Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Sensory Profile

Uploaded by

Mirela Lung0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1K views8 pagesThe Sensory Profile is a measure of children's responses to commonly occurring sensory experiences. Researchers conducted a discriminate analysis on the three groups. Nearly 90% of the cases were correctly classified.

Original Description:

Original Title

The sensory profile

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Sensory Profile is a measure of children's responses to commonly occurring sensory experiences. Researchers conducted a discriminate analysis on the three groups. Nearly 90% of the cases were correctly classified.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1K views8 pagesThe Sensory Profile

Uploaded by

Mirela LungThe Sensory Profile is a measure of children's responses to commonly occurring sensory experiences. Researchers conducted a discriminate analysis on the three groups. Nearly 90% of the cases were correctly classified.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Objectives.

The purpose of this study was to determine

The Sensory Profile: A which factors on the Sensory Profile, a measure of children's responses to

commonly occurring sensory experiences, best discriminate among children

Discriminant Analysis of with autism or pervasive developmental disorder (PDD), children with attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and children without disabilities.

Children With and Without Method. Data for three groups of children 3 to 15 years of age were used: 38

children with autism or PDD, 61 with ADHD, and 1,075 without disabilities. The

Disabilities researchers conducted a discriminate analysis on the three groups, using

group membership as the dependent variable and the nine factors of the

Sensory Profile as independent variables.

Julie Ermer, Winnie Dunn

Results. The analysis yielded two discriminant functions: one that

differentiated children with disabilities from children without disabilities and

Key Words: attention deficit disorder with

another that differentiated the two groups of children with disabilities from each

hyperactivity • autism • evaluation process,

other. Nearly 90% of the cases were correctly classified with these two

occupational therapy functions.

Conclusion. The Sensory Profile is useful for discriminating certain groups of

children with disabilities. Children with disabilities are accurately classified into

disability categories with the factors described by previous authors. This

suggests that patterns of behavior associated with certain developmental

disorders are reflected in populations of children without disabilities. It may be

the frequency or intensity of certain behaviors that differentiate the groups.

Occupational therapists offer a unique perspective in the

delivery of service to children with disabilities by considering

the sensory aspects of behavior. From a sensory integrative

perspective, an underlying facet of many of the behaviors

observed in children with disabilities is to either generate or

avoid sensory stimulation. Determining a child's threshold for

tolerating sensory stimuli helps families and other professionals

to understand a child's reaction to experiences easily tolerated

by peers. Determining sensory preferences may also guide

therapists in their choice of activities. A contextually relevant

Julie Ermer, MS, OTR, is Coordinator of Training in Occupational evaluation of the impact of sensory experiences on children's

Therapy, Child Development Unit, University of Kansas Medical ability to function within their environment (i.e., home, school,

Center, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Kansas City, Kansas 66160-7340. community) is an important part of an occupational therapy

assessment. Recent studies have incorporated the use of the

Winnie Dunn, PhD, FAOTA, is Professor and Chair, Department of Sensory Profile (Dunn & Westman, 1995) in the diagnostic

Occupational Therapy Education, University of Kansas Medical Center, evaluation of sensory behaviors in children with and without

Kansas City, Kansas. disabilities (Bennett & Dunn, in press; Dunn, 1994;

Dunn & Brown, 1997; Kientz & Dunn, 1997) as a

This article was accepted for publication April 21, 1997.

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 283

potential method for including sensory data in the diagnostic "shows strong preference for certain tastes" and a 38%

process. difference on the item "picky eater, especially regarding

The Sensory Profile was developed by Dunn and colleagues textures" from the Sensory Profile. It is hypothesized that Factor

to assess the responses of both children with disabilities and 4 may discriminate children with autism or PDD from children

children without disabilities to a variety of commonly occurring with ADHD and children without disabilities.

sensory experiences. Parents report the frequency their child Factor 5 contains seven items describing inattention and

responds to 125 commonly occurring experiences. Items distractibility. Although these behaviors are seen in a variety of

compiled from the literature fall into eight categories: Auditory, disability categories, the disability best represented by these

Visual, Activity Level, Taste/Smell, Body Position, Movement, characteristics is ADHD. According to the most recent

Touch, and Emotional/Social. diagnostic criteria for ADHD, inattention, hyperactivity, and

From a national sample of children without disabilities, impulsivity are hallmark symptoms of the disorder (APA, 1994).

Dunn and Brown (1997) analyzed Sensory Profile scores through Distraction by extraneous stimuli is included in the diagnostic

an exploratory factor analysis. Their findings were consistent criteria for ADHD. Many researchers have studied the ability of

with the hypothesis that the resulting factors would reflect children with ADHD to process and respond to sensory

homogeneity of responses (either high or low threshold information (Barkley, Grodzinsky, & DuPaul, 1992; Carter,

responses) to a variety of stimuli across sensory categories. The Krener, Chaderjian, Northcutt, &Wolfe, 1995; Leung &

nine resulting factors in children without disabilities are listed in Connolly, 1994; Schachar, Tannock, Marriott, & Logan, 1995).

the Appendix. Ayres (1979) theorized that children with ADHD have decreased

Of particular interest in the present study were the factors sensory processing abilities because they are easily

containing items that appeared consistent with the diagnostic overstimulated and react to stimuli that children without

criteria for groups of children with disabilities. Certain patterns disabilities commonly ignore or "tune out" (e.g., the dog

of behavior, as represented by the items in the factor groupings in barking, a light flashing). Because these children constantly react

Dunn and Brown's (1997) large sample of children without to extraneous stimuli, they appear distracted and overactive.

disabilities, closely resembled patterns of behavior accepted as When Bennett and Dunn (in press) used the Sensory Profile to

symptomatic for certain groups of children with disabilities. For compare the sensory behaviors of children with ADHD to those

example, Factor 4 (Oral Sensory Sensitivity) described the of children without disabilities, they found significant differ-

clinical signs associated with autism and pervasive ences between the two groups on 113 of the 125 items. They

developmental disorder (PDD), whereas Factor 5 found a clinically significant difference on 42 items (i.e., a raw

(Inattenrion/Distracribil-ity) appeared to contain items consistent score difference of one point or more on the five-point Likert

with the diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity scale), 30 of which fell exclusively within Factors 1 (Sensory

disorder (ADHD). Seeking), 2 (Emotionally Reactive), and 5

Factor 4 contains nine items that describe sensitivity to (Inattention/Distractibility).

particular tastes, textures, and temperatures of food. Foods that In sum, the Sensory Profile appears to contain items that

are typically pan of a child's diet might be aversive to children capture the heterogeneity of the population of children without

who have a strong preference for or a strong aversion to smells or disabilities. Through a factor analysis, patterns of behavior (i.e.,

who routinely smell nonfood items. Professionals have observed the factor groupings) emerged that seemed to indicate high or

these behaviors in children with autism or PDD (Ayres & Tickle, low thresholds for various types of sensory experiences (Dunn &

1980; Kientz & Dunn, 1997). Although the quality or frequency Brown, 1997). Because certain factors contain items that appear

of sensory responses is not included in the diagnostic criteria for consistent with the diagnostic criteria for disability categories

autism or PDD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994), such as ADHD or autism and PDD, perhaps these factors or

abnormal responses to sensory experiences in children with combinations of factors will discriminate children without

autism or PDD have been studied and are accepted as clinically disabilities from children with disabilities. The purpose of this

significant (Baranek & Berkson, 1994; Bauer, 1995; DiLalla & study was to determine the Sensory Profile factors that best

Rogers, 1994; Ornitz, 1989). Ayres and Tickle (1980) found that discriminate children with autism or PDD, children with ADHD,

the 10 children with autism that they studied, as a whole, were and children without disabilities.

hyporeactive to particular smells and tastes but were hyper-

reactive to touch (i.e., textures). Kientz and Dunn (1997) found a Method

25% difference between children with autism or PDD and Sample

children without disabilities on the item Parents of children with autism or PDD, children with

284 April 1998, Volume 52, Number 4

ADHD, or children without disabilities provided the data for this researchers as part of a large database, see references cited for

study. The data were accessed from a large database compiled details of procedures (Bennett & Dunn, in press;

from previous studies and added to by the first author. Dunn & Westman, 1997; Kientz & Dunn, 1997).

Children with autism or PDD. This group consisted of a

convenience sample of 38 children 3 to 13 years of age. This Data Analysis

group came from two sources: (a) children diagnosed by To identify the factors on the Sensory Profile that best dis-

independent physicians or by state diagnostic centers who were criminate among children with autism or PDD, children with

receiving services through the Northwest Missouri Autism ADHD, and children without disabilities, a three-group, direct-

Consortium (Kientz & Dunn, 1997) and (b) children evaluated entry discriminant analysis was conducted. Discriminant

and diagnosed by a transdisciplinary team at the Child analysis is a statistical procedure useful for classifying cases into

Development Unit at the University of Kansas Medical Center. one or more groups on the basis of various characteristics. It

Children with ADHD. This group consisted of a offers information as to which characteristics discriminate best

convenience sample of 61 children 3 to 15 years of age collected between groups and analyzes the precision of these

by Bennett and Dunn (in press). These children were diagnosed characteristics for group classification (Pormey &Watkins, 1993;

at the University of Kansas Children's Center, ADHD Clinic. The Stevens, 1992).

Sensory Profile was administered after the diagnosis was In this study, the dependent variable was diagnostic group.

established and after intervention had been initiated. The nine factors obtained in Dunn and Browns (1997) factor

Children without disabilities. This sample was taken from analysis were treated as subscales, and the scores calculated for

data collected for a national study (Dunn & West-man, 1997). each factor were the independent variables (see Appendix). We

The group consisted of 1,075 children 3 to 10 years of age who calculated factor scores for each child by multiplying the item's

were not receiving any special education services or taking factor loading by the child's score on that item and then

medications regularly (e.g., for hyperactivity, seizures). summing these products to produce a single score. Because this

analysis excluded children who had missing data, we inserted

Instrument group means for each item that contained missing data in the

The Sensory Profile (Dunn & Westman, 1995) is a 125-item groups of children with disabilities in order to increase the

assessment on which parents report the frequency their child number of cases available for the analysis. A total of 432 (8.3%)

responds to items in eight categories: Auditory, Visual, group item means were inserted, 123 (1.6%) items for the

Taste/Smell, Movement, Body Position, Touch, Activity Level, children with ADHD and 319 (6.7%) items for the children with

and Emotional/Social. This frequency is determined from a autism or PDD. Missing data points were scattered throughout

Likert scale where 1 = always: when presented with the the samples. Group means were not inserted in the group of

opportunity, the child responds in the manner described every children without disabilities, resulting in 671 children from this

time, or 100% of the time; 2 = frequently, or at least 75% of the group available for the analysis. The data were analyzed with the

time; 3 = occasionally, or 50% of the time; 4 = seldom, or 25% Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS-X) version 6.0

of the time; and 5 = never: when presented with the opportunity, (Green, Salkind, &Akey, 1997).

the child never responds in this fashion, or 0% of the time.

Results

Procedure

Parents provided informed consent before filling out the Sensory Seven hundred sixty-nine cases were analyzed in the dis-

Profile. Sensory Profile forms completed during scheduled clinic criminant analysis. Although the sample sizes varied dra-

visits required signed consent forms. Sensory Profile forms matically, each approximated a normal distribution and,

obtained through mailings contained a consent form and stated therefore, did not violate the assumptions of normal distribution.

that returning the forms to the researcher indicated consent to However, the assumption of homogeneity of variance was

participate. The researcher was available by phone to answer violated. Because the variance was smallest in the largest group

parents' questions, and, in some instances, the researcher was (children without disabilities) the results of this analysis must be

present while the forms were being completed. Because the interpreted conservatively.

majority of data used in this study was gathered by other The discriminant analysis yielded two discriminant

functions. A discriminant function is a combination of variables

(i.e., factors) that best discriminates groups. The first

discriminant function accounts for the most variability between

groups. The second accounts for the next highest amount of

variability. In this study, a factor was considered to be a good

discriminator if its discriminant

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 285

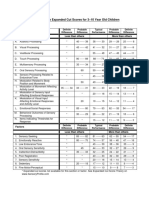

function coefficient was greater than ± .50 (see Table 1). The Table 1 Standardized Canonical Discriminant Function

first discriminant function discriminated children with disabilities Coefficients

from children without disabilities. The only factor that was a

significant discriminator was Factor 5 Factor Name Function 1 Function 2

(Inattention/Distractibility). The second discriminant function Factor 1; Sensory Seeking .19478 -.62525

Factor 2: Emotional Reactive .26899 -.18804

discriminated children with autism or PDD from children with Factor 3: Low Endurance/Tone .07318 .27184 .

ADHD. Factors 1 (Sensory Seeking), Factor 4: Oral Sensory Sensitivity -.16139 .72225

4 (Oral Sensory Sensitivity), and 9 (Fine Motor/Perceptual) were Factor 5: Inattention/Distractibility .62025 -.28053

Factor 6: Poor Registration .16911 .19576

the significant discriminators. The discriminant analysis bases its Factor 7: Sensory Sensitivity -.02468 .05771

classification on the combination of the first and second Factor 8: Sedentary -.09243 -.08965

discriminant functions. The combination of high and low Factor 9: Fine Motor/Perceptual .13869 .67066

incidence of behavior on the factors that performed as the best

discriminators are listed in Table 2. On the basis of these two tions of high or low scores on these factors created a pattern or

profile for children without disabilities, children with ADHD,

functions, 89.08% of the cases were correctly classified into one

and children with autism or PDD.

of the three groups. The children without disabilities were

slightly more likely to be correctly classified with these two func- Profile of children without disabilities. Sensory processing

is a well-established component of many theories of learning and

tions than either of the two groups of children with disabilities

(see Table 3). development (Ayres, 1979; Piaget, 1952;

Reilly, 1974). Children seek information about their world

The scatterplot presented in Figure 1 illustrates the

through the senses and use this information to form adaptive

relationship of the three groups to each other, using the two

discriminant functions as variables. The group cen-troid of responses. The findings of this study support these theories in

that children without disabilities were discriminated best by a

children without disabilities is very close to neutral, with very

high level of behaviors in Factor 1. In addition to a high

small positive values of discriminant functions 1 (horizontal axis)

and 2 (vertical axis). Table 2 shows that children without incidence of behaviors in Factor 1, the profile of a child without

disabilities also includes a low incidence of behaviors in Factors

disabilities have a relatively high incidence of behaviors in

Factor 1 and a relatively low incidence of behaviors in Factors 4, 4, 5, and 9. So, despite their level of activity, children without

disabilities, as a group, do not show patterns of inattention,

5, and 9. A low score indicates a high level of behaviors as 1 =

distractibility, or oral sensory sensitivity when compared with

always and

their peers who have disabilities. Their scores on the Sensory

5 = never.

Children with autism or PDD have a group centroid located Profile suggest that they do not, as a group, experience the same

in the negative region on discriminant functions 1 and 2 (see difficulties with fine motor and academic (perceptual) tasks.

Figure 1). The combinations of functions in Table 2, illustrates a Their overall pattern of scores suggest that they adapt

high incidence of behaviors in Factors 4, 5, and 9 and a low appropriately to sensory input.

incidence of behaviors in Factor 1 for this group. In contrast, the Profile of children with ADHD. Children with ADHD are

group centroid for the children with ADHD has a negative value known to exhibit many of the sensory seeking behaviors seen in

for discriminant function 1 and a positive value for discriminant children without disabilities, but with greater frequency or

function 2. This indicates a high incidence of behaviors in intensity (Bennett & Dunn, in press). In addition to sensory

Factors 1 and 5 and low incidence of behaviors in Factors 4 and 9 seeking behaviors, inattention and distractibility tend to impair a

(see Table 2). child's ability to function across environments (APA, 1994).

This study supports these findings in that children with ADHD

Discussion were best discriminated by a high incidence of behaviors in

Discrimination of Groups Factors 1 and 5 and a low incidence of behaviors in Factors 4

The hypothesis put forth by Dunn and Brown (1997) that the and 9.

Sensory Profile factors found in children without disabilities

would discriminate children with and children without Table 2 Classification Based on Discriminant

disabilities was true in our study, as nearly 90% of the 769 cases Functions 1 and 2

were correctly classified using the nine Sensory Profile factors as Factor 5: Factor 9:

Factor 1: Factor 4: Inattention/ Fine Motor/

discriminators. Of these nine factors, Factors 1 (Sensory

Group_____SensorySeeking OralSensitivity Disnacdbility Perceptual

Seeking), 4 (Oral Sensory Sensitivity), 5 No disabilities + 0 0 0

(Inattention/Distractibility), and 9 (Fine Motor/Perceptual) were ADHD + 0 + 0

the best discriminators. Combina- Autism or PDD 0 + + +

Note. + = low score on this factor (high incidence of behaviors wirhin this factor); 0 = high score

on this factor (low incidence of behaviors within this factor). ADHD = attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder; PDD s= pervasive developmental disorder.

286 April 1998, Volume 52, Number 4

Table 3 ences create functional impairments across environments.

In this study, children with autism or PDD differed most from

Group Number No Disabilities n ADHD n (%) Autism or PDD the other two groups by a relatively low incidence of behaviors

of Cases (%) n (%)

in Factor 1 and a high incidence of behaviors in Factors 4, 5,

No disabilities 671 60 38 609 (90.8%) 5 23 (3.4) 46 39 (5.8) 9 and 9. In essence, the profile of children with autism was

ADHD Autism or (8.3) 4 (10.5) (76.7) (15.0) 30 opposite that of a child without disabilities.

PDD 4(10.5) (78.9)

Note. Percent of "grouped" cases correctly classified = 89.08%. ADHD =

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; PDD = pervasive developmental Practice Implications

disorder. Evaluation. Information regarding the way a child responds to

sensory events within home and community environments is

In this analysis, children with ADHD differed from children important information that should be made available to the

without disabilities in inattention and distracti-bility. In their diagnostic team. Children with behavioral disorders such as

analysis of children with ADHD and children without autism or PDD and ADHD process sensory information

disabilities, Bennett and Dunn (in press) found that differences differently than children without disabilities (Ayres, 1979;

between these groups were on items within Factors 1, 2 Bennett & Dunn, in press; Kientz & Dunn, 1997). Because the

(Emotionally Reactive), and 5. The means for children with Sensory Profile is sensitive to these differences and can

ADHD differed from children without disabilities on certain discriminate between these two disability groups, this measure

items by more than one point. This may suggest that although the may be useful in the evaluation process to screen for autism,

pattern of sensory seeking behaviors (Factor 1) in children with PDD, or ADHD. Additionally, because the Sensory Profile relies

ADHD may resemble that of children without disabilities, the on parental report of observed behaviors and the frequency or

incidence or frequency of the behaviors is markedly higher. intensity of behaviors within the child's natural environment, its

Profile of children with autism or PDD. Researchers in the use encourages parental involvement in the evaluation process.

field of occupational therapy have addressed the atypical and Parents are often uniquely intuitive regarding their child's

often bizarre responses of children with autism or PDD to behavior and are able to highlight behaviors not readily

sensory experiences (Ayres & Tickle, 1980). Repetitive observable in traditional testing arenas.

stereotyped behaviors, self-stimulation, or strong aversive Intervention. Because the Sensory Profile allows par-

responses to commonly occurring sensory experi

Children:

WithoutDisabilities

• With Autism/PDD

With ADHD

Function 1

Figure 1. Discriminant analysis results.

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 287

ents to highlight the behaviors interfering with their child's a continuum of sensory responses and behaviors that dis-

functioning, the measure can be useful to therapists in planning criminates groups of children from each other, suggesting that

contextually relevant interventions. The assessment's data can frequency, intensity, or the patterns in which the behaviors

inform therapists about which sensory systems might be affected appear may be an important feature of diagnosis.

and which patterns of behavior (i.e., factors) might be more The Sensory Profile was originally created as a tool to

indicative of the child's performance. Designing an environment assess the responses of children to naturally occurring sensory

that includes the child's preferred stimuli and that controls the experiences in their everyday environments (i.e., home, school,

stimuli the child perceives as aversive is a key intervention community). Because existing tools had not considered naturally

strategy. occurring experiences in context or were not validated for use

with groups of children with disabilities, the results of this study

Limitations and Directions for Future Research support the Sensory Profile as a useful tool for certain groups of

Several limitations were inherent in this study. The use of children with disabilities. A

convenience samples for the two groups of children with

disabilities warrants further studies for regional differences. The Acknowledgments

We thank Catana Brown, MA, OTR, for assistance with the statistical

vast discrepancy in sample sizes (i.e., relatively small samples of analysis. This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the first

children with disabilities) was noted. Larger samples of children author's requirements for a master of science degree in occupational

with disabilities would further validate the findings. Because the therapy.

assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated, results of

Appendix Factor Analysis Item List (Dunn & Brown, 1997)

the discriminant analysis should be conservatively interpreted.

Finally, because only two disability groups were chosen for this Factor 1: Sensory Seeking

study, no predictions can be made about how other disability

groups might be discriminated and classified. Further research

Movement 10 Takes excessive risks during play

using other samples of children with disabilities would provide

additional information regarding the validity for the use of the Movement 11 Takes movement or climbing risks during

Sensory Profile in other groups of children with disabilities. play that compromise personal safety.

Movement 9 Continually seeks out all kinds of movement

Conclusion activities.

Occupational therapists bring to the interdisciplinary team

expertise in sensory processing and its impact on performance in Body Position 1 Seeks opportunities to fall without regard

daily life. Although sensory processing problems have not to personal safety.

explicitly been included in diagnostic criteria for children, this Movement 5 Seeks all kinds of movement, and this

study provided evidence that some performance difficulties may interferes with daily routines.

be associated with poor sensory processing and may be specific Movement 14 Twirls/spins self frequently throughout

to particular disabilities. As our knowledge of how disabilities

the day

affect children's performance increases, so does our ability to

Body Position 7 Appears to enjoy falling

offer useful information to families regarding status, prognosis,

and options for intervention. Populations of children with dis- Movement 17 Becomes overly excitable after a movement

abilities exhibit patterns of behavior that are distinguishable activity

from children without disabilities. Identifying how these patterns Movement 18 Turns whole body to look at you

resemble or differ from those of children who are developing Touch 21 Always touching people and objects

typically leads to more accurate assessment and intervention Auditory 3 Enjoys strange noises/seeks to make noise

planning options.

for noise sake.

The results of this study indicate that the Sensory Profile

Emotional/Social 5 Is overly affectionate with others

contains items and factors that not only have the ability to

discriminate children with disabilities from children without Activity Level 1 Jumps from one activity to another so

disabilities, but also to discriminate groups of children with frequently it interferes with play

disabilities from each other. The factor structure profiled in Body Position 2 Hangs on other people, furniture, objects

children without disabilities indicates even in familiar situations

Touch 23 Doesn’t seem to notice when face or hands

are messy

Factor 2: Emotionally Reactive

Emotional/Social 11 Has difficulty tolerating change in plans

and expectations

Emotional/Social 10 Displays emotional outbursts when

unsuccessful at a task

Emotional/Social 20 Poor frustration tolerance

Emotional/Social 21 Cries easily

Emotional/Social 15 Has difficulty tolerating changes in routines Factor 6: Poor Registration

Emotional/Social 8 Seems anxious

Emotional/Social 6 Is sensitive to criticisms Emotional/Social 18 Doesn’t express emotions

Emotional/Social 2 Seems to have difficulty liking self Emotional/Social 19 Doesn’t perceive body language or facial

Emotional/Social 12 Expresses feeling like a failure expressions

Emotional/Social 13 Is stubborn or uncooperative Emotional/Social 22 Doesn’t have a sense of humor

Emotional/Social 7 Has definite fears Touch 22 Doesn’t seem to notice when someone

Emotional/Social 4 Has trouble “growing up” touches arm or back

Emotional/Social 14 Has temper tantrums Visual 18 Doesn’t notice when people come into

Emotional/Social 3 Needs more protection from life than other the room

children Taste/Smell 10 Does not seem to smell strong odors

Emotional/Social 24 Has difficulty making friends Touch 20 Decreased awareness of pain and

Emotional/Social 23 Overly serious temperature

Touch 9 Avoids going barefoot, especially in sand

Factor 3: Low Endurance/Tone or grass

Body Position 3 Seems to have weak muscles Factor 7: Sensory Sensitivity

Body Position 4 Tires easily, especially when standing or

holding a particular body position Movement 1 Becomes anxious or distressed when feet

Body Position 9 Has a weak grasp leave ground

Body Position 5 Locks joints for stability Movement 2 Fears falling or heights

Body Position 10 Can’t life heavy objects Movement 3 Dislikes activities where head is upside

Movement 20 Poor endurance/tires easily down or roughhousing

Body Position 11 Props to support self Movement 4 Avoids climbing, jumping, bumpy or

Body Position 8 Moves stiffly uneven ground

Movement 21 Appears lethargic

Factor 8: Sedentary

Factor 4: Oral Sensory Sensitivity

Movement 19 Prefers sedentary activities

Taste/Smell 6 Shows preference for certain tastes Movement 6 Seeks sedentary play options

Taste/Smell 5 Will only eat certain tastes Activity Level 3 Spends most of the day in sedentary play

Taste/Smell 4 Shows a strong preference for certain smells Activity Level 4 Prefers quiet, sedentary play

Taste/Smell 2 Avoids certain tastes/smells that are

typically part of children’s diets Factor 9: Fine Motor/Perceptual

Touch 12 Picky eater, especially regarding textures

Taste/Smell 8 Craves certain foods Visual 14 Has trouble staying between the lines when

Taste/Smell 9 Seeks out certain taste/smells coloring or when writing

Touch 6 Limits self to particular food

Taste/Smell 3 Routinely smells nonfood objects Visual 7 Writing is illegible

Visual 8 Has difficulty putting puzzles together

Factor 5: Inattention/Distractibility Emotional/Social 14 Has temper tantrums

Auditory 2 Is distracted or has trouble functioning if

there is a lot of noise around References

Activity Level 6 Difficulty paying attention American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statis-

tical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). Washington, DC: Author.

Auditory 4 Appears not to hear what you say

Ayres, A. (1979). Sensory integration and the child. Los Angeles:

Auditory 6 Can’t work with background noise Western Psychological Services.

Auditory 7 Has trouble completing tasks when the Ayres, A. ]., & Tickle, L. S. (1980). Hyper-responsivity to touch

and vesribular stimuli as a predictor of positive response to sensory

radio is on integration procedures by autistic children. American Journal of

Auditory 8 Doesn’t respond when name is called Occupational Therapy, 34, 375-381.

Baranek, G., & Berkson, G. (1994). Tactile defensiveness in

Visual 1 Looks away from task to notice all actions

children with developmental disabilities: Responsiveness and habitua-

in the room tion. Journalof'Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 457—471.

Barkley, R., Grodzinsky, G., & DuPaul, G. (1992). Frontal lobe

functions in attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity: Green, S. B., Salkind, N. J., & Akey, T. M. (1997). Using SPSS for

A review and research report. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, windows: Analyzing and understanding data. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

20(2), 163-188. Prentice Hall.

Bauer, S. (1995). Autism and pervasive developmental disorders: Kientz, M. A, & Dunn, W. (1997). A comparison of the perfor-

Part 1. Pediatrics in Review, 16, 130-136. mance of children with and without autism on the Sensory Profile.

Bennett, D., & Dunn, W. (in press). Comparison of sensory American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 530-537.

characteristics of children with and without attention deficit hyperac- Leung, P., & Connolly, K. (1994). Attenrional difficulties in

tivity disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. hyperactive and conduct disordered children: A processing deficit.

Carter, C., Krener, P., Chaderjian, M., Northcutt, C., &Wolfe, V. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 1229-1245.

(1995). Abnormal processing of irrelevant information in attention Ornitz, E. (1989). Autism at the interface between sensory processing

deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Research, 56(1), 59-70. and information processing. In G. Dawson (Ed.), Autism: Nature,

DiLalla, D., & Rogers, S. (1994). Domains of the Childhood diagnosis, andtreatment(pp. 174-207). New York: Guilford.

Autism Rating Scale: Relevance for diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. New York:

Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 115-128. Norton.

Dunn, W. (1994). Performance of typical children on the Sensory Portney, L, & Watldns, M. (1993). Foundations of clinical re-

Profile: An item analysis. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, search: Applications to practice. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange.

48, 967-974. Reilly, M. (1974). Play as exploratory behavior. Beverly Hills,

Dunn, W., & Brown, C. (1997). Factor analysis on the Sensory CA:Sage.

Schachar, R., Tannock, R., Marriott, M., & Logan, G. (1995).

Profile from a national sample of children without disabilities. American

Deficient inhibitory control in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 490^95.

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23,411—437.

Dunn, W., 8; Westman, K. (1995). The Sensory Profile. Un-

Stevens, J. (1992). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sci-

published manuscript, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas

ences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Eribaum

City.

Dunn, W., & Westman, K. (1997). The Sensory Profile: The per-

formance of a national sample of children without disabilities. American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 25—34.

You might also like

- Executive Function and Self-Regulation in ChildrenFrom EverandExecutive Function and Self-Regulation in ChildrenRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Short Sensory ProfileDocument11 pagesShort Sensory ProfileNurul Izzah Wahidul Azam100% (1)

- Sensory Diet: Prepared by Christy E. Yee, OTRDocument12 pagesSensory Diet: Prepared by Christy E. Yee, OTRAlexandra StăncescuNo ratings yet

- Sensory Profile: Submitted By-Amandeep Kaur M.O.T-Neuro, Sem 3 ENROLLMENT NO - A138141620004 Guided by - Ruby Ma'AmDocument42 pagesSensory Profile: Submitted By-Amandeep Kaur M.O.T-Neuro, Sem 3 ENROLLMENT NO - A138141620004 Guided by - Ruby Ma'Amamandeep kaurNo ratings yet

- Sensory Diet Handout for Developmental FXDocument7 pagesSensory Diet Handout for Developmental FXpratibhaumrariya100% (1)

- Sensory Profile Expanded Cut Scores For 3-10 Year Old ChildrenDocument1 pageSensory Profile Expanded Cut Scores For 3-10 Year Old ChildrenAyra MagpiliNo ratings yet

- Supporting Children To Participate Successfully in Everyday Life Using Sensory Processing KnowledgeDocument19 pagesSupporting Children To Participate Successfully in Everyday Life Using Sensory Processing Knowledgeapi-26018051100% (1)

- Day 1: The Ultimate Guide To Decoding A Child's Sensory SystemDocument45 pagesDay 1: The Ultimate Guide To Decoding A Child's Sensory SystemLuca ServentiNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Executive Functioning in ChildrenDocument37 pagesThe Assessment of Executive Functioning in Childrenluistxo2680No ratings yet

- Helping Hands-Website InformationDocument17 pagesHelping Hands-Website InformationDiana Moore Díaz100% (1)

- Using Sensory Integration andDocument9 pagesUsing Sensory Integration andVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy Ia Sample ReportsDocument11 pagesOccupational Therapy Ia Sample Reportssneha duttaNo ratings yet

- 11 17 17 Treatment PlanDocument7 pages11 17 17 Treatment Planapi-435469413No ratings yet

- 132 Sensory Diet 090212Document2 pages132 Sensory Diet 090212Sally Vesper100% (1)

- Marcus Evaluation - StruthersDocument8 pagesMarcus Evaluation - Struthersapi-355500890No ratings yet

- A Review of Pediatric Assessment Tools For Sensory Integration AOTADocument3 pagesA Review of Pediatric Assessment Tools For Sensory Integration AOTAhelenzhang888No ratings yet

- Winnie Dunn Sensory Profile PDFDocument17 pagesWinnie Dunn Sensory Profile PDFYonaa K100% (1)

- Ota Watertown Si Clinical Assessment WorksheetDocument4 pagesOta Watertown Si Clinical Assessment WorksheetPaulinaNo ratings yet

- Supporting Therapy in The Classroom Strategies For OccupationalDocument70 pagesSupporting Therapy in The Classroom Strategies For Occupationalapi-451269263No ratings yet

- Ot GuidelinesDocument107 pagesOt GuidelinesAhmed MaherNo ratings yet

- Sensory Curriculum For Individuals On The Autism SpectrumDocument5 pagesSensory Curriculum For Individuals On The Autism SpectrumSuperfixen100% (1)

- 7 (SPM™) Sensory Processing Measure™ - WPSDocument1 page7 (SPM™) Sensory Processing Measure™ - WPSVINEET GAIROLA14% (7)

- Sensory Regulation ConferenceDocument19 pagesSensory Regulation ConferenceSebastian Pinto ReyesNo ratings yet

- Sensory Integration PDFDocument1 pageSensory Integration PDFmofasorgNo ratings yet

- Making Sense Sensory Processing Disorder103114Document61 pagesMaking Sense Sensory Processing Disorder103114Branislava Jaranovic Vujic100% (5)

- Sensory Integration in The Home: An OverviewDocument28 pagesSensory Integration in The Home: An OverviewEileen Grant100% (6)

- Motor Skills AutismDocument16 pagesMotor Skills AutismmarkonahNo ratings yet

- Sensory AssesmentDocument19 pagesSensory AssesmentBurçin KaynakNo ratings yet

- Beery Vmi Performance in Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument33 pagesBeery Vmi Performance in Autism Spectrum DisorderJayminertri Minorous100% (1)

- Sensory Processing 101: Understanding Sensory Challenges in ASDDocument75 pagesSensory Processing 101: Understanding Sensory Challenges in ASDjahirmiltonNo ratings yet

- Sensory Profile PowerpointDocument21 pagesSensory Profile PowerpointLama NammouraNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy - Play, SIs and BMTsDocument3 pagesOccupational Therapy - Play, SIs and BMTsAnnbe Barte100% (1)

- InTech-Sensory Motor Development in AutismDocument26 pagesInTech-Sensory Motor Development in AutismTânia DiasNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument12 pagesCase Study宗轶烜100% (1)

- Facilitation Techniques in Prone PositionDocument37 pagesFacilitation Techniques in Prone PositionMartha FrankNo ratings yet

- Sensory Assessment ChecklistDocument3 pagesSensory Assessment ChecklistElaime MaciquesNo ratings yet

- Screening SensorimotorDocument29 pagesScreening Sensorimotoramitesh_mpthNo ratings yet

- Sensory Processing Disorder Checklist: Signs of DysfunctionDocument7 pagesSensory Processing Disorder Checklist: Signs of DysfunctionLalitha Raja100% (1)

- Early Autism Red Flags Infants Toddlers PreschoolersDocument3 pagesEarly Autism Red Flags Infants Toddlers PreschoolersHemant KumarNo ratings yet

- OT For Children With ADHDDocument12 pagesOT For Children With ADHDBeatrizIgelmo100% (1)

- Sensory Diet 2Document2 pagesSensory Diet 2Pamm50% (2)

- sp2 Child Full Assessment Sample PDFDocument15 pagessp2 Child Full Assessment Sample PDFLalit Mittal100% (2)

- Sensory ProfileDocument8 pagesSensory ProfilenymommyNo ratings yet

- PD Sensory Room TrainingDocument35 pagesPD Sensory Room Trainingapi-393264699No ratings yet

- AutismMotorSkillEvaluationFINALBESt028.8 27 09Document6 pagesAutismMotorSkillEvaluationFINALBESt028.8 27 09Shayne Tee-MelegritoNo ratings yet

- R It by Brooke IngersollDocument16 pagesR It by Brooke IngersollJuliana BravoNo ratings yet

- Sensory Profile: Submitted By-Amandeep Kaur M.O.T-Neuro, Sem 3 ENROLLMENT NO - A138141620004 Guided by - Ruby Ma'AmDocument42 pagesSensory Profile: Submitted By-Amandeep Kaur M.O.T-Neuro, Sem 3 ENROLLMENT NO - A138141620004 Guided by - Ruby Ma'Amamandeep kaur100% (1)

- Kathryn Edmands The Impact of Sensory ProcessingDocument26 pagesKathryn Edmands The Impact of Sensory ProcessingBojana VulasNo ratings yet

- TACTILE AND PROPRIOCEPTIVE INTERVENTIONDocument13 pagesTACTILE AND PROPRIOCEPTIVE INTERVENTIONAnup Pednekar100% (1)

- The Effect of A Two-Week Sensory Diet On Fussy Infants With Regulatory SensDocument8 pagesThe Effect of A Two-Week Sensory Diet On Fussy Infants With Regulatory Sensapi-238703581No ratings yet

- Allen Cogntive Disabilties ModelDocument29 pagesAllen Cogntive Disabilties ModelSarah Lyn White-Cantu100% (1)

- Occupational Therapy Sensory Integration Protocol For Early InterDocument56 pagesOccupational Therapy Sensory Integration Protocol For Early Intermanali vyasNo ratings yet

- Fine Motor and Handwriting Skills ActivitiesDocument4 pagesFine Motor and Handwriting Skills Activitiesehopkins5_209No ratings yet

- Caregiver Sensory ProfileDocument6 pagesCaregiver Sensory ProfileRomysah Farooq100% (1)

- Sensory Diet Sample FormatDocument1 pageSensory Diet Sample FormatBernard CarpioNo ratings yet

- Azzam Scale in Practical Guide of Occupational TherapyFrom EverandAzzam Scale in Practical Guide of Occupational TherapyNo ratings yet

- Sensorimotor History Questionnaire For Parents of PreschoolDocument77 pagesSensorimotor History Questionnaire For Parents of Preschoolscribdmuthu100% (2)

- Infant Toddler Sensory Profile Assessment GuideDocument21 pagesInfant Toddler Sensory Profile Assessment GuideFedora Margarita Santander CeronNo ratings yet

- Sensory Integration: A Practical Look at The Theory and Model For Intervention by Megan Carrick, MOTR/LDocument6 pagesSensory Integration: A Practical Look at The Theory and Model For Intervention by Megan Carrick, MOTR/LautismoneNo ratings yet

- CHAPTERIDocument13 pagesCHAPTERIGuess WhoNo ratings yet

- Samsung Marketing Strategy ThesisDocument7 pagesSamsung Marketing Strategy Thesisdeborahquintanaalbuquerque100% (2)

- Teacher EducationDocument112 pagesTeacher EducationhurshawkNo ratings yet

- Sample Research ProtocolDocument5 pagesSample Research Protocollpolvorido100% (1)

- Thesis Sa PagnenegosyoDocument6 pagesThesis Sa PagnenegosyoBuyACollegePaperSingapore100% (2)

- Guidelines For Smart Grid Cyber Security: Vol. 2, Privacy and The Smart GridDocument69 pagesGuidelines For Smart Grid Cyber Security: Vol. 2, Privacy and The Smart GridInterSecuTechNo ratings yet

- The Complete List of Branding Services and Deliverables - CannyDocument15 pagesThe Complete List of Branding Services and Deliverables - CannyBGC MarcomNo ratings yet

- Mallory Brown: (727) 742-9743 - Brown - Mall@husky - Neu.eduDocument1 pageMallory Brown: (727) 742-9743 - Brown - Mall@husky - Neu.eduapi-455273982No ratings yet

- EU-SPRI Conference Proceedings Risk Climate Innovation LinkDocument7 pagesEU-SPRI Conference Proceedings Risk Climate Innovation LinkMD. Naimul Isalm ShovonNo ratings yet

- THR Rolr Halal Science (Aliyah)Document22 pagesTHR Rolr Halal Science (Aliyah)Maisaroh AliyahNo ratings yet

- Trying Lemongrass As Organic Mosquito RepellentDocument41 pagesTrying Lemongrass As Organic Mosquito RepellentSan Shine100% (1)

- ARDI Actors Resources Dynamics I PDFDocument14 pagesARDI Actors Resources Dynamics I PDFMarcela BasurtoNo ratings yet

- A Study On Budgetory ControlDocument39 pagesA Study On Budgetory ControlStella PaulNo ratings yet

- I and S - Guide New-2014-15Document69 pagesI and S - Guide New-2014-15Llama jennerNo ratings yet

- Eco TectureDocument20 pagesEco TectureMichael Jherome NuqueNo ratings yet

- Moreno MethodologyDocument97 pagesMoreno MethodologyUyên TrươngNo ratings yet

- Group 1 Rose Research JournalDocument8 pagesGroup 1 Rose Research JournalJoyce NoblezaNo ratings yet

- Photo-Elicitation Interview - 2004-Clark-IbáÑez-1507-27Document21 pagesPhoto-Elicitation Interview - 2004-Clark-IbáÑez-1507-27Fidel Terenciano FilhoNo ratings yet

- Rendang Malaysia - Culinary Heritage and Cultural IdentityDocument2 pagesRendang Malaysia - Culinary Heritage and Cultural Identitynajwalai98No ratings yet

- Template of JournalDocument6 pagesTemplate of JournalArisYamanNo ratings yet

- Vels University MBA Logistics & Shipping Management Program OutcomesDocument116 pagesVels University MBA Logistics & Shipping Management Program OutcomesDhanashekar NaiduNo ratings yet

- Boncodin MatrixDocument3 pagesBoncodin Matrixlindsay boncodinNo ratings yet

- Book Catalogue 2021Document79 pagesBook Catalogue 2021navecNo ratings yet

- Challenging ocular architecture with multi-sensory designDocument4 pagesChallenging ocular architecture with multi-sensory designayush datta100% (1)

- Babixxx 170713 1Document12 pagesBabixxx 170713 1Nelson PutraNo ratings yet

- Population and SampleDocument10 pagesPopulation and SampleTata Intan TamaraNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PROPOSAL FORMAT - June 20 2023Document5 pagesRESEARCH PROPOSAL FORMAT - June 20 2023Saikawa YuukiNo ratings yet

- Inventory Control Methods for Apparel IndustryDocument3 pagesInventory Control Methods for Apparel IndustryARPITA PATHYNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Strategic Planning and PerformanceDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Strategic Planning and Performancec5qvf1q1No ratings yet

- BRUNBORG Et Al-2011-Journal of Sleep ResearchDocument7 pagesBRUNBORG Et Al-2011-Journal of Sleep ResearchAndhika CahyaNo ratings yet