Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Global Warming Impact On Uganda - Integral Farm-Household Management

Uploaded by

GiaToula54Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Global Warming Impact On Uganda - Integral Farm-Household Management

Uploaded by

GiaToula54Copyright:

Available Formats

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

Integral Farm-Household Management for Food Security & Sustainable Livelihoods in

Uganda by Elijah Kyamuwendo(ı) and E. John Wibberley(²).

1

CEO of Kulika Trust, Uganda and Farmer in Mubende, Uganda.

2

Professor of Agriculture, Royal Agricultural College Cirencester, UK and team member of RURCON Africa.

IFMA 17 (2009) Illinois, USA : Agriculture: Food, Fiber and Energy for the Future :

Abstract

Integral Farm-Household management involves learning and adopting appropriate resource-

using techniques both on farmland and in the associated households. Significantly, as elsewhere

among longstanding rural communities, in rural Africa there is no separation between home and

work; both environments merge. Typically, policy-makers seek ‘single issue’, easily measurable

solutions to rural development challenges. Field realities are more complex involving many inter-

related factors if both food security and sustainable livelihoods are to be achieved. This paper

reports one such training and implementation case study from Uganda where integral

management (blending all relevant resources to deliver sustainablity) is being attempted. The

CADeP (Congregational Agricultural Development Programme) began in 2005 and extended at

the time of this research in 2008 to 31 farms situated in central, eastern, south-western, western

and north-western Uganda.

Introduction

Integral management is the art of blending all resources relevant to a sustainable future into a

strategy for pragmatic implementation. Press (1980) defined management as ‘the greatest of the

arts, since its medium is human talent itself.’ While there are certain scientific (or logically

sequenced) approaches – such as management by objectives - that can be taken, neither

management nor economics should be treated as equivalent to the physical sciences (Soros,

2008). The danger of doing so is that management becomes specific and target-oriented such that

policy-makers seek so-called ‘silver bullet’ solutions to realities that focus on a single factor as an

attempted corrective to problems. This is analogous to the kind of cropping trials that simply vary

the input of a single nutrient, with all other factors kept as constant as possible. Conversely, as

pointed out by Turner & Wibberley (2009) ‘integral management attempts to deal with reality

holistically. It is applied to real resources of land/nature, labour, capital and entrepreneurship

blended to secure a sustainable future. The management process must creatively balance these

resources in order to reflect the complex and comprehensive character of sustainability. This is an

art! It is also an applied science in that it depends on systematic measurement and analysis of real

resources and their subsequent recombination in a planned way to achieve agreed objectives (the

integral components of sustainability).’

Sustainability incorporates the range of factors listed in Fig.1. The concept of sustainability might

best be encapsulated as ‘for the grandchildren’. Thus, the farm manager must ‘not only look after

the day-to-day farm work but also take care of the long term interests of the farm for future

generations’ (Joy & Wibberley, 1979). Such integral management requires simultaneous attention

to the essentials for a sustainable future proposed by Wibberley (1989) viz:- ecology, economy,

energy-efficiency, employment, equity and ethics. Ethics integrates all the previous five aspects;

what is good, right and fair must take account of all these variables.

July 2009 292

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

2

Fig.1. Components of Sustainability

GRANDCHILDREN – intergenerational inheritance

RELATIONSHIP CONSERVATION – rural community life and values

LOCAL SELF-RELIANCE – indigenous technical knowledge and skills

PRODUCTIVITY - to meet present and future needs of the population

PROFITABILITY – to enable investment for future caring and sharing

RELIABILITY – consistency of performance under varying conditions

RESILIENCE – flexibility to withstand and adapt to constraints

APPROPRIATENESS OF TECHNIQUES – to both user and environment

REPLENISHMENT OF RENEWABLE RESOURCES – avoiding exhaustion

PROVISION OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICES – water, carbon-sink, tranquillity

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION – against erosion and pollution

BIODIVERSITY MAINTENANCE – of both wild and farmed species

ADAPTABILITY – to changing global circumstances, including climate change

In countries such as Uganda with a predominantly small and family farm structure, the farm itself

cannot be seen in isolation as a business separate from the homestead. Neither can agriculture be

developed internationally in isolation from the considerations of the whole planet as the habitat of

humanity. Thus the approach of Farming Systems Development (FSD) proposes the basic unit as

the Farm-Household (FAO, 1989).

Integral management for sustainability with the Farm-Household as the basic unit offers the

guiding principle for the CADeP (Congregational Agricultural Development Programme) and its

impacts to date (2005-2008), which are here summarised as a case study.

Uganda land, population and food

Some 982 million people world-wide were reckoned as food insecure in 2007 and this number,

contrary to Millennium Development Goal 1 (‘Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger’), is likely

to rise to 1.2 billion by 2017 (USDA, 2008). Uganda, which had a population around 7 million at

independence in 1962, had around 31 million or more by 2008 and, at the present growth rate of

3.6% per annum, is predicted by the UNDP to reach 130 million by 2050. There are already some

1.7 million Ugandans who are reckoned food insecure. Of these, some 1.2 million are in the

conflict-torn Northern region, some 0.275 million in drought-affected Karamoja (NE) and around

0.2 million affected by floods between these two zones (Mukalazi, 2008 – USAID data).

Apparent climate change impacts pose huge additional challenges involving mitigation and

adaptation to pursue Uganda’s agricultural output requirements for food security (Mortimore &

Manvell, 2006).

Food Security is the relative availability of dietary requirements that are accessible, affordable

and attainable avoiding hazards. Of course, the highest degree of food security might be

associated with growing all of one’s own family and community needs as locally as possible so

that transport costs and possible interruptions of supply chains are avoided or minimised.

Already, increasing urbanisation means that food has to be transported from further rural areas,

July 2009 293

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

3

although internationally there are futuristic moves to grow foods from microbiological sources

and other ‘factory-farmed’ multi-storey units in cities. Attainment of food security and

sustainable livelihoods more conventionally using farmland are urgent for Uganda. These are the

key goals of CADeP.

Background to CADeP

CADeP, the Congregational Agricultural Development Programme, began in 2005 among

communities of religious Brothers and Sisters of the Roman Catholic Church in Uganda. It

involves training in Sustainable Organic Agriculture (SOA) and provision of inputs to improve

agricultural practices and farm-household facilities. In mid-2008, 78 had completed training.

Training and extension liaison is delivered by Kulika Trust, Uganda, an NGO with 25 years

practical experience of field training and promotion of SOA and improved household

technologies. Kulika Trust, Uganda supports community development initiatives, education

programmes and related research. In 2008, since its inception in 1983, 1512 students had become

professionals through Kulika’s educational scholarships and over 7000 farmers have improved

livelihoods as a result of Kulika training (Kyamuwendo, 2008). Kulika staff provide CADeP

training. Training and extension itself needs to be provided in a sustainable way (Wiibberley,

1997, 1998; Kyamuwendo, 1999).

As well as practical, farm-based skills training, CADeP offers material items such as tools,

workers’ housing and 10,000-litre water tanks. Material items offered through CADeP are

crucially synergistic to attainment of goals for adoption of the training in order to achieve food

security and to promote sustainable livelihood income generation. Funding is from The

Netherlands. CADeP is run by a 6-member Core Team. In order to promote local sustainability of

mutual learning among farmers, development is envisaged of FARMS - Farm Asset Resource

Management Study - Groups (Wibberley, 1997; Kyamuwendo, 1999; Wibberley, 2008a).

Methodology

A participatory evaluation conducted during July 2008 (Wibberley, 2008b) involved all relevant

stakeholders including CADeP-trained people, farm workers, other community members,

neighbours, Superiors (Congregational overseers) and the Core Team of six managing CADeP. It

comprised visits to 31 farms of religious communities – 23 of Sisters and 8 of Brothers - on a

2,500-mile route around Uganda from central areas to Jinja in the east, to the south-west, western

and north-western areas (Gulu and Nebbi). Documents from CADeP were examined,

questionnaires analysed, interviews and discussions held, and many photographs taken.

The sequence at each visit (of typically 3+ hours) was:-

a) Greet and meet available members of the community and ask the local Superior and/or the

CADeP-trained member to provide background information using a proforma. This enabled us to

gain an overview as well as to establish a rapport with the respondent(s).

b) Request that one CADeP-trained person fill the farmers’ questionnaire, and the Superior

complete the appropriate management questionnaire while we visited the farm and farm

household facilities with another CADeP-trained person or member involved with the farm,

July 2009 294

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

4

together with key farm workers where possible. This procedure was essential to ensure we had

the information to take with us rather than relying on it being delivered later.

c) Farm visit taking photographs and recording observations, while also giving some input in

conjunction with the Kulika trainer so that we were not simply there extracting information

but also positively sharing ideas towards solving issues that concerned them.

d) A Group Exercise was carried out with any community members involved with farm work and

the farm workers themselves where possible. In practice, we were only able to apply this in part

and in some places not at all owing to the fact that many workers had not been in place long

enough or our visit did not coincide with an opportunity to meet them properly. However, we did

the exercise with over 130 farm workers.

We took at least a small meal at each place visited, and stayed overnight at four communities.

Improved land and natural resource management strategies

CADeP has had a huge impact on the adoption of soil conservation practices, including terracing,

use of cut-off ditches, L-bridges and planting of wash-stops. Some were known before CADeP.

However, the majority of the adoption of these practices has been after CADeP (Fig.2).

Fig. 2. Practices adopted before and after CADeP showing CADeP Impact.

Adopted before CADeP Adopted after CADeP

Plant tea use B Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Urine use B Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Compost Bbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Manure bbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Fodder cut bbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Mulching bbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Natural pes.* bbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Housing Liv. bbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Stoves bbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Records bbbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Bks./Acs bbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Discussions bbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Early plant’g bbbbbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Crop rotation bbbbbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Tree planting bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Oxen use bbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaa

Interplanting bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaa

Pray re farm bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaa

Aggregate bbbbbbbbb Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa + 68% after

Notes: * Natural pes. = natural pesticide use; Liv. = Livestock.

Soil amelioration and fertility-building practices have had immense benefit, including mulching,

compost-making, use of plant tea, proper manure collection for composting, and use of urine in

July 2009 295

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

5

both compost and the making of natural pesticides. Sack mounds, compost basket gardens, and

other vegetable growing techniques are widely used – including raised beds, table gardens,

passion-fruit trellises and plant nurseries.

Overall impacts of CADeP

The mean size of available land at the 31 farms was 240 acres (100 hectares) - some 7,500 acres

in all - with a mean area of 29 acres cultivated before CADeP and 48 acres afterwards, a 66%

mean increase in land utilisation. Resource management is much improved and better integrated.

Training has led to an increase in adoption of improved agricultural and farm-household practices

after CADeP, reported as +68% overall. Those trained are more confident and enjoy their

farming more. Some 35% began to pray specifically about their farming after CADeP. Some

practices, such as usage of plant tea, urine, manure collection, compost-making, fruit and

vegetable growing, have been massively adopted after CADeP, as have fuel-efficient stoves

(made from termite-mound soil moulded around banana stems) and tip-taps for household

hygiene. The Report (Wibberley, 2008b) reviews past training appreciation as well as future

training needs and shows that soil management, composting and cropping improvements have

been most valued while management topics such as farm planning and book-keeping, together

with animal health and husbandry are the most sought as follow-on teaching (Fig.3). Some local

workers have been motivated and engaged with the learning and adoption too – via participation

in week-long ‘caravans’ touring other farms to ‘look and learn’ about new techniques and their

impacts. At some places, micro-enterprises have begun with consequent livelihood enhancement.

Fig.3. Relative Usefulness of Topics in CADeP training received

Agricultural Skills

1st SOIL MANAGEMENT ###############################

2nd COMPOST-MAKING #######################

3rd CROPPING METHODS ################

4th WATER MANAGEMENT ##############

5th LIVESTOCK MANAGEMENT #############

Office/Management Skills

1st FARM PLANNING ###############################

2nd RECORD-KEEPING ######################

3rd BOOK-KEEPING & ACCOUNTS ###############

4th STORAGE/PROCESSING/MARKETg. ##############

5th TOOL CARE & INVENTORY #############

Impacts have not simply been quantitative in terms of more land cultivated and better yields

(matooke – green cooking banana - yields are reckoned to be 15-90% - mean 50% - better. Some

claim crop yields have doubled, trebled or more). Qualitative improvements concern better diets,

healthier communities and the widely evident conquest of food insecurity. The health benefits of

their more varied diet with vegetables (especially greens), fruits and juices, together with more

regular meals are universally acknowledged. This was evident not only from the meals we were

served during the evaluation but also from the demeanour of all we met. There is clear impact

July 2009 296

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

6

indicated by increased enjoyment from the improved understanding of their farm work with

better results from it. All testified to fewer days of sickness among their members. Furthermore,

savings on expenditure for bought-in food owing to expanded home production are greatly valued

by Congregational Superiors. However, there are challenges in persuading them that farms need

to retain some profits in order to reinvest and to maintain or upgrade their infrastructure.

Technical impacts include substantial increases in adoption of early planting (before the onset of

rains), of fruit trees, of crop rotation and of interplanting. Regularity of weed control was not

always as good as it could be and this will impact yields more than many other factors. Two key

imperatives of successful SOA are to keep weeds out and to get nutrients into the soil. These both

require adequate labour and effort. Labour shortage is a real constraint for some farms studied.

CADeP has stimulated better livestock husbandry but this area of work has much further to go

than the soil and cropping improvements seen. It is logical in SOA that one starts by improving

the soil and its cropping. Extra attention will be needed in the immediate future to livestock

management. Areas where CADeP has made a technical impact are in livestock housing, with

some impressive buildings seen. Along with this housing, adoption of fodder growing for zero-

grazing (using Napier grass and others) and proper watering practices are paramount. Apart from

proper rationing and controlled breeding, housing allows the collection of dung and urine and this

has been well adopted in places but not everywhere yet. On some farms, livestock management

was defective in terms of quality of housing, feeding, breeding control, and other signs of healthy

animal keeping. Given that 20 of the 31 farms have piggeries already, many wish to expand them

and others wish to start pig-keeping, there was a universal absence of crush bars seen in the pens

used for farrowing. This lack is resulting in much higher piglet mortalities than is necessary and

needs to be addressed urgently, as does the toughness of flooring used in many of the pens seen –

in order to lessen parasite risk, especially from Ascaris lumbricoides.

There is considerable scope for increased use of oxen and it is encouraging to see that CADeP is

making some impact here but there is far to go. In particular, the use of ox-carts for haulage could

be very strategic and hardly seems to have registered in the programme at farm level.

In the case of poultry, there is surprisingly little use of guinea fowls, which being indigenous to

Africa are rather better adapted than many poultry – and they are good alarm-raisers as security

against thieves, as are geese.

Farm Household Improvements

Rural households in Uganda can typically spend some 6 full-time person hours collecting water

each day, though this may often be done in teams (Kinyengere-Mango & Wibberley, 2006).

Furthermore, roof-water when not captured by guttering and water tanks causes immense erosive

damage to surrounding compounds. In this context, the CADeP emphasis on providing roof-

water tanks is extremely strategic. A few have added their own home-made solutions to capture

further water from additional roofs, or even from growing banana stems by bending backwards

the outer leaf sheath and catching the water so diverted in a drum. Bamboo is found but seldom

deliberately planted. Apart from providing for plant supports in gardens, larger bamboo is a

useful construction material for fences, shade roofs and furniture. The largest can be made into

July 2009 297

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

7

guttering for water capture and conveyance. This simple, renewable technology awaits

development within CADeP.

It is heartening to see the adoption of hygiene measures in the form of tip-taps almost

everywhere, some with the novel addition of a collecting bowl so that water used is not wasted

but can be put onto tree seedlings nearby. Drying racks for kitchen utensils, pots, plates and cups

are also widely used.

Though there are fuel-saving Larena and/or Ddembe stoves made at most places (84%) some are

not used regularly and there is still frequent co-existence of ‘3 stones’ cooking alongside

improved stoves. The reason for this given by many is that the 3 stones plus pot can be boiled

more quickly. The solution to this understandable but counterproductive thinking is:-

• to teach planning to start cooking earlier;

• to continue using the improved stoves (which get better with use);

• to extend the stove chimney so that it can draw better and thus heat quickly when needed;

• to develop the notion of heating control by means of woodash to damp down while using

temporarily restricted airflow at the entry point to speed up burning initially;

• to teach the improved nutritional value of slower cooking.

There is much scope to develop training on adding value and preventing waste through food

processing and preservation - notably using solar driers for surpluses (Namutebi et al, 2007).

Positive environmental impacts are potentially huge. Greater tidiness of compounds and their use

for demonstration of underutilised tree species and other improved practices could have

considerable future impact. Send-A-Cow in Uganda (www.sendacow.org.uk) has recently done

studies showing huge positive impacts of a single cow or dairy goat on Farm-Household System

vitality and viability – and in such integrated systems that the carbon-footprint (notably methane

+ manure) is offset by recycling, by growing fodder crops and by tree planting so that over 5

years it is 2.5 times positive! Alongside fuel-efficient moulded mud stoves, more tree planting is

also needed, as widely advocated and implemented in Kenya and elsewhere (Maathai, 2007).

Policy Implications, Discussion, Conclusions and Recommendations

CADeP merits not only continuation but initiation elsewhere in Uganda and beyond. The

combination of training, access to key material inputs and harnessing of existing resources

provides improvements that other ordinary farm-households can emulate. Expanded basic

training is warranted, and inclusion of more on livestock topics and on farm management for

those already trained. The programme needs to be rolled out to surrounding communities using

FARMS (Farm Asset Resource Management Study) Groups, training Community Animal Health

Workers (CAHWs) to give basic veterinary healthcare, and encouraging the formation of Junior

Conservation Societies with ‘Best-kept Village’ competitions to enhance habitats.

Improved analysis and use of records kept could be assisted by providing new proformas to ease

recording without creating unnecessary bureaucracy. Eventually, CADeP could have a bank of

data to be treated confidentially and used anonymously for comparing farm performance to

stimulate widespread agricultural improvement.

July 2009 298

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

8

Some farms are already producing not only matooke but also sweet bananas, bogoya bananas,

and plantains for roasting. Such diversification needs to be encouraged, as does planting of

sequential cabbages of different varieties. Marketing is vital with the warning caveat that - for

sustainable livelihoods with food security - farms should produce first for the local ‘family’, then

for proper animal feeding and only thirdly for the market.

Farmers appreciate CADeP training and positive impacts of its adoption on their livelihoods,

lifestyles and community relationships (Fig. 4). However, benefits can yet impact community

organisations more.

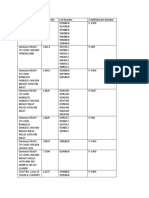

Fig. 4 . CADeP FARMERS’ OPINION SCORES : largely affirmative

KEY:- 5 = Strongly agree; 4 = Agree; 3 = Neutral; 2 = Disagree; 1 = Strongly disagree

4.7 : As a Farmer, I feel our CADeP programme really belongs to us Farmers

4.7 : As a Farmer, I intend to continue to use better farming after CADeP support ends

3.3 : CADeP requires too much attention to detail in farm management for my liking

4.1 : The thing I like most about CADeP is provision of training I can’t easily afford or get

4.8 : CADeP has helped me to become a better farmer

4.7 : CADeP has helped our household to gain better food security (some & to spare)

4.6 : CADeP has helped me enjoy the challenge of farming more & to trust God more

3.9 : CADeP has improved the balance of good relationships within my family

4.5 : CADeP has improved the balance of good relationships within our congregation

4.5 : CADeP has improved the balance of good relationships within our community

4.6 : CADeP has given me hope

4.5 : CADeP involvement has shown me the importance of training for livelihoods

4.7 : CADeP has enabled me take responsibility in my congregation

3.8 : CADeP has enabled me take responsibility in community organisations.

It is recommended that integral management is applied on farms for the simultaneous attainment

of the following six inter-related essentials for sustainable development, viz:-

• ECOLOGY: biodiversity, habitat, community and ecosystem services maintenance

• ECONOMY: conservation of resources for food, fibre, water, energy, livelihood security

• ENERGY-EFFICIENCY: balancing energy inputs and energy outputs per hectare

• EMPLOYMENT: maintenance of links between creative jobs and place - ‘there to care’

• EQUITY: pursuit of justice in the production, processing and marketing of farm outputs

• ETHICS: enabling what is good, right and fair for genuine agricultural progress.

Farmers do not consider too arduous the required multi-disciplined rise in farm management

standards for integral management. Its adoption has visibly improved the farmed landscape, the

faces of participants and the integrity of relationships. Above all, as per CADeP’s objectives,

people have greater food security and more sustainable livelihoods than before its inception.

July 2009 299

Farm Management 17th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

9

References and further reading

Baingana, A., Tunstall, B. & Rich, S. (2005) – Sustainable Agriculture Poster Pack

www.fourthway.co.uk – Sponsors:- ACDI/VOCA, Agromisa, AHI, ASPS, Caritas, Farm Talk,

JIDDECO, NEMA, NOGAMU, SACU (Send-A-Cow Uganda) St Jude’s, Straight Talk Foundn.

Berry, R.J. – ed. (2007) When Enough is Enough. (Apollos, Nottingham, UK, 213 pp.)

Dorward, P., Shepherd, D. & Galpin, M. (2007) The development and role of novel farm

management methods for use by small-scale farmers in developing countries. In A Vibrant rural

economy: The challenge for balance, Vol.I Proceedings of the 16th World Congress of the

International Farm Management Association, Cork, Ireland. 348-358.

FAO (1989) Farming Systems Development. (FAO, Rome, 45 pp.).

Gwaivangmin, A.I.T. & Wibberley, E.J. (2004) Agrarian Advocacy in sub-Saharan Africa. (8

pp. In Advocacy, Proc. MICAH Network Consultation, Johannesburg, RSA, Sept.’04).

Joy, D.C. & Wibberley, E.J. (1979) A Tropical Agriculture Handbook.(Cassell,London 219 pp.)

Kinengyere-Mango, A. & Wibberley, E.J. (2006) Send-A-Cow Uganda Impact study of work

through Farmers’ Associations in Masaka & Iganga Districts. (Report, 34 pp.).

Kyamuwendo, E. (1999) The potential of the Farmer Dominant Study Group (FDSG) as a

practical strategic option for farmer to farmer training and extension of sustainable agriculture

with special reference to Uganda. MSc Thesis, Wye College, University of London, UK, 58pp.

Kyamuwendo, E. – ed. (2007) CADeP Budgets 2007 and 2008.

Kyamuwendo, E. – ed. (2008) CADeP Narrative & Financial Report 2006-2008 (July’08,19 pp).

Maathai, W. (2007) Unbowed. (Heinemann, London, 314 pp.).

Mortimore, M. & Manvell, A. (2006) Climate change: enhancing adaptive capacity. (NRSP

DfID, UK).

Mukalazi, K. (2008) Personal communication; i.c.Food & Nutrition Security, Church of Uganda.

Namutebi, A., Muyonga, J.H. and Tumuhimbise, A.G. (2007) Food & Nutrition in Uganda:

principles and community needs – especially Section V, pp.165-205 ‘Food handling, processing

and preservation’ (Makerere University/Fountain Publishers, Kampala, 222 pp.).

Press, S.A. (1980) Personal communication: South African Businessman of the Year Speech.

Turner, M.M. & Wibberley, E.J. (2009) Integral Management: Livestock, Landscapes &

Livelihoods in the SW English Uplands. Proceedings of IFMA 17th World Congress,

Bloomington, Illinois, USA.

Wibberley, E.J. (1997) Changes affecting Agricultural Extension in Uganda. Landmark 21, 4-5.

Wibberley, E.J. (1998) Equity implications of reforms in the financing and delivery of

agricultural extension services in Uganda: III - Feedback & Verification. (Report for AERDD

University of Reading/DFID, 28 pp.).

Wibberley, E.J. (2007) Vibrant Agricultural Management Messages from Africa. In A Vibrant

Rural Economy : the Challenge for Balance. Proc. International Farm Management Association

16th Congress, Cork, Ireland (Vol.III, 186-198).

Wibberley, E.J. (2008a) Farmer-Interactive Extension for Improved Management through

FARMS (Farm Asset Resource Management Study) Groups; an International Perspective. 12 pp.

In Global Entrepreneurship: the Role of International Agricultural and Extension Education.

AIAEE 24th Annual Conference, Earth University, Costa Rica (March 2008). www.aiaee.org

Wibberley, E.J. (2008b) CADeP (Congregational Agricultural Development Programme)

Uganda: Evaluation Report, 24pp. + appendices.

July 2009 300

Farm Management 18th International Farm Management Congress, Bloomington/Normal, Illinois, USA Peer Review Paper

10

TITLE OF PAPER

Integral Farm-Household Management for Food Security & Sustainable Livelihoods in

Uganda by Elijah Kyamuwendo(ı) and E. John Wibberley(²).

1

CEO of Kulika Trust, Uganda and Farmer in Mubende, Uganda.

2

Professor of Agriculture, Royal Agricultural College Cirencester, UK and team member of RURCON Africa.

THEME SECTION

Section 2. Farm Management, preferably, OR Section 5.Education & Training

PAPER FOR NON-PEER REVIEW (unless desired to be so)

WORD COUNT

Exactly 3,500 – including all tables/Figures but excluding abstract and references, of course.

AFFIRMATION

All this is our own original work, both in the field and in writing and has not been published

elsewhere.

Elijah Kyamuwendo farms with his family in Mubende, Uganda. After serving as Sustainable

Agriculture Co-ordinator of Kulika Charitable Trust, Uganda, he became its CEO. His MSc

thesis at Wye College, University of London covered adaptation to Uganda of FARMS Groups

(as developed between 1977 and 1992 by co-Author John Wibberley).

John Wibberley is a Professor of Agriculture & Resource Management consultant working in

the UK and internationally. Previously Head of Agriculture at the Royal Agricultural College,

Cirencester, England he serves within RURCON (a team of African Christian leaders engaged in

Rural Development in sub-Saharan Africa).

July 2009 301

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Guide To Climate Change and Food SecurityDocument28 pagesGuide To Climate Change and Food SecurityJoão SoaresNo ratings yet

- Zero-Waste Agriculture - Organic Berry FarmDocument58 pagesZero-Waste Agriculture - Organic Berry FarmGiaToula54No ratings yet

- Ecological Agriculture: Mitigating Climate Change, Providing Food Security & Self-Reliance For Rural Livelihoods in AfricaDocument16 pagesEcological Agriculture: Mitigating Climate Change, Providing Food Security & Self-Reliance For Rural Livelihoods in AfricaGiaToula54No ratings yet

- Pesticide ToxicityDocument238 pagesPesticide Toxicityqwer22No ratings yet

- Organic Agriculture and The Global Food SupplyDocument23 pagesOrganic Agriculture and The Global Food SupplyFriends of Tucson Cactus and Succulent SocietyNo ratings yet

- Organic Agriculture and Global WarmingDocument12 pagesOrganic Agriculture and Global WarmingGiaToula54No ratings yet

- Organic Agriculture and Food Security in AfricaDocument61 pagesOrganic Agriculture and Food Security in AfricaShogun Shakamouni HashiramaNo ratings yet

- Global Warming Impact On World FisheriesDocument42 pagesGlobal Warming Impact On World FisheriesGiaToula54No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Freee GeeeeDocument47 pagesFreee GeeeeRamon ColonNo ratings yet

- Dorper GrowthDocument22 pagesDorper GrowthHazel DalaguiadoNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Status, Husbandry Practices Followed and Constraints Faced by Madras Red Sheep Framers in Their Field Flocks of Kanchipuram DistrictDocument18 pagesSocio-Economic Status, Husbandry Practices Followed and Constraints Faced by Madras Red Sheep Framers in Their Field Flocks of Kanchipuram DistrictIndian Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences RNo ratings yet

- Effect of Feeding Concentrate Diets Containing Graded Levels of Groundnut Haulms On The Performance of Friesian X Bunaji Cattle PDFDocument224 pagesEffect of Feeding Concentrate Diets Containing Graded Levels of Groundnut Haulms On The Performance of Friesian X Bunaji Cattle PDFmekyno320% (1)

- Awakening Africa's Sleeping Giant? The Potentials and The PitfallsDocument7 pagesAwakening Africa's Sleeping Giant? The Potentials and The PitfallsBright SamuelNo ratings yet

- Bee Flora and Pollination of CropsDocument16 pagesBee Flora and Pollination of CropsSuryajeeva SuresNo ratings yet

- Module 1. Agriculture and Its Relevance: Learning OutcomeDocument4 pagesModule 1. Agriculture and Its Relevance: Learning OutcomeEuphoric FreakzNo ratings yet

- OnePlan Cattle Feedlot Planning GuideDocument18 pagesOnePlan Cattle Feedlot Planning GuideRakgadi LinahNo ratings yet

- Guide New Zealand Cattle FarmingDocument144 pagesGuide New Zealand Cattle Farmingjohn pierreNo ratings yet

- Bee AgskillDocument10 pagesBee Agskilleric38620% (1)

- 1944 Farra More Honey From BeesDocument6 pages1944 Farra More Honey From BeesMauricio NúñezNo ratings yet

- Simmons Prepared Foods, Inc. Is Recalling 2,071,397 Pounds of Poultry Products That May Be Contaminated With Metal.Document2 pagesSimmons Prepared Foods, Inc. Is Recalling 2,071,397 Pounds of Poultry Products That May Be Contaminated With Metal.FOX 28 NewsNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Improving Farmers Livelihoods - FAODocument53 pagesEvaluation of Improving Farmers Livelihoods - FAOtesfaye solomonNo ratings yet

- Tabuk City City Veterinary Office: Republic of The Philippines Province of KalingaDocument7 pagesTabuk City City Veterinary Office: Republic of The Philippines Province of KalingaLea Marie Caysoen-BulawitNo ratings yet

- All India Animal Feed ManufacturersDocument19 pagesAll India Animal Feed ManufacturersmanishNo ratings yet

- Mid-Term Examination in Animal Production 11Document5 pagesMid-Term Examination in Animal Production 11michael hobayanNo ratings yet

- Milk Production of Hand Milked Dairy Cattle in Burkina FasoDocument86 pagesMilk Production of Hand Milked Dairy Cattle in Burkina Fasofranky100% (1)

- Hirabe ReportDocument22 pagesHirabe ReportAbdi Fitah Muhudin HirabeNo ratings yet

- Essay On AgricultureDocument3 pagesEssay On AgricultureKen Khumancha100% (1)

- Andhra Pradesh Livestock Development Agency (APLDA) (To Be Updated in The Website WWW - Aponline.gov - In)Document17 pagesAndhra Pradesh Livestock Development Agency (APLDA) (To Be Updated in The Website WWW - Aponline.gov - In)gggNo ratings yet

- Dobling Rural Farmers IncomeDocument5 pagesDobling Rural Farmers IncomereinpolyNo ratings yet

- Milestone V OPDocument1 pageMilestone V OPAyen Rodriguez MagnayeNo ratings yet

- Black BeautyDocument5 pagesBlack BeautyOrlando CaizaNo ratings yet

- Pig Farming Book 3Document67 pagesPig Farming Book 3chavezallen199533% (3)

- 5 Year Development Plan Column1: Objective/S Activity/ProjectDocument2 pages5 Year Development Plan Column1: Objective/S Activity/ProjectDiane BangtuanNo ratings yet

- History Ch-5 QADocument3 pagesHistory Ch-5 QASudhanshu PadhiNo ratings yet

- The Lost Morgans of The Tehachapi MountainsDocument10 pagesThe Lost Morgans of The Tehachapi MountainsBrenda L TippinNo ratings yet

- Readtest2 PDFDocument21 pagesReadtest2 PDFManju GalagangodageNo ratings yet

- A Micro Lesson Plan For Week 1: Agricultural ScienceDocument2 pagesA Micro Lesson Plan For Week 1: Agricultural ScienceNwachukwu UchennaNo ratings yet

- Common Breeding Systems For Livestock ProductionDocument4 pagesCommon Breeding Systems For Livestock ProductionRica Mae EnvergaNo ratings yet