017). Regional Resilience Trust Funds: An Exploratory

Analysis for the New York Metropolitan Region. New York, NY.: Regional Plan

Association.

14 NOAA, Zillow (via Zillow), 2017 16 Based on an annual insurance premium of $1,200.

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 17

Coastal resilience features can and should

be integrated into park design, so that

they are a both a community amenity and

a safety measure in severe storms.

Lower East Side Coastal

Resiliency Proposal

Source: Bjarke Ingels Group

18 Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017

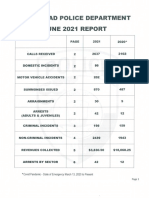

Sample Trust Fund Financed Projects

Funding

Mechanism Borrower Amount Project Project Description

Small grant State of New York, $500,000 Planning Study would include: a coastal area typology study; an inventory of potential

Department of Envi- Study strategies for existing green infrastructure; adaptive processes for science-

ronmental Conserva- informed decision-making in local jurisdictions; case studies of existing

tion adaptation projects; and education and outreach materials. The state agency

could leverage the grant with federal funding through the HUD Sustainable

Communities Regional Planning Grant.

Large grant New Jersey Sports $15,000,000 Brownfield Grant would offset eligible project costs for remediating toxic chemicals

and Exposition Remediation from land in the Meadowlands that is highly vulnerable to flooding and

Authority future inundation. In addition to cleanup, the grant would help support

adjacent site assessments, ecological adaptation strategies for local habits,

and community planning and training. In partnership with local jurisdictions

and property owners, the Authority would leverage funds from the U.S. EPA’s

Brownfield Grant Program and the NJ Hazardous Discharge Site Remedia-

tion Fund.

Large grant Norwalk Dept of $1,000,000 Green In- Project would develop programs to train municipal and county public works

Public Works / frastructure personnel to design and maintain green infrastructure that serves a dual

Stamford Office of Design and hazard mitigation purpose. Project funding could be leveraged from several

Operations Maintenance federal sources, including HUD’s Green Infrastructure and the Sustainable

Training Communities Initiative and the US EPA’s Clean Water Act Section 319 grant

program.

Concession Local Town, New $30,000,000 Managed Project is based on a program to help finance the relocation of low-to-

loan Jersey Housing Relo- moderate income households whose properties are in highly vulnerable to

cation Finance the risk of subsidence, storm surge and relative sea level rise. The program

Program would help finance the disposition of existing properties and the acquisi-

tion of in-land properties that were previously foreclosed. The net result is

that relocated households have a lower barrier to entry to in-land housing

markets and neighborhoods with previously foreclosed properties get an

injection of social and financial capital.

Concession GRID Alternatives $5,000,000 Photovoltaic Project would serve the co-benefits of climate mitigation, as well as the

loan (non-profit) (PV) Installa- benefits of increasing the passive survivability of facilities supporting highly

tion in Public vulnerable populations. With climate change, extreme heat and power

and Senior disruptions represent critical hazards for impacting human health. With an

Housing aging society, passive survivability is a potentially important part of commu-

nity resilience. In conjuncture with existing energy efficiency subsidies, this

concession loan provides the capital necessary to bring the levelized cost of

energy to within the means of financially strapped housing operators.

Prime rate Nassau County $100,000,000 Gap Loan for Project would provide the gap financing necessary to help the borrower

loan Department of Public Bay Park Wa- accommodate an $830 million renovation to the plant designed to mitigate

Works ter Reclama- and manage the risks associated with storm surge, increased deluge events,

tion Facility and sea level rise. In particular the loan would support the funding of: the up-

grading of power and back-up systems; the elevating of chemical tanks and

electrical controls; the installing of new pumping systems; and the develop-

ment of dual-purpose public spaces that promote the physical resiliency and

environmental sustainability of the adjacent neighborhood.

Prime rate Lower Manhattan $350,000,000 Infrastructure Project would provide supplemental efforts to the ongoing city led effort to

loan Property Cooperative Finance for fortify Lower Manhattan. The borrower is a non-profit cooperative corpora-

(non-profit) Multi-Purpose tion whose members are property owners, large tenants, Con Edison and

Flood Protec- the NYC EDC. As aging office buildings are replaced, this source of funding

tion helps finance coordinated lot and block improvements that synchronize with

the district level waterfront improvements. Eligible improvements include

those interventions in energy distribution, water management and public

space that contribute to the resilience of public and private operations in the

district.

Prime rate New Jersey Transit $100,000,000 NJ TransitGrid Project would provide additional financing for developing an innovative

loan micro-grid that accommodates a variety of extreme events from heat to

flooding. With an increasingly stressed and aging transit system, the project

seeks to increase reliability and reduce down time through the intelligent

management of distributed and renewable energy sources. Aside from the

core infrastructure improvements, the financing could support consumer

communications for re-routing when service is altered, as well as contingent

operations planning and operations redundancy for extreme events.

Source: Keenan, J.M. (2017). Regional Resilience Trust Funds: An Exploratory Analysis for the New York Metropolitan Region. New York, NY.: Regional Plan Associa-

tion. http://library.rpa.org/pdf/Keenan-Regional-Resilience-Trust-Funds-2017.pdf

Coastal Adaptation | Regional Plan Association | October 2017 19

Implementing a Regional Coastal

Commission: Best Practices

from Around the Country

Existing climate adaptation collaborative bodies are cal research on a regional scale, and to meet at an annual

incredibly diverse in terms of structure, size, jurisdiction, summit. Within a few months, these goals led the Compact

authority, scale, and scope of mission, illustrating that there to develop a regional preliminary inundation map, region-

is no prescribed format for such an entity (See Appendix). ally consistent sea level rise projections, and a regional

However, RPA’s review of existing regional collaborative baseline greenhouse gas emissions level. As the Compact

entities indicates there are several important factors vital accomplished its goals, it then pivoted its workload towards

to their success including: a shared long-term vision for capacity building in municipalities through resilience and

the entity; clear, distinct boundaries of jurisdiction; trust adaptation workshops for local government officials. The

between actors; and consistent information and data among way the Compact set clearly defined, achievable, focused

parties prior to the collaboration.17 To ensure the RCC’s goals early in its lifetime gave the collaborative the capac-

success, we identify best practices that inform the struc- ity to quickly unite county officials behind its agenda, and

ture and authority, collaboration and effectiveness, mem- gradually expand and update its responsibilities.

bership, data and information sharing, and funding of the

commission.

2 Involve elected officials

1 Begin with a clear and targeted while staying independent

mission, with the potential from election cycles.

to expand its mandate. Elected officials bring local expertise and the voices of their

constituents to the table. They can also help bring public

A clear, relatively narrow mission is essential for the suc- attention to the commission which is important espe-

cess of the commission. This will make it easier for orga- cially as it is starting to help build more political will and

nizers to design its governance structure, identify potential legitimacy to the body. Yet there is also need to embed the

participants, and foster the support to bring it to fruition. structure within existing government agencies to ensure

As it matures, the mandate can be expanded to tackle more that the work continues across administrations and is less

extensive issues as they arise, without losing sight of its influenced by politics. Incorporating decisions and tools

original mission. from RCC into other government agencies will be a key

component of this collaborative.

One example of this is how the Southeast Florida Regional

Climate Compact has evolved and expanded its mission. When the California Coastal Commission was created,

When it was founded in 2010, the Compact the signatories the Commission was an administrative body in Califor-

agreed upon was relatively simple, but broadly focused on nia’s executive branch and the State Legislature had the

one particular issue: coordinating climate change adapta- power to appoint and remove two thirds of the Commis-

tion initiatives. The signatory county governments agreed sion’s voting members at will. This made the Commission