Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Auditor Changes and Discretionary Accruals: Mark L. Defond, K.R. Subramanyam

Uploaded by

Titas RudraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Auditor Changes and Discretionary Accruals: Mark L. Defond, K.R. Subramanyam

Uploaded by

Titas RudraCopyright:

Available Formats

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 213 740 5017; fax: 213 747 2815; e-mail: krs@almaak.usc.

edu

Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

Auditor changes and discretionary accruals

Mark L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam*

Leventhal School of Accounting, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1421, USA

Received 1 February 1997; received in revised form 1 August 1998

Abstract

In a sample of auditor change rms we nd that discretionary accruals are income

decreasing during the last year with the predecessor auditor and generally insignicant

during the rst year with the successor. In addition, the income decreasing discretionary

accruals are concentrated among rms expected to have greater litigation risk. These

ndings are consistent with litigation risk concerns providing incentives for auditors to

prefer conservative accounting choices, and with managers dismissing incumbent audi-

tors in the hope of nding a more reasonable successor. However, we cannot rule out

nancial distress as a potential alternative explanation for our results. 1998 Elsevier

Science B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classication: L84; M40; M41

Keywords: Auditing; Auditor-client realignment; Auditor changes; Discretionary ac-

cruals; Litigation risk; Auditor conservatism; Earnings management

1. Introduction

Auditor changes have received considerable attention from both regulators

and academics. The regulators interests are due to a concern that auditor

changes are motivated by management opportunism. For example, the Secur-

ities and Exchange Commission (SEC) states it is concerned with auditor

changes that involve

2

the search for an auditor willing to support a proposed

accounting treatment designed to help a company achieve its reporting

objectives even though that treatment might frustrate reliable reporting

0165-4101/98/$ see front matter 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 1 6 5 - 4 1 0 1 ( 9 8 ) 0 0 0 1 8 - 4

Other examples of regulatory interest include US Congress reports of the Moss Committee (US

Congress, 1976), the Metcalf Committee (US Congress, 1977a,b), and the Dingell Committee (US

Congress, 1985), the AICPA Cohen Commission (Commission on Auditors Responsibilities, 1978),

and the Treadway Commission (National Commission on Fraudulent Financial Reporting, 1987).

` Studies that do not nd evidence consistent with a management opportunistic explanation for

auditor changes include Chow and Rice (1982), Smith (1986), Johnson and Lys (1990), Francis and

Wilson (1988), and DeFond (1992).

(Securities and Exchange Commission, 1988). In spite of this concern, academic

research nds little or no evidence of opportunistically motivated auditor

changes.` This paper investigates an alternative explanation for auditor changes.

Specically, we test implications from theory suggesting that auditor changes

are motivated by auditors preferences for conservative accounting choices.

Analytical work by Dye (1991) and Antle and Nalebu (1991) concludes that

auditor changes can occur when managers and auditors hold legitimate diver-

gent beliefs regarding the appropriate application of GAAP. Such disagree-

ments are most likely to occur when the predecessor auditor believes that the

appropriate application of GAAP results in lower earnings than the application

favored by management (Antle and Nalebu, 1991). The auditors desire to

reduce reported earnings, however, is not necessarily a response to manage-

ments eorts to opportunistically increase reported earnings. The audi-

torclient conict may instead stem from the auditors incentives to report

conservatively. This perspective acknowledges that auditors also have ac-

counting choice preferences that are motivated by incentives (Magee and Tseng,

1990; DeAngelo et al., 1994), and that the reported accounting choices are the

joint outcome of both the clients and the auditors preferences.

An incentive likely to motivate auditors to prefer conservative accounting

choices is client litigation risk. This is because conservative accounting choices

are expected to protect the auditor against future litigation and the potential

damages arising therefrom. The extent of conservatism, however, is expected to

dier across auditors based on factors such as individual assessment of client

risk and relative risk propensities. If management believes the incumbent audi-

tors accounting choice preferences are more conservative than those expected

from the average auditor, management has an incentive to dismiss the incum-

bent auditor in hopes of nding a more reasonable successor.

Three empirical implications are generated by the above arguments. First, if

the predecessor auditor prefers conservative accounting choices, discretionary

accruals in the last year with the predecessor auditor are expected to be income

decreasing. Second, if litigation risk motivates the auditors accounting choice

preferences, income decreasing discretionary accruals will be more pronounced

among rms that are likely to pose the greatest litigation risk threat to the

auditor. Finally, if the manager is correct in believing that the incumbent

auditor is more conservative than the average auditor, we expect discretionary

36 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

` Krishnan (1994) also nds evidence of auditor conservatism in a study examining audit opinions

around the time of auditor changes.

accruals in the rst year with the successor auditor to be less income decreasing

than in the last year with the predecessor. We explore these implications by

examining the behavior of discretionary accruals in a sample of auditor change

rms.

Our sample consists of 503 rms that change auditors during the four-year

period from 1990 to 1993. Discretionary accruals are measured using a variation

of the model in Jones (1991) used by DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994). Our initial

analysis nds that discretionary accruals are insignicantly dierent from zero

two years prior to the auditor change but, consistent with expectations, become

signicantly income decreasing during the last year with the predecessor audi-

tor. We also nd that, while discretionary accruals continue to be negative

during the rst year with the successor auditor, the magnitudes are much lower.

These ndings are consistent with auditor changes being precipitated by auditor

conservatism.`

We investigate the auditors incentives to prefer conservative accounting

choices in the last year with the predecessor auditor by partitioning our sample

based upon characteristics expected to be associated with client litigation risk.

Consistent with expectations, we nd that negative discretionary accruals are

concentrated among the sample partitions that are expected to pose the greatest

client litigation risk threat to the auditor. Specically, we nd discretionary

accruals in the last year with the predecessor are more negative for clients that

receive a modied opinion from the predecessor auditor, have a Big 6 prede-

cessor auditor, change to a non-Big 6 successor auditor, or report a disagree-

ment or auditor resignation in the auditor-change 8K.

A potential alternative explanation for our ndings is that the negative

discretionary accruals found in our analysis are attributable to poor perfor-

mance among the sample rms. Descriptive information on earnings, cash ows

and Altmans z-score indicates our sample rms are nancially distressed

around the time of the auditor change. Prima facie the presence of distress is

consistent with our conjecture. That is, nancial distress increases litigation risk,

which results in the auditors preference for conservative accounting, which then

results in the client dismissing the incumbent auditor in order to nd a more

reasonable successor. However, nancial distress may also precipitate auditor

changes for reasons unrelated to conservative accounting choices. Dechow et al.

(1995) document that discretionary accruals are biased in rms with extreme

performance. Therefore, the negative discretionary accruals in our sample may

be mechanically induced by nancial distress.

In addition, there are alternative economic explanations for our results. For

example, auditors may respond to the increased litigation risk posed by dis-

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 37

" DeAngelo et al. (1994) also conjecture that income reducing choices among distressed rms may

be due to auditors forcing managers to take noncash write-os, which is consistent with our ndings.

Other reasons for managers reducing earnings suggested by DeAngelo et al. are union negotiations

(Liberty and Zimmerman, 1986; DeAngelo and DeAngelo, 1991), and lobbying for import relief

(Jones, 1991). However, these explanations are less likely to be distress induced.

` An alternative explanation is that the economic circumstances of the client change in the rst

year with the successor in a manner that lowers litigation risk. However, empirical evidence is not

consistent with this explanation. For example, analysis of cash ows indicates that the nancial

health of the rms do not change over the periods of analysis, and the Altmans z-score indicates the

rms are, on average, becoming more distressed in the rst year with the successor (see Table 1).

tressed clients by simply resigning from the engagement (MacDonald, 1997).

Alternatively, distressed rms may undergo structural changes that induce them

to realign with auditors who are better matched to their changing needs

(Johnson and Lys, 1990). Distress is also associated with management change,

which is associated with income decreasing accruals (Pourciau, 1993). Another

potential alternative explanation for our ndings is that, independent of audi-

tors incentives, management may also have incentives to reduce earnings in

times of poor nancial health. For example, DeAngelo et al. (1994) suggest that

management of distressed companies may reduce reported earnings in order to

convince lenders that management is serious about streamlining operations."

Therefore, it is important to perform tests that will distinguish whether the

negative discretionary accruals in our sample genuinely result from auditor

conservatism, or whether they are attributable to other factors related to poor

performance.

Two types of tests are performed to ascertain the credibility of our initial

analysis. Our rst set of tests control for the potential eects of various con-

founding factors on our estimates of discretionary accruals. We rst conduct

univariate tests that control for the mechanical eects of nancial performance

on discretionary accruals estimated using the Jones model. These tests consist of

orthogonalizing discretionary accruals to cash ows, a cash ow matched pairs

test, and a test that excludes sample rms in the extreme deciles of earnings.

Consistent with our initial results, we nd that discretionary accruals are

signicantly negative in the last year with the predecessor auditor. We also nd

that the magnitudes of the discretionary accruals decline, and that discretionary

accruals in the rst year with the successor auditor become generally insignic-

ant. The drop in magnitude of the discretionary accruals in the last year with the

predecessor auditor is consistent with nancial distress impacting, but not

explaining, our unconditioned estimates from the Jones model. The generally

insignicant discretionary accruals found in the rst year with the successor

auditor are consistent with the client nding a successor auditor that is less

conservative than the predecessor auditor.`

38 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

We also perform multivariate tests that control for several factors that could

potentially confound our results such as management changes, corporate re-

structurings, and the eects of potentially omitted correlated variables identied

in Johnson and Lys (1990). We perform these tests alone, and in conjunction

with our univariate tests that control for cash ows and extreme earnings. The

results indicate our ndings are robust to these additional controls. In addition,

our results are not replicated when we randomly decompose accruals to gener-

ate the discretionary component (Guay et al., 1996).

Our second set of tests look for evidence that corroborates the conclusions we

draw from examining discretionary accruals. We do this by examining four

accounting measures that are subject to management discretion: special items,

the provision for bad debts, amortization of intangibles, and a composite

measure of discrete accounting method choices. With respect to each of these

measures, we nd that, on average, our sample rms make income decreasing

changes during the last year with the predecessor auditor. In addition, of the

rms making income decreasing changes during the last year with the prede-

cessor, the proportion that switch back to relatively less conservative ac-

counting choices during the rst year with the successor auditor generally

exceeds the proportion that make further conservative changes. These ndings

present suggestive evidence that corroborates our results from examining dis-

cretionary accruals.

Taken together, our conjecture that auditor conservatism can lead to auditor

dismissals is robust to the above tests. We nd that our results are not driven by

management change, corporate restructuring or by the variables that explain

auditor changes in Johnson and Lys (1991), and the tests that control for

performance indicate our results are not mechanically induced by nancial

distress. In addition, nding that discretionary accruals are negative during the

last year with the predecessor auditor and insignicant during the rst year with

the successor auditor is not consistent with management attempting to reduce

earnings in order to convince lenders they are streamlining operations. This is

because nancial distress, according to the Altman z-score, actually increases

slightly during the rst year with the successor. Finally, since most of our sample

consists of client-initiated auditor changes that report signicant negative

discretionary accruals, our results are not solely attributable to auditor

resignations. However, we can never be sure that we completely control for the

eects of distress. And, given that distress is a potential explanation for auditor

changes even in the absence of auditor conservatism, we cannot rule out that

poor performance among our sample rms may at least partially explain our

ndings.

In summary, our ndings present evidence on the role of discretionary

accruals in auditor change decisions. The results are consistent with theory

suggesting auditor change is motivated by divergent beliefs among the auditor

and management concerning the appropriate application of GAAP and that the

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 39

reported accounting choices are the joint outcome of both the management and

the auditors preferences (Dye, 1991; Antle and Nalebu, 1991). Our ndings

also provide further evidence on the relation between accruals and auditor

concerns about litigation risk (Lys and Watts, 1994). Finally, our paper contrib-

utes to the earnings management literature by suggesting that the external

auditor acts as a constraint to managerial discretion regarding accounting

choice (Becker et al., 1998; Francis et al., 1996).

2. Motivation

The role of independent auditing is to attest to managements appropriate

application of GAAP. However, because the interpretation of GAAP requires

professional judgement, management and auditors (or two dierent auditors)

can hold legitimate divergent beliefs regarding its application (Magee and

Tseng, 1990). This implies that audited nancial statements are ultimately the

outcome of negotiations between management and the incumbent auditor

(Antle and Nalebu, 1991; Dye, 1991). While most auditorclient negotiations

are expected to end in amicable compromise, Dye (1991) concludes that the

disagreements involved in some negotiations lead to auditor changes. Though

empirically only a small portion of auditor change rms report auditor-client

disagreements in their auditor change 8-Ks, prior research reports a tendency

for auditors and clients to circumvent the disclosure requirement (Smith and

Nichols, 1982; DeFond and Jiambalvo, 1993). An incentive to underreport

disagreements is that such disclosure is found to result in share price declines

(Smith and Nichols, 1982).

Antle and Nalebu (1991) observe that auditorclient disputes that lead to

auditor changes are most likely to occur when the auditor believes that the

appropriate application of GAAP results in a more conservative presentation of

nancial performance than the application favored by management. This is

consistent with DeFond and Jiambalvo (1993), who nd that auditor-client

disagreements reported in 8-Ks are almost always cases where the auditor insists

on an accounting treatment that results in lower earnings than the accounting

treatment preferred by management. In addition, the auditors accounting

preferences nearly always prevail over those of management because auditors

must disclose in their opinion those cases where management insists on imple-

menting an accounting choice that contradicts the auditors judgement

(DeFond and Jiambalvo, 1993).

Magee and Tseng (1990) point out that, like management, auditors also have

accounting choice preferences that are motivated by incentives. An incentive

that is expected to motivate auditors to prefer conservative accounting choices

is litigation risk. Krishnan and Krishnan (1997) point out that prior literature

identies several ways in which auditors respond to litigation risk, including

40 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

' Matsumura et al. (1997) show that heterogeneity in auditor behavior is a necessary condition for

auditor change.

audit plan and audit fee adjustments (Pratt and Stice, 1994; Simunic and Stein,

1996), and increased issuance of modied opinions (Krishnan and Krishnan,

1996). We conjecture that auditors are also likely to respond to litigation risk

by insisting that their clients make conservative accounting choices. This is

because income reducing accounting choices are expected to reduce the audi-

tors litigation exposure. For example, Lys and Watts (1994) report that

clients are more likely to be sued when total accruals are relatively income

increasing. Similarly, St. Pierre and Anderson (1984) report that while

auditors are frequently sued for allowing income overstatements, they nd no

cases of auditors being sued for allowing income understatements. In addition,

Kellogg (1979) nds that courts are more likely to award damages for accruals

that overstate (as opposed to understate) earnings and assets. Taken together,

these studies suggest that auditors are less likely to be sued, or incur damages

if they are sued, if they are associated with nancial statements that understate

(rather than overstate) rm performance. Thus, litigation risk is an incentive

that is expected to induce auditors to prefer accounting choices that reduce

earnings.

The above arguments suggest that auditor changes are triggered by the

predecessor auditors preference for income decreasing accounting choices, and

that a likely cause of the auditors conservatism is client litigation risk. When

management believes that the incumbent auditor is more conservative than the

average auditor, management will dismiss the incumbent in hopes of obtaining

a less conservative successor. The successor auditor may be willing to adopt

a less conservative stance than the predecessor because auditors are expected to

dier in their risk assessments and/or risk propensity (Magee and Tseng, 1990;

Balachandran and Ramakrishnan, 1987; Simunic and Stein, 1990).' These

arguments imply that auditor changes are likely to be preceded by a year in

which discretionary accounting choices are income decreasing. If the auditors

conservatism is a reaction to client litigation risk, we also expect an association

between income decreasing discretionary accruals and the client rms most

likely to pose a litigation risk threat to the auditor. Finally, if management

expectations are rational, we expect the successor auditor to be less conservative

on average with respect to accounting choice preferences. Thus, we expect

discretionary accruals in the rst year with the successor to be less negative than

those in the last year with the predecessor. We explore these implications by

examining discretionary accruals and changes in factors expected to impact

client litigation risk and discretionary accruals among a sample of auditor

change rms.

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 41

` Compustat auditor codes distinguish the identities of the top 24 largest accounting rms

(including the Big 6). This group approximates the population of all international, national and large

regional audit rms. All other audit rms are combined into a single auditor code (9). Due to this

coding convention, auditor changes among these smaller auditors are excluded from our sample. In

addition, we delete all observations from our sample that relate to the mergers of Deloitte Haskins

& Sells with Touche Ross & Co. and Arthur Young with Ernst & Whinney. As an additional

precaution we conduct a sensitivity check where we delete all changes from audit rms coded as

number 9 (since larger rms occasionally acquire these smaller rms). Our results are robust to this

sensitivity analysis.

3. Sample selection and prole

3.1. Sample selection

The initial sample includes all auditor changes reected in the 1993 Standard

and Poors Compustat for the four-year period 19901993. This sample is chosen

to incorporate the eects of the most recent 8-K auditor change disclosure

regulation implemented during 1989 (SEC, 1988). Auditor changes are identied

by the incidence of a change in Compustat auditor code.` Financial institutions

(SICs between 6000 and 6999) are deleted because discretionary accruals estima-

tion is problematic for these rms. In addition, in order to prevent overlapping

periods of analysis, we only include auditor changes preceded by at least two

years with the predecessor auditor. This selection process yields a sample of 514

auditor changes with sucient Compustat data to measure discretionary ac-

cruals in each of the last two years with the predecessor auditor and the rst year

with the successor auditor. Consistent with prior research, we exclude observa-

tions where the absolute value of discretionary accruals exceeds 200% of lagged

assets (DeFond and Park, 1997). This reduces the sample to 503 auditor

changes.

3.2. Descriptive statistics

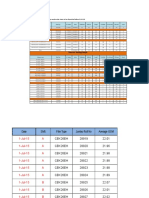

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for our auditor change rms compared

to a benchmark sample drawn from the population of Compustat rms that do

not change auditors. For each auditor change rm we collect Compustat data

for all of the non-change rms with sucient data matched on industry and

year. We then calculate the median value of the descriptive variables from the

distribution of non-change rms and use the resulting distribution of median

values as our benchmark sample.

Table 1 presents mean and median values of the levels and changes in several

nancial variables for both our auditor change rms and for the medians in the

42 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

` The number of observation equals 503 for each year for Sales, Net Income, Total Accruals, Cash

Flows and Total Liabilities. However, due to missing data in Compustat the market-to-book ratio,

Z-score, and Dividends variables contain between 400 and 437 observations each year. The unequal

number of observations across the years aects the additivity of the levels and changes. As

a sensitivity, we replicate the analysis after equalizing the sample across the three years for these

variables (the equalized sample comprises 398, 369 and 403 rms for the market-to-book ratio,

Z-score, and Dividends respectively). The results of this sensitivity are qualitatively similar to that

using the non-equalized sample.

benchmark sample. In addition, we report the mean and median dierences

between the two samples along with their corresponding p-values. Year !2

refers to the penultimate year with the predecessor auditor, year !1 refers to

the last year with the predecessor, and year 0 refers to the rst year with the

successor auditor.`

Several observations can be made from examining Table 1. Three variables

that are commonly used to infer nancial health net income, cash ows and

z-score all indicate that the auditor change rms are in signicantly worse

nancial condition than the industry benchmark sample in each of the three

years examined. However, the extent to which the health of the auditor change

sample deteriorates (or fails to deteriorate) across the three years, varies depend-

ing upon the variable considered. For example, the changes in cash ows in the

auditor change sample are not signicantly dierent than the changes in the

benchmark sample during either of the change periods examined. Thus, the

interpretation of the cash ow variable is that the auditor change rms are in

relatively poor nancial health, but that that they are not getting any worse or

any better across the three years examined. In contrast, the z-score indicates that

the nancial health of the auditor change sample is deteriorating progressively

when compared to the benchmark sample during the three years under analysis.

The change in net income from year !2 to year !1 indicates that auditor

change rms are deteriorating signicantly more rapidly compared to the

benchmark sample, but the change from year !1 to year 0 is insignicantly

dierent across the samples. Because the change in cash ows are not signi-

cantly dierent from the benchmark sample, the signicantly greater decline in

net income must be the result of greater income decreasing accruals. This is

conrmed by looking at the change in total accruals from year !2 to year !1.

Thus, the decline in earnings from year !2 to year !1 is consistent with the

auditor change rms making unusually large negative discretionary and/or

non-discretionary accruals during year !1.

Various other observations may also be made from the data presented in

Table 1. While mean sales among the auditor change rms are generally higher

than among the industry benchmark rms, the medians are not signicantly

dierent. The market-to-book ratio, a measure of growth opportunities (Collins

and Kothari, 1989), is generally no dierent across the two samples over the

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 43

T

a

b

l

e

1

L

e

v

e

l

s

a

n

d

c

h

a

n

g

e

s

i

n

d

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

f

o

r

r

m

s

c

h

a

n

g

i

n

g

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

s

d

u

r

i

n

g

t

h

e

p

e

r

i

o

d

1

9

9

0

1

9

9

3

a

n

d

a

n

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

g

r

o

u

p

Y

e

a

r

r

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

t

o

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

S

a

l

e

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

N

e

t

i

n

c

o

m

e

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

T

o

t

a

l

a

c

c

r

u

a

l

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

C

a

s

h

o

w

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

Y

e

a

r

!

2

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

1

.

1

7

7

1

.

0

5

4

!

0

.

0

6

1

0

.

0

0

7

!

0

.

0

5

1

!

0

.

0

5

8

!

0

.

0

1

0

0

.

0

2

8

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

1

.

0

8

3

1

.

2

3

2

0

.

0

4

0

.

0

3

0

!

0

.

0

4

2

!

0

.

0

3

8

0

.

0

5

9

0

.

0

5

8

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

0

9

5

!

0

.

0

0

2

!

0

.

0

8

5

!

0

.

0

2

1

!

0

.

0

0

9

!

0

.

0

1

0

!

0

.

0

1

6

9

!

0

.

0

1

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

0

1

)

(

0

.

5

3

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

2

0

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

C

h

a

n

g

e

f

r

o

m

!

2

t

o

!

1

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

0

.

0

1

1

0

.

0

0

!

0

.

0

3

2

!

0

.

0

0

6

!

0

.

0

4

1

!

0

.

0

2

0

0

.

0

0

9

0

.

0

0

7

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

!

0

.

0

0

6

!

0

.

0

0

3

!

0

.

0

0

7

!

0

.

0

0

6

!

0

.

0

4

1

!

0

.

0

0

9

0

.

0

0

3

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

0

1

6

!

0

.

0

0

9

!

0

.

0

2

5

!

0

.

0

0

2

!

0

.

0

3

3

!

0

.

0

1

5

0

.

0

0

6

0

.

0

0

2

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

5

3

)

(

0

.

8

5

)

(

0

.

0

7

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

6

7

)

(

0

.

2

2

)

Y

e

a

r

!

1

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

1

.

1

8

8

1

.

0

3

8

!

0

.

0

9

3

!

0

.

0

0

4

!

0

.

0

9

2

!

0

.

0

7

5

!

0

.

0

0

1

0

.

0

4

0

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

1

.

0

7

7

0

.

2

3

2

0

.

0

1

7

0

.

0

2

1

!

0

.

0

5

0

!

0

.

0

4

8

0

.

0

6

2

0

.

0

5

9

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

1

1

1

!

0

.

0

0

9

!

0

.

1

1

0

!

0

.

0

3

0

!

0

.

0

4

2

!

0

.

0

1

6

!

0

.

0

6

3

!

0

.

0

2

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

4

7

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

C

h

a

n

g

e

f

r

o

m

!

1

t

o

0

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

0

.

0

5

6

0

.

0

1

1

!

0

.

0

1

7

!

0

.

0

0

3

!

0

.

0

1

8

!

0

.

0

0

6

0

.

0

0

1

!

0

.

0

0

2

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

!

0

.

0

1

4

!

0

.

0

0

3

!

0

.

0

0

2

!

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

1

!

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

0

7

0

0

.

0

1

9

!

0

.

0

1

5

0

.

0

0

1

!

0

.

0

1

6

!

0

.

0

0

5

!

0

.

0

0

0

!

0

.

0

0

2

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

1

3

)

(

0

.

0

9

)

(

0

.

2

6

)

(

0

.

4

7

)

(

0

.

2

1

)

(

0

.

3

7

)

(

0

.

9

9

)

(

0

.

9

3

)

44 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

Y

e

a

r

0

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

1

.

2

4

4

1

.

0

6

6

!

0

.

1

0

0

0

.

0

0

3

!

0

.

1

1

0

!

0

.

0

7

4

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

4

4

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

1

.

0

6

4

1

.

2

4

2

0

.

0

1

6

0

.

0

2

1

!

0

.

0

5

2

!

0

.

0

5

0

0

.

0

6

3

0

.

0

6

1

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

1

8

0

!

0

.

0

1

3

!

0

.

1

2

5

!

0

.

0

2

1

!

0

.

0

5

8

!

0

.

0

1

9

!

0

.

0

6

3

!

0

.

0

1

8

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

1

6

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

Y

e

a

r

r

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

t

o

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

M

a

r

k

e

t

-

t

o

-

b

o

o

k

r

a

t

i

o

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

T

o

t

a

l

l

i

a

b

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

Z

-

S

c

o

r

e

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

D

i

v

i

d

e

n

d

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

Y

e

a

r

!

2

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

1

.

4

4

7

1

.

2

8

5

0

.

5

6

5

0

.

5

7

4

0

.

9

5

3

1

.

9

4

2

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

1

.

6

4

3

1

.

5

1

8

0

.

5

8

0

2

.

2

9

5

2

.

2

9

5

2

.

5

3

1

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

!

0

.

1

9

6

!

0

.

2

6

0

!

0

.

0

2

7

!

1

.

0

2

4

!

0

.

3

4

2

!

.

3

9

9

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

7

5

)

(

0

.

1

0

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

1

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

C

h

a

n

g

e

f

r

o

m

!

2

t

o

!

1

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

0

.

3

8

4

!

0

.

1

0

4

0

.

0

0

7

0

.

0

0

0

!

0

.

6

0

0

!

0

.

2

2

9

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

0

.

0

1

7

0

.

0

3

3

!

0

.

0

0

6

!

0

.

0

1

0

!

0

.

0

4

2

!

0

.

0

1

8

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

3

7

7

!

0

.

1

0

1

0

.

0

1

4

0

.

0

1

3

!

0

.

5

5

8

!

0

.

1

6

2

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

5

7

)

(

0

.

0

7

)

(

0

.

0

9

)

(

0

.

0

1

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

6

8

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

Y

e

a

r

!

1

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

2

.

3

1

7

1

.

3

4

5

0

.

5

7

2

0

.

5

7

8

0

.

7

3

1

1

.

8

3

1

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

1

.

6

4

8

1

.

5

1

8

0

.

5

8

6

0

.

5

7

2

2

.

2

5

3

2

.

5

3

1

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

6

6

9

!

0

.

2

3

4

!

0

.

0

1

0

!

0

.

0

1

0

!

1

.

5

2

2

!

0

.

4

0

6

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

0

7

)

(

0

.

2

2

)

(

0

.

8

)

(

0

.

2

6

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

1

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 45

T

a

b

l

e

1

(

c

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

Y

e

a

r

r

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

t

o

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

M

a

r

k

e

t

-

t

o

-

b

o

o

k

r

a

t

i

o

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

T

o

t

a

l

l

i

a

b

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

Z

-

S

c

o

r

e

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

D

i

v

i

d

e

n

d

s

/

a

s

s

e

t

s

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

M

e

a

n

M

e

d

i

a

n

C

h

a

n

g

e

f

r

o

m

!

1

t

o

0

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

!

0

.

2

0

0

0

.

0

1

9

0

.

0

1

2

0

.

0

0

0

!

0

.

5

7

3

!

0

.

0

8

5

0

.

0

1

6

0

.

0

0

0

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

0

.

0

5

7

0

.

0

1

2

9

0

.

0

0

4

!

0

.

0

2

3

0

.

0

0

9

0

.

0

2

1

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

!

0

.

2

5

8

!

0

.

0

3

1

0

.

0

0

8

0

.

0

2

2

!

0

.

5

8

2

!

0

.

0

6

8

!

0

.

0

0

1

0

.

0

0

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

5

6

)

(

0

.

8

9

)

(

0

.

4

1

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

0

3

)

(

0

.

5

5

)

(

0

.

9

3

)

Y

e

a

r

0

A

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

2

.

1

6

7

1

.

2

7

9

0

.

5

8

5

0

.

5

9

6

0

.

5

9

1

1

.

8

0

5

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

1

.

6

9

1

1

.

5

9

1

0

.

5

9

0

0

.

5

6

7

2

.

2

6

3

2

.

5

3

1

0

.

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

D

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

0

.

4

7

6

!

0

.

2

9

1

!

0

.

0

1

9

!

1

.

6

7

2

!

1

.

6

7

2

!

0

.

4

1

7

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

0

0

(

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

)

(

0

.

1

7

)

(

0

.

3

6

)

(

0

.

6

7

)

(

0

.

6

8

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

(

0

.

0

5

)

(

0

.

0

0

)

T

h

e

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

c

o

n

s

i

s

t

o

f

a

l

l

r

m

s

t

h

a

t

c

h

a

n

g

e

d

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

s

f

r

o

m

1

9

9

0

t

o

1

9

9

3

w

i

t

h

a

v

a

i

l

a

b

l

e

d

a

t

a

.

T

h

e

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

s

a

m

p

l

e

i

s

c

o

n

s

t

r

u

c

t

e

d

u

s

i

n

g

t

h

e

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

o

f

C

o

m

p

u

s

t

a

t

r

m

s

t

h

a

t

d

o

n

o

t

c

h

a

n

g

e

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

s

o

v

e

r

t

h

e

p

e

r

i

o

d

1

9

9

0

t

o

1

9

9

3

.

F

o

r

e

a

c

h

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

w

e

c

o

l

l

e

c

t

C

o

m

p

u

s

t

a

t

d

a

t

a

f

o

r

a

l

l

o

f

t

h

e

n

o

n

-

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

m

a

t

c

h

e

d

o

n

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

a

n

d

y

e

a

r

.

T

h

e

n

w

e

c

a

l

c

u

l

a

t

e

t

h

e

m

e

d

i

a

n

v

a

l

u

e

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

d

i

s

t

r

i

b

u

t

i

o

n

o

f

n

o

n

-

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

s

f

o

r

e

a

c

h

d

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

v

e

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

a

n

d

u

s

e

t

h

e

r

e

s

u

l

t

i

n

g

d

i

s

t

r

i

b

u

t

i

o

n

o

f

m

e

d

i

a

n

v

a

l

u

e

s

a

s

t

h

e

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

s

a

m

p

l

e

.

T

h

u

s

,

e

a

c

h

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

-

c

h

a

n

g

e

r

m

h

a

s

a

c

o

r

r

e

s

p

o

n

d

i

n

g

m

e

d

i

a

n

i

n

t

h

e

i

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

b

e

n

c

h

m

a

r

k

s

a

m

p

l

e

.

N

e

t

i

n

c

o

m

e

i

s

m

e

a

s

u

r

e

d

b

e

f

o

r

e

e

x

t

r

a

o

r

d

i

n

a

r

y

i

t

e

m

s

.

T

o

t

a

l

a

c

c

r

u

a

l

s

a

r

e

d

e

n

e

d

a

s

n

e

t

i

n

c

o

m

e

b

e

f

o

r

e

e

x

t

r

a

o

r

d

i

n

a

r

y

i

t

e

m

s

m

i

n

u

s

o

p

e

r

a

t

i

n

g

c

a

s

h

o

w

s

.

C

h

a

n

g

e

s

a

r

e

m

e

a

s

u

r

e

d

a

s

t

h

e

r

s

t

d

i

e

r

e

n

c

e

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

p

r

i

o

r

y

e

a

r

l

e

v

e

l

.

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

s

f

o

r

t

h

e

m

e

a

n

s

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

t

w

o

-

t

a

i

l

e

d

t

-

t

e

s

t

s

o

f

t

h

e

n

u

l

l

h

y

p

o

t

h

e

s

i

s

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

m

e

a

n

e

q

u

a

l

s

0

.

p

-

v

a

l

u

e

s

f

o

r

t

h

e

m

e

d

i

a

n

s

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

t

w

o

-

t

a

i

l

e

d

W

i

l

c

o

x

o

n

s

i

g

n

r

a

n

k

t

e

s

t

s

o

f

t

h

e

n

u

l

l

h

y

p

o

t

h

e

s

i

s

t

h

a

t

t

h

e

c

e

n

t

r

a

l

t

e

n

d

e

n

c

y

e

q

u

a

l

s

0

.

Y

e

a

r

!

2

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

t

h

e

p

e

n

u

l

t

i

m

a

t

e

y

e

a

r

w

i

t

h

t

h

e

p

r

e

d

e

c

e

s

s

o

r

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

,

y

e

a

r

!

1

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

t

h

e

l

a

s

t

y

e

a

r

w

i

t

h

t

h

e

p

r

e

d

e

c

e

s

s

o

r

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

a

n

d

y

e

a

r

0

r

e

f

e

r

s

t

o

t

h

e

r

s

t

y

e

a

r

w

i

t

h

t

h

e

s

u

c

c

e

s

s

o

r

a

u

d

i

t

o

r

.

F

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

a

r

e

o

b

t

a

i

n

e

d

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

C

o

m

p

u

s

t

a

t

d

a

t

a

b

a

s

e

,

a

n

d

m

a

r

k

e

t

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

a

r

e

o

b

t

a

i

n

e

d

f

r

o

m

t

h

e

C

R

S

P

d

a

t

a

b

a

s

e

.

T

h

e

n

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

o

b

s

e

r

v

a

t

i

o

n

e

q

u

a

l

s

5

0

3

f

o

r

e

a

c

h

y

e

a

r

f

o

r

S

a

l

e

s

,

N

e

t

i

n

c

o

m

e

,

T

o

t

a

l

a

c

c

r

u

a

l

s

,

C

a

s

h

o

w

s

a

n

d

t

o

t

a

l

l

i

a

b

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

.

D

u

e

t

o

m

i

s

s

i

n

g

d

a

t

a

i

n

C

o

m

p

u

s

t

a

t

a

n

d

C

R

S

P

,

t

h

e

m

a

r

k

e

t

-

t

o

-

b

o

o

k

r

a

t

i

o

,

Z

-

s

c

o

r

e

,

a

n

d

D

i

v

i

d

e

n

d

s

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

c

o

n

t

a

i

n

b

e

t

w

e

e

n

4

0

0

a

n

d

4

3

7

o

b

s

e

r

v

a

t

i

o

n

s

e

a

c

h

y

e

a

r

.

46 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

" One extreme outlier was deleted from the sample analysis of dividends during the last year of the

predecessor and the rst year of the successor auditor.

" Subramanyam (1996) reports that this cross-sectional model is generally better specied than

the time-series model.

period examined. Finally, the analysis of dividends indicates that most of the

auditor change as well as the industry benchmark rms do not pay dividends."

In summary, Table 1 suggests that the auditor change sample is in relatively

poor nancial health. While the analysis of cash ows indicates that the poor

nancial health is relatively constant across the three years examined, the

analysis of z-scores indicates that nancial health is steadily declining over the

period analyzed. And, the analysis of net earnings indicates that there is

a signicant decline in earnings during year !1 that results from unusually

large income decreasing total accruals. This is an important observation given

that the focus of our analysis is discretionary accruals during year !1.

3.3. Estimation of discretionary accruals

We measure discretionary accruals using the cross-sectional variation of the

Jones (1991) model reported in DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994)." This technique

estimates normal accruals as a function of the change in revenues and level of

property, plant and equipment. These variables control for changes in accruals

that are due to changes in the rms economic condition (as opposed to accruals

manipulation). The change in revenue is included because changes in working

capital accounts, part of total accruals, depend on changes in revenue. Property,

plant and equipment is used to control for the portion of total accruals related

to nondiscretionary depreciation expense. The portion of total accruals unex-

plained by normal operating activities is discretionary accruals.

Specically, discretionary accruals are estimated from the following model:

A

GR

/A

GR

"a(1/A

GR

)#b

(RE

GR

/A

GR

)#b

`

(PPE

GR

/A

GR

)#e

GR

(1)

where

A

GR

"total accruals for estimation portfolio rm i for year t;

A

GR

"total assets for estimation portfolio rm i for year t!1;

RE

GR

"change in net revenues for estimation portfolio rm i for year t;

PPE

GR

"gross property plant and equipment for estimation portfolio rm

i for year t and

e

GR

"error term;

This model is separately estimated for every industry (two-digit SIC) and year

combination. Total accruals are measured using Compustat data and dened as

income before extraordinary items minus operating cash ows. Discretionary

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 47

accruals are dened as the error term from the above regression. In our primary

analysis, tests of signicance are computed using both standardized and unstan-

dardized discretionary accruals. Because the results employing standardized

discretionary accruals are similar to those employing unstandardized dis-

cretionary accruals, all subsequent analyses are performed using unstandardized

discretionary accruals. Unstandardized discretionary accruals are used because

they have the appealing property of being interpretable as a proportion of total

assets.

4. Univariate analysis of discretionary accruals

4.1. Univariate analysis without controls

Table 2 presents a univariate analysis of discretionary accruals for the auditor

change rms during the last two years with the predecessor auditor and the rst

year with the successor auditor. Unstandardized and standardized discretionary

accruals scaled by lagged assets are presented in columns (A) and (B), respective-

ly. Mean and median levels and changes in discretionary accruals are presented

for each measure along with p-values for two-tailed tests of signicance. The rst

row reports that the mean and median levels of both unstandardized and

standardized discretionary accruals are insignicantly dierent from zero two

years prior to the auditor change (year !2) for all measures except the

unstandardized mean value, which is marginally negative. However, both

measures become signicantly negative during the last year with the predecessor

auditor (year !1). Both columns also report that the levels of discretionary

accruals in the rst year with the successor auditor (year 0) continue to be

signicantly negative, though smaller in magnitude than the prior year. Thus,

the initial analysis indicates that discretionary accruals are generally insignic-

antly dierent from zero during the penultimate year with the predecessor

auditor but become strongly negative during the last year with the predecessor

auditor. While discretionary accruals continue to be signicantly negative in the

rst year with the successor auditor, their magnitude declines.

4.2. Univariate analysis after controls for nancial performance

Table 1 suggests that our sample rms are in relatively poor nancial health.

If the Jones model does not adequately control for nancial performance, our

estimates of discretionary accruals may be negatively biased (Dechow et al.,

1995). We address this issue by presenting three dierent univariate tests in

Table 3 that attempt to control for the eects of poor performance. First we run

a regression that contains control variables for cash ows and includes the

population of rms that do not change auditors. Next, we perform a matched

48 M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567

Table 2

Discretionary accruals for rms changing auditors during the period 19901993

Year relative to auditor

change

(A) Unstandardized discretionary

accruals

(B) Standardized discretionary

accruals

Mean Median Mean Median

Year !2 !0.021 !0.001 !0.026 !0.004

(p-value) (0.06) (0.86) (0.55) (0.82)

Change from !2 to !1 !0.040 !0.034 !0.151 !0.128

(p-value) (0.01) (0.00) (0.01) (0.00)

Year !1 !0.060 !0.023 !0.188 !0.102

(p-value) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00)

Change from !1 to 0 0.032 0.013 0.038 0.031

(p-value) (0.05) (0.13) (0.53) (0.65)

Year 0 !0.029 !0.012 !0.124 !0.053

(p-value) (0.01) (0.04) (0.01) (0.05)

Discretionary accruals are computed using estimates from the following model for total accruals:

A

GR

/A

GR

"a(1/A

GR

)#b

(RE

GR

/A

GR

)#b

`

PPE

GR

/A

GR

)#e

GR

,

where A

GR

is the total accruals for estimation portfolio rm i for year t; A

GR

is the total assets for

estimation portfolio rm i for year t!1; RE

GR

is the change in net revenues for estimation

portfolio rm i for year t; PPE

GR

is the gross property plant and equipment for estimation portfolio

rm i for year t; and e

GR

is the error term;

Standardized discretionary accruals are computed as

GH

"e

GH

/S(e

GH

),

where s(e

GH

) is the standard deviation of the error term from the model estimated in footnote a.

Parametric signicance tests of the standardized errors are computed as

Z

GH

"

GH

/[(

H

!k)/(

H

!(k#2))]`,

where k is the model degrees of freedom and j is the total number of observations in the matched

portfolio.

The sample consists of 503 rms in columns (A), but the number of observations are slightly lower in

column B because truncated observations dier for the analysis of standardized discretionary

accruals.

p-values for the means are from two-tailed t-tests of the null hypothesis that the mean equals 0.

p-values for the medians are from two-tailed Wilcoxon sign rank tests of the null hypothesis that the

central tendency equals 0. Year !2 refers to the penultimate year with the predecessor auditor, year

!1 refers to the last year with the predecessor auditor and year 0 refers to the rst year with the

successor auditor.

pairs design that controls for cash ows, and third we analyze discretionary

accruals after eliminating observations with extreme values of earnings.

Our rst test attempts to determine whether the discretionary accruals gener-

ated by our sample rms are unusual when compared to the population of

M.L. DeFond, K.R. Subramanyam / Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (1998) 3567 49

The mean (median) dierences in operating cash ows scaled by assets between the match rms

and the treatment rms, for both levels and changes, do not exceed 0.008 (0.0002) for any of the event

years examined.

non-change rms, after orthogonalizing the discretionary accruals to cash ows.

Cash ows are an appealing control variable because they are a commonly used

indicator of nancial health and because Table 1 nds our sample rms exhibit

relatively poor cash ows compared to the population of rms that do not

change auditors. We run an OLS regression that includes both our sample rms

and a control group of 24,841 rm-year observations consisting of all Compus-

tat rms with sucient data that do not change auditors, matched on year and

industry with our auditor change rms. The dependent variable in the regression

is discretionary accruals and the independent variables are the levels of cash

ows, the absolute value of cash ows, and dummies for the auditor change

rms by year. We include the absolute value of cash ows in the analysis because

research has shown that the relation between cash ows and discretionary

accruals is not linear (for example, Dechow et al., 1995, show that discretionary

accruals are biased for extreme values of earnings and cash ows). The dummies

are used to compute discretionary accruals for our auditor change rms that are

orthogonal to cash ows.

The results of this test are presented in column (A) of Table 3 and are

generally consistent with the results before controlling for nancial performance

reported in column (A) of Table 2. Specically, discretionary accruals are