Professional Documents

Culture Documents

23 43 1 SM

Uploaded by

triOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

23 43 1 SM

Uploaded by

triCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Journal of Anesthesiology, 2017, 7, 400-406

http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojanes

ISSN Online: 2164-5558

ISSN Print: 2164-5531

Caudal Anesthesia: Experience in the

Post-Operative Analgesia in Pediatric

Ambulatory Surgery at the University

Hospital of Treichville

P. D. Ango1*, K. L. Kohou2, N. Koné1, A. Kouamé1, A. M. Y. Tchimou1, A. Akremy1, S. R. Bamkolé3,

N. Boua1, Y. Brouh4

1

Departmentof Resuscitation and Anesthesia, University Hospital Center of Treichville (CHUT), Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire

2

Department of Resuscitation and Anesthesia, Heart Institute Department of Abidjan (ICA), Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire

3

Pediatric Surgery Department, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire

4

Department of Resuscitation and Anesthesia, University Hospital Center of Cocody (CHUC), Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire

How to cite this paper: Ango, P.D., Abstract

Kohou, K.L., Koné, N., Kouamé, A.,

Tchimou, A.M.Y., Akremy, A., Bamkolé, Introduction: The caudal anesthesia is used by many authors for postoperative

S.R., Boua, N. and Brouh, Y. (2017) Caudal analgesia. The purpose of this study was to report our experience in the

Anesthesia: Experience in the Post-Opera-

practice of caudal block as post operative analgesia method in ambulatory

tive Analgesia in Pediatric Ambulatory

Surgery at the University Hospital of surgery in a context of limited technical equipment. Patients and Method:

Treichville. Open Journal of Anesthesiology, Over a period of 5 months, a prospective study was conducted on 39 children

7, 400-406. aged 3 to 5 years weighing on average 15.12 kg. Children classified ASA I and

https://doi.org/10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041

II were selected. After premedication with midazolam (0.3 mg/kg) by intra

Received: November 3, 2017 rectal route, the inhalation induction was made with sevoflurane 8%, conveyed

Accepted: December 25, 2017 by fresh gas (50% O2 and 50% air). The caudal block was obtained with the

Published: December 28, 2017

levobupivacaine 0.25% at a dose of 1 ml/kg. The hemodynamic parameters

Copyright © 2017 by authors and (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rates) and respiratory parameters

Scientific Research Publishing Inc. (respiratory frequency) pre-, per- and post-operative were measured. Post-

This work is licensed under the Creative operative pain was assessed with the Objective Pain Scale (OPS). The date of

Commons Attribution International

first use of analgesia was noted. The adverse effects of caudal block (meningitis,

License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ respiratory disorders, acute urinary retention, cardiac disorders) have been

Open Access assessed. Results: The average duration of the procedure was 55.2 minutes.

The use of analgesia was made 4 hours after skin closure, when the OPS

Broadmann score was greater than 3. An agitation was observed in 6 children.

Haemodynamic parameters have not significantly varied from the pre- to the

post-operative. No infectious complications or intolerance to local anesthetics

were observed. Allthe children were able to drink 4 hours after the end of the

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 Dec. 28, 2017 400 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

P. D. Ango et al.

intervention and issued their first urine later than 3 hours after surgery.

Conclusion: This type of anesthesia has been found very suitable for ambu-

latory surgery of the child, and is always helpful. It assured a post operative

analgesia of good quality, and a reduction in consumption of morphine

intraoperatively.

Keywords

Caudal Anesthesia, Postoperative Analgesia, Ambulatory Surgery, Children

1. Introduction

Caudal anesthesia finds its place in the per- and post-operative analgesia of

almost all interventions involving the lower abdomen and lower limbs; especially

in infants and young children [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]. It is safe and effective to receive

a sufficient period of analgesia, regardless of the type of surgery [6] [7] [8] [9]

[10]. This technique was the most used but nowadays it is increasingly neglected

in favor of Ultrasound guided peripheral blocks [11]. However, despite our

limited technical equipment, the caudal anesthesia is always practiced [1] [2].

The aim of our study was to report our experience of the practice of the caudal

block as a method of postoperative analgesia in ambulatory surgery in Abidjan.

2. Materials and Method

This is a prospective study conducted over a period of five months (From 1st

January to 31st May 2017). All the children were seen in pre-anesthesia

consultation, which made it possible to retain children of ASA I and II.

After obtaining informed consent from both parents (father and mother), 39

children aged 3 to 5 years were selected for a lower gastrointestinal and

urological surgery and removal of osteosynthesis material (Table 1). We

excluded all surgical emergencies, children with spina bifida or bleeding dis-

orders.

Table 1. Surgical indications.

Interventions Male (sex) Female n (%)

IH + Circumcision 15 (100) 0 (0)

Hernia of the ovary 0 (0) 6 (100)

Inguinal hernia 3 (100) 0 (0)

Removal of osteosynthesis

1 (33) 2 (67)

equipment

Testicular Ectopia 5 (100) 0 (0)

Umbilical hernia 2 (29) 5 (71.4)

Total 26 (67) 13 (33)

n = number, IH = inguinal hernia.

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 401 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

P. D. Ango et al.

The preoperative fast was 2 hours at least, the children drank apple juice (75

ml to 200 ml depending on the age) 2 hours before induction. The children were

admitted at 7 in the morning of surgery. We administered 0.3 ml/kg of

midazolam by intra rectal route half an hour before induction.

The inhalation induction was performed with 8% of sevoflurane, conveyed by

a mixture of fresh gases (50% oxygen and 50% Air) then the application of a

normal saline infusion according to 4-2-1 protocol adapted to the weight of each

child. Three micrograms per kg of fentanyl were injected through directly

intravenous use.

Propofol was injected at a dose of 2 milligram (mg) per kg to complete the

inhalation induction. All the children were intubated and put on a respirator,

after the eyes were well centered and fixed.

After induction, the concentration of sevoflurane was reduced to 2%. The

children were placed in left lateral decubitus; thighs bent over the pelvis. We

spotted the sacral hiatus and a skin aseptic techniquewas performed. only 1 ml of

test dose of lidocaine adrenaline in the sacral canal has been injected. One

minute later, a single dose of 1 ml/kg according to the scheme of Armitage, not

exceeding 20 ml of levobupivacaine 0.25% was injected at an angle of 40˚ to 60˚.

Aspiration tests during injection are performed frequently. The needle is

removed once the injection is completed and the child is placed in a supine

position after a local dressing. A Tuohy needle (short bevel 24 - 24 g) for caudal

anesthesia was used for injection into the sacral canal.

The following parameters were measured using a monitor: Non-invasive

systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean blood

pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR) and respiratory rate (RR) during pre, per and

post operative period.

In the recovery room, the post operative pain was evaluated with the Objective

Pain Scale (OPS) of Broadmann, every 30 min, until the exit of the patient. A

score greater than 3allowed the use of injectable paracetamol at the dose of 15

mg/kg with or without ibuprofen (7.5 mg/kg). The duration of the motor block

was also evaluated. Children were reviewed on the third day, then a week later to

search neuro meningeal complications.

The data were collected using an individual survey form. Data entry and data

analysis were done using Epi Info 7.1. The analysis was made with the Statiscal

Package for Social Sciences 8. The parameters are expressed in mean ± standard

deviation (extreme value). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

Of the 39 children, there were 13 girls and 26 boys.

The average age was 3.9 ± 0.7 (3 to 5.4) years. The average weight was 15.12 ±

3.4 kg. The average duration of surgery was 55.2 ± 14.5 minutes. The

surgicalindications are shown in Table 1. Hemodynamic parameters pre, per,

and postoperative are shown in Table 2. Until the release of the hospital,

postoperative pain score was evaluated and shown in Table 3. A rescue analgesia

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 402 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

P. D. Ango et al.

Table 2. Hemodynamic parameters.

Pre anesthesia Per anesthesia Post anesthesia probability

91.6 ± 6.3 89.1 ± 6.1 92.9 ± 5.5

SBP (mmHg) NS

(81 - 105) (79 - 99) (79 - 102)

39.3 ± 3.8 42.4 ± 2.9 38.9 ± 2.2

DBP (mmHg) NS

(31 - 48) (37 - 47) (32 - 43)

39.1 ± 2.4 59.9 ± 2.04 39.5 ± 3.16

MBP en mmHg NS

(32 - 45) (55 - 65) (33 - 45)

101 ± 10.6 100 ± 2.4 92.01 ± 12.3

HR (beats/min) NS

(92 - 119) (87 - 104) (86 - 123)

20.16 ± 3.9 21.05 ± 2.14 22 ± 2.3

RR (cycle/min) NS

(18 - 27) (19 - 26) (17 - 24)

Results = mean ± standard deviation (minimum-maximum). NS = Not significant difference (p < 0.05).

Table 3. Average of post anesthesia OPS (Objective Pain Scale).

Time in hour T1 T2 T3 T4 T5

OPS 1.36 ± 0.48 2.48 ± 0.5 3 ± 00 3.46 ± 0.5 0.61 ± 0.54

Results = average ± standard deviation (minimum-maximum). T1 = 2 hours 30 minutes ; T2 = 3 hours ; T3

= 3 hours 30 minutes ; T4 = 4 hours; T5 = 4 hours 30 minutes.

was performed 4 hours after skin closure. The average duration of motor

blockwas 2.82 ± 0.43 hours. No intravascular injection was observed. Fentanyl

was not reinjected intraoperatively. Six (6) children presented a emergence

agitation, two after the 15th minute and another 4 after the 30th minute of the

skin closure. The taking of liquid feeding occurred 4 hours after surgery. No

infectious complications were noted. The hemodynamic and respiratory para-

meters have not been modified. All children are issued their first urine before the

4th hour before leaving the hospital.

4. Discussion

Limitation of the Study

The cost of the equipment (Tuohy needle and levobupivacaine) was at the

charge of patients (who did not have health insurance), which was a limit to the

choice of this practice and thus explained the small size of our study population.

In this study, the caudal anesthesia has allowed an effective post-operative

analgesia in the child having receivedan ambulatory surgery. It is interesting and

easy to perform [5] [8] [11] [12]. The addition of an adrenalineprolongs the

duration of the analgesia and permits to quickly detect an intravascular injection

of local anesthetic. This accident of the intravascular injection was not found in

this study.

Once little practiced, peripheral blocks represent nowadays the regional

techniques most used in many surgical indications in children [11].

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 403 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

P. D. Ango et al.

They are performed by single injection or continuous infusion using a fixed

catheter [11] [12]. This new trend is explained by the fact that the caudal block

(formerly more used) has a high morbidity: accidental intraspinal and intra-

vascular injections of local anesthetic. The use of ultrasound in the peripheral

blocks offers a safety and a clear cut efficiency: permanent visual control of the

needle and the diffusion of the local anesthetic, control of the volume of the

injected dose [13] [14].

The principle of the caudal anesthesia is based on the fact that the sacral

hiatus opens directly on the sacral canal representing the caudal end of the

spinal canal. The latter contains the latest spinal roots forming the cauda equina

and the filum terminal.

Levobupivacaine is widely used clinically in caudal and spinal anesthesia [2, 4]

to manage acute and chronic pain. It acts on pain by inhibiting the activity of

NMDA receptors (N Methyl D Aspartate) in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord

[16]. It blocks the sodium channels and decreases their secretions. It would

accelerate the disintegration of synaptic currents NMDA receptor at the normal

synaptic transmission [15]. These effects have permited us to obtain a period of

long action, allowing an adequate postoperative analgesia [16] [17]. The caudal

anesthesia was used as a method of postoperative analgesia by many authors [1]

[4] [15] [17] without major hemodynamic and respiratory changes [17]. this

technique can also be interesting, in emergency,in the treatment of strangled

inguinal hernia or testicular torsion [5] [10].

The Midazolam used in premedication has reduced plasma levels of local

anesthetic in the children [9]. This decrease in plasma levels could explain the

absence of intolerance manifestation vis-à-vis the local anesthetics in children.

The use of midazolam in premedication has also reduced the incidence of the

onset of the emergence delirium. These agitations are frequently observed

during the use of sevoflurane in anesthesia in the child [18] [19].

Sevoflurane replaced halothane in pediatric anesthesia for safety reasons: a

favorable cardiovascular profile, Cardiac index drops significantly with halothane

compared to the use of sevoflurane [20]; a large decrease in myocardial con-

tractility of the newborn by a decline speed attachment-detachment from

actin-myosin bridges of heart muscle [21]. The Sevoflurane is an alternative in

patients at high risk: difficult intubation, asthmatic patients and allergic patients

[22].

The oral liquid started early in all our patients [16] [17]. This is an interesting

technique for ambulatory surgery.

5. Conclusion

This study has shown us that the caudal anesthesia provides comfort and safety

for patients. This technique has to be developed more, in an effort to expand its

indications in the sub umbilical surgery. Indeed in Côte d’Ivoire peripheral

blocks are underdeveloped, difficult to favour for unsufficiency of technical

equipment (ultrasound for localization of nerves).

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 404 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

P. D. Ango et al.

References

[1] Aguemon, A.R., Agbonon, H., Atchadé, D., Hounnou, G., Koura, A., Diallo, A.T., et

al. (1998) Anesthésie caudale chez l’enfant noir: Faisabilité et tolérance. Cahiers

D’Anesthesiologie, 46, 239-243.

[2] Dressen, A.J., Zepka, A.L., Ehounound, M. and N’dri, D. (1991) Anesthésie caudale:

Expérience du CHU de Treichville à propos de 50 cas. Publ. Med Afr, 7-10.

[3] Kim, E.M., Lee, J.R., Koo, B.N., Im, Y.J., Oh, H.J. and Lee, J.H. (2014) Analgesic

Efficacy of Caudal Dexamethasone Combined with Ropivacaine in Children

Undergoing Orchiopexy. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 112, 885-891.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aet484

[4] Ivani, G., De Negri, P., Lonnqvist, P.A., Eksborg, S., Mossetti, V., Grossetti, R.,

Italiano, S., Rosso, F., Tonetti, F. and Codipietro, L. (2003) A Comparison of Three

Different Concentrations of Levobupivacaine for Caudal Block in Children.

Anesthesia & Analgesia, 97, 368-371.

https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000068881.01031.09

[5] Astuto, M., Disma, N. and Arena, C. (2003) Levobupivacaine 0.25% Compared with

Ropivacaine 0.25% by the Caudal Route in Children. European Journal of

Anaesthesiology, 20, 826-830. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003643-200310000-00009

[6] Locatelli, B., Ingelmo, P., Sonzogni, V., Zanella, A., Gatti, V., Spotti, A., Di Marco,

S. and Fumagalli, R. (2005) Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III, Controlled Trial

Comparing Levobupivacaine 0.25%, Ropivacaine 0.25% and Bupivacaine 0.25% by

the Caudal Route in Children. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 94, 366-371.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aei059

[7] Cinar, S.O., Isil, C.T., Sahin, S.H. and Paksoy, I. (2015) Caudal Ropivacaine and

Bupivacaine for Postoperative Analgesia in Infants Undergoing Lower Abdominal

Surgery. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 31, 903-908.

[8] Giaufre, E. (1990) Anesthésie caudale par injection unique. In: Schult Steinber, O.

and Saint Maurice, C., Eds., Anesthésie loco Régionale en Pédiatrie, Arnette, Paris,

81-87.

[9] Giaufre, E., Bruguerolle, B., et al. (1990) The Influence of Midazolam on the Plasma

Concentrations of bupivacaine after Caudal Injection of the Mixture of the Local

Anesthetics in Children. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 34, 44-46.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1990.tb03039.x

[10] Meignier, M., Babin, M. and Souron, R. (1982) Anesthésie caudale chez le nourrisson

et le petit enfant. Annales Françaises d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation, 635-638.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0750-7658(82)80107-X

[11] Ecoffey, C., Lacroix, F., Giaufré, E., Orliaguet, G. and Courrèges, P. (2010)

Association des Anesthésistes Réanimateurs Pédiatriques d'Expression Française

(ADARPEF) Epidemiology and Morbidity of Regional Anesthesia in Children: A

Follow-Up One-Year Prospective Survey of the French-Language Society of Pae-

diatric Anaesthesiologists (ADARPEF). Pediatric Anesthesia, 20, 1061-1069.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03448.x

[12] Lacroix, F..(2008) Epidemiology and Morbidity of Regional Anaesthesia in Child-

ren. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology, 21, 345-349.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282ffabc5

[13] Willschke, H., Marhofer, P., Bösenberg, A., Johnston, S., Wanzel, O., Cox, S.G.,

Sitzwohl, C. and Kapral, S. (2005) Ultrasonography for Ilioinguinal/Iliohypogastric

Nerve Blocks in Children. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 95, 226-230.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aei157

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 405 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

P. D. Ango et al.

[14] Weintraud, M., Marhofer, P., Bösenberg, A., Kapral, S., Willschke, H., Felfernig, M.

and Kettner, S. (2008) Ilioinguinal/Iliohypogastric Blocks in Children: Where Do

We Administer the Local Anesthetic without Direct Visualization? Anesthesia &

Analgesia, 106, 89-93. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000287679.48530.5f

[15] Constant, I., Gall, O., Gouyet, L., Chauvin, M. and Murat, I. (1998) Addition of

Clonidine or Fentanyl to Local Anaesthetics Prolongs the Duration of Surgical

Analgesia after Single Shot Caudal Block in Children. British Journal of Anaesthesia,

80, 294-298. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/80.3.294

[16] Paganelli, M.A. and Popescu, G.K. (2015) Actions of Bupivacaine, a Wideley Used

Local Anesthetic, on NMDA Receptor Responses. Journal of Neuroscience, 35,

831-842. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3578-14.2015

[17] Moine, P. and Ecoffey, C. (1992) Caudal Block in Children: Analgesia and

Respiratory Effect of the Combination Bupivacaine-Fentanyl. Annales Françaises

d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation, 11, 141-144.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0750-7658(05)80004-8

[18] Ozcan, A., Kaya, A.G., Ozcan, N., Karaaslan, G.M., Er, E., Baltaci, B. and Basar, H.

(2014) Effects of Ketamine and Midazolam on Emergence Agitation after

Sevoflurane Anaesthesia in Children Receiving Caudal Block: A Randomized Trial.

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology, 64, 377-381.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2014.01.004

[19] Köner, O., Türe, H., Mercan, A., Menda, F. and Sözübir, S. (2011) Effects of

Hydroxyzine-Midazolampremedication on Sevoflurane-Induced Paediatric Emer-

gence Agitation: A Prospective Randomised Clinical Trial. European Journal of

Anaesthesiology, 28, 640-645. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e328344db1a

[20] Wodey, E., Pladys, P., Copin, C., Lucas, M.M., Chaumont, A., Carre, P., Lelong, B.,

Azzis, O. and Ecoffey, C. (1997) Comparative Hemodynamic Depression of

Sevoflurane versus Halothane in Infants: An Echocardiographic Study. Anesthe-

siology, 87, 795-800.

[21] Prakash, Y.S., Cody, M.J., Hannon, J.D., Housmans, P.R. and Sieck, G.C. (2000)

Comparaison of Volatile Anesthetic Effects on Actin-Myosin Cross-Bridge Cycling

in Neonal Versus Adult Cardiac Muscle. Anesthesiology, 92, 1114-1125.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200004000-00030

[22] Bishop, M.J. and Rooke, G.A. (2000) Sevoflurane for Patients with Asthma.

Anesthesia & Analgesia, 91, 245-246.

https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-200007000-00050

DOI: 10.4236/ojanes.2017.712041 406 Open Journal of Anesthesiology

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Mpac Sept2016 World Malaria ReportDocument19 pagesMpac Sept2016 World Malaria ReporttriNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Current Management and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: ReviewDocument5 pagesCurrent Management and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: ReviewtriNo ratings yet

- 452 883 1 SM PDFDocument7 pages452 883 1 SM PDFsri marianaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 1-Wayan Getas-Juni 2012 PDFDocument6 pages1-Wayan Getas-Juni 2012 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- MWJ2016 7 3Document6 pagesMWJ2016 7 3triNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Global Vector Control Response 2017-2030: Fourth Draft (Version 4.3)Document50 pagesGlobal Vector Control Response 2017-2030: Fourth Draft (Version 4.3)Febby WadoeNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Saillant 2019Document9 pagesSaillant 2019triNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Micheletti2018 PDFDocument67 pagesMicheletti2018 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- C2eek635 BYCDocument65 pagesC2eek635 BYCtriNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Risk Perception Regarding Drug Use in PregnancyDocument4 pagesRisk Perception Regarding Drug Use in PregnancytriNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Micheletti2018 PDFDocument67 pagesMicheletti2018 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- 1 s2.0 S0002937819307069 Main PDFDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0002937819307069 Main PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Host-Seeking Activity of A Tanzanian Population of Anopheles Arabiensis at An Insecticide Treated Bed NetDocument14 pagesHost-Seeking Activity of A Tanzanian Population of Anopheles Arabiensis at An Insecticide Treated Bed NettriNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Saillant 2019Document9 pagesSaillant 2019triNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Stroumsa 2019Document4 pagesStroumsa 2019triNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 97165673-f831-4abe-a55b-dd9862e49200Document5 pages97165673-f831-4abe-a55b-dd9862e49200triNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Bogani Et Al-2019-International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics PDFDocument5 pagesBogani Et Al-2019-International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics PDFtriNo ratings yet

- 97165673-f831-4abe-a55b-dd9862e49200Document5 pages97165673-f831-4abe-a55b-dd9862e49200triNo ratings yet

- Anatomical and Pathophysiological Classification of Congenital Heart DiseaseDocument16 pagesAnatomical and Pathophysiological Classification of Congenital Heart DiseasePietro PensoNo ratings yet

- Saillant 2019Document9 pagesSaillant 2019triNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937819307069 Main PDFDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0002937819307069 Main PDFtriNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Bogani Et Al-2019-International Journal of Gynecology & ObstetricsDocument5 pagesBogani Et Al-2019-International Journal of Gynecology & ObstetricstriNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937819306817 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0002937819306817 MaintriNo ratings yet

- E81 FullDocument112 pagesE81 FulltriNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Stroumsa 2019Document4 pagesStroumsa 2019triNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S107476131500179X MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S107476131500179X MaintriNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937819307069 Main PDFDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0002937819307069 Main PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Menopausal Symptoms and Surgical Complications After Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy, A Register-Based Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesMenopausal Symptoms and Surgical Complications After Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy, A Register-Based Cohort StudytriNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- 1 s2.0 S107476131500179X MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S107476131500179X MaintriNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002937819306817 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0002937819306817 MaintriNo ratings yet

- Indications of General Anaesthesia in Dentistry 3Document2 pagesIndications of General Anaesthesia in Dentistry 3NaseemNo ratings yet

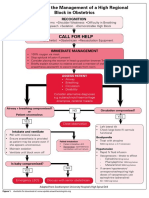

- Algorithm For The Management of A High Regional Block in ObstetricsDocument5 pagesAlgorithm For The Management of A High Regional Block in ObstetricsRaditya DidotNo ratings yet

- NailSurgery With Name ChangesDocument55 pagesNailSurgery With Name ChangesIde Bagoes InsaniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading Rizki Widya Kirana - 03012236Document15 pagesJurnal Reading Rizki Widya Kirana - 03012236R Widya KiranaNo ratings yet

- Endodontics Pain Control in Endodontics: Differential Diagnosis of Dental PainDocument4 pagesEndodontics Pain Control in Endodontics: Differential Diagnosis of Dental Painريام الموسويNo ratings yet

- Medical EmergenciesDocument115 pagesMedical EmergenciesRamya ReddyNo ratings yet

- Geriatrics Quiz 10 QuestionsDocument2 pagesGeriatrics Quiz 10 QuestionsBrian Strauss100% (4)

- La Management of Special PtientDocument27 pagesLa Management of Special PtientIyad Abou-RabiiNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology: General Anaesthetic AgentsDocument65 pagesPharmacology: General Anaesthetic AgentsSharifa DarayanNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Dental Anestesi Jurnal 2Document2 pagesDental Anestesi Jurnal 2Indira NoormaliyaNo ratings yet

- Rocuronium: Bromide InjectionDocument2 pagesRocuronium: Bromide InjectionNursalfarinah BasirNo ratings yet

- PharmacologyDocument236 pagesPharmacologynbde2100% (5)

- Recommendations To Use Vasoconstrictors in Dentistry and Oral SurgeryDocument30 pagesRecommendations To Use Vasoconstrictors in Dentistry and Oral SurgeryAnonymous i7fNNiRqh2No ratings yet

- Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity AlgorithmDocument1 pageLocal Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity AlgorithmSydney JenningsNo ratings yet

- Bedah Buku InstrumenDocument12 pagesBedah Buku Instrumencoffe latteNo ratings yet

- DR - Vinay Jain PG1 YearDocument76 pagesDR - Vinay Jain PG1 YearNeelesh BhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Sural Nerve BiopsyDocument2 pagesSural Nerve BiopsyArindam MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- MCQs LADocument29 pagesMCQs LAPadmavathi C100% (1)

- Pharma MCQDocument0 pagesPharma MCQFoysal Sirazee0% (2)

- Spinal and Epidural Anesthesia: Jedarlyn G. Erardo, RPH, MDDocument101 pagesSpinal and Epidural Anesthesia: Jedarlyn G. Erardo, RPH, MDjedarlynNo ratings yet

- Caesarean in Mare by Marcenac Incision Under Local AnaesthesiaDocument3 pagesCaesarean in Mare by Marcenac Incision Under Local AnaesthesiaDanielaNo ratings yet

- Buffered Anaesthetic S: DR Shazeena QaiserDocument25 pagesBuffered Anaesthetic S: DR Shazeena QaiserShazeena OfficialNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Nursing - OrIGINALDocument176 pagesPerioperative Nursing - OrIGINALJamil Lorca100% (4)

- Hialuronidasa en Bloqueo AxilarDocument8 pagesHialuronidasa en Bloqueo Axilarantonio123valenciaNo ratings yet

- Anesthetics - They Decrease Afferent Nerves Sensibility B.astringent, C.covering, D.adsorbingDocument4 pagesAnesthetics - They Decrease Afferent Nerves Sensibility B.astringent, C.covering, D.adsorbingAnjaliNo ratings yet

- Meralgia ParestheticaDocument22 pagesMeralgia ParestheticaWahyu Tri KusprasetyoNo ratings yet

- Local Anesthetics: Ms. Sneha J. SawantDocument11 pagesLocal Anesthetics: Ms. Sneha J. Sawantrushikesh ugaleNo ratings yet

- Local AnestheticsDocument47 pagesLocal AnestheticsKeerthi LakshmiNo ratings yet

- Use This File If Printing The Whole WorkbookDocument819 pagesUse This File If Printing The Whole WorkbookAndrewNo ratings yet

- Saddle BlockDocument3 pagesSaddle BlockVasu DevanNo ratings yet

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)