Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Criminal Law: Murder

Uploaded by

Chris Boyle0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

142 views38 pagesPresentation on Murder for A Level Law.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPresentation on Murder for A Level Law.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

142 views38 pagesCriminal Law: Murder

Uploaded by

Chris BoylePresentation on Murder for A Level Law.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

You are on page 1of 38

Component 2: Criminal Law

(Offences against the Person) MURDER

Definition:

Lord Coke (a 17th century judge) defined murder

as ...

"the unlawful killing of a reasonable person in being

and under the Queen's peace with malice

aforethought, express or implied."

Actus reus:

"the unlawful killing of a reasonable person in being

and under the Queen's peace"

The actus reus of murder can be an act or an

omission but it must cause the death of the victim

(V).

Omissions

An omission is a failure to act.

The general rule is that an omission cannot satisfy

the actus reus of a crime.

But, an omission is able to satisfy the actus reus of

a crime if there is a duty to act.

A contractual duty:

Pittwood (1902)

A railway crossing keeper

failed to close the gates when

a train was due. V was

crossing the line, was hit by a

train and was killed.

The D's omission satisfied the

actus reus of manslaughter

because of his contractual

duty to act.

Duty through a relationship:

Gibbins and Proctor (1918)

G's daughter was deliberately

starved to death and both Ds

were convicted of murder.

G's omission was sufficient to

satisfy the actus reus of

murder because of his duty to

his daughter because of their

relationship.

A duty taken on voluntarily:

Stone and Dobinson (1977)

S's elderly sister came to stay

with the Ds and when she

became ill they failed to help

her or call for assistance.

The Ds' omission was enough

to satisfy the actus reus of

manslaughter because they

had taken on a duty

voluntarily.

Reasonable person in being

It means simply a "human being" ...

... and it raises 2 possible problems.

1. Is a foetus a "reasonable person in being"?

2. Is a V still alive and a "reasonable person in

being" if they are "brain-dead" but being kept

alive by a life-support machine.

Foetus

The killing of a foetus is not murder.

In order to be a human being a child must have an

"existence independent of the mother".

The child must be expelled from the mother's body

and have an independent circulation. The umbilical

cord does not need to be cut and the child need

not have taken it's first breath.

Attorney-General's reference

(No. 3 of 1994) (1997)

The HL stated that if a foetus

is injured and the child is then

born alive but later dies as a

result of the injuries then a

human being will have been

killed and can satisfy the

definition of murder.

Brain-dead

It is probable that a person who is "brain-dead"

would not be considered a "reasonable person in

being".

Doctors are allowed to switch off life-support

machines without being liable for murder

(Malcherek (1981)) ... the original attacker would

still be liable for the death.

Queen's peace

This simply means the killing of an enemy in the

course of war is not murder. But the killing of a

prisoner of war would be sufficient for the actus

reus of murder.

This is very unlikely to come up in the examination!

Causation

The prosecution must show that the D's conduct

was ...

1. The factual cause of the consequence; and

2. The legal cause of the consequence; and

3. There was no intervening act which broke the

chain of causation.

Factual cause

The D is only guilty if the consequence (V's death)

would not have happened "but for" the D's

conduct.

Pagett (1983)

The D used his pregnant

girlfriend as a human shield,

the D shot at armed police,

the police fired back and killed

the girlfriend.

The D was guilty of his

girlfriend's manslaughter. She

would not have been killed

"but for" the D's actions. D

was the factual cause of her

death.

White (1910)

The D put cyanide in his

mother's drink in order to kill

her. But she died of a heart

attack before the poison

could kill her.

"But for" D's actions she

would have died anyway and

therefore the D is not the

factual cause of his mother's

death.

Legal cause

The D's conduct must be more than a "minimal"

cause of the consequence but it doesn't need to

be a substantial cause.

Cato (1976)

The V prepared an injection of heroin

and water which the D then injected

into the V. The V died and the D was

convicted of manslaughter.

The CA stated ... "It was not

necessary for the prosecution to

prove that the heroin was the only

cause of death. As a matter of law,

it was sufficient if the prosecution

could establish that it was a cause,

provided it was a cause outside the

de minimus range, and effectively

bearing on the acceleration of the

moment of the V's death."

Kimsey (1996)

The CA held that instead of

using the term de minimus it

was acceptable to tell the jury

that there must be "more

than a slight or trifling link"

between the D's act and the

consequence.

So, the D can be guilty even

though his conduct was not

the only cause of death.

The thin skull rule

This rule states that the D must take the V as he

finds them.

If the V has something unusual about his physical

or mental state that makes him more susceptible

to injury, then the D will be liable for that injury even

if it is more serious than expected.

Blaue (1975)

V was stabbed by the D and

needed a blood transfusion to

save her life. The V refused

the blood transfusion because

she was a Jehovah's Witness,

and died. The D was still

guilty of murder because he

had to "take the V as he

found her", religious beliefs

and all.

Intervening acts

The chain of causation can be broken by:

1. The act of a 3rd party;

2. The V's own act;

3. A natural and unpredictable event.

In order to break the chain an intervening act

must be sufficiently independent of the D's

conduct and sufficiently serious enough.

If the D's conduct causes foreseeable action

by a 3rd party then the D is still likely to be held

to have caused the consequence (Pagett

(1983)).

Medical treatment

Medical treatment is unlikely to break the chain of

causation unless it is so independent of the D's act

and "in itself so potent in causing death" that

the D's acts are considered insignificant.

Smith (1959)

2 soldiers had a fight and one was

stabbed in the lung. The V was

carried to the medical centre and

was dropped twice on the way. At

the medical centre he was given

inappropriate treatment which

made the injury worse and he died.

Had he been given the correct

treatment V's chances of recovering

would have been as high as 75%.

But the original attacker was still

guilty of V's murder, the medical

treatment was not independent

enough of the D's act.

Cheshire (1991)

The D shot the V in the thigh and

stomach. V developed

breathing problems and was

given a tracheotomy. The V then

died from rare complications of

the tracheotomy which were not

spotted by the doctors. When V

died his original injuries were no

longer life threatening.

The D was still liable for V's

death, the medical treatment

was not independent enough of

the D's actions.

Jordan (1956)

the V had been stabbed in the

stomach, was treated and his

wounds were healing well. V was

then given an antibiotic but

suffered an allergic reaction. One

doctor stopped the use of the

antibiotic but the next day another

doctor ordered a large dose of the

antibiotic to be given to the V. V

died.

In this case the doctor's actions

were held to be an intervening act

that was sufficiently independent of

the D's action and it broke the

chain of causation.

Victim's own act

If the D causes the V to react in a foreseeable way,

then any injury suffered will be caused by the D.

Roberts (1971)

The V jumped from a car in

order to escape from the D's

sexual advances. V was

injured and the D was held

liable for her injuries.

It was considered foreseeable

that the V would react in this

way as a result of the D's

action.

If the V's reaction to the D's action is

unreasonable and unforeseeable then this may

break the chain of causation.

Williams (1992)

V (a hitch-hiker) jumped from D's

car and died from head injuries

caused by his head hitting the

road. The car was travelling at

approx. 30 mph. The

prosecution alleged the D had

attempted to steal V's wallet

causing him to jump from the

car.

The CA stated in order for D to

be liable the V must have acted

in a foreseeable way in

proportion to the threat. The V

didn't and the D was not liable.

Mens rea: malice aforethought

There are 2 ways in which the mens rea of murder

can be satisfied.

1. Express malice aforethought: the intention to

kill; or

2. Implied malice aforethought: the intention to

cause GBH.

So, a D can be guilty of murder even if they did

not have the intention to kill the V.

This was decided in the case of ...

Vickers (1957)

The D broke into the cellar of

a sweet shop and knew that

the old woman who owned it

was deaf. The old lady came

into the cellar and discovered

D. D hit her several times and

kicked her once in the head.

She died.

The CA upheld D's conviction

for murder. If a D intends

GBH and V dies then this has

always been sufficient to

imply malice aforethought.

Oblique intent

The main problem with proving intention is where

the D's main aim (direct intent) was not the death

of the V but something else. But in achieving the

main aim death is caused.

In these situations the D will not have the mens rea

for murder unless he foresaw that he would cause

death or GBH.

Moloney (1985)

The HL ruled that foresight

of consequences is only

evidence of intention.

Woollin (1998)

The HL stated that the jury are

n o t e n t i t l e d t o fi n d t h e

necessary intention unless

they are sure the death was a

virtual certainty as a result

of the D's action and that the

D appreciated this was the

case.

Matthews and

Alleyne (2003)

The CA stated that if a jury

decides D did foresee the

virtual certainty of death then

they are entitled to find

intention but they do not have

to do so ... because, as

Moloney states, foresight is

only evidence of intention.

You might also like

- Criminal Law: Involuntary Manslaughter: Unlawful Act ManslaughterDocument35 pagesCriminal Law: Involuntary Manslaughter: Unlawful Act ManslaughterChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Murder NotesDocument19 pagesMurder Notesapi-248690201No ratings yet

- Homicide - Actus ReusDocument6 pagesHomicide - Actus ReusKelly ObrienNo ratings yet

- Acts, Omissions, Causation, and Recklessness + Criminal Damage HandoutDocument9 pagesActs, Omissions, Causation, and Recklessness + Criminal Damage HandoutIshaanNo ratings yet

- Causation Essay ContentDocument4 pagesCausation Essay ContentSamina MehnajNo ratings yet

- Actus Reus and Causation (Summary) : The Physical ElementDocument15 pagesActus Reus and Causation (Summary) : The Physical ElementUsman JavaidNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - Homicide - Involuntary ManslaughterDocument7 pagesLecture 6 - Homicide - Involuntary ManslaughterCharlotte GunningNo ratings yet

- Homicide. Version 2023 24 1Document11 pagesHomicide. Version 2023 24 1sakiburrohman11No ratings yet

- Recap: Voluntary Manslaughter: Act and Section For DR AND For LCDocument25 pagesRecap: Voluntary Manslaughter: Act and Section For DR AND For LCTristan PaulNo ratings yet

- Homicide (Voluntary Manslaughter) W3Document6 pagesHomicide (Voluntary Manslaughter) W3sansarsainiNo ratings yet

- Crimiale HCGF BeDocument3 pagesCrimiale HCGF BenhsajibNo ratings yet

- Offences Relating To Human BodyDocument15 pagesOffences Relating To Human Bodysubhadeep aditya100% (1)

- Actus Reus 2012Document5 pagesActus Reus 2012Farhan TyeballyNo ratings yet

- Criminal Liability: IntentionDocument11 pagesCriminal Liability: IntentionSaffy CastelloNo ratings yet

- # 7 Criminal Homicide PDFDocument22 pages# 7 Criminal Homicide PDFDinesh Kannen KandiahNo ratings yet

- Law Entrance Exam Sample Paper 1Document7 pagesLaw Entrance Exam Sample Paper 1PriyaJindalNo ratings yet

- 1 - Relevant Rule of LawDocument6 pages1 - Relevant Rule of LawHualipo100% (1)

- Edward Snowden and The Emperor's Real ClothesFrom EverandEdward Snowden and The Emperor's Real ClothesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Law Revision Booklet Colour Ao2Document5 pagesLaw Revision Booklet Colour Ao2HadabNo ratings yet

- Actus Reus and Mens Rea of MurderDocument8 pagesActus Reus and Mens Rea of MurderJoshua AtkinsNo ratings yet

- Homicide (Murder) W3Document3 pagesHomicide (Murder) W3sansarsainiNo ratings yet

- All Criminal Law 2 Cases SummarizedDocument16 pagesAll Criminal Law 2 Cases Summarizedashleyramroop110No ratings yet

- 299 and 300 CRPCDocument11 pages299 and 300 CRPCAnshKukrejaNo ratings yet

- Actus Reus Causation Seminar Qs 2023-24 2Document4 pagesActus Reus Causation Seminar Qs 2023-24 2AminobutliketheacidNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Lecture 6 Homicide MurderDocument11 pagesCriminal Law Lecture 6 Homicide MurderVernon White100% (1)

- Final Assighnment 01Document4 pagesFinal Assighnment 01Saffah MohamedNo ratings yet

- Culpable Homicide Section 299 and 300 of IPCDocument8 pagesCulpable Homicide Section 299 and 300 of IPCdinoopmvNo ratings yet

- Watchmen Essay 1400 WordsDocument6 pagesWatchmen Essay 1400 Wordsapi-247836040No ratings yet

- Section 299 and 300 of IPCDocument8 pagesSection 299 and 300 of IPCYoyoNo ratings yet

- Murder + Invol. MS 2020Document13 pagesMurder + Invol. MS 2020Abdul Rahman ZAHOORNo ratings yet

- Crim Law OutlineDocument20 pagesCrim Law OutlineKimberly KoyeNo ratings yet

- MCQ AssessmentDocument10 pagesMCQ AssessmentTishah Vijaya KumarNo ratings yet

- Asesinos SerialesDocument14 pagesAsesinos SerialesAntonio MorentínNo ratings yet

- Culpable Homicide and Murder.Document6 pagesCulpable Homicide and Murder.Sathyanarayana Raju KNo ratings yet

- CausationDocument8 pagesCausationapi-234400353No ratings yet

- Criminal Law: Involuntary Manslaughter: Gross Negligence ManslaughterDocument17 pagesCriminal Law: Involuntary Manslaughter: Gross Negligence ManslaughterChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Murder IPC Notes in DetailDocument7 pagesMurder IPC Notes in DetailShubh Dixit100% (1)

- The Second American Revolutionary War for Independence: Book Ii of a Trilogy: the Indivisible LightFrom EverandThe Second American Revolutionary War for Independence: Book Ii of a Trilogy: the Indivisible LightNo ratings yet

- MurderDocument1 pageMurderTanzil Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Recap: Strict LiabilityDocument34 pagesRecap: Strict LiabilityTristan PaulNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Homocide RevisionDocument7 pagesCriminal Law Homocide RevisionlukeNo ratings yet

- Nfoap Handout 2011Document28 pagesNfoap Handout 2011Arefur Rahman Ray-AresNo ratings yet

- IPC SMPL July 2020 HomicideDocument11 pagesIPC SMPL July 2020 HomicideRashmiNo ratings yet

- Murder, Constructive Manslaughter, and Gross Negligence ManslaughterDocument3 pagesMurder, Constructive Manslaughter, and Gross Negligence Manslaughteraliferoz1272No ratings yet

- Criminal - Actus ReusDocument6 pagesCriminal - Actus Reussithhara17No ratings yet

- Offences Against Human Body Under Indian LawsDocument31 pagesOffences Against Human Body Under Indian LawsHEMALATHA SNo ratings yet

- Indian Penal Code (IPC) Section 300 For Murder - LatestLawsDocument9 pagesIndian Penal Code (IPC) Section 300 For Murder - LatestLawsmamiNo ratings yet

- Criminal HomicideDocument10 pagesCriminal Homicidesithhara17No ratings yet

- Short Quiz in Crim Law 1Document5 pagesShort Quiz in Crim Law 1John Turner0% (1)

- Causation in Criminal LawDocument12 pagesCausation in Criminal LawCliff Simataa100% (1)

- Ipc NotesDocument25 pagesIpc NoteskhuraltejNo ratings yet

- Question#4 Answer: Psychoanalytic TheoryDocument14 pagesQuestion#4 Answer: Psychoanalytic Theorymuneeba khanNo ratings yet

- Murder Physical Elements: Boughey V The Queen (1986)Document4 pagesMurder Physical Elements: Boughey V The Queen (1986)Anonymous 7jXAYq3No ratings yet

- Detailed Explanation To Culpable Homicide and Murder Section 299 and 300 IPC Class 3Document35 pagesDetailed Explanation To Culpable Homicide and Murder Section 299 and 300 IPC Class 3viren duggalNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 Model AnswersDocument21 pagesPaper 2 Model Answersminhal khanNo ratings yet

- Causation CasesDocument5 pagesCausation CasesRon Dublin-CollinsNo ratings yet

- LZ019: Law For University StudyDocument48 pagesLZ019: Law For University StudyShawn Johnson100% (3)

- 300 IpcDocument8 pages300 IpcMOUSOM ROYNo ratings yet

- LAW04: Criminal Law (Offences Against Property) : BurglaryDocument20 pagesLAW04: Criminal Law (Offences Against Property) : BurglaryChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Contract: OfferDocument27 pagesContract: OfferChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law: RobberyDocument23 pagesCriminal Law: RobberyChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law: TheftDocument71 pagesCriminal Law: TheftChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law: Non-Fatal Offences Against The PersonDocument52 pagesCriminal Law: Non-Fatal Offences Against The PersonChris Boyle100% (1)

- Criminal Law: Involuntary Manslaughter: Gross Negligence ManslaughterDocument17 pagesCriminal Law: Involuntary Manslaughter: Gross Negligence ManslaughterChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Tort: Occupiers' LiabilityDocument18 pagesTort: Occupiers' LiabilityChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Murder: Criticisms & ReformDocument17 pagesMurder: Criticisms & ReformChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law: Voluntary Manslaughter: Loss of ControlDocument25 pagesCriminal Law: Voluntary Manslaughter: Loss of ControlChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law: Voluntary Manslaughter: Diminished ResponsibilityDocument23 pagesCriminal Law: Voluntary Manslaughter: Diminished ResponsibilityChris BoyleNo ratings yet

- Never Talk To CopsDocument11 pagesNever Talk To CopscmonBULLSHITNo ratings yet

- Galvez Vs CADocument2 pagesGalvez Vs CADustin Gonzalez100% (1)

- E-T-, AXXX XXX 069 (BIA Sept. 13, 2017)Document10 pagesE-T-, AXXX XXX 069 (BIA Sept. 13, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Borlongan vs. PenaDocument7 pagesBorlongan vs. PenaWILHELMINA CUYUGANNo ratings yet

- Annexure-VII Declaration FormDocument3 pagesAnnexure-VII Declaration FormSoheli ParvinNo ratings yet

- SkdjksDocument4 pagesSkdjksBea Czarina NavarroNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Luke Paz ChargesDocument9 pagesJonathan Luke Paz ChargesCalebNo ratings yet

- FIA Act 1974 NotesDocument4 pagesFIA Act 1974 Notesbasharat ali shahNo ratings yet

- People V RellotaDocument24 pagesPeople V RellotaMauricio Isip CamposanoNo ratings yet

- For Foreigners Guide To Life and Law in KoreaDocument25 pagesFor Foreigners Guide To Life and Law in Koreaapi-26243979100% (2)

- Seminar 7 CausationDocument23 pagesSeminar 7 CausationAzizul KirosakiNo ratings yet

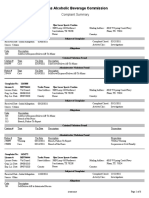

- Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission: Complaint SummaryDocument6 pagesTexas Alcoholic Beverage Commission: Complaint SummaryKENS 5No ratings yet

- Samala v. CADocument8 pagesSamala v. CAApril IsidroNo ratings yet

- OBLIGATIONS and CONTRACTSDocument134 pagesOBLIGATIONS and CONTRACTSJoshawn7 OmagapNo ratings yet

- Francisco v. CADocument2 pagesFrancisco v. CAMichelle Montenegro - AraujoNo ratings yet

- Crow v. Walsh Et Al - Document No. 3Document4 pagesCrow v. Walsh Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Act No. 4103 As Amended 1Document3 pagesAct No. 4103 As Amended 1jos aldrich bogbogNo ratings yet

- Violeta Bahilidad Vs People of ThephilippinesDocument2 pagesVioleta Bahilidad Vs People of ThephilippinesThessaloe B. Fernandez100% (1)

- United States v. Watkins, 10th Cir. (2007)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Watkins, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- II.A. Felonies - How Committed: Dolo 1Document10 pagesII.A. Felonies - How Committed: Dolo 1Quake G.No ratings yet

- Abang Lingkod V COMELEC DigestDocument1 pageAbang Lingkod V COMELEC DigestIc San Pedro50% (2)

- Abay v. PeopleDocument2 pagesAbay v. PeopleManuel Rodriguez IINo ratings yet

- GRUDA Application FormsDocument13 pagesGRUDA Application FormsBharat PatelNo ratings yet

- Cyber Crime QuestionsDocument3 pagesCyber Crime QuestionsDEBDEEP SINHANo ratings yet

- Intro To Law ReviewerDocument20 pagesIntro To Law ReviewerMces ChavezNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Waga vs. SacabiaDocument2 pagesHeirs of Waga vs. SacabiaMaya Julieta Catacutan-EstabilloNo ratings yet

- In Re Kay Villegas Kami Inc 35 SCRA 429 (1970)Document9 pagesIn Re Kay Villegas Kami Inc 35 SCRA 429 (1970)FranzMordeno100% (1)

- People of The Philippines vs. Eduardo Basin Javier, G.R. No. 130564, July 28, 1999Document1 pagePeople of The Philippines vs. Eduardo Basin Javier, G.R. No. 130564, July 28, 1999Cill TristanNo ratings yet

- 5 People Vs LiwanagDocument1 page5 People Vs LiwanagkarlNo ratings yet

- 003 Potenciana Evangelista v. People, G.R. Nos. 108135-36, 14 August 2000Document12 pages003 Potenciana Evangelista v. People, G.R. Nos. 108135-36, 14 August 2000John WickNo ratings yet