Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ABG Journal

Uploaded by

speedmindOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ABG Journal

Uploaded by

speedmindCopyright:

Available Formats

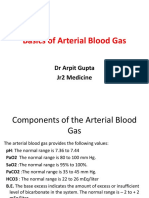

Arterial Blood Gases and Pulmonary Function

Testing in Acute Bronchial Asthma

Predicting Patient Outcomes

Richard M. Nowak, MD; Michael C. Tomlanovich, MD; Diane D. Sarkar, MD;

Paul A. Kvale, MD; John A. Anderson, MD

Pretreatment and posttreatment arterial blood gas and pulmonary drawn anaerobically from the radial

function testing measurements were prospectively compared as to their artery into a heparinized glass syringe

ability to assess asthma severity accurately and, thus, predict the outcome in while the patient was at rest and breath¬

102 episodes of acute bronchial asthma initially seen in the emergency ing room air. It was then analyzed for

department. The Pao2, Paco2, or pH was unable to separate these patients Pa02, PaC02, and pH.

Uniform therapy consisted of terbuta-

requiring admission from those that could be confidently discharged, while line sulfate, 0.25 mg subcutaneously, and,

the 1-s forced expiratory volume (FEV,) and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) if clinically necessary, intravenous amino-

did so both before and after treatment. Furthermore, virtually all patients phylline with a 5.6-mg/kg loading dose

with hypercarbia (Paco2 >42 mm Hg) and/or severe hypoxemia (Pao2 <60 (downwardly adjusted with recent oral

mm Hg) had a PEFR below 200 L/min, or an FEV, below 1.0 L. Thus, selective theophylline therapy) and a 0.9-mg/kg/hr

use of arterial blood gas analysis should substantially decrease both maintenance infusion.'0 Any further thera¬

diagnostic cost and patient discomfort without jeopardizing health care. py was left to the discretion of the emer¬

(JAMA 1983;249:2043-2046) gency medicine physician. Repeated

PEFR, FEV„ and arterial blood gas mea¬

surements while breathing room air were

MEASUREMENTS of arterial blood possible, specific pulmonary function obtained before the patient's discharge or

admission to the hospital. In virtually all

gas tensions are widely recommended testing guidelines for a more selective

cases, three PEFR and FEV, measure¬

in the assessment and treatment of useof blood gas analysis to identify ments were obtained and the best value

asthmatic patients in the emergency hypercarbia and/or severe hypoxe¬ was recorded.

department13 despite a rather poor mia. Decisions to admit or discharge patients

correlation between gas tensions and were based on clinical assessment and,

asthma severity as measured by pul¬ PATIENTS AND METHODS

occasionally, FEV, measurements." We

monary function testing.4'8 Patients between the ages of 16 and 40 did not use the PEFR in decision making.

This study was undertaken (1) to years who were seen in the emergency All percent-of-predicted normal values

prospectively compare the specificity department with acute bronchospasm were calculated after the study was com-

of pretreatment and posttreatment when one of the investigators was present pleted.'2'1 At the conclusion of the study,

arterial blood gas analysis with pul¬ and who fulfilled the criteria for asthma the patients were divided into three cate¬

as defined by the American Thoracic Soci¬ gories. Group 1 included all those who

monary function testing in predicting ety' were uniformly included into the were admitted to the hospital, while

patient outcome and (2) to develop, if study. Any patient with any cardiac or groups 2 and 3 included those who were

other lung disease was excluded. Peak sent home. Each discharged patient was

From the Divisions of Emergency Medicine (Drs expiratory flow rate (PEFR) measure¬ interviewed in the emergency department

Nowak, Tomlanovich, and Sarkar), Pulmonary Medi- ments, using a mini-Wright peak flow- or by telephone 48 hours later, and a

cine (Dr Kvale), and Allergy and Immunology (Dr

meter, and then spirometry (1-s forced questionnaire (Fig 1) was completed to

Anderson), Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit.

Reprint requests to Division of Emergency Medi- expiratory volume [FEV,]), using a single- determine the outcome. Group 2 patients

cine, Henry Ford Hospital, 2799 W Grand Blvd, wedge bellows spirometer, were performed had two or more affirmative answers,

Detroit, MI 48202 (Dr Nowak). before any treatment. Arterial blood was while discharged patients with fewer than

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on November 25, 2009

two affirmative answers were placed in similarly poor correlation (correla¬ for individual percent-of-predicted

group 3. The objective accuracy of this tion coefficient, .4426) was found in FEV, values. Note that C02 retention

questionnaire has been previously veri¬ comparing the posttreatment Pao, (>42 mm Hg) occurred only with an

fied.14 and the percent-of-predicted FEV,.

The data were analyzed using two-

FEV, below 25% of the predicted

The pretreatment Paco2 is com¬ value. A posttreatment comparison of

sample t tests to examine the pretreat- with the percent-of-predicted

ment and posttreatment differences pared these variables showed a far worsen¬

among the three groups. Relationships FEV, for all patients in Fig 2 (corre¬ ing correlation (correlation coeffi¬

between the PEFR or FEV, and the Pao; lation coefficient, —.5337). There was cient, -.0199).

and PacOj measurements were examined likewise a wide variation in the Paco2 All patients with a pretreatment

by means of correlation coefficients.

RESULTS Is your asthma worse now than when you left the emergency room?

Eighty-six patients, 54 women and Yes No

32 men, were treated for 102 episodes

of acute asthma. The mean age was

25.1 years and the mean duration of Have you had to return to any emergency room or see another doctor?

therapy in the emergency department

was 4.8 hours, with no statistically Yes No

significant group differences. Thirty-

two patients (31.4%) were admitted Has your asthma kept you awake at night since you left our emergency room?

(group 1); 20 patients (19.6%) were

discharged but with further respira¬ Yes No

tory problems (group 2); and 50

(49.0% ) were discharged without sub¬ Has your breathing prevented you from resuming your usual activities?

sequent problems (group 3). Some

Yes No

patients refused to allow drawing of

blood for repeated determination of

arterial blood gas values at the cessa¬ Fig 1.—Questionnaire used in studying patients 48 hours after discharge from emergency

tion of treatment, and the mini- department.

Wright peak flowmeter was unavail¬

able for a short portion of the study. Table 1.—Comparison of Mean Pretreatment Arterial Gas Analysis

These factors explain the small dif¬ and Pulmonary Function Testing Measurements

ference in the number of patients

with FEV, and PEFR measurements No. of

1-s Forced Expiratory Volume

Pao„ Paco,,

and in the number in the pretreat- Group Cases mm Hg* mm Hg* pH* Absolute, Lt % of Predicted!

ment and the posttreatment phases of 1 32 68.4 ±8.8 36.3 ±5.9 7.39 ±0.05 0.68 20.1

this study. The mean pretreatment 2 20 71.7±8.7 34.5±7.2 7.40±0.05 0.86 25.3

3

Pao2, Paco2, pH, FEV,, and PEFR for 50 71.5± 12.0 35.8±6.9 7.41 ±0.05 1.12 33.4

all groups are shown in Table 1. There Peak Expiratory Flow Rat«

was no statistically significant group Absolute, L/ mint % of Predicted!

difference between any of the arterial 1 30 68.4±8.8 36.3±5.9 7.39±0.05 134.3 30.3

blood gas variables, whereas both the 2 20 71.7±8.7 34.5±7.2 7.40±0.05 128.0 29.3

3 48 71.9±12.1 35.5±6.6 7.41 ±0.05

FEV, and PEFR were able to separate 176.2 39.7

accurately group 1 from group 3 *Mean±SD. All P>05, two-sample /test, in comparison of groups.

tAll P > 05. two-sample /test, except as indicated.

patients. Similarly, the mean post- $P<05.

treatment Pao2, PaC02, pH, FEV,, and

PEFR are shown in Table 2. Again,

there was no statistically significant Table 2.—Comparison of Mean Posttreatment Arterial Gas Analysis

group difference between any of the and Pulmonary Function Testing Measurements

arterial blood gas measurements,

1-s Forced Expiratory Volume

whereas there were statistically sig¬ No. of Pao„ PacOj,

nificant differences in the pulmonary Group Cases mm Hg* mm Hg* pH* Absolute, Lt % of Predlctedt

1 28 75.3±11.6 30.9 ±3.8 7.45 ±0.04 1.02

function tests (both the FEV, and 32.1

2 13 80.2±10.9 31.5±4.5 7.44±0.03 1.60 49.6

PEFR were able to distinguish accu¬

3 44 78.0±12.7 32.3±4.5 7.43±0.04 2.16 62.5

rately groups 1 and 2 patients from Peak Expiratory Flow Rate

group 3 patients).

A comparison of the pretreatment Absolute, L/mlnt % of Predlctedt

1 28 75.3±11.6 30.9±3.8 7.45±0.04 186.6 42.9

Pa02 and the percent-of-predicted 2 81.0±10.9 31.7±4.7 216.7 52.2

12 7.44±0.02

FEV, for all patients showed a corre¬ 3 41 77.5± 13.0 32.4±4.6 7.43±0.04 322.7 71.7

lation coefficient of .4134, with wide

variations in the Pao2 for individual *Mean±SD. All P>05, two-sample ttest, in comparison of groups.

tAII P<05, two-sample ftest, except as indicated.

percent-of-predicted FEV, values. A *P>05.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on November 25, 2009

55

PaCOj above 42 mm Hg and/or a Pa02

below 60 mm Hg are shown in Table

3. As might be expected, a higher

50

percentage of these patients were in

group 1. It is noteworthy, however,

that 16% of all group 3 patients had 45 I

pretreatment hypercarbia and/or se¬

vere hypoxemia. Virtually all of these

patients could be detected by specific 40 • MS *|

pulmonary function testing guide¬

lines (Table 4). These included an

absolute FEV, below 1.0 L or a PEFR 35

below 200 L/min.

The pretreatment-to-posttreatment .

• • •

change in Pao, as compared with that 30

for FEV, is seen in Fig 3 (correlation

coefficient, .1824). There was a wide

fluctuation in the degree of improve¬ 25 • •

ment in the Pa02 with specific

improvements in the FEV,. Also, 20 I

there were a number of patients (13/

79, or 17%) with a variable decrease 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

in the Pao2 accompanied by an obvi¬ %-of-Predicted FEV,

ous rise in the FEV,.

The pretreatment-to-posttreatment Fig 2.—Comparison of pretreatment Paco2 and percent-of-predicted 1-s forced expiratory

volume (FEV,) in groups 1 (squares), 2 (triangles), and 3 (circles). Numbers indicate more than

one value at same location.

Table 4.—Pulmonary Function Criteria Identifying All Cases

Table 3.—Pretreatment Hypercarbia of Hypercarbia* and Severe Hypoxemiatt

and/or Severe Hypoxemia

%-of-Pr»dlct«d

No. (%) of Patients

_Absolute Value_Normal Value

1-s forced expiratory volume <1.0L <25

Paco, Pao,

Group >42 mmHg <60 Hgmm Peak expiratory flow rate_<200 L/min_<30

1 8/32(25) 5/32(16)

2 2/20(10) •Paco,, greater than 42 mm Hg.

2/20(10) fPao,, less than 60 mm Hg.

3 8/50(16) 8/50(16) tone group 3 patient was the exception, exceeding these guidelines but with a Pao, of 56 mm Hg.

Fig 3.—Relationship of pretreatment-to-posttreatment change in Pao, Fig 4.—Relationship of pretreatment-to-posttreatment change in Paco,

and 1-s forced expiratory volume (FEV,). Numbers indicate more than and 1 -s forced expiratory volume (FEV,). Numbers indicate more than

one value at same location. one value at same location.

35

10

30 x

X 6 XX X

25 X XXX

X

x.. x

20 XX

.Sx_ X X XXX

I XXX

I X XX

15 52XX xx x x x X X

s -6

XX X2

5

10 i 2 X

XX

XXX

X

XX

X X

-10

22 X x

5 X X X XX X

! xx Sx -14

Jexxx X

0

-T~"","~*—-x-x--

x

-18

I im

I X

-5t X

-22

X

-10 I »

-26

-15 -30 -I

I I I

-0.6 0 0.6 1.4 2.2 3.0 -0.6 0 0.6 1.4 2.2 3.0

-1.0 -0.2 0.2 1.0 1.6 2.6 -1.0 -0.2 0.2 1.0 1.8 2.6

Change in FEV,, L Change in FEV,, L

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on November 25, 2009

change in PaC02 is compared with nary function testing and clinical out¬ have elevation of the Paco2. Sole

that for FEV, in Fig 4 (correlation come. reliance on arterial blood gas analysis

coefficient, —.0821). There was an Extreme airway obstruction and/or in these patients would underesti¬

inconsistent increase or decrease in fatigue, however, may be associated mate the severity of the degree of

the Paco2 with specific improvements with eventual elevation of the Paco2 airway obstruction.

in the FEV,. Also, 17 patients had and a correspondent worsening of The change in Pao2 or PaC02 does

improved their FEV, (0 to 1.8 L) but arterial hypoxemia. The specific pul¬ not accurately reflect change in pul¬

had virtually unchanged Paco2 val¬ monary function criteria (Table 4) monary function testing. Indeed,

ues. that will indicate those patients at some patients, despite improved air

risk include an absolute FEV, below flow with treatment, exhibit a tran¬

COMMENT 1.0 L or a PEFR below 200 L/min. sient worsening of their hypoxemia.

Many have advocated the useful¬ Sixteen percent of patients who did This is thought to be secondary to the

ness of arterial blood gas analyses in well after discharge from the emer¬ dilation of previous constricted pul¬

acute bronchial asthma to objectively gency department had come there monary vessels produced by sympa-

stage severity," despite the lack of with hypercarbia and/or severe hy¬ thomimetics and/or theophylline.15'6

verification of their value. This stag¬ poxemia. There is no question that Thus, repeated arterial blood gas

ing system grades asthma severity these patients had initially severe analysis in those patients, improving

based on the degree of hypoxemia and asthma, but the most important man¬ to an FEV, above 1.0 L or a PEFR

hypocarbia or hypercarbia. Our data, agement consideration was the degree above 200 L/min, is of no value in

and those of others,"8 have consistent¬ of reversibility of the attack. If these further assessment of asthma severi¬

ly shown a relatively poor correlation patients have specific improvement in ty.

between the percent-of-predicted their pulmonary function testing In summary, arterial blood gas

FEV, and the Pao2 or the Paco2. (posttreatment PEFR above 300 L/ analysis correlates poorly with pul¬

Furthermore, we have shown (Tables min or FEV, above 2.1 L), they may be monary function testing and is thus

1 and 2) that the mean Pa02, PaC02, confidently discharged from the of little predictive value in determin¬

and pH in each of our three clinical emergency department.1,1 Also, once ing patients' outcome. Hypercarbia

outcome groups were not statistically the FEV, is above 1.0 L or the PEFR and/or severe hypoxia is seen only in

different. The PEFR and the FEV,, above 200 L/min, there is no need for patients exhibiting specific pulmo¬

however, have consistently discrimi¬ repeated arterial blood gas analysis. nary function testing abnormalities.

nated among these same clinical Furthermore, there were 43 pa¬ These include an FEV, below 1.0 L

groups. Thus, arterial blood gases are tients with severe impairment in pul¬ (25% of predicted value) or a PEFR

not absolutely reflective of asthma monary function (FEV,, <25% of below 200 L/min (30% of predicted

severity when compared with pulmo- predicted value, Fig 2) who did not value).

References

1. Nardell EA, Slate JL, Westphal DM, et al: 51:788-798. 12. Morris JF, Koski A, Johnson LC: Sprio-

Asthma, in Wilkins EW, Dineen JJ, Moncure AC 7. Kelsen et al:

SG, Kelsen DP, Fleegler BF, metric standards for healthy nonsmoking adults.

(eds): Massachusetts General Hospital Textbook Emergency room assessment and treatment of Am Rev Respir Dis 1971;103:57-67.

of Emergency Medicine. Baltimore, Williams & patients with acute asthma. Am J Med 1978; 13. Cherniack RM, Raber MB: Normal stan-

Wilkins Co, 1979, pp 138-145. 64:622-628. dards for ventilatory function using an auto-

2. Ungar JR: Respiratory emergencies associ- 8. Murray AB, Hardwick DF, Pirie GE, et al: mated wedge spirometer. Am Rev Respir Dis

ated with bronchial asthma, in Schwartz GR, Assessing severity of asthma with Wright peak- 1972;106:38-46.

Safar P, Stone JH, et al (eds): Principles and flow meter. Lancet 1977;1:708. 14. Nowak RM, Pensler ML, Sarkar DD, et al:

Practices of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, 9. American Thoracic Society: Chronic bron- Comparison of peak expiratory flow and FEV,

WB Saunders Co, 1978, pp 862-867. chitis, asthma, and pulmonary emphysema: A admission criteria for acute bronchial asthma.

3. McKenzie SA, Edmunds AT, Godfrey S: statement by the Committee on Prognostic Stan- Ann Emerg Med 1982;11:64-69.

Status asthmaticus in children. Arch Dis Child dards in Non-tuberculous Respiratory Disease. 15. Rees HA, Millar JS, Donald KW: A study

1979;54:581-586. Am Rev Respir Dis 1962;85:762-768. of the clinical course and arterial blood gases of

4. McFadden ER, Lyons HA: Arterial blood 10. Piafsky KM, Ogilvie RI: Dosage of theo- patients in status asthmaticus. Q J Med 1968;

gas tension in asthma. N Engl J Med 1968; phylline in bronchial asthma. N Engl J Med 148:541-561.

278:1027-1032. 1975;292:1218-1222. 16. Read J, Tai E: Response of blood gas

5. Tai E, Read J: Blood-gas tensions in bron- 11. Nowak RM, Gordon KR, Wroblewski DA, tensions to aminophylline and isoprenaline in

chial asthma. Lancet 1967;1:644-646. Spirometric evaluation of acute bronchial

et al: patients with asthma. Thorax 1967;22:543-549.

6. Rebuck AS, Read J: Assessment and man- asthma. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians 1979;

agement of severe asthma. Am J Med 1971; 8:9-12.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on November 25, 2009

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- PLT COLLEGE, InC. Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya InstituteDocument5 pagesPLT COLLEGE, InC. Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya Instituteannailuj30No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Penetrating TraumaDocument606 pagesPenetrating TraumaMajdEddeinAlmustafaNo ratings yet

- 31 Acid Base Imbalances ABGs II - 230110 - 004938Document2 pages31 Acid Base Imbalances ABGs II - 230110 - 004938JanaNo ratings yet

- RESPIRATORYDocument10 pagesRESPIRATORYVikash Kushwaha100% (2)

- NCLEX Questions PulmDocument27 pagesNCLEX Questions PulmAnthony Hawley100% (2)

- Chest Injury: College of Nursing Valenzuela Campus 120 Macarthur Highway, Marulas, Valenzuela CityDocument10 pagesChest Injury: College of Nursing Valenzuela Campus 120 Macarthur Highway, Marulas, Valenzuela CityDump Cherry33% (3)

- Respiratory Disorders NCLEX ReviewDocument22 pagesRespiratory Disorders NCLEX ReviewPotchiee Pfizer50% (2)

- 4 - ClinicalDocument11 pages4 - Clinicalapi-464332286100% (1)

- Pneumonia QuizDocument7 pagesPneumonia QuizJennah JozelleNo ratings yet

- Set 1 PDFDocument62 pagesSet 1 PDFAlyssa MontimorNo ratings yet

- ExcretaDocument1 pageExcretaspeedmindNo ratings yet

- Post Op BedDocument4 pagesPost Op BedspeedmindNo ratings yet

- Meds in MentalDocument4 pagesMeds in MentalspeedmindNo ratings yet

- Meds in MentalDocument4 pagesMeds in MentalspeedmindNo ratings yet

- Meds in MentalDocument4 pagesMeds in MentalspeedmindNo ratings yet

- Post Op BedDocument4 pagesPost Op BedspeedmindNo ratings yet

- ER NurseDocument3 pagesER NursespeedmindNo ratings yet

- Acid base disorders simplified/TITLEDocument48 pagesAcid base disorders simplified/TITLEAGUNG SETIADI NUGROHONo ratings yet

- Acid - Base BalanceDocument41 pagesAcid - Base BalanceEgun Nuel DNo ratings yet

- ArpitDocument73 pagesArpitDurgesh PushkarNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Nursing A Concept Based Approach To Learning Volume 2 1 Edition NcclebDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Nursing A Concept Based Approach To Learning Volume 2 1 Edition Ncclebmono.haiduck6htcr8100% (42)

- Stability of PH, Blood Gas Partial Pressure, Hemoglobin Oxygen Saturation Fraction, and Lactate ConcentrationDocument9 pagesStability of PH, Blood Gas Partial Pressure, Hemoglobin Oxygen Saturation Fraction, and Lactate ConcentrationJavier DeinecaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Neuro ProtectionDocument7 pagesClinical Neuro Protectionlakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Nursing Practice IvDocument24 pagesNursing Practice IvJohn wewNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Autumn ConwayDocument7 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Autumn ConwayCharlyn JenselNo ratings yet

- R-BrainRT Software For Philips IntelliVue-1-1Document5 pagesR-BrainRT Software For Philips IntelliVue-1-1camilo escobedoNo ratings yet

- Arterial Blood Gas InterpretationDocument9 pagesArterial Blood Gas InterpretationSunny AghniNo ratings yet

- Reflection of Lab VisitDocument15 pagesReflection of Lab VisitM Asif NawazNo ratings yet

- Pneumo Tot MergedDocument103 pagesPneumo Tot MergedAndra BauerNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Nursing Questions Bank and Model AnswersDocument70 pagesCritical Care Nursing Questions Bank and Model AnswersHusseini ElghamryNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Clinical Education: Interpretation of ABGsDocument8 pagesCritical Care Clinical Education: Interpretation of ABGsRumela Ganguly ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Worksheet Packet May 2023Document50 pagesWorksheet Packet May 2023Julie AnnNo ratings yet

- Arterial Blood Gas UpdatedDocument30 pagesArterial Blood Gas UpdatedMoustafa IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Effect of PEEP On Dead Space in An Experimental Model of ARDSDocument10 pagesEffect of PEEP On Dead Space in An Experimental Model of ARDSFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- I-Smart - Care 10 - 2022Document2 pagesI-Smart - Care 10 - 2022nguyen minhNo ratings yet

- Case 5 - (Salimbagat) Diagnostic and Laboratory ProceduresDocument12 pagesCase 5 - (Salimbagat) Diagnostic and Laboratory ProceduresChristine Pialan SalimbagatNo ratings yet

- Slide Kuliah Gagal Nafas-AgdDocument78 pagesSlide Kuliah Gagal Nafas-Agdeko andryNo ratings yet