Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acad RB Mercury 20100713 Final

Uploaded by

saradel90Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acad RB Mercury 20100713 Final

Uploaded by

saradel90Copyright:

Available Formats

Issue Brief

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park

Mercury Contamination

at Acadia National Park

Why Mercury Matters at Acadia National Park

While Acadia National Park (NP) is often perceived as a pristine natural area along Maines coast, some of the parks fish and wildlife are contaminated with high levels of mercury. Research has documented that certain fish, amphibians, and even tree swallows from Acadia NP carry heavy burdens of mercury. Mercury levels in these species are high enough to put them at risk for harmful effects, including decreased survival rates. Levels of mercury in some fish sampled also exceeded wildlife and human health consumption thresholds. Mercury concentrations magnify up the food chain and thus diet is the primary pathway for mercury contamination. The major source of mercury in the parks environment is deposition from the atmosphere a result, in part, of emissions from industrial sources in states to the south and west. The National Park Service (NPS) is concerned about the effects of mercury because this airborne pollutant threatens the natural resources the NPS is charged with protecting.

Research indicates that ecosystems at Acadia NP contain elevated levels of mercury, a toxic heavy metal atmospherically transported to the park from distant sources.

How is Mercury Affecting Acadia National Park?

The National Park Service has been engaged in research into the sources, movement, and concentration of mercury in Acadia NP ecosystems for more than two decades. The park is one of the most intensively studied areas for mercury in the United States. Research results consistently indicate elevated and pervasive levels of mercury across Acadia NPs landscape. Mercury is elevated in some of Acadia NPs surface waters (Figure 2), sediments, soils, and biota such as plankton, tadpoles, salamanders, fish, common loons, tree swallows, and bald eagles. Documented effects of observed mercury levels include low growth rate in tree swallow chicks and increased vulnerability of certain fish to predation. Concentrations of mercury in fish from Acadia NP exceeded statewide human health consumption thresholds for sensitive populations, such as women of childbearing age and children. Fish also exceeded mercury thresholds established for fish-eating wildlife such as loons (Figure 3). While the deposition of mercury is ubiquitous across Acadia NPs landscape, much of the research has also focused on which types of landscapes might have higher concentrations of mercury and how mercury cycles through the parks environment. Findings indicated that forested areas act as air filters, raking mercury from the air and collecting it on foliage, which later drops to the ground in rain or snow, or with falling leaves and needles. This process, referred to as throughfall, is

Where Does Mercury Come From?

While there are natural sources of mercury such as volcanoes, human activities have greatly increased the amount of mercury in the environment through processes such as burning coal for electricity, burning mercury-contaminated waste, and the production of chlorine. Once emitted to the air as an elemental or inorganic chemical, mercury can travel great distances before it is eventually returned to the earth by wet (rain, snow), dry (dust, other airborne particles), or occult (cloud, fog) deposition. In the environment, particularly certain types of wetlands, natural biological processes convert these forms of mercury into a toxic, bio-available form called methylmercury. Methylmercury builds-up in organisms and increases in concentration with each level of the food chain through a process called biomagnification (Figure 1). Toxic effects of methylmercury upon wildlife and human health can include reduced reproductive success, impaired growth and development, altered behavior, and decreased survival. There are a few localized factors that contribute to the mercury contamination problem at Acadia NP, including the parks steep slopes, high peaks, and exposure to coastal fog that create an environment conducive to trapping polluted air masses. Furthermore, the park is downwind of many large coal-burning power plants in the Midwestern U.S. Though Maine releases less than a thousandth of a percent of U.S. emissions, airborne mercury is transported from distant sources and deposited into Acadia NP. Additionally, the parks forested areas and abundant surface waters create an environment especially susceptible to mercury contamination. Mercury is a heavy metal but can vaporize easily from land and water surfaces and repeatedly re-enter the atmosphere, particularly during wildfires.

Figure 1. It only takes a very small amount of mercury (Hg) to contaminate an ecosystem and become a significant health threat to humans and wildlife. Through a process called methylation, naturally occurring bacteria act on mercury to create methylmercury, which accumulates in organisms and magnifies in concentration with each level of the food chain. Continued

EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA

June 2010

estimated to be the largest vector of mercury input from the atmosphere to the parks terrestrial ecosystems. The mercury that is washed to the ground with throughfall collects in the soil and eventually moves into streams and lakes. Additional findings from the park show that coniferous forests of spruce, fir, and pine trees capture more mercury from the air than deciduous forests because needles have more surface area to grab the mercury than leaves. In addition, forests that are located on southwest-facing slopes of Acadia NP were hardest hit because they directly intercept polluted air masses drifting eastward across the U.S. Research in two park watersheds indicated events such as fire can have tremendous influence, even decades later, on an areas susceptibility to mercury and other air pollutants. Reconstructing the history of Acadias landscape, researchers showed that the southeast slope of Cadillac Mountain, which burned during a major fire in 1947 and was re-vegetated by deciduous trees, better retains mercury as compared to other unburned areas of the park that flush more mercury into streams. As evidence of this, salamanders living in unburned forests had higher levels of mercury in their bodies than those in the burned areas. The difference between burned and unburned areas can be attributed to increased deposition in coniferous, unburned sites and changes in soil structure and carbon content that influence how mercury is retained and processed in soils. Current ongoing studies include the continued monitoring of wet mercury deposition (1995 present; Figure 4) and a methylmercury risk assessment for park watersheds. Research gaps include the need to document the extent of physiological and ecological implications of elevated mercury concentrations in park wildlife and gain a better understanding of the role of fog in contributing to the mercury deposition burden to the parks ecosystems. Additionally, the NPS hopes to facilitate research on the synergistic effects of climate change on mercury contamination.

Figure 3. The average concentration of mercury in fillets from predator fish (e.g., bass, pickerel) from 11 lakes at Acadia NP exceeded health thresholds established for the safe consumption of fish by humans and wildlife such as loons. Additionally, the average concentration of mercury in whole body fish exceeded the health threshold for wildlife, an important distinction when considering that wildlife are more likely to consume the whole body than humans.

What Are The Implications?

Mercury deposition and its potential toxic effects to wildlife and human health at Acadia NP represent a significant concern for the National Park Service. Park natural resources are threatened by sources of airborne mercury far from national park boundaries. Continued coordination with federal and state regulatory agencies charged with protecting the nations air quality will be essential in the effort to reduce mercury emissions, and thus mercury deposition, from national and international sources the first step toward improved ecosystem conditions.

Figure 4. Wet mercury deposition is monitored weekly at Acadia NP. Data indicate that the current rate of mercury deposition is about 4 times greater than what scientists think rates were before industrialization.

More Information

Acadia National Park Division of Resource Management Phone/Email 207-288-8720 acadia_information@nps.gov

Links & Resources Air Quality in Parks: http://www.nature.nps.gov/air/permits/ARIS/acad/ Acadia NP Air Quality: http://www.nps.gov/acad/naturescience/airquality.htm Figure 2. While mercury concentrations in streams from Acadia NPs Mount Desert Island (MDI) fall within the statewide range, mercury levels in MDI streams are unusually high within the regional context of coastal and Downeast Maine. The vast extent of wetlands within the park provides environments conducive to increased methylation of mercury, likely contributing to greater mercury contamination. EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Acknowledgements Contributing text provided by S.J. Nelson, Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Environmental and Watershed Research at the University of Maine. Edited by Colleen Flanagan, NPS Air Resources Division, Denver, Colorado.

You might also like

- Ecohydrology: Vegetation Function, Water and Resource ManagementFrom EverandEcohydrology: Vegetation Function, Water and Resource ManagementNo ratings yet

- Tugas 4 Pencemaran PantaiDocument16 pagesTugas 4 Pencemaran PantaiMuhagungNo ratings yet

- Zahir2005 PDFDocument10 pagesZahir2005 PDFAndré PérezNo ratings yet

- 11 48 2 PBDocument6 pages11 48 2 PBFRITMA ASHOFINo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document8 pagesLecture 1JosephNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Metal Contamination in Water and Sediment Near A Coal Thermal Power Plant On The Eastern Coast of BangladeshDocument18 pagesA Case Study On Metal Contamination in Water and Sediment Near A Coal Thermal Power Plant On The Eastern Coast of BangladeshAANo ratings yet

- RP Jan 17 2014Document6 pagesRP Jan 17 2014api-249099547No ratings yet

- SC Projectacid RainDocument7 pagesSC Projectacid RainEthan ChengNo ratings yet

- Aquaculture As Source of Environmental CDocument8 pagesAquaculture As Source of Environmental CadegolaadebowalebNo ratings yet

- 5-Seagrass Ecosystems As A Significant Global CarbonDocument6 pages5-Seagrass Ecosystems As A Significant Global CarbonzhaoyuNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature Marine PollutionDocument7 pagesReview of Related Literature Marine Pollutionafmzyywqyfolhp100% (1)

- GBR Best Practice Literature ReviewDocument14 pagesGBR Best Practice Literature ReviewAliciaNo ratings yet

- Mining Background Literature ReviewDocument16 pagesMining Background Literature ReviewMohamed FikryNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0025326X10001852 Main PDFDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0025326X10001852 Main PDFM LYFNo ratings yet

- Chemosphere: Yinka Titilawo, Abiodun Adeniji, Mobolaji Adeniyi, Anthony OkohDocument10 pagesChemosphere: Yinka Titilawo, Abiodun Adeniji, Mobolaji Adeniyi, Anthony OkohAdeniji OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Mercury PoisoningDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Mercury PoisoningvguneqrhfNo ratings yet

- Al-Fasi Et Al.2015 PDFDocument8 pagesAl-Fasi Et Al.2015 PDFUmroh NuryantoNo ratings yet

- MODULE 1 EpmDocument23 pagesMODULE 1 EpmLuckygirl JyothiNo ratings yet

- Heavy Metal Contamination in Water and Fishery Resources in Manila Bay Aquaculture FarmsDocument24 pagesHeavy Metal Contamination in Water and Fishery Resources in Manila Bay Aquaculture FarmsJames DerekNo ratings yet

- DhruviPareek 21060222093 DivA ILCDocument12 pagesDhruviPareek 21060222093 DivA ILCLuNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0269749116303724 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0269749116303724 Mainthb7mjhbxyNo ratings yet

- Effects of UV Radiation On Aquatic Ecosystems andDocument20 pagesEffects of UV Radiation On Aquatic Ecosystems andVIALDA ANINDITA PUTERI SULANDRINo ratings yet

- Arsenic Pollution of Subsurface Water (1075)Document14 pagesArsenic Pollution of Subsurface Water (1075)rayonneeemdyNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument4 pagesProjectBeing DannieNo ratings yet

- Air and Water Pollution 1100 Word APA Format With References ADocument6 pagesAir and Water Pollution 1100 Word APA Format With References AAndré Mori EspinozaNo ratings yet

- What Is Ocean Pollution?: How Much Money Can A Solar Roof Save You in Malaysia?Document7 pagesWhat Is Ocean Pollution?: How Much Money Can A Solar Roof Save You in Malaysia?Jega SkyNo ratings yet

- Research Acid Rain Final MidtermDocument10 pagesResearch Acid Rain Final MidtermKey an FababaerNo ratings yet

- Using Risk Ranking of Metals To Identify Which Poses The G - 2014 - EnvironmentaDocument7 pagesUsing Risk Ranking of Metals To Identify Which Poses The G - 2014 - EnvironmentaLili MarleneNo ratings yet

- Groundwater Pollution ThesisDocument7 pagesGroundwater Pollution Thesislanasorrelstulsa100% (2)

- No. 6 Ocean Acidification Foresight ReportDocument98 pagesNo. 6 Ocean Acidification Foresight ReportHerbert BillNo ratings yet

- McCullough Et Al IMWA 2009Document5 pagesMcCullough Et Al IMWA 2009etsimoNo ratings yet

- Eutrophication - "The Process by Which A Body of Water Acquires A High ConcentrationDocument4 pagesEutrophication - "The Process by Which A Body of Water Acquires A High ConcentrationMarkNo ratings yet

- Impact of Mercury On The EnvironmentDocument10 pagesImpact of Mercury On The EnvironmentJohn DiasNo ratings yet

- Thesis Synopsis - Farhana D3 CorrectedDocument8 pagesThesis Synopsis - Farhana D3 CorrectedSadman38No ratings yet

- Introduction To Marine PollutionDocument34 pagesIntroduction To Marine PollutionPepeNo ratings yet

- 1st Q Worksheet 1 Common Environmental IssuesDocument10 pages1st Q Worksheet 1 Common Environmental IssuesCornelio T. BavieraNo ratings yet

- Marine Pollution. ILEXDocument5 pagesMarine Pollution. ILEXofFlickNo ratings yet

- The Negative Impact of Aral Sea Construction On The Health of The PopulationDocument2 pagesThe Negative Impact of Aral Sea Construction On The Health of The PopulationEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- FYP Crosscheck 2019 LandscapeDocument42 pagesFYP Crosscheck 2019 LandscapeSara JangNo ratings yet

- Bergland Pedersenand Wyller ECOCOM2019Document20 pagesBergland Pedersenand Wyller ECOCOM2019Beta Indi SulistyowatiNo ratings yet

- Environmental ScienceDocument3 pagesEnvironmental Sciencekimanid488No ratings yet

- Research Paper On WetlandsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Wetlandsfvgbhswf100% (1)

- TMP BE92Document7 pagesTMP BE92FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Marine Pollution-Documentary Script: October 2005Document9 pagesMarine Pollution-Documentary Script: October 2005Rubyjayne Kate ANINONNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18: Water PollutionDocument8 pagesChapter 18: Water Pollutionhoocheeleong234No ratings yet

- Natural Pollution Caused by The Extremely Acidic Crater Lake Kawah Ijen, East Java, IndonesiaDocument7 pagesNatural Pollution Caused by The Extremely Acidic Crater Lake Kawah Ijen, East Java, IndonesiaCindy Nur AnggreaniNo ratings yet

- Fireworks and New Hampshire's Lakes: Potential For PollutionDocument2 pagesFireworks and New Hampshire's Lakes: Potential For PollutionDedyTo'tedongNo ratings yet

- 2005, Epiphytic Diatoms of The Tisza River, KisköreDocument11 pages2005, Epiphytic Diatoms of The Tisza River, Kiskörekenanga sariNo ratings yet

- Information About Dead ZoneDocument6 pagesInformation About Dead ZoneJaam Awais HayatNo ratings yet

- 1 Human Impact On EcosystemDocument25 pages1 Human Impact On EcosystemRoopsia Chakraborty100% (1)

- Regional Studies in Marine Science: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesRegional Studies in Marine Science: SciencedirectHasna Nurul Muthi'ahNo ratings yet

- PaperNumber18 PDFDocument10 pagesPaperNumber18 PDFwan marlinNo ratings yet

- Environmental PollutionDocument10 pagesEnvironmental PollutionPragya AgrahariNo ratings yet

- What Is Marine PollutionDocument14 pagesWhat Is Marine PollutionEMNo ratings yet

- Et Ls 20180117Document10 pagesEt Ls 20180117Jean Bea WetyNo ratings yet

- XeroxpaperDocument2 pagesXeroxpaperEunice GandicelaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Ocean AcidificationDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Ocean Acidificationxwrcmecnd50% (2)

- Baishaw 2007Document24 pagesBaishaw 2007Rami KettoucheNo ratings yet

- ChesapeakebaycleanupDocument3 pagesChesapeakebaycleanupapi-349036110No ratings yet

- Research Paper PollutionDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Pollutionjsllxhbnd100% (1)

- ACAD Visitor Impacts RSRCBRF 8-4-09Document2 pagesACAD Visitor Impacts RSRCBRF 8-4-09saradel90No ratings yet

- Forest Pest Poster BOHA 20101113 SimpleDocument1 pageForest Pest Poster BOHA 20101113 Simplesaradel90No ratings yet

- Forest Pest Poster FINAL 20100701Document1 pageForest Pest Poster FINAL 20100701saradel90100% (1)

- BioBlitzPoster SDelheimer 20100708Document1 pageBioBlitzPoster SDelheimer 20100708saradel90No ratings yet

- Integrating Bike Share Programs Into Sustainable Transportation System CPB Feb11Document4 pagesIntegrating Bike Share Programs Into Sustainable Transportation System CPB Feb11siti_aminah_25No ratings yet

- Vinyl Chloride 2Document2 pagesVinyl Chloride 2Novia Mia YuhermitaNo ratings yet

- Checklist For Good Ventilation For The FoundariesDocument2 pagesChecklist For Good Ventilation For The FoundariesRamakrishnan SitaramanNo ratings yet

- Semiconductor Wastewater Treatment Using Tapioca Starch As A Natural CoagulantDocument9 pagesSemiconductor Wastewater Treatment Using Tapioca Starch As A Natural Coagulanthuonggiangnguyen3011No ratings yet

- Why Plastics Are Important DIGITAL 1Document2 pagesWhy Plastics Are Important DIGITAL 1Naishal PatelNo ratings yet

- LaMotte 3308 Chlorine OCTA-Slide Kit InstructionsDocument2 pagesLaMotte 3308 Chlorine OCTA-Slide Kit InstructionsPromagEnviro.comNo ratings yet

- Separate Sewerage SystemDocument2 pagesSeparate Sewerage SystemDaaZy LauZah50% (2)

- Iarc 2016 Riesgos Cambio Climatico Ingles DefDocument3 pagesIarc 2016 Riesgos Cambio Climatico Ingles DefCristina Díaz ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Gobal WarmingDocument7 pagesGobal WarmingKamlesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- MSDS LC EndothermicDocument3 pagesMSDS LC EndothermicSantiago J. ramos jrNo ratings yet

- Index: Composting Facility Log of OperationsDocument13 pagesIndex: Composting Facility Log of OperationsJesus Alberto CruzNo ratings yet

- Bloom's TaxonomyDocument3 pagesBloom's TaxonomyNgyen Anh Ly0% (1)

- Environmental StudiesDocument3 pagesEnvironmental StudiesMithileshNo ratings yet

- Hypogear 80W-90 - BP Australia Pty LTDDocument5 pagesHypogear 80W-90 - BP Australia Pty LTDBiju_PottayilNo ratings yet

- Volatile Organic Compounds in Various Sample Matrices Using Equilibrium Headspace AnalysisDocument25 pagesVolatile Organic Compounds in Various Sample Matrices Using Equilibrium Headspace AnalysisBianny Gempell Velarde PazNo ratings yet

- Etyl Mercaptan MSDSDocument24 pagesEtyl Mercaptan MSDSmostafa_1000100% (1)

- Appendix 5 Foundation Method StatementDocument15 pagesAppendix 5 Foundation Method StatementTAHER AMMARNo ratings yet

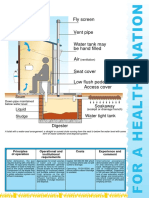

- SA AquaPrivyDocument1 pageSA AquaPrivygkumar77100% (2)

- Biomass Conversion TechnologiesDocument3 pagesBiomass Conversion TechnologiesYoy Sun Zoa0% (1)

- UP Govt DPF For 5 Star HotelDocument88 pagesUP Govt DPF For 5 Star HotelShankar SanyalNo ratings yet

- Soaps and DetergentsDocument24 pagesSoaps and Detergentsઅવિનાશ મીણાNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 Compo - 1term 2021 - 2022Document5 pagesGrade 9 Compo - 1term 2021 - 2022Amera AlmutireNo ratings yet

- Sustainability, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipDocument564 pagesSustainability, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipAmit Kumar100% (1)

- Conventional Pineaple Production KenyaDocument41 pagesConventional Pineaple Production KenyaOlajide Emmanuel OlorunfemiNo ratings yet

- Emrald Mall, LucknowDocument32 pagesEmrald Mall, LucknowSushma SharmaNo ratings yet

- 2540Document7 pages2540pollux23No ratings yet

- 1.1 Palm Oil MillDocument31 pages1.1 Palm Oil MillChee Yen ChiaNo ratings yet

- Waterless DyeingDocument2 pagesWaterless DyeingChaitali Debnath100% (1)

- Diagnóstico Ambiental de YeclaDocument48 pagesDiagnóstico Ambiental de YeclaMuseo Arqueológico Municipal de YeclaNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis, Md. HasanuzzamanDocument159 pagesPHD Thesis, Md. Hasanuzzamandedi sanatraNo ratings yet

- Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincFrom EverandPeriodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (137)

- Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessFrom EverandAlex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessNo ratings yet

- Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse”From EverandLessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse”Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseFrom EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (69)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- Water to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct, and the Rise of Los AngelesFrom EverandWater to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct, and the Rise of Los AngelesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandFrom EverandChesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (38)

- Fire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness LookoutFrom EverandFire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness LookoutRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (142)

- The Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterFrom EverandThe Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterNo ratings yet

- Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and CivilizationFrom EverandWater: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and CivilizationRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (37)

- Smokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersFrom EverandSmokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersNo ratings yet

- The Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsFrom EverandThe Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (65)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldFrom EverandThe Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (595)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldFrom EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- When You Find Out the World Is Against You: And Other Funny Memories About Awful MomentsFrom EverandWhen You Find Out the World Is Against You: And Other Funny Memories About Awful MomentsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (35)