Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lesson 4 Morphology and Syntax Morphology Deals With The Internal Structure of Words. Words Are Made Up of Morphemes But

Uploaded by

Paula PepeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lesson 4 Morphology and Syntax Morphology Deals With The Internal Structure of Words. Words Are Made Up of Morphemes But

Uploaded by

Paula PepeCopyright:

Available Formats

Grammar I Graciela Palacio

LV/JVG 2015

LESSON 4

MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX

Morphology deals with the internal structure of words. Words are made up of morphemes but

they are not simple sequences of morphemes. They have internal structure and their internal

structure is rule-governed and hierarchical.

Derivational morphemes select the root that they can attach to. For example, -able is a bound

derivational morpheme which gets attached to verbs. So when –able selects the verb read we get

readable, whose structure can be represented by means of the following tree diagram:

The prefix un- with a negative meaning gets attached to adjectives (happy/unhappy). So if un-

selects readable, an adjective, we get unreadable, another adjective, whose structure can be

represented in the following way:

The word unsystematic is composed of three morphemes: un-, system, and –atic. The root is

system, a noun. Now system combines first with –atic, forming the adjective systematic. The

negative prefix un- combines with the adjective systematic to form another adjective with a

negative meaning.

Page 1 of 4/Lesson 3’ Morphology & Syntax

The root system is closer to –atic than it is to un-, and un- is connected to the adjective

systematic, and not directly to system. *unsystem is not a word because there is no rule of

English that allows un- to be added to nouns. The tree diagram for unsystematic is as follows:

There is in English another prefix un- which means “to reverse action”. While negative un-

attaches to adjectives, reversative un- attaches to verbs as in:

load/ unload the truck; button/ unbutton a shirt; zip /unzip a dress.

The tree in this case would be as follows:

The hierarchical organization of words is more clearly seen in the case of structurally ambiguous

words, i.e. words that have more than one meaning by virtue of having more than one structure.

Consider, for example, the word unlockable. Imagine you are inside a room and you want some

privacy. You would be unhappy to find that the door is unlockable – “not able to be locked.” -

able combines with lock, to form the adjective lockable (“able to be locked”). Then the prefix

un-, meaning “not,” combines with the derived adjective to form a new adjective unlockable

(“not able to be locked”). This meaning of the word unlockable would correspond to the

following tree diagram:

Page 2 of 4/Lesson 3’ Morphology & Syntax

Now imagine you are inside a locked room trying to get out. You would be very relieved to find

that the door is unlockable – “able to be unlocked.” – from the inside. In this case, the prefix un-

combines with the verb lock to form a derived verb unlock. Then, the derived verb combines

with the suffix –able to form unlockable, “able to be unlocked.” This meaning corresponds to the

following structure:

Other words that follow this pattern would be unbuttonable and unzippable, among others.

Structure is important to determine meaning. The different meanings arise because of the

different structures. Hierarchical structure is an essential property of human language.

Inflectional vs Derivational Morphemes

Radford (1999: 168) makes us notice that, as they determine the category of a word, derivational

morphemes tend to appear before inflectional morphemes. For example, from the verb paint we

can derive the agentive noun painter, whose plural will be paint-er-s and not *paint-s-er.

Morphemes vs Syllables

Jackendoff (1997) notes that while in morphology we work with the notion of morpheme, in

phonology we work with the notion of syllable. Syllables and morphemes are not in a one to one

correspondence. For example, from a morphological perspective the word organization is

derived from the word organ1 (a free morpheme) through the addition of two bound morphemes

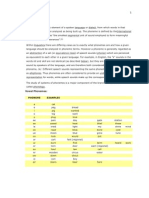

–iz(e) and –ation:

1

organ: a fully differentiated structural and functional unit

Page 3 of 4/Lesson 3’ Morphology & Syntax

[ [ [organ] iz] ation]

However, from a phonological point of view, the word is made up of segments, five syllables (or

+ ga + ni + za + tion) and two feet [or + ga + ni] [za + tion], a foot being a group of two or more

syllables in which one syllable has the major stress.

Syllables are not morphemes. While morphemes are lexical or syntactic entities, segments,

syllables and feet are phonological entities which cut across morpheme boundary.

SYNTAX

Syntax deals with the way elements combine to form more complex structures. In the same way

as words are not simple sequences of morphemes, sentences are not strings of words. Sentences

are also hierarchically structured. Carnie (2011: 6) clearly explains the difference between

simple addition and syntax. He claims that if you add up the values of a series of numbers, it

doesn’t matter what order they are added in:

7 + 8 + 15 + 2 = 2 + 15 + 8 + 7 = 8 + 7 + 2 + 15

But if you combine the following words yellow, singing, the, a, elephant, mouse, sniffed in

different ways you get different sentences which do not mean the same (e.g. A singing elephant

sniffed the yellow mouse, The yellow elephant sniffed a singing mouse, etc.). The structure of

sentences can be represented in different ways: by means of tree structures, by means of

bracketing or by means of boxes.

Lesson 3 Activity 1: (to be handed in as assignment 3)

Draw the tree for the following words:

1. employers

2. employees

3. unhappiness

4. careful

5. unconventional

References

Fromkin, V., R. Rodman & N. Hyams (2011: 9th ed.) An Introduction to Language. USA:

Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. (Chapter 1: “What is Language?”)

Jackendoff, R. (1997) The Architecture of the Language Faculty. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

The MIT Press.

Radford, A., M. Atkinson, D. Britain, H. Clahsen & A. Spencer (2009: 2nd ed.) Linguistics: An

Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Page 4 of 4/Lesson 3’ Morphology & Syntax

You might also like

- 04B MorphologyDocument4 pages04B MorphologyGabriel Garcia BacigalupoNo ratings yet

- 4 Morphology 2015 - NEWDocument4 pages4 Morphology 2015 - NEWLaydy HanccoNo ratings yet

- Immediate Constituents: The Hierarchical Structure of WordsDocument4 pagesImmediate Constituents: The Hierarchical Structure of WordsRaghadNo ratings yet

- Vowel Phonemes: Phoneme ExamplesDocument6 pagesVowel Phonemes: Phoneme ExamplesAnna Rhea BurerosNo ratings yet

- Ling Morphology 13Document82 pagesLing Morphology 13amycheng0315No ratings yet

- MorphemesDocument18 pagesMorphemesmufidolaNo ratings yet

- Morphological Structure of A Word. Word-Formation in Modern English 1. Give The Definition of The MorphemeDocument22 pagesMorphological Structure of A Word. Word-Formation in Modern English 1. Give The Definition of The MorphemeIvan BodnariukNo ratings yet

- Seminar3 NazhestkinaDocument11 pagesSeminar3 NazhestkinaЕлена ПолещукNo ratings yet

- Morphology Is The Study of The Internal Structure of WordsDocument4 pagesMorphology Is The Study of The Internal Structure of WordsKatherine Lyons100% (1)

- Morphology Test (Lexicology), With Answers, 2021Document16 pagesMorphology Test (Lexicology), With Answers, 2021Amer Mehovic100% (2)

- Materi Kuliah Morphology & SyntaxDocument8 pagesMateri Kuliah Morphology & SyntaxcoriactrNo ratings yet

- The Underlined MorphemesDocument9 pagesThe Underlined Morphemesramesh29ukNo ratings yet

- Topic 3Document33 pagesTopic 3Danial FirdausNo ratings yet

- Morphology Exam NotesDocument18 pagesMorphology Exam NotesAlba25DG DomingoNo ratings yet

- Materi Kuliah MorphologyDocument9 pagesMateri Kuliah MorphologyMuhammad Hidayatul RifqiNo ratings yet

- Syntax and Morphology 1Document40 pagesSyntax and Morphology 1Dena Ben100% (1)

- Part of LinguisticsDocument37 pagesPart of LinguisticsNorlina CipudanNo ratings yet

- Linguistics 101: An Introduction To The Study of LanguageDocument25 pagesLinguistics 101: An Introduction To The Study of LanguagecoriactrNo ratings yet

- Linguistics 101Document14 pagesLinguistics 101Elyasar AcupanNo ratings yet

- THE GRAMMATICAL-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesTHE GRAMMATICAL-WPS OfficeLifyan AriefNo ratings yet

- Notes BIDocument6 pagesNotes BIYUSRI BIN KIPLI MoeNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document8 pagesLecture 2Катeрина КотовичNo ratings yet

- Technically, A Word Is A Unit of Language That Carries Meaning and Consists of One orDocument7 pagesTechnically, A Word Is A Unit of Language That Carries Meaning and Consists of One orDoni Setiawan sinagaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of English Language - IntroductionDocument29 pagesThe Structure of English Language - IntroductionSaripda JaramillaNo ratings yet

- Open Book Review: University of OkaraDocument15 pagesOpen Book Review: University of OkaraUsama JavaidNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 For LexicologyDocument52 pagesLecture 2 For LexicologyTinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Morphology QDocument32 pagesMorphology QShen De AsisNo ratings yet

- Words and Their Internal Structure: MorphologyDocument9 pagesWords and Their Internal Structure: MorphologyDaniela Fabiola Huacasi VargasNo ratings yet

- MORPHOLOGY SYNTAX SEMANTICS ReviewerDocument13 pagesMORPHOLOGY SYNTAX SEMANTICS ReviewerMarissa EsguerraNo ratings yet

- The Structure of English LanguageDocument26 pagesThe Structure of English Languagekush vermaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of English LanguageDocument35 pagesThe Structure of English LanguageAlexandre Alieem100% (3)

- Lexicology Is The Branch ofDocument3 pagesLexicology Is The Branch ofАқмарал СүттібайNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Course of English Grammar - Lecture 2Document5 pagesTheoretical Course of English Grammar - Lecture 2ქეთი გეგეშიძეNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Morphology Group of 3 NewwwDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Morphology Group of 3 NewwwSilvia RalikaNo ratings yet

- General Linguistics: Morphology Word StructureDocument45 pagesGeneral Linguistics: Morphology Word StructureReemNo ratings yet

- Applied Cognitive Construction Grammar: A Cognitive Guide to the Teaching of Phrasal Verbs: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #3From EverandApplied Cognitive Construction Grammar: A Cognitive Guide to the Teaching of Phrasal Verbs: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #3No ratings yet

- UNIT 2 - Lesson 2Document5 pagesUNIT 2 - Lesson 2Flor BulacioNo ratings yet

- Word Structure: Morphology: Academic Year 2021-2022Document228 pagesWord Structure: Morphology: Academic Year 2021-2022Avin HakimNo ratings yet

- Types of MorphemesDocument5 pagesTypes of MorphemesSafkat Al FayedNo ratings yet

- Morphology and SyntaxDocument7 pagesMorphology and SyntaxMuhammad Ibrahim100% (1)

- MorphologyDocument43 pagesMorphologyالاستاذ محمد زغير100% (1)

- Unit 1 The Study of Morphological Structure of EnglishDocument47 pagesUnit 1 The Study of Morphological Structure of EnglishSLRM1100% (4)

- Introduction To LinguisticsDocument5 pagesIntroduction To LinguisticsIna BaraclanNo ratings yet

- English Grammar HandbookDocument135 pagesEnglish Grammar Handbookengmohammad1No ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument27 pagesMorphologyArriane ReyesNo ratings yet

- Doctor's Notes & QuestionsDocument8 pagesDoctor's Notes & QuestionsAb ProNo ratings yet

- Morphology and SyntaxDocument3 pagesMorphology and SyntaxЮлия ПолетаеваNo ratings yet

- Lexicology-Unit 1 SlideDocument30 pagesLexicology-Unit 1 SlideBusiness English100% (1)

- FFZG Syntax 1Document26 pagesFFZG Syntax 1maja_bukalNo ratings yet

- Applied Linguistics Handout LessonDocument23 pagesApplied Linguistics Handout LessonArgene MonrealNo ratings yet

- Lexicology As A Science. The Object of Lexicology. Main Lexicological ProblemsDocument4 pagesLexicology As A Science. The Object of Lexicology. Main Lexicological ProblemsVania PodriaNo ratings yet

- Meeting 4 - MorphologyDocument38 pagesMeeting 4 - MorphologyrezaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of ADocument5 pagesLinguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of AChiara Di nardoNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument7 pagesDocumentSabrina AbdusalomovaNo ratings yet

- Applied Cognitive Construction Grammar: Understanding Paper-Based Data-Driven Learning Tasks: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #1From EverandApplied Cognitive Construction Grammar: Understanding Paper-Based Data-Driven Learning Tasks: Applications of Cognitive Construction Grammar, #1No ratings yet

- On the Evolution of Language: First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879-80, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1881, pages 1-16From EverandOn the Evolution of Language: First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879-80, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1881, pages 1-16No ratings yet

- Phonics Guidelines: Year: 2021 Class: K2 Level Term: 1 Weeks Topics Objectives Materials Needed TasksDocument3 pagesPhonics Guidelines: Year: 2021 Class: K2 Level Term: 1 Weeks Topics Objectives Materials Needed TasksElma DineNo ratings yet

- ABCE PHD Studentship Application FormDocument4 pagesABCE PHD Studentship Application Formnasibeh tabriziNo ratings yet

- UTSDocument2 pagesUTSEverlyne SiloyNo ratings yet

- Delta Module One Pre Interview Task: Name Maria Victoria Mermoz PaciDocument4 pagesDelta Module One Pre Interview Task: Name Maria Victoria Mermoz PaciMaria Victoria Mermoz PaciNo ratings yet

- Job Analysis QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesJob Analysis QuestionnairebarakatkomNo ratings yet

- 16speak Company BackgroundDocument9 pages16speak Company Background16SpeakNo ratings yet

- A Strange Case of Agoraphobia A Case StudyDocument4 pagesA Strange Case of Agoraphobia A Case StudyChhanak Agarwal100% (1)

- Spanish MaterialsDocument3 pagesSpanish MaterialsCarlos RodriguezNo ratings yet

- DLL Arts Q3 W6Document7 pagesDLL Arts Q3 W6Cherry Cervantes HernandezNo ratings yet

- Do Angels EssayDocument1 pageDo Angels EssayJade J.No ratings yet

- Meaning and Definitions of Group Dynamics - ImportanceDocument3 pagesMeaning and Definitions of Group Dynamics - ImportanceanjicieflNo ratings yet

- Reza Nazari - Farsi Reading - Improve Your Reading Skill and Discover The Art, Culture and History of Iran - For Advanced Farsi (Persian) Learners-Createspace Independent Publishing Platform (2014)Document236 pagesReza Nazari - Farsi Reading - Improve Your Reading Skill and Discover The Art, Culture and History of Iran - For Advanced Farsi (Persian) Learners-Createspace Independent Publishing Platform (2014)SlavoNo ratings yet

- Career Guide For Product Managers by ProductplanDocument139 pagesCareer Guide For Product Managers by ProductplanArka Prava Chaudhuri100% (1)

- Advantages of Oral CommunicationDocument5 pagesAdvantages of Oral CommunicationFikirini Rashid Akbar100% (2)

- Theeffectsoftechnologyonyoungchildren 2Document5 pagesTheeffectsoftechnologyonyoungchildren 2api-355618075No ratings yet

- Research DetteDocument6 pagesResearch DetteElreen AyaNo ratings yet

- Webinar On The Preparation of Melc-Based Lesson Exemplars and Learning Activity SheetsDocument25 pagesWebinar On The Preparation of Melc-Based Lesson Exemplars and Learning Activity SheetsJenne Santiago BabantoNo ratings yet

- Edtpa Pfa Context For LearningDocument3 pagesEdtpa Pfa Context For Learningapi-302458246No ratings yet

- Mental BreakdownDocument33 pagesMental BreakdownTamajong Tamajong Philip100% (1)

- Project Planning and SchedulingDocument205 pagesProject Planning and SchedulingYosef Daniel100% (1)

- PerDev ReviewerDocument4 pagesPerDev ReviewerJaira PedritaNo ratings yet

- Career Guidance Module For Grade 11 StudentsDocument43 pagesCareer Guidance Module For Grade 11 StudentsGilbert Gabrillo JoyosaNo ratings yet

- Cordova Beverlene L. - Practicum PortfolioDocument12 pagesCordova Beverlene L. - Practicum PortfolioBeverlene Enso Lesoy-CordovaNo ratings yet

- Commerce Scheme Form 4Document15 pagesCommerce Scheme Form 4methembe dubeNo ratings yet

- RW - DLP Critical Reading As ReasoningDocument8 pagesRW - DLP Critical Reading As ReasoningJulieAnnLucasBagamaspad100% (6)

- Technology Integration in The Classroom PDFDocument4 pagesTechnology Integration in The Classroom PDFDhana Raman100% (1)

- Fairclough NDocument4 pagesFairclough NAnonymous Cf1sgnntBJNo ratings yet

- Empower Second Edition Starter ESOL MapDocument10 pagesEmpower Second Edition Starter ESOL MaphgfbvdcsxNo ratings yet

- Maslow's Hierarchy of NeedsDocument7 pagesMaslow's Hierarchy of NeedsMaan MaanNo ratings yet

- CMS QAPI Five ElementsDocument1 pageCMS QAPI Five ElementssenorvicenteNo ratings yet