Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rice Is Essential But Tiresome, You Should Get Some Noodles' The Political-Economy

Uploaded by

Nelson DriftbreadOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rice Is Essential But Tiresome, You Should Get Some Noodles' The Political-Economy

Uploaded by

Nelson DriftbreadCopyright:

Available Formats

Rice is essential but tiresome, you should get some noodles: The political-economy of married womens HIV risk

in Ha Noi, Viet Nam

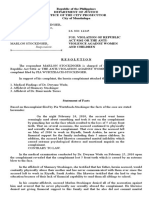

Harriet M. Phinney Department of Anthropology University of Washington Draft for American Journal of Public Health

This paper seeks to explain the rise of mens extramarital sex in Hanoi, Viet Nam and in so doing elucidate the manner in which married women are at risk of contracting HIV from their husbands.1 Rather than explaining the increase in mens extramarital sex by locating mens sexual desires in their bodies, a current trend in many behavioral studies of HIV risk in Vietnam, this paper denaturalizes male infidelity by examining contemporary male sexuality as a product of social, political and economic organization at a specific moment in time.2 The common assertion that Vietnamese men are and always have liked exotic and strange things (i.e. different women), forecloses understanding the unequal gendered processes and social structures through which sexual desires are elicited, organized and interpreted as social activity. 3(13) In urban Vietnam, contemporary sexualities are developing in new social spaces away from the home as a result of the intersection of local and global consumer economies. Recognizing that desire and sexual identities are social rather than individual phenomena enables us to shift our public health intervention strategies from focusing on individual behavior to

examining the social spaces where modern extramarital sexual identities are being performed. This paper focuses on the political and socio-economic conditions that structure mens opportunities for engaging in heterosexual extramarital sex, enabling it to occur and for certain types of extramarital relationships to become normalized. The paper begins with a discussion of the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in Vietnam, the Vietnamese governments response to the epidemic, and a brief account of research methods. I then describe mens extramarital sexual relationships and provide an account of mens attitudes toward condoms, their differential condom use, and the burden placed on women for reducing HIV transmission. Next, I depict a few of the changes Doi Moi [Economic Renovation instituted in 1986] has brought to Hanoi, in particular those that have most bearing on married womens HIV risk. The core of the paper explores the social factors that structure mens opportunities for engaging in extramarital sex. The overall significance of Doi Moi is that it has made space for the commodification of sexuality and the transformation of sexual geography in Hanoi, in turn putting married women at increased risk of HIV. Finally, based upon these findings, I propose three recommendations for policy and research in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS and the Vietnamese Governments Response The first case of HIV was reported in 1990 in Ho Chi Minh City. By 1991 HIV/AIDS had been reported in all 61 provinces throughout the country. In September, 2005 the Ministry of Health reported that Vietnam had 101,291 HIV/AIDS positive

people, of which 16,528 had developed AIDS, and 9,554 had died.4 The capital city of Hanoi had one of the highest prevalence rates in the country. The principal risk for HIV infection in Hanoi is officially defined as injecting drug use (IDU). The second most common risk factor is sexual transmission, mainly heterosexual. HIV prevalence among female sex workers (FSW) in Hanoi increased from 0.1% in 1996 to 14.5% in 2002.5 A behavioral surveillance survey, conducted in 2000 in Hanoi, indicates that drug use is common among FSW, with 29.3% of these ever having used drugs.6 A 2002 Behavioral Surveillance Survey conducted throughout the country suggests that sexual linkages between injecting drug user networks and commercial sex networks could result in the spread of HIV across and outside these core groups.7 Indeed, HIV/AIDS has spread beyond these high risk groups, and peasants, students, state employees, army personnel, and infants have been infected with HIV. A 2005 Ministry of Health report stated that Injecting drug use, sex work, and husband-to-wife transmission are fueling the Vietnamese epidemic. 8 The Vietnamese government first responded to the growing prevalence of HIV/AIDS in 1993 by issuing a series of directives that lacked an overall strategy for stemming HIV. In the early 1990s, the government also launched a Social Evils Prevention Campaign to stop people from engaging in harmful social practices such as drug use and prostitution. Because the HIV/AIDS epidemic emerged coincident with increased drug use and prostitution, the social evils legislation developed in tandem with HIV/AIDS legislation. As a result, social evils were linked to individuals with HIV/AIDS. This linkage has proved detrimental for preventing and controlling the spread of HIV/AIDS.9 The state is currently making a concerted effort to negate the association

between Social Evils and HIV/AIDS having recently recognized the deleterious affects of this linkage. In March, 2004, the Prime Minister approved the first national strategy, the National Strategy on HIV/AIDS prevention and control in Vietnam till 2010 with a view to 2020. The plan is designed to convey the vision, leadership, guidance, and measures for a collective national response to the epidemic. Unlike previous directives, the new one outlines specific steps, solutions, and programs for action and involves all the mobilization of government, party, and community level organizations at multiple sectors. The plan also broadens the definition of high risk individuals from injecting drug users and sex workers to include migrants and adolescents. The Vietnamese state and public health community, following the international community, recognize FSWs male clients to be a bridge population for HIV transmission from high risk behavior groups to the general population. Yet, the national HIV prevention program continues to focus the majority of its attention on FSW themselves, rather than their male clients. Sex workers are encouraged to take responsibility for making their clients use condoms, an often difficult job given the gendered and socio-economic inequality between them and their clients.10 Another strategy, not actually discussed in the national HIV/AIDS plan but implicit in the Womens Union tactics for creating Happy Families (part of the population program), places the burden for reducing HIV transmission on married women.11 The Womens Union encourages wives to satisfying their husbands sexually and be beautiful and alluring so that their husbands wont tire of them and seek out sex outside marriage. The strategy of focusing on women to reduce HIV transmission is

problematic because, as Katherine Frank points out, focusing public efforts on the social transgressions of women results in a process that normalizes the desires that motivates their customers.12(2) Indeed, while society holds women responsible for limiting the spread of HIV/AIDS, men encounter opportunities just about everywhere they go, in and out side Hanoi, for engaging in extramarital sex.

Research Methodology The data for this study come from ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Ha Noi, Viet Nam from February through July, 2004. The research was carried out by the author in collaboration with Nguyen Huu Minh, the Vice-Director of the Institute of Sociology (IOS) at the Vietnamese Academy of Social Sciences (VASS) in Ha Noi. The ethnographic fieldwork consisted of 4 components: marital case studies, key informant interviews, participant observation, and archival data collection. All researchers conducted fieldwork in the Vietnamese language and all research participants were of the majority Kinh ethnic group. The Kinh is the most economically and politically dominant, ethnic group in Viet Nam, as well as the most demographically significant. Their marriage traditions follow a neo-Confucian influenced doctrine that prior to the socialist era permitted polygyny. Marital Case studies Two male researchers and three female researchers from IOS were hired to conduct 22 marital case studies (11 wives and 11 husbands); the men interviewed the husbands and the women interviewed the wives in separate locations at different times.13 The studies provide accounts of the different ways husbands and wives at different stages

of marriage discuss, perceive, and describe the same marriage. Through the studies we learned about how marital relationships began, how they developed over time, what couples communicated about, the role of sex in the marriage, how the division of familial labor was gendered, and how couples spent their leisure time, and if the spouse had engaged in extramarital sex.14

Insert Table 1 here

Key Informants The author interviewed 14 key informants after most of the marital case studies had been completed in order to follow up on topics that had emerged from the marital case studies, issues on which we wanted clarification or socio-historical context. A researcher from IOS was hired to transcribe all recorded interviews.

Insert Table 2a and 2b here

Participant Observation The author conducted participant observation throughout the six months of the fieldwork. Participant observation enabled the researcher to view men and womens multiple self presentations of themselves at different times and different places. This proved particularly valuable for understanding the way in which the organization of various spaces facilitate or hamper sexual activity and they way in which individuals act differently in different spaces.

Insert Table 3 here

Archival Data Collection A researcher was hired to collect collected newspaper articles, magazines and music for a two year period each decade, beginning in 1970 and 1971. This time frame enabled us to compare discussions related to marriage, sex, and love over 4 different time periods representing different socio-political and economic periods in contemporary Viet Nam.

Mens Extramarital Sex and Condom Use Seven of the completed 22 men with whom we conducted marital case studies admitted to having had or currently were having extra-marital sex. (We also conducted in-depth interviews with four other married men; two of whom had extra-marital relations). All 22 men had some friends or acquaintances who were having extra-marital relations, either casual unplanned sex with sex workers or regular sex with girlfriends. Public health professionals in Hanoi debate whether the reported figure of 40% of married men ever having extra-marital sex is high enough.15 Mens extra-marital relationships can be broken down into two categories, short encounters with sex workers or longer term love relationships. Our data, in conjunction with other research, indicate that a wide range of men of all ages (young, middle aged and elderly) from students, to uniformed service workers, police, construction workers,

men working in the transportation industry, and government workers buy services from female sex workers.16 Long term extramarital love relationships between men and women working in the same office have become much more common over the past decade, in part due to the increase in white collar employment. The couples communicate with each other by cell phones and arrange to meet for lunch or after work in another part of town. It has become fashionable to meet one another for lunch and then slip into a nha nghi [rest house] or caf om [hugging caf] for a little after lunch fun. Relationships between office colleagues often began as friendships and developed into something more serious that involves sex. These relationships tend to be hidden because love relationships threaten to shatter family happiness causing the destruction of a mans or womans marriage. As a result they are not considered socially acceptable. In contrast, if a married man has sex with a sex worker (and is careful not to bring home any diseases) he is considered to be behaving in a perfectly understandable manner. All of our informants provided rational explanations for married mens desire to visit sex workers and found the mens behavior acceptable, albeit unfortunate. They did not condemn the men for needing to satisfy their sexual desires. Relationships between a man and his female secretary are increasingly common. Though these relationships are problematic due to the gendered disparity in power, both the men and their secretaries benefit from the relationship. The men have pretty, young women to accompany them when they go away from home for business and the secretaries are able to enjoy some of the comforts of life otherwise not available. In addition, both are able to engage in a type of intimacy, sexual and affective, not available

to them in other social contexts. In contrast to the love relationships among colleagues of equal socio-economic standing, boss/secretary relationships are more public, principally because they are part of mens efforts to gain prestige from other men. If men used condoms with these extramarital partners, then would be no inherent relationship between these patterns of extramarital sex and married womens HIV risk. However, they rarely do use condoms. It was quite common for men to say that they always use condoms with sex workers. Yet, behavioral studies of sex workers and their clients in Hanoi indicate that condom use is low.17 One of our informants said that there was no need to use a condom with high class sex workers because they were clean, implying that they were disease free. None of the men felt it was necessary to use a condom with his girlfriend or his wife. Should he do so, both women would be suspicious that he is having sex with someone else. The risk of HIV transmission is most evident in the behavior of one of our informants who insisted on kicking barefoot. He does not use condoms with his lover, his wife, or the sex worker. The tendency of wives to avoid conflict with their husbands, remain silent about their suspicions of their husbands infidelity, or accept his infidelity after complaining and trying to get him to stop, contributes to womens risk of contracting HIV from their husbands.18 Married womens dependence on the social status and economic security provided by their husband prompts them to keep silent and remain married rather than seek divorce.19 As Robin Sherrif has pointed out, silence is not necessarily an individual choice, but a shared silence that is socially organized, expected, and recognized.20 This socially accepted silence contributes to married womens risk of contracting HIV from their husbands.

The unfortunate irony is that Vietnamese men (and women) are exploring new modern sexual selves at the same time that HIV/AIDS is moving from a concentrated epidemic to one that is spreading into the general population. Married men are the most likely route through which this will take place. Their wives, who would otherwise be at low risk of HIV/AIDS, are now at increased risk of contracting HIV from none other than their own husbands.

Doi Moi [Renovation] and the normalization of Mens extramarital sex It is widely asserted among social science researchers, Vietnamese government officials, and non-governmental agencies that the spread of HIV/AIDS is correlated with Doi Moi [Renovation].21 Yet, exactly how the political economic changes accompanying Doi Moi have contributed to the spread of HIV/AIDS, however, has not been explicated. Our fieldwork generates data on how increasing gendered inequalities, socio-economic and cultural change, which are part of Doi Moi, combine to transform old sexual desires and create new ones essentially, to produce a situation in which some married mens extramarital relations are no longer considered aberrant or entirely socially unacceptable.22 In 1986, the Vietnamese government first, cautiously, then, fundamentally, transformed the Vietnamese economy from a centrally planned economy to a market economy with a socialist direction. In addition to dismantling its agricultural based cooperatives in favor of household production, the state removed most welfare subsidies,23 closed and downsized state factories in favor of promoting private enterprise, enabled the expansion of export markets, and loosened restrictions on domestic and

10

foreign migration. Doi Moi policies have had the most impact on urban areas and their surroundings.24 Changes that have had particularly notable influence on reshaping sexuality are the emergence of social stratification; increased gender inequalities; the commercialization of womens bodies; rapid urbanization;25 affordability of motorized vehicles; availability of cell phones; and access to the internet, porn, foreign films, literature and news26 all of which provide alternative images of marriage, love, romance and sexual relations images previously inaccessible to most Vietnamese.27 The recent increase in gender inequalities has direct bearing on the rise of mens extramarital sex and risks to married womens risk of HIV infection.28 Although more women have access to economic opportunity and are in political office than before Doi Moi, there has been a significant increase in gender disparities.29 Many young women from rural areas have left their homes to seek employment in the sex industry. The states passive accommodation to the commercialization of womens bodies has led to a dramatic increase in the number of sex workers in Vietnam.30 This has been accompanied by the sexualization and commercialization of mens leisure and changing norms and attitudes toward sexuality and sexual relations.31 While men and women did participate in extramarital sex prior to Doi Moi, it is with Doi Moi that a series of social, cultural and economic changes have intertwined to create a set of opportunity structures that promote mens access to extramarital sex in specific ways. By opportunity structures I mean the political and socio-economic conditions that enable a behavior to occur and become common or normalized. The extramarital opportunity structures that have contributed to the rise in mens extramarital sex as part of the process of Doi Moi, and that in turn have increased married womens risk of HIV include, the ideology and structure of marriage,

11

the commodification of sexuality, the emergence of modern masculinities and transformed male prestige structures, and new forms of geographic mobility and labor migration. Together these have made extramarital sex a widespread urban phenomenon that must be understood as a product of changing social organization and political economy.

Gendered Ideology and Structure of Marriage Marriage is an institution in which personal desires, familial concerns, and state agendas converge to normalize specific subjectivities, identities and sexualities.32 Marriage in Vietnam, influenced by Confucian doctrine, is organized along patrilineal and patrilocal principles. Since the 1940s, Vietnamese intellectuals, nationalists, and political leaders at different times have sought to re-define marital ideology and to structure the marital relationship to fit their respective agendas. The most significant change was implementation of the 1959 Law on Marriage and the Family which outlawed polygamy and promoted monogamous marriages based on voluntary love. More recently, with the advent of Doi Moi, the Vietnamese state promoted a new vision for the modern nuclear family, one that is happy, healthy and wealthy. As Vietnam becomes increasingly embedded in the global economy, marriages evolve in a socioeconomic context of increasing gender inequalities, shifting sexual ideologies, and modern consumer desires. Despite neo-Confucian and socialist doctrines to the contrary, in early 21st century Hanoi, marriage itself facilitates mens opportunities to engage in extramarital sex due to five factors.

12

First, our data show that marriage is a project in which the marital union, what it represents, and the socio-economic status it provides is larger than and supersedes individual (husbands and wives) and immediate concerns. The creation and maintenance of economic stability, upkeep of the house, the upbringing of children, and the care for extended family members, occupies most married couples conversations. Though love and sexuality are considered important for a good marriage, ultimately it is the goal of having a stable and happy family that keeps couples together. Thus, for example, should a wife find out that her husband has had an extra marital relationship, she will likely try to put her anger behind her for the benefit for her children and the marriage, though she will, as men joke, be jealous as a red hot chili pepper. Women swallow their anger at infidelity because they derive their primary social status from their roles as wives and mothers, not from their high ranking office positions.33 Second, choice of spouse has bearing on whether a husband may seek an extramarital relationship. A man might not choose for a wife the kind of woman that he desires for a girlfriend. A man may love a woman very deeply. She may be an independent, modern, dynamic woman, but when he takes a wife he takes someone who follows tradition someone who speaks quietly, bears difficulties easily, and can take care of children, said one key informant.34 Despite the vastly different socio-economic historical contexts in which our informants of different generations chose their spouse, they all were concerned with choosing a wife who would provide an economically stable, happy, and harmonious home conducive to raising children. Thus, many men joked that as the title of this paper implies, your wife is your rice [com], but it is bland and gets tiresome, so you should go out for some noodles [pho]. Pho is sweet and delicious. Like

13

mens opportunities for new kinds of sexual experiences, Pho has become increasingly sought after and available outside the home since the early-mid 1990s when this joke began to circulate. At the same time, men who were having extramarital sex with sex workers stated that they loved their wives very much. None of them ever had any intention of leaving their wives and did not feel that that engaging in sex outside of marriage endangered family happiness. Taking a lover, on the other hand, did pose a potential threat to family happiness and therefore was looked down on by most informants.35 Third, because womens household labor is structured around domestic chores, women have less leisure time than their husbands. When they do have free time, it is organized around family activities. The husbands role, as pillar of the family, is to have a good understanding of society. This role encourages and enables men to explore the changing urban environment and to socialize with male friends in new gendered social spaces, many of which provide pretty girls. Thus, the gendered division of household labor promotes male homosociality, presenting men with opportunities to engage in nonmarital relationships. The fourth aspect of marriage which has implications for mens extramarital sex is marital sex.36 These include gendered notions of sexuality, the circumstances of married sex, and reproducing and aging bodies. Though gendered notions of sexuality are in flux, a number of factors inform the way our informants thought about their sexual relationship with their spouse. Although all of our informants felt that sexual compatibility is essential for a happy marriage, most felt that sex was something men did for fun, whereas women had sex for reproductive purposes, a belief rooted in neo-

14

Confucian philosophy which states that a womans first duty to her husband was to provide him with a son in order to pass down his lineage. All informants stated that men are responsible for initiating sex and it was inappropriate for women to do so. As a result, women are typically construed as being passive to male sexual desire and not wanting to have sex as frequently as men.37 These beliefs have been reinforced by a lack of understanding of sexuality38 and the belief that sex is not something polite to talk about.39 Only the younger couples admitted to having sex for fun. Indeed, most of the women from the older generation never found sexual intercourse pleasurable, and only had sex when their husbands wanted it. Though all of the husbands denied forcing their spouse to have sex, all of the wives responded that they did have sex at one time or another simply to fulfill their wifely obligations.40 In the end, all of the wives were at some level sexually submissive to their husbands sexual desires. 41 All of our respondents felt that it was understandable for a man to engage in extramarital sex if he and his wife were not sexually compatible.42 Our respondents also said that men often seek out extramarital sex because their wives are too weak to have sexual intercourse or that she can not satisfy his sexual needs.43 Men who engaged in extramarital relations for such reasons received far more social acceptance than wives who did so for the same reason. Fifth, the circumstances under which couples have sexual intercourse have direct bearing on a couples sexual relationship. Circumstances vary depending on how many family members share a living space, whether or not a couple has their own room or just their own bed, whether they live separately from extended family, and if they have a young child in the house.44 Some of the older husbands and wives talked about what it

15

was like having sex their first night of marriage, sleeping on a bed in a room in which a thin piece of cloth was hung to give the newlywed couple privacy. One woman in her 50s said she had never had sex with her clothes off and always had it in the dark. Other women talked about the pain of sexual intercourse due to lack of foreplay or limited foreplay. Many women reported abstaining from sex while they were pregnant and for 3 months after the child was born. Many men felt this was an acceptable time for husbands to seek sex outside marriage. Finally, when husbands and wives bodies age, they may no longer be able to perform sexually as they once did leading their spouse to seek sex elsewhere.

Commodification of Sexuality The second opportunity structure for mens extramarital sex associated with Doi Moi is the commodification of sexuality. Integration into the global market economy and economic growth has made possible and encouraged the commercialization of leisure space and the commodification of leisure itself45 - and, in turn, the sexualization of mens leisure. In the early phase of Doi Moi, male entrepreneurs from state and privately owned businesses began the custom of treating one another to a good time with food, drink, and commercial sexual services.46 The purpose of these business meetings was to establish personal ties that would facilitate economic transactions. In the process, the state became silently complicit in the growth of the sex industry, an industry which

16

developed out of the commercialization of state businesses at a time when the state was venturing into the global market economy. Offering food, drink and women remains obligatory in many business practices today and has spurned a whole new set of enterprises geared to providing sexual services for men.47 The commodification of womens bodies has become part of the new commodification of male leisure, itself an example of social transformations taking place in Vietnam as result of the changing political economy.48 A former manager of a minihotel told me, We provided male guests the service of finding pretty girls for so the men would not be lonely while they were away from their families. A lot of mini-hotels were built in the mid to late 1990s. Providing women enabled us to remain economically competitive.49 The changing urban landscape now includes a dizzying array of spaces where men can go for sexualized encounters with women,50 to purchase sex or where lovers can go to be on their own: nha nghi [rest houses],51 karaoke,52 bath cafes, hairdressers, barbers, night clubs, garden cafes, cafes,53 massage parlors, fishing huts, bus stations, dancing halls, train stations, and of course the street. 54 As one Hanoi resident remarked, Even if you dont have sex needs they try to excite you to push you so that you feel like you want sex. The sex industry thus offers men a variety of places and scenarios that provide men from a range of professions with different needs, incomes, time tables, work schedules, and marital situations numerous kinds of opportunities to engage in extramarital relationships.55 Despite the illegality of prostitution in Vietnam, the gendered inequalities and social stratification that have increased gender disparities in

17

favor of men that have arisen during Doi Moi lead many young girls to commercial sex, further increasing mens access to extramarital sex.

Modern Masculinities and Male Prestige Structures A third opportunity structure conducive to mens extramarital affairs is modern masculinities and male prestige structures. Contrary to assumptions underlying a number of epidemiological studies on the male clients of sex workers, Vietnamese masculinity is not inherent in a mans body and thus fixed. Rather, gender is produced through social practice through acts, gestures, desires, and discourses.56 Throughout different periods of Vietnamese history, Vietnamese men have produced, practiced, and identified with variety of masculinities.57 Among certain sectors of society in Hanoi today, urban masculinities are becoming increasingly linked to sexual experiences, largely the result of the commercialization and sexualization of mens leisure activities discussed above. Although a lot of men keep their extramarital affairs private, an increasing number of men engage in sexualized leisure activities as part of male homosociality. As mens leisure has become increasingly commodified, mens consumption has become a means for differentiating themselves from other men, for demonstrating their social mobility and social class.58 In 2004/2005, mens ability to pay for food, drink, and women enabled them to perform a masculinity which was not socially condoned or available to their parents. Men boasted in the office about their sexual exploits the night before and white collar bosses were proud they had managed to snag a pretty secretary to accompany them on business trips -since their wives have to stay home with the children.

18

Middle aged men, in particular, due to their monetary or political power, had many more opportunities to take advantage of the services the sex industry offers. It is important to note that male prestige is both aggressively and passively acquired. Some men certainly go out looking for sex. Many men, however, do not intend to find a girl every time they go out drinking with the men or with business acquaintances. In fact, if they do end up with a girl, they portray themselves in a passive light. As one man said, If a pretty girl sits on my lap and I refuse her she will ask me if I am crazy or if I lost my penis or whether it doesnt work anymore. Many of our respondents spoke of how the intense pressures society placed on men to participate in sexualized practices available to them in the new market economy.

Male Mobility and Labor Migration Fourth, new forms of geographic mobility and labor migration provide men with constant access to extramarital sex.59 According to our findings, professions that provide men the most opportunities for extramarital relations are white collar jobs (state and private enterprises), the entertainment industry, the hotel industry, and the transportation industry. In fact, of the seven men in our marital case studies who had ever had extramarital relationships, four of them earned their livelihood in the transportation business. This corroborates the commonly held thought that men who work in the transportation industry have lots of extramarital sex. Truckers, taxi drivers, drivers who work independently, drivers employed by a private business or state enterprise, xe om [hugging taxis - motorcycle taxis], and men who drive for tourist companies have many opportunities to engage in extramarital relationship.

19

One of our informants who drove for a private company talked about how his boss always asked him to join the business meetings. Bowing to social pressure, he said he typically feigned interest by going off to another room with a young woman. Instead of having sex, he paid her to tell him about her life and how she ended up working as a prostitute. He added that, most men on such occasions do take advantage of the situation, either meeting the girls later or taking them back to their hotel. Another married informant who transported goods long distances developed a relationship with a woman in another city whom he visited regularly when traveling. What all of the men in these various professions have in common is the ability to be mobile in a way and to an extent that their wives were not. It is their mobility that provides them the opportunity to have access to access to women other than their wives. The leisure and sex industries, in turn, provide these men with the venues and the women.

Conclusion Married womens risk of HIV infection in Vietnam derives from a combination of factors, including changing marital ideology, gendered socio-economic inequalities and asymmetries structuring married couples lives, the commodification of sexuality, and increase in male leisure time and mobility. This research, by demonstrating the extent to which mens extramarital relationships are an integral part of contemporary social organization, rather than random sexual acts engaged in as a result of mens inherent nature, points to possible arenas for public health intervention.60 First, the complicity of the Vietnamese states passive accommodation to mens extramarital sex needs to be addressed. The state and NGOs need publicly to recognize and acknowledge that the

20

ongoing practice of providing sexualized services to business associates contributes to the normalization of mens extramarital sex at the same time it provides a venue for HIV transmission. These business practices conducted among men working in state and private businesses may, in the long run, put the socio-economic progress of the country at risk due to the fact that many of these business men are some of the more educated and powerful members of society. Second, public health interventions should target men in the commercial social spaces where they engage in risky behavior. Family Health International, a private foreign non-governmental organization has begun to conduct this type of health intervention.61 Their efforts should be expanded on a nation-wide scale. Places of employment, often the locus of sexualized male business deals, could promote sexual health among their employees. One of our informants said that he did not participate in the sexual services offered to him as part of a business deal specifically because his place of employment did not condone or permit it. He took their admonitions seriously. As of yet, this is an unexplored venue for public health intervention. Third, the state should call upon men to take responsibility for protecting their country, their wives and their families from HIV. Public health programs need to shift their focus from sex workers to the men who are paying for their services. To date, men are all but missing from the new national HIV/AIDS plan. This is unacceptable. Our data indicates that many men, despite having a fairly good understanding of HIV risk and transmission, do not believe that their unprotected extramarital sex puts them at risk of contracting HIV (especially those who have sex with their lovers). Health education programs need to target men separately and directly.

21

Ethnographic and epidemiological research that has been conducted around the world indicates that a womans greatest risk for contracting HIV is from being married. The research suggests that married women risk being infected with HIV by having sex with their husbands. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), United National Population Fund (UNFPA), and United National Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the Crisis. (New York and Geneva: UNAIDS/UNFPA/UNIFEM, 2004). United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), Economic and Social Progress in Jeopardy: HIV/AIDS in the Asian and Pacific Region, ST/ESCAP/2251. (New York: UNESCAP, 2003). 2 Jeffrey Weeks, Jeffrey, Sexuality (London: Routledge, 2003). Richard G. Parker and John H. Gagnon, 1995. Conceiving Sexuality in Approaches to Sex Research in a Postmodern World (Routledge: New York, 1995): 13. 3 John H. Gagnon and Richard G. Parker, Conceiving Sexuality. In: Richard G. Parker and John H. Gangon, eds. Conceiving Sexuality (New York: Routledge, 1995). 4 Ministry of Health/Family Health International. 2005. HIV/AIDS Estimates and Projections 2005-2010. http://www.unaids.org.vn/resource/topic/epidemiology/e%20&%20p_english_final.pdf 5 Trung Nam Tran, Roger Detels, Hoang Thuy Long, Hoang Phuong Lan, Drug use among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam, Society for the Study of Addiction (2005): 619-625. 6 The Ministry of Labour, War Invalids and Social Affairs states that among the 36,800 known sex workers in Viet Nam, 34.6 percent of them are drug users, and 18.4 percent of the drug users are HIV positive. Nguyen Minh Thang, Vu Thu Hong and Marie-Eve Blanc. 2002 Sexual Behavior Related to HIV/AIDS: Commercial Sex and Condom Use in Hanoi, Viet Nam, Asia-Pacific Population Journal (17): 41-52. 7 P.M. Gorbach, Vu Thu Huong, and Maria-Eve Blanc, Sexual Behavior Related to HIV/AIDS: Commercial Sex and Condom Use in Hanoi, Vietnam. Asia-Pacific Population Journal (2002): 41-52. 8 Ministry of Health/Family Health International. 2005. HIV/AIDS Estimates and Projections 2005-2010. http://www.unaids.org.vn/resource/topic/epidemiology/e%20&%20p_english_final.pdf 9 Due to severe stigma associated with drug use and sex work, intravenous drug users and female sex workers went underground to avoid being sent to re-education centers or treatment centers where they were poorly treated and often humiliated. A number of discriminatory practices were implemented in order to control the spread of HIV infection. In 1999 HIV positive individuals were banned from working in some professions. Testing for intravenous drug users, female sex workers, blood donors, and prisoners was made mandatory. HIV positive drug users and sex workers were often detained for rehabilitation. The detention policy, mandatory testing, and the lack of anonymous testing services deterred individuals from wanting to participate in health outreach programs. In addition, HIV positive individuals and their families have been stigmatized and discriminated against due to many peoples ignorance and fear of the disease and its association with sex and death. This has prompted many young women who contracted HIV from their husbands to leave their communities and move to a location where no one knows them. 10 I do not want to imply that sex workers have no agency and no control. They do, yet it is circumscribed by their personal and socio-economic situations which led them to sex work in the first place. 11 For an in depth discussion on these Womens Union tactics see Thu-Huong Nguyen-Vo, Governing the Social: Prostitution and Liberal Governance in Vietnam during Marketization (UMI Dissertations, 1998). 12 Katherine Frank, G-Strings and sympathy: Strip club regulars and male desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998): 2. 13 The author made the decision to hire Vietnamese researchers to conduct the formal marital case studies for the following reasons. 1) As a foreign research, the author would have had been accompanied by a member of the Hanoi Womens Union (WU), or a member of the city districts Peoples Committee (PC), or by another researcher. Given the private nature of the interview, I felt we would achieve better results if one person conducted the formal martial case studies than two. 2) If the author conducted the marital case studies and we followed the protocol initially formulated, we would have been introduced to our informants through the WU or the PC of each city district. This would have determined the types of marriages we would learn about give the WU and PCs penchant for representing their districts in the best light. Instead, the Vietnamese researchers worked on their own, undertaking the snowball to finding informants. As a result, they were able to locate individuals on their own without interference.

22

14

All respondents agreed to participate after first being presented with protocols for informed consent approved by institutional review boards in both the U.S. and Viet Nam. The interviews were taped, transcribed and coded. 15 This study focused primarily on mens heterosexual sex. However, our research in addition to other research suggests that gay men are becoming more outspoken and visible in their demonstration of their sexual preferences. Given that many men who have sex with other men are married and keep their homosexual behavior a secret due to social stigmatization, combined with their increased risk of HIV infection, they may well be placing their wives at risk of HIV. See: Donn Colby, Nghia Huu Cao, Serge Doussantousse, Men Who have Sex with Men and HIV in Vietnam: A Review. AIDS Education and Prevention 16(2004): 45-54. 16 Nguyen Minh Thang et al. 2002 Sexual Behavior Related to HIV/AIDS 17 Nguyen Minh Thang et. als survey of university students, factory workers, government officials, business men and service providers (including hotel and restaurant workers), and mobile workers (drivers and other mobile laborers) in Hanoi in indicates that A number of men think that having sex with expensive prostitutes, young girls and girls who live in remote areas is safe and therefore do not use condoms with those women (Ibid., 51). Only 36.4 percent of those surveyed always used condoms. Another study, a small qualitative study of drug use, sexual behaviors and practices among female sex workers in Hanoi indicates that the client makes the final decision regarding whether or not to use a condom and sex workers will frequently agree to not using a condom if they are offered more money. Trung Nam Tran, et al., Drug use, sexual behaviors and practices among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam a qualitative study International Journal of Drug Policy 15(2004):189-195. Trung Nam Tran et al.s study also suggests that there is a tight relatedness between the female sex workers and the intravenous networks in Hanoi because The main sources of infection among FSWs appear to be sharing of needles and syringes with other IDUs and having unprotected sex with their drug-using partners. Nor do the FSW use condoms with their regular clients and the FSWs clients range from blue-collar to whitecollar workers. The FSW are probably the major bridge of HIV transmission from the high-risk groups to the general population (ibid), 193). This is of significant concern given that the HIV prevalence among FSW has been steadily increasing and there appears to be no slow down of men seeking commercial sex Trung Nam Tran, et al., Drug use among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam. 18 An example provided by one of our marital case study informants described the situation of a wife who confronted her husband about his hanging out with women at his workplace. He responded that because he was the manager of a karaoke bar, it was part of his job to get to know the women and that she just had to put up with it. She does and now remains silent. For a discussion regarding Vietnamese womens silence with regard to sexual coercion in marriage see Phan Thi Thu Hien, Sexual Coercion within Marriage: A Qualitative Study in a rural area of Quanh Tri, Vietnam, Masters Thesis (The Netherlands. University of Amsterdam: Faculty of Social Science and Behavior. 19 Clearly not all women remain silent. Divorce is on the increase. Domestic violence and allegations of infidelity and incompatibility have become most common reasons for divorce. Yet this increase needs to be placed in a larger socio-historical context recognizing that prior to Doi Moi, the state limited the number divorces it granted each year. As implied above, divorce is most common among well educated white collar women who do not need to rely on their husbands income. In addition, whether a woman is in a social and economic position to live separately from her husband is an important factor in her decision to divorce. 20 Robin Sherrif, Exposing Silence as Cultural Censorship: A Brazilian Case American Anthropologist 102(1): 114-132. 21 From its founding in 1954, the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam tried various methods to rein in extramarital sexuality. In 1959 the government revised the Law on Marriage and the Family to promote marriage based on free will, mutual respect, and love. Prostitution and polygamy already having been outlawed, monogamy could become the locus for satisfying mens sexual and reproductive needs. During and after the Indochina wars the Party enacted punitive measures for party members who transgressed socialist marital ideals. In the mid 1990s the government launched a Social Evils Prevention Campaign to eradicate deviant behaviors by restricting non-Vietnamese cultural images and by condemning behaviors such as drug use, pornography and prostitution. At the same time, at different historical moments, the state has acknowledged the need for some men to engage in extra-marital sex (e.g. to help older single women who asked for a child or to establish second marriages (Harriet Phinney, Asking for a child: The refashioning of reproductive space in post-war northern Vietnam, The Asia Pacific Journal of

23

Anthropology 16(2003): 215-230. In the new Doi Moi era, the states acceptance or as others may put it its inability to control - mens extra-marital sexuality takes on new meaning in an expanding market economy marked by an increase in a gendered social stratification and other forms of inequality. 22 As stated above, extramarital relationships that destroy a married mans familys happiness are not considered acceptable. 23 This has resulted in the eradication of social nets including, health and child care, care for the infirm and reductions in educational support. See David Craig, Familiar Medicine: Everyday Health Knowledge and Practice in Todays Vietnam (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002). 24 Hanoi has become a much more diversified and open society. Describing the change, one Hanoi native said, It used to be a small town; we knew everyone and everyone knew what we were doing. Now you dont even the person living next to you, the social connections between people are looser. As a result, you can pretty much do anything you want and no one will know (Interview with male respondent, July 2004). 25 In contrast to the pre-Doi Moi era when migration was limited by the state, there is now an increasingly mobile work force, both seasonal and long term. Large numbers of migrants seeking economic opportunity have been moving to the cities, dramatically changing the urban landscape and the social dynamics of city life. The majority of these migrants are from neighboring provinces. Seventy five percent of the migrants are between the ages of 13-19, and forty eight percent are between the ages of 24-33. Men migrate in slightly larger numbers than women. Michael DiGregorio, A. Terry Rambo, and Masayuki Yanagisawa, Clean, Green, and Beautiful: Environment and Development under the Renovation Economy in Postwar Vietnam: Dynamics of a Transforming Society, ed. Hy V. Luong. (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003): 171-200. Hanoi currently has a population of 2.5 million plus additional immigrants (300,000) from other provinces. As the population of Hanoi has grown so has its urban land area. In 1960, the land area was 58 square kilometers and by 1998 it had grown to 91 square kilometers and is expected to grow to 121 square kilometers by 2010 (Ibid: 190). For further discussion on urban changes see: Mike Douglas, Michael DiGregorio, Valuncha Pichaya, Pornpan Boonchuen, Made Brunner, Wiwik Bunjamin, Dan Foster, Scott Handler, Rizky Komalasari, Kana Taniguchi, The Urban Transition in Vietnam (Vietnam: United Nations Development Programme, 2002). 26 David Marr, A Passion for Modernity: Intellectuals and the Media in Post-war Vietnam: Dynamics of a transforming Society, ed. Hy V, Luong (Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2003): 257297; Khuat Thi Hai Oanh, How do Vietnamese Youth Learn About Sexuality in the Family? (Hanoi: Institute for Social Development Studies, 2004). 27 Even the Peoples Army production of the new movie Bar Girl, a propaganda movie designed to frighten people away from the social evils of prostitution and drug use, is designed to titillate its audience by showing girls in bikinis and Vietnams first ever breast shot uses sex to draw in its audience. Mona Mangat Sex and Drugs Sell Eastern Horizons 14(2003). http://www.unaids.org.vn/event/sexndrugs.htm 28 Research on the impact of Doi Moi on gender equality suggests that, in general, women have not fared as well as men. However, it is dangerous to generalize about all Vietnamese women; whether or not a woman benefits from Doi Moi will be depend on her class, geographical residence, and the manner in which she intersects with the market economy. See, Gisele Bousquet and Nora Taylor, Le Viet Nam au Feminin [Viet Nam: Womens Realities] (les Indes Savants: Paris, 2005) and Jayne Werner and Daniele Belanger, Gender, Household, State: Doi Moi in Viet Nam (Cornell University Southeast Asia Program Publications: Ithaca, 2002). 29 A gender gap has emerged in literacy rates with mens literacy twice that of women, school drop-out rates are higher among girls than boys; women loose out to men in high income occupational opportunities. 30 See, Ha Vu, The Harmony of family and the silence of women: Sexual behavior among married women in two northern rural areas in Vietnam (Columbia University of New York Research Track- SMS: New York, 2002). For an examination of the way in which changing mode of governing contributed to the increase in the sex industry, see Thu-Huong Nguyen-Vo Governing the Social. 31 See Dang Nguyen Anh and Le Bach Duong, Issues of Sexuality and Gender in Vietnam: Myths and realities of penile implants and sexual stimulants (Institute of Sociology: Hanoi, n.d.) and Le Bach Duong, Sexuality Research in Vietnam: A review of the literature (Ford Foundation: Hanoi, 2001). See also Khuat Thu Hong. 1998. Study on Sexuality in Vietnam: the known and the unknown issue (Population Council: Regional Working Papers, No. 11, 1998) for an assessment of changes in sexual behavior from the pre-Doi Moi Era; Thu-huong Nguyen-Vo, ibid.

24

32

Sara L. Friedman, The intimacy of state power: Marriage, liberation, and socialist subjects in southeastern China American Ethnologist (32(2005): 312-327. 33 Womens abilities to swallow their anger are rooted in long term cultural values and more recent social changes. First, the Vietnamese state and family has long asked and expected Vietnamese women to sacrifice their personal desires for other. Second, The Womens Union has been promoting a female identity routed in womens maternal body since Doi Moi to the exclusion of other possible subjectivities such as those promoted in the past or those available as a result of the new market economy. Third, for many married women, particularly those in the middle and elder age groups whose husbands work out of the home, their most significant relationships are not necessarily with their husbands, but with their children, especially their sons, or their mothers-in law. Fourth, friendships with office mates or co-workers are increasingly taking on more importance in peoples lives. Before, the family was everything, said one female key informant. As a result, the husband-wife relationship is organized more around project of maintaining a happy nuclear and extended family than around the affective relationship of the conjugal couple. This is the case for younger couples as well despite their obvious interest and efforts to attend to one anothers sexual and emotional needs. 34 If, on the other hand, a man does marry a woman who presents a sexy public self, he will want her to wear different clothes in public once she gets married; he doesnt want other men looking at her. 35 Having sex with a sex worker, on the other hand, is not considered risky because men are believed to be capable of having sex without loving someone. There are two exceptions. Older couples whose children are grown may take a lover if their spouse no longer can perform sexually. One of our informants felt this had no bearing on his love for his wife. Second, white collar workers who develop office romances attempt to separate their work lives from their home lives as long as the girlfriend from work recognizes her place (and he his), his family happiness may not be shattered. Of course this is open to debate. 36 Katherine Frank, G-Strings and sympathy: Strip club regulars and male desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002). See Frank for a discussion on the way in which married mens visits to strip clubs in the United States relate to the ways the men practice marriage. 37 Women are supposed to be ignorant of sex, if not virgins when they marry. The importance place on virginity is changing as young people experiment with sex before marriage. The situation was quite different for some of our younger couples. Access to information and ideas about sex and sexuality are now readily accessible through foreign literature, movies, textbooks, internet discussions, and pornography. Whereas it was almost imperative for their grandmothers and mothers to be virgins upon marriage, young women are often not. Cf., Daniele Belanger and Khuat Thu Hong, Young Women Using Abortion in Hanoi, Vietnam Asia Pacific Journal 13(1998). Tine Gammeltoft, Seeking trust and transcendence: sexual risk-taking among Vietnamese youth Social Science and Medicine 55(2002): 483-496. 38 Most information on sex focused on the biology of reproduction and family planning to the exclusion of discussions on sexuality. 39 More than one female respondent was scared the first time they had sexual intercourse. Many found the experience quite painful; typically there was no foreplay and intercourse was often forced. 40 None of the couples had sex when the wife was menstruating; it is considered unhealthy. Women reported that, for the most part, their husbands do leave them alone if they tell their husbands they are too tired or too weak to have sex. However, stating that she did not want to have sex was not viewed by husbands as a legitimate reason for not having sex. 41 For additional research on marital sexuality see: Ha Vu, The Harmony of family and the silence of women: Sexual behavior among married women in two northern rural areas in Vietnam (n.d.) and Phan Thi Thu Hien, Sexual Coercion within Marriage. 42 Although sexual incompatibility was also cited as reason some wives seek extramarital relationships, they do not receive the same amount of social sympathy and understanding as men because women are not suppose to desire sex. For example, one of our female informants explained one of her male neighbors extramarital sexual relationship in terms of his need to satisfy his instinctual desire whereas she explained a married women friends extramarital relations in terms of her bad character. 43 Women are not criticized for no longer wanting to have sex, especially by other women. The euphemisms they use (too weak, too tired, unhealthy, sick children, too old) to reject their husbands advances enables wives to justify not engaging in act they may not enjoy (if they ever did). 44 The Red River Delta, where Hanoi is situated, has one of the highest population densities in the world. In 1995, the per capita floor area of housing in Hanoi was five square meters, but roughly one-third of the

25

citys population had less than three square meters of living space Michael A. DiGregorio, Terry Rambo, and Masayuki Yanagisawa, Clean, Green, and Beautiful: Environment and Development under the Renovation Economy in. Postwar Vietnam: Dynamics of a Transforming Society, ed. Hy V. Luong (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003): 190. 45 Lisa BW Drummond, 2000. Street Scenes: Practices of public and private space in urban Vietnam Urban Studies, Edinburgh 37(2000): 9. 46 See Nguyen-vo Thu huong, Governing Sex: Medicine and Governnmental Intervention in Prostitution, in Gender, Household, State: Doi Moi in Viet Nam. eds., Jayne Werner and Daniele Belanger (Ithaca, New York: Southeast Asia Program Publications, 2002) and Nguyen-Vo Thu Huong 1998. 47 These sexual services could range from hugging, kissing, strip tease, fondling to sexual intercourse. Evelyne Micollier, Introduction in Sexual Cultures in East Asia: The social construction of sexuality and sexual risk in a time of AIDS, ed. Evelyn Miccolier (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004): xiii-xxv. Evelyne Micollier, 2004b. Social Significance of Commercial Sex Work in The social construction of sexuality and sexual risk in a time of AIDS, ed. Evelyn Miccolier (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004): 3-22. 48 See Catherine Earl, Leisure and social mobility in Ho Chi Minh City in Social Inequality in Vietnam and the Challenges to Reform, ed. Philip Taylor (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2003) and Drummond 2002. 49 Walters provides qualitative and quantitative evidence demonstrating the economic value of prostitution to the Vietnamese economy at many levels. Ian Walters, Dutiful Daughters and Temporary Wives: Economic Dependency on Commercial Sex in Vietnam in The social construction of sexuality and sexual risk in a time of AIDS, ed. Evelyn Miccolier (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004): 76-97. 50 Not all of the sexualized leisure involves sexual intercourse. Rather, it can range from having a particularly attentive waitress to one who offers to meet a client later at another location. Yet, it is in these spaces where opportunities for engaging in sexual intercourse present themselves. 51 Nguyen Cu street on the other side of the Choung Duong Bridge leading out of Hanoi and the road perpendicular to it running along the Red River are lined with newly built skinnies, most of which are nha nghis [rest houses] providing rooms for rent and/or girls and men. Nguyen Cu street is so infamous men tease each other with the joke, Have you been to see Ong Cu [Mr. Cu] yet? (The street was named after a person named Nguyen Cu). 52 In the early 1990s karaoke bars were principally places where friends could go to sing. Some karaoke became known as karaoke om [hugging karaoke] where waitresses would keep the male singers company. Men used to tease each other by asking whether they had karaoke arm Gradually some businesses, big and small, began to provide private rooms for their male clients to sing in private with pretty girls. Some bia hoi [fresh beer] establishments became bia om [hugging beer] places but these are public and not a popular as the karaoke om. (Yet, not all karaoke provide girls). 53 Cafs serving coffee in the front room may well provide private rooms in the back for those in the know. Because the clients visiting these private rooms are usually married, but not to each other, an employee or owner of the caf will turn the patrons motorcycles around so the license plates cannot be seen from the street, preventing suspicious husbands and wives from finding cheating spouses. 54 For a detailed description of the different kinds of sex workers in Hanoi, the kind of the establishments they work in, and the range in cost, see, Trung Nam Tran, et al. Drug Use, sexual behaviors and practices. 55 The ability to have places to go to be intimate with someone is remarkable, particularly when contrasted to the 1960 and 1970s when it was difficult to kiss and hug your girlfriend because there was no place to go to do it and the Youth Union patrolled the streets keeping a lookout for transgressive behavior. One of my informants was told to go home when he was caught with his arm around his girlfriend while sitting on a public bench. 56 Judith Butler, Judith 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990). Masculinity can be viewed as a series of practices that exist within a larger system of gender relations rather than as an identity or entity unto itself. R. W. Connell, Masculinities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). 57 The Indochina wars, socialist efforts to rule the Vietnamese populace, and Doi Moi have impacted the ways in which men and women relate to each other and seek to identify with prevailing gender identities. 58 See Catherine Earl, Leisure and social mobility in Ho Chi Minh City. 59 For studies on the relationship between migration and HIV see: C. Campbell, Migrancy, Masculine Identities and AIDS: The Psychosocial Context of HIV Transmission on the South African Gold Mines,

26

Social Science and Medicine 45 (1997): 273-281. J. Hirsch, J. Higgins, M. Bentley, and C. Nathanson, The Social Constructions of Sexuality: Marital Infidelity and Sexually Transmitted Disease-HIV Risk in a Mexican Migrant Community, American Journal of Public Health 92 (2002): 1227-1237. 60 Our suggestions are based upon the assumption that, Whom one is permitted to have sex with, in what ways, under what circumstances, and with what specific outcomes are never random; such possibilities are defined through explicit and implicit rules imposed by the sexual cultures of a specific community and by underlying power relations (Richard Parker, Regina Maria Barbosa, Peter Aggleton, Framing the Sexual Subject: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality, and Power (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000): 7. 61 Family Health International FHI, Rethinking Prevention Interventions for male Clients of Sex Workers: Experiences From Vietnam (Hanoi: A Consultation Report 1-2, December 2004).

27

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Reading Between The LiesDocument11 pagesReading Between The LiesFraitoru CrystyanNo ratings yet

- Tok Essay Draft 1Document6 pagesTok Essay Draft 1rotsro50% (2)

- Men and Women Show Distinct Brain Activations During Imagery of Sexual and Emotional InfidelityDocument9 pagesMen and Women Show Distinct Brain Activations During Imagery of Sexual and Emotional InfidelityGiulio Annicchiarico LoboNo ratings yet

- The Shocking Truth About Trust - The+Shocking+Truth+About+Trust+eBook+2015Document36 pagesThe Shocking Truth About Trust - The+Shocking+Truth+About+Trust+eBook+2015GuitargirlMimi100% (1)

- Can Mistress Be Held Liable Under Ra 9262Document3 pagesCan Mistress Be Held Liable Under Ra 9262Fatima Wilhenrica VergaraNo ratings yet

- Don't Cheat, Be Happy. Self-Control, Self-Beliefs, and Satisfaction With Life in Academic HonestyDocument7 pagesDon't Cheat, Be Happy. Self-Control, Self-Beliefs, and Satisfaction With Life in Academic HonestyjairovelasquezmorenoNo ratings yet

- Ìwòrì ÒsáDocument15 pagesÌwòrì ÒsáOmorisha ObaNo ratings yet

- It Takes A Village: Academic Dishonesty & Educational OpportunityDocument3 pagesIt Takes A Village: Academic Dishonesty & Educational OpportunityAadarsh RamakrishnanNo ratings yet

- How to Attract and Seduce MILFsDocument41 pagesHow to Attract and Seduce MILFsDaniyal Abbas50% (2)

- Behavior Changes That May Signal A Cheating SpouseDocument2 pagesBehavior Changes That May Signal A Cheating SpouseGustavo HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Human Sexuality in A World of Diversity 6th Canadian Edition RathusDocument29 pagesTest Bank For Human Sexuality in A World of Diversity 6th Canadian Edition Rathuspennypowersxbryqnsgtz100% (25)

- Academic Cheating ResearchDocument33 pagesAcademic Cheating ResearchNeol SeanNo ratings yet

- Lies in The Great GatsbyDocument3 pagesLies in The Great GatsbyBecca LevyNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument40 pagesUntitled DocumentVee Jay DeeNo ratings yet

- Book Review - FreakonomicsDocument5 pagesBook Review - FreakonomicsJasfher CallejoNo ratings yet

- Perry Belcher - Secret Selling System - Nerd NotesDocument118 pagesPerry Belcher - Secret Selling System - Nerd Notesgeorge100% (4)

- Journey With Wisdom - SirocnotesDocument15 pagesJourney With Wisdom - SirocnotesSuccessNo ratings yet

- Aggression NotesDocument10 pagesAggression NotesKayleigh EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Anarchism & Polyamory (Dysophia 1)Document64 pagesAnarchism & Polyamory (Dysophia 1)DysophiaNo ratings yet

- Personality, Situation, and Infidelity in Romantic RelationshipsDocument202 pagesPersonality, Situation, and Infidelity in Romantic RelationshipsJlazy bigNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Cheating in RelationshipsDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Cheating in Relationshipsqhujvirhf100% (1)

- Viñas Vs ViñasDocument12 pagesViñas Vs ViñasAnaliza MatildoNo ratings yet

- Enacting The AntiDocument9 pagesEnacting The AntimaryryomaNo ratings yet

- Ebook PDF Communication Principles For A Lifetime 7th Edition PDFDocument42 pagesEbook PDF Communication Principles For A Lifetime 7th Edition PDFvenus.roche638100% (34)

- Secrets of A Strong Married LifeDocument62 pagesSecrets of A Strong Married LifeJoey ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Marriage Conflict Note 1Document18 pagesMarriage Conflict Note 1Johnson DanielNo ratings yet

- PDF - Power of Silence After Break UpDocument18 pagesPDF - Power of Silence After Break UpExBackExpertise50% (2)

- Motivational SpeechesDocument5 pagesMotivational SpeechesAnonymous UbgxbiyPXP100% (1)

- Philippines Domestic Violence CaseDocument2 pagesPhilippines Domestic Violence CaseAw LapuzNo ratings yet

- Situation ShipDocument46 pagesSituation ShipEliNo ratings yet