Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Reading 5

Uploaded by

henny-tannady-6203Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal Reading 5

Uploaded by

henny-tannady-6203Copyright:

Available Formats

Reducing wait time for cataract surgery: comparison

of 2 historical cohorts of patients in Montreal

Hélène Boisjoly,*{ MD, FRCSC, MPH; Ellen E. Freeman,*{ PhD; Fawzia Djafari,*{ MD, MSc;

Marie-Josée Aubin,*{ MD, FRCSC, MSc; Simon Couture,*{ MD, DMV, MSc; Robin P. Bruen,*{ MD;

Robert Gizicki,*{ MD; Jacques Gresset,{{ OD, PhD

ABSTRACT N RÉSUMÉ

Objective: A cataract efficiency program was implemented in Montreal in 2003 to decrease surgery wait time. Our

goal was to determine whether health, adverse events during wait time, and outcome of patients presenting for

cataract surgery differed from 1999 to 2006 in Montreal.

Design: Prospective preoperative and postoperative observational study performed at 2 time points 6 years apart.

Participants: Patients awaiting first-eye cataract surgery at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital: 509 patients in 1999–

2000 and 206 patients in 2006–2007.

Methods: Patients awaiting first-eye cataract surgery were recruited from Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital in 1999–

2000 (n 5 509) and a second cohort was recruited in 2006–2007 (n 5 206). Date of entry onto the hospital waiting list

and date of cataract surgery were recorded. About 2 weeks before surgery, patients were asked about accidents and

falls while waiting, visual difficulty, and satisfaction with vision and wait time. Visual acuity was measured in each eye.

Patients also completed interviewer-administered questionnaires: the 5-item Cataract Symptom Scale, Visual

Function–14 Questionnaire (VF-14), Short Form Health Survey–36, Geriatric Depression Scale, and the 14-item

Systemic Comorbidity Scale. The interview was repeated after surgery.

Results: In 1999, 39% of patients waited more than 6 months for cataract surgery, and this was reduced to 29% in 2006.

Patients had better preoperative visual acuity in the surgical eye, less visual difficulty, and fewer cataract symptoms,

and reported fewer accidents while waiting for surgery in 2006. The change in visual acuity after surgery was

nonetheless the same in the 2 cohorts. The 2006 cohort achieved significantly higher VF-14 scores and reported

more satisfaction with vision after surgery than did the 1999 cohort.

Conclusions: Patients had cataract surgery sooner in the disease process in 2006–2007 compared with 1999–2000,

with changes in visual acuity after surgery that were clinically significant in both cohorts.

Objet : Un programme d’efficacité concernant la chirurgie de la cataracte a été lancé en 2003 à Montréal pour en

réduire les délais d’attente. Notre but était d’établir si la santé, les délais d’attente et les résultats avaient changé

entre 1999 et 2006 chez les patients qui s’étaient présentés pour une chirurgie de la cataracte à Montréal.

Nature : Étude prospective préopératoire et postopératoire reposant sur l’observation, effectuée à deux moments, à

6 années d’intervalle.

Participants : Patients en attente d’une première chirurgie de la cataracte à l’hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont : 509

patients en 1999–2000 et 206 patients en 2006–2007.

Méthodes : Les patients attendant une première chirurgie de la cataracte à l’hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont ont été

recrutés en 1999–2000 (n 5 509) et la deuxième cohorte le fut en 2006–2007 (n 5 206). Les dates d’inscription sur la

liste d’attente de l’hôpital et celles de la chirurgie de la cataracte ont été relevées. Environ 2 semaines avant la

chirurgie, on interrogeait les patients sur les accidents et les chutes pendant le délai d’attente, ainsi que sur les

problèmes visuels et le degré de satisfaction visuelle. On a mesuré l’acuité visuelle de chaque œil. Les patients ont

aussi répondu à des questionnaires de l’intervieweur : échelle en 5 points des symptômes de la cataracte, question-

naire sur la fonction visuelle VF-14, Short Form Health Survey–36, échelle de dépression gériatrique et échelle de

comorbidité systémique en 14 points. L’entrevue a été reprise après la chirurgie.

Résultats : En 1999, 39 % des patients ont attendu la chirurgie de la cataracte plus de 6 mois. Ce taux avait baissé à 29 %

en 2006. Les patients avaient alors une meilleure acuité visuelle préopératoire dans l’œil opéré, moins de difficulté

visuelle et moins de symptômes de la cataracte; et ils ont signalé moins d’accidents en attendant la chirurgie.

Le changement d’acuité visuelle après la chirurgie était néanmoins le même dans les 2 cohortes. La cohorte de

2006 a atteint de meilleurs résultats VF-14 et s’est montrée plus satisfaite de la vision après la chirurgie que la

cohorte de 1999.

Conclusions : Les patients ont eu leur chirurgie de la cataracte plus tôt dans la progression] de la maladie en 2006–

2007, comparativement à ceux de 1999–2000, et les changements d’acuité visuelle après la chirurgie étaient

cliniquement significatifs dans les deux cohortes.

From *the Department of Ophthalmology; {the Research Center, Hôpital Correspondence to Hélène Boisjoly, MD, Research Center, Hôpital

Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montreal, Que.; and {the Department of Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Room F119, 5415 L’Assomption Blvd., Montreal,

Optometry, University of Montreal, Montreal, Que. QC H1T 2M4; helene.boisjoly@umontreal.ca

Originally received Sep. 11, 2009. Final revision Oct. 26, 2009 This article has been peer-reviewed. Cet article a été évalué par les pairs.

Accepted Nov. 14, 2009

Published online Mar. 8, 2010 Can J Ophthalmol 2010;45:135–9

doi:10.3129/i09-256

CAN J OPHTHALMOL—VOL. 45, NO. 2, 2010 135

Reducing wait time for cataract surgery—Boisjoly et al.

C ataract is the most frequent treatable blinding con-

dition worldwide.1–2 Given the aging population, it is

estimated that 1 out of 2 persons will have cataract sur-

their perceived wait time and its acceptability on a 0–4

scale, and about the occurrence of accidents and falls dur-

ing the wait. Difficulty and satisfaction with vision at the

gery.3 With the advent of technical improvements, surgery time of the interview was graded on a 0–3 scale. Patients

is now safer, with excellent outcomes, and the vision loss also completed interviewer-administered questionnaires.

threshold for surgery has decreased. In the late 1990s, wait The 5-item Cataract Symptom Scale (CSS)6–7, the Visual

time for cataract surgery was a problem in many countries, Function–14 Questionnaire ([VF-14], which measures self-

including Canada.4 We conducted a prospective study in report of difficulty with visual tasks on a 100–0 scale),6–7

1999–2000 to evaluate patient health and distress during the Short Form Health Survey-36 ([SF-36], which measures

their wait.5 Canadian provincial health ministries later general health with questions about physical, mental, and

mandated local health agencies to improve efficiency to social well-being on a 0–100 scale),8 the 30-item Geriatric

provide higher cataract surgery volumes at lower costs per Depression Scale (on a 0–30 scale), 9–10 and the 14-item

case. Performing surgery in ambulatory care centres is an Systemic Comorbidity Scale (on a 0–42 scale) were given.11

avenue of efficiency taken by many centres. After the imple- The date of entry onto the hospital waiting list and the date

mentation of a cataract efficiency program (shorter time of cataract surgery were recorded. The difference between

delays between cases, newest technology, trained surgical these 2 dates was defined as the cataract surgery wait time.

technicians, and more operating room time) in 2003 at the Patients were interviewed again between 1 and 4 months

Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital in Montreal, Que., the after surgery prior to the fellow eye surgery.

cataract surgery volume doubled. We repeated the evalu-

ation of cataract patients in 2006–2007, and compared Statistical analysis

health, adverse events during wait time, and outcome of For continuous data, medians and interquartile ranges

patients from this second cohort with that of 1999–2000. (75th–25th percentile) were given for each cohort because

many of the measures were fairly skewed. Tests between the

METHODS 2 cohorts were done using Mann-Whitney U tests for non-

parametric data. For categorical data, x2 tests were done to

Study design test for between–cohort differences. A p value of 0.05 was

The study design was a prospective preoperative and considered statistically significant. SAS software, version

postoperative hospital-based observational study per- 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) was used for the analyses.

formed at 2 time points 6 years apart.

RESULTS

Study population

Patients awaiting first-eye cataract surgery were Five hundred and nine participant patients in the first

recruited from the Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, a cohort (1999–2000) and 206 in the second cohort (2006–

large teaching hospital in Montreal, Que.: cohort 1 from 2007) completed preoperative data collection and had cat-

1999–2000 (n 5 509) and cohort 2 from 2006–2007 (n 5 aract surgery. More than 1000 nonparticipant patients

206). The later cohort was much smaller, based on sample were compared with study participants for age and gender

size calculations done for variables of interest with data in the first cohort, and no significant difference was found

obtained from the first cohort. Consecutive patients were (data not shown). Four hundred and seventy-eight patients

contacted by telephone about participation in the study (94%) in the first cohort and 182 patients (88%) in the

once their name appeared on the cataract surgery waiting second cohort also completed the postoperative evaluation.

list of the hospital. Eligibility criteria were age older than Patients who did not complete the postoperative evalu-

45 years, first-eye cataract surgery, and no obvious cogni- ation were not significantly different in age and gender

tive or auditory deficit. Signed informed consent was from those who did (data not shown).

obtained from each patient. The Ethics Committee of Patients in the 2 cohorts were fairly similar in age, gen-

the hospital approved the study. der, and general health (comorbidity level, depressive

symptoms, and SF-36 scores), although the median age

Data collection was 1 year younger (p 5 0.04) and patients had higher

Approximately 2 weeks before surgery, patients were social scores on the SF-36 questionnaire in the 2006 cohort

invited by phone to come for a research interview. Con- (p 5 0.01) (Table 1).

senting patients were enrolled. Habitual (presenting visual Vision in the surgical eye was slightly better in the more

acuity with current correction) and pinhole-corrected recent cohort (Table 2). Although the 50th percentile, or

visual acuities (pinhole was used as a surrogate for best- median, pinhole-corrected visual acuities (an estimate of

corrected visual acuity) were measured in each eye using the best-corrected visual acuity) were the same in the 2

an Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study acuity studies (0.4 logMAR, or 6/15 on the Snellen chart), the

chart and were converted to logarithm of the minimum 75th percentile acuities were better in the later cohort

angle of resolution (logMAR). Patients were asked about (0.5 logMAR, or 6/19 vs 0.6 logMAR, or 6/24, p 5 0.002).

136 CAN J OPHTHALMOL—VOL. 45, NO. 2, 2010

Reducing wait time for cataract surgery—Boisjoly et al.

The same was true of habitual visual acuity in the surgical percentile wait time in 1999–2000 was 8.5 months,

eye. Although the median habitual visual acuities were the decreasing to 6.6 months in 2006–2007 (p 5 0.01). There

same in the 2 cohorts (0.6 logMAR, or 6/24), the 75th per- were differences in how patients rated the acceptability of

centile acuities were better in the later cohort (0.9 logMAR, their cataract surgery wait time (p , 0.001) (Table 3). A

or 6/48 vs 1.0 logMAR, or 6/60, p 5 0.02). The median much greater percentage of patients in the earlier cohort

pinhole-corrected acuities in the nonsurgical fellow eye thought that their cataract surgery wait time was ‘‘not at all

were not statistically different between the 2 studies. acceptable,’’ compared with the later cohort (16% vs 4%,

However, the median habitual acuity in the nonsurgical p , 0.001). A larger percentage of patients in the first

eye was slightly better in the earlier cohort. cohort reported accidents or falls during their wait time,

Patients in the later cohort reported much less difficulty compared with the second cohort (p 5 0.001 and p 5 0.02,

on the VF-14 scale and fewer symptoms on the 5-item CSS respectively). Of the 73 accidental events, 38 were falls

(Table 2). The median VF-14 score was 66 in the 1999– (52%), 5 were auto accidents (7%), and 3 were burns (4%).

2000 cohort and 82 in the 2006–2007 cohort (lower scores The remaining 27 (37%) were not specifically described.

indicate greater difficulty) (p , 0.001). The median CSS The change in habitual and pinhole-corrected visual

score was 6 in the 1999–2000 cohort and 3 in the 2006– acuity after surgery was clinically significant in the 2

2007 cohort (p , 0.001). Patients in both cohorts cohorts (i.e., 0.3 logMAR units [3 lines on the chart] in

expressed a moderate amount of trouble with their vision the first cohort and 0.2 logMAR units [2 lines on the chart]

(median 5 moderate), although in the first cohort, patients in the second cohort [Table 4]). Postoperative habitual

were more dissatisfied with their vision (39% vs 23% were

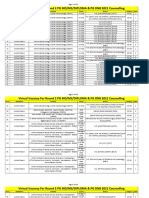

very dissatisfied) (p 5 0.001). Table 3—Adverse events during wait of participants in 1999–2000

In 1999, 39% of patients waited more than 6 months for (cohort 1) versus 2006–2007 (cohort 2)

cataract surgery, and this was reduced to 29% in 2006. The Cohort 1 (n 5 509) Cohort 2 (n 5 206) p value

mean wait time in the more recent cohort was 1.1 months Acceptance of wait time, %

shorter, falling from 6 to 4.9 months (p , 0.001). The 75th Very acceptable 20 25 ,0.001

Moderately acceptable 7 6

Acceptable 42 54

Table 1—Demographic and health characteristics of participants

in 1999–2000 (cohort 1) versus 2006–2007 (cohort 2) Somewhat acceptable 14 10

Not at all acceptable 16 4

Cohort 1 (n 5 509) Cohort 2 (n 5 206) p value

Report of accident while waiting, %

Age, y 73 (68, 79) 72 (67, 77) 0.04 Any accident* 13 4 0.001

Female gender, % 67 63 0.26 Fall 7 2 0.02

Comorbidity score 12 (7, 17) 10 (5, 17) 0.13 *Includes falls, burns, cuts, bruises, and car accidents.

SF-36 Physical 75 (50, 90) 75 (50, 90) 0.29

SF-36 Mental 76 (56, 88) 76 (64, 88) 0.06

SF-36 Social 88 (63, 100) 100 (75, 100) 0.01 Table 4—Postoperative vision after cataract surgery in 1999–2000

Geriatric Depression 6 (3, 10) 6 (3, 10) 0.79 (cohort 1) versus 2006–2007 (cohort 2)

Scale score

Data are presented as median (25%, 75%) unless otherwise indicated.

Cohort 1 Cohort 2

(n 5 478)* (n 5 182)* p value

Vision, median (25%, 75%)

Table 2—Preoperative vision of participants in 1999–2000 (cohort 1) Postop pinhole-corrected VA, 0.1 (0, 0.3) 0.1 (0, 0.2) 0.13

versus 2006–2007 (cohort 2) logMAR

Cohort 1 (n 5 509) Cohort 2 (n 5 206) p value Change in pinhole VA in surgical 0.3 (0.1, 0.4) 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) 0.08

eye, logMAR

Visual acuity,* median Postop habitual VA, logMAR 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) 0.01

(25%, 75%) logMAR

Change in habitual VA in surgical 0.3 (0.1, 0.7) 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) 0.74

Pinhole in surgical eye 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) 0.002 eye, logMAR

Habitual in surgical eye 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) 0.02 Postop VF-14 93 (83, 100) 98 (92, 100) ,0.001

Pinhole in other eye 0.2 (0.1, 0,4) 0.3 (0.2, 0,4) 0.69 Change in VF-14 23 (13, 37) 13 (2, 25) ,0.001

Habitual in other eye 0.3 (0.2, 0.5) 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) 0.02 Postop 5-item CSS 0 (0, 1) 0 (0, 1) 0.58

VF-14 66 (48, 77) 82 (68, 91) ,0.001

Change in 5-item CSS 5 (2, 7) 3 (1, 6) ,0.001

5-item CSS 6 (3, 8) 3 (1, 7) ,0.001

Problems with vision at postop, %

Problems with vision, % None 32 47 0.002

None 6 7 0.38 Few 37 32

Few 23 28 Moderate 22 16

Moderate 37 32 Many 9 4

Many 35 32 Satisfaction with vision at postop, %

Satisfaction with vision, % Very dissatisfied 8 2 ,0.001

Very dissatisfied 39 23 0.001 Moderately dissatisfied 18 8

Moderately dissatisfied 38 45 Some satisfaction 32 30

Some satisfaction 19 29 Very satisfied 42 60

Very satisfied 4 3 *Thirty-one patients (6%) in cohort 1 and 24 patients (12%) in cohort 2 were lost to follow-up

*Minimal angle resolution. after their cataract surgery.

Note: On the Snellen chart, 0.2 logMAR corresponds to 6/9.5, 0.3 to 6/12, 0.4 to 6/15, 0.5 to 6/19, Note: VA, visual acuity; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; VF-14, Visual

0.6 to 6/24, 0.7 to 6/30, 0.8 to 6/38, 0.9 to 6/48, and 1.0 to 6/60. CSS, Cataract Symptom Scale. Function–14 Questionnaire; CSS, Cataract Symptom Scale.

CAN J OPHTHALMOL—VOL. 45, NO. 2, 2010 137

Reducing wait time for cataract surgery—Boisjoly et al.

visual acuity was slightly better in the later cohort comparable to the score of 62 reported in Spain in

compared with the earlier (p 5 0.01). Conversely, there 2004–2005 in a study on 3321 patients.16

were larger improvements in VF-14 scores and in 5-item Although visual function was less impaired preopera-

CSS scores in the earlier cohort than in the later cohort tively in our 2006–2007 cohort, we still see a 16% average

because VF-14 and CSS preoperative scores were worse in improvement on the VF-14 scale, from a median score of

1999–2000 (p , 0.001). With surgery, the 2006 cohort 82 preoperatively to 98 after surgery. A ceiling effect is now

nonetheless achieved significantly higher VF-14 scores. to be expected with the VF-14 visual function scale for

The median VF-14 postoperative score in the 2006– cataract surgery (i.e., some patients have very little room

2007 cohort was 98 and in the 1999–2000 cohort was for improvement on this scale).17 This explains why the

93 (p , 0.001). Patients in 2006–2007 were more likely percentage change on the VF-14 scale is lower in the later

to report fewer problems with their vision (p 5 0.002) and cohort even though the postoperative satisfaction with

greater satisfaction with their vision (p , 0.001) post vision is significantly higher in the 2006–2007 cohort

operation than did patients in 1999–2000. and the change in habitual visual acuity is the same in

both cohorts.

CONCLUSIONS Conner-Spady et al.4 and Hodge et al.18 conducted 2

comprehensive reviews of literature pertaining to wait

Our data suggest that patients at the Maisonneuve- times for cataract surgery. They found studies reporting

Rosemont Hospital in Montreal were operated on sooner deterioration in vision after waits of more than 6 months,

in the disease process in 2006–2007, with changes in visual with an increased risk of falls, hip fractures, and motor

acuity after surgery that were clinically significant in vehicle accidents, and a reduced quality of life. We recently

both cohorts. added depression to this list of adverse outcomes of

The Montreal Health Agency invests significant patients waiting for cataract surgery.11

resources to provide higher cataract surgery volumes at We found that the self-reported accident rate while wait-

lower cost. We felt it was important to monitor the cataract ing for cataract surgery decreased in the second cohort. To

efficiency program implemented in Montreal since 2003. determine if this was due to a shorter wait time or because

We took advantage of the opportunity created by the fact patients in the second cohort had better vision, we ran a

that we had collected data prospectively in 1999–2000 and logistic regression model adjusted for age and cohort and

were in a position to compare patient population and sur- found that risk factors for a self-reported accident attri-

gical outcome of cataract patients from the same insti- buted to a vision problem during the wait time were length

tution in 2006–2007. of wait time (odds ratio [OR] 5 1.09 per 30 days, p 5

The Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital serves a popu- 0.04); visual acuity in the eye to be operated on (OR 5

lation of approximately 0.5 million people. We therefore 1.08 per 0.1 logMAR, p , 0.001); and worse 5-item CSS

estimate that the cataract surgical rate (cataracts operated per score (OR 5 1.15, p , 0.001) (data not shown).

1000 population per year) increased from 3 in 1999 (1587 The Canadian Wait Time Alliance now recommends a

cataracts surgeries/0.5 million population/year 1999) to 8 in maximum 16-week wait time for cataract surgery.19 In our

2006 (3888 cataracts surgeries/0.5 million population/year 2006–2007 cohort, more than 50% of patients still waited

2006). This last number may be somewhat overestimated more than 4 months. The Montreal Health Agency has

because the program attracted some patients from areas since added the 6-month upper limit to wait time, and the

served by other hospitals. Our numbers appear to be lower hospital must offer a private alternative if a patient has been

than those reported in Ontario by Rachmiel et al.12 How- waiting 6 months or more for cataract surgery.

ever, they are comparable to those from England, where the One limitation of our studies on wait time is that we

cataract surgical rate went from 3 in 1997 to 6 in 2005 after do not have information about the wait time to see the

the ‘‘Action on Cataract’’ initiative.13 surgeon (i.e., the time from referral by the optometrist

The Canadian Ophthalmological Society and the Amer- or the general practitioner to being seen by the ophthal-

ican Academy of Ophthalmology have eliminated a spe- mologist). More studies are required to carefully evaluate

cific visual acuity level from the criteria for performing wait times.

cataract surgery. Visual needs and functional symptoms We found that a health management program to reduce

have become accepted as the fundamental basis for decid- cataract surgery wait time and improve surgical efficiency

ing when cataract surgery is appropriate.14–15 Our study seems to have benefited cataract patients by allowing phy-

patients were therefore evaluated with the 5-item CSS, sicians to treat them sooner in the disease process, with

the VF-14 scale, and questions about problems and sat- excellent surgical results and better quality of life while

isfaction with vision, in addition to visual acuity. The later waiting and immediately after surgery. The number of

cohort perceived as many problems with their vision as the years lived with good quality of life after surgery may also

earlier cohort, although they had better visual acuity, fewer improve with such programs. The fact that the second

symptoms, and higher VF-14 scores. The VF-14 preopera- cohort was slightly younger at the time of surgery tends

tive median score of 66 in the 1999–2000 cohort is to support this assertion.

138 CAN J OPHTHALMOL—VOL. 45, NO. 2, 2010

Reducing wait time for cataract surgery—Boisjoly et al.

Future directions for this research program are to mon- Index (VF-14) and the Cataract Symptom Score. Can J Ophthal-

itor changes in patient population profile, wait times, and mol. 1997;32:31–7.

patient expectancy and outcome from cataract surgery 8. Dauphinee SL, Gauthier L, Gandek B, Magnan L, Pierre U.

in Montreal, and ideally, to compare prospective data Readying a US measure of health status, the SF-36, for use in

Canada. Clin Invest Med 1997;20:224–38.

obtained from different regions in Canada.

9. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and

This study was supported by the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Qué- validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a prelim-

bec (FRSQ; J. Gresset and H. Boisjoly), the Fonds de Recherche en inary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982–1983;17:37–49.

Ophtalmologie de l’Université de Montréal (FROUM; H. Boisjoly), 10. Bourque P, Blanchard L, Vézina J. Étude psychométrique de

and Alcon Canada (H. Boisjoly). The authors acknowledge the signifi- l’Échelle de dépression gériatrique. Can J Aging 1990;9:348–55.

cant contributions of Lucille Crépin and Annie Laporte. Surgeons

11. Freeman EE, Gresset J, Djafari F, et al. Cataract-related vision

included Marcel Amyot, MD; Marie-Josée Aubin, MD, MSc; Hélène

loss and depression in a cohort of patients awaiting cataract

Boisjoly, MD, MPH; Marie-Carole Boucher, MD; Isabelle Brunette,

MD; Jean-André DeGroot, MD; Daniel Desjardins, MD, MSc; Jean

surgery. Can J Ophthalmol 2009;44:171–6.

Dumas, MD; Éric Fortin, MD; Paul Harasymowycz, MD, MSc; Pierre 12. Rachmiel R, Trope GE, Chipman ML, Buys YM. Cataract

Labelle, MD; Michel LeFrançois, MD; Mark Lesk, MD, MSc; Michèle surgery rates in Ontario, Canada, from 1992 to 2004: more

Mabon, MD; and Francine Mathieu-Millaire, MD. The authors have surgeries with fewer ophthalmologists. Can J Ophthalmol

no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in 2007;42:539–42.

this article. 13. Sparrow JM. Cataract surgical rates: is there overprovision in

certain areas? Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:852–3.

REFERENCES 14. Canadian Ophthalmological Society evidence-based clinical

practice guidelines for cataract surgery in the adult eye. Can J

1. Brian G, Taylor HR. Cataract blindness—challenges for the Ophthalmol 2008;43(Suppl 1):S7–57.

21st century. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2001; 15. American Academy of Ophthalmology Anterior Segment Panel.

79:249–56. Preferred practice pattern. Cataract in the adult eye. San Francisco,

2. Congdon N, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, et al.; Eye Diseases Calif.: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2001.

Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of cataract and 16. Quintana JM, Escobar A, Bilbao A, et al.; IRYSS-Cataract

pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. Arch Group. Validity of newly developed appropriateness criteria

Ophthalmol 2004;122:487–94. for cataract surgery. Ophthalmol 2009;116:409–17.

3. Taylor HR. Cataract: how much surgery do we have to do? Br J 17. Bellan L. Why are patients with no visual symptoms on cataract

Ophthalmol 2000;84:1–2. waiting lists? Can J Ophthalmol 2005;40:433–8.

4. Conner-Spady B, Sanmartin C, Sanmugasunderam S, et al. A 18. Hodge W, Horsley T, Albiani D, et al.The consequences of

systemic literature review of the evidence on benchmarks for waiting for cataract surgery: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2007;

cataract surgery waiting time. Can J Ophthalmol 2007;42: 176:1285–90.

543–51. 19. Sight restoration with cataract surgery. Wait Time Alliance

5. Gresset JA, Boisjoly HM, Boivin JF, Djafari F, Cliche L. Fac- for Timely Access to Health Care Web site. Available at:

tors contributing to longer waiting times for cataract surgery. http://www.waittimealliance.ca/waittimes/sight_restoration.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000;41:S589. htm. Accessed August 6, 2009.

6. Steinberg EP, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, et al. The VF-14. An

index of functional impairment in patients with cataract. Arch

Ophthalmol 1994;112:630–8.

7. Gresset J, Boisjoly H, Nguyen TQ, Boutin J, Charest M. Keywords: cataract surgery, health care delivery, functional vision,

Validation of French-language versions of the Visual Functioning wait time

CAN J OPHTHALMOL—VOL. 45, NO. 2, 2010 139

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Health Care Delivery System in IndiaDocument14 pagesHealth Care Delivery System in IndiaSaumiya NairNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia: Update inDocument7 pagesAnaesthesia: Update inhabtishNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Medicinal Plants in North AfricaDocument2 pagesA Guide To Medicinal Plants in North Africakenpersky100% (1)

- Obstructed Labor AND ITS CAUSE, CORD PROLAPS AND PRESENTATIONDocument59 pagesObstructed Labor AND ITS CAUSE, CORD PROLAPS AND PRESENTATIONmaezu100% (2)

- Polyhydramnios CASE STUDY: Download NowDocument14 pagesPolyhydramnios CASE STUDY: Download NowJv LalparaNo ratings yet

- Medical CertificateDocument1 pageMedical Certificatekoushiksai141No ratings yet

- Partial Nail Avulsion and Matricectomy For Ingrown ToenailsDocument5 pagesPartial Nail Avulsion and Matricectomy For Ingrown ToenailsAdniana NareswariNo ratings yet

- Analysis Aiapget 2018Document4 pagesAnalysis Aiapget 2018arpit sachanNo ratings yet

- Shock ManagementDocument26 pagesShock ManagementMuhammad Irfanuddin Bin IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Toag 8 1 066 27222Document1 pageToag 8 1 066 27222Konstantinos PapadakisNo ratings yet

- Echo On Asymetrical Septal Hypertrophy PDFDocument11 pagesEcho On Asymetrical Septal Hypertrophy PDFLiesDRSJPDHKNo ratings yet

- Operational Guidelines For Establishing Sentinel Stillbirth Surveillance SystemDocument40 pagesOperational Guidelines For Establishing Sentinel Stillbirth Surveillance Systemraval anil.uNo ratings yet

- EGENS One Step HCG Cassette 2 Page InsDocument3 pagesEGENS One Step HCG Cassette 2 Page InsAdams FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Eau 2020 - Urological TraumaDocument47 pagesEau 2020 - Urological TraumaDidy KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Section 1: Internal Medicine: John Murtagh Subjectwise DivisionDocument13 pagesSection 1: Internal Medicine: John Murtagh Subjectwise DivisionJohnny Teo33% (3)

- Presentation of Alice Grainger Gasser of World Heart Federation, in World Heart Day 2016 WebinarDocument14 pagesPresentation of Alice Grainger Gasser of World Heart Federation, in World Heart Day 2016 WebinarbobbyramakantNo ratings yet

- Impact of Multimodal Intervention Strategies On Compliance To Hand Hygiene Practices Among Staff Nurses in Obstetric and Gynaecological WardsDocument1 pageImpact of Multimodal Intervention Strategies On Compliance To Hand Hygiene Practices Among Staff Nurses in Obstetric and Gynaecological WardsALYSSA MARIE MATANo ratings yet

- HO 4 Essential Intrapartum Care 6may2013Document12 pagesHO 4 Essential Intrapartum Care 6may2013Lot RositNo ratings yet

- Circumcision in Baby BoysDocument6 pagesCircumcision in Baby BoysJbl2328No ratings yet

- Jurnal GastroenterohepatologiDocument18 pagesJurnal GastroenterohepatologiRarasRachmandiarNo ratings yet

- Menorrhagia and Management PDFDocument4 pagesMenorrhagia and Management PDFrizkyNo ratings yet

- 2006FallRISE ContentOutlineDocument1 page2006FallRISE ContentOutlinewillygopeNo ratings yet

- Virtual Vacancy For Round 2 PG 2021 CounsellingDocument355 pagesVirtual Vacancy For Round 2 PG 2021 Counsellingkrish vjNo ratings yet

- Procedure Manual A4-1Document242 pagesProcedure Manual A4-1Naija Nurses TV100% (3)

- Transoperative 812217287Document27 pagesTransoperative 812217287Pepe PeñaNo ratings yet

- Legal and Ethical IssuesDocument22 pagesLegal and Ethical IssuesPratima Karki100% (1)

- Data Standarisasi Alkes Rs Ad Tk. IvDocument26 pagesData Standarisasi Alkes Rs Ad Tk. Ivrs.wirabuanaNo ratings yet

- Maternal Problems With PowerDocument2 pagesMaternal Problems With PowerAlex CvgNo ratings yet

- Caso 1 Six SigmaDocument9 pagesCaso 1 Six SigmaNayibe Tatiana Sanchez AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Espohagectomy: Done by DR - Abdallah HasandarrasDocument17 pagesEspohagectomy: Done by DR - Abdallah HasandarrasAbdallah DarrasNo ratings yet