Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Influence of Humanism in Education

Uploaded by

cjhsrisahrlOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Influence of Humanism in Education

Uploaded by

cjhsrisahrlCopyright:

Available Formats

The Influence of Humanism in Education

By Richard Layton

August 1997 In considering the influence of humanism on education I thought it might be useful to go through the Humanist Manifesto II and check all the ideas expressed there which I felt had been taught to me when I attended the public schools in my youth. The exercise turned out to be a very pleasant surprise to me. I had expected to check only six, eight, or perhaps 12 at the most; but when I had finished, I found that I had checked no less than 58 ideas. I had not fully appreciated just how much humanism had influenced modern education until I did this exercise. I would like to mention to you just nine of the ideas I checked--every sixth one in the list. They are: 1. that clear-minded men and women are able to marshal the will, intelligence, and cooperative skills for shaping a desirable future 2. that people should work for self-actualization and the rectification of social injustices 3. that, even as science pushes back the boundary of the known, man's sense of wonder is continually renewed, and art, poetry, and music find their places, along with religion and ethics 4. that it is desirable to safeguard, extend, and implement principles of human freedom 5. that the conditions of work, education, devotion, and play should be humanized 6. that equality of opportunity and recognition of talent and merit are desirable 7. that the schools should foster satisfying and productive living 8. that ecological damage and resource depletion must be checked 9. that we must work together for a humane world by means commensurate with humane ends. Those of you who attended private schools while growing up may find that a good many humanist principles are being taught there, too, although the number of them may vary according to the prevailing philosophy of education of the school. The same could be said of public schools. How did it come about that the humanistic approach is so prominent in today's schools in contrast to the situation that existed in education throughout most of civilized human history. To find the answer we must look at history. Actually some elements of humanism were present even in the schools of early civilization, but the emphasis in those schools was not humanistic. The oldest known systems of education in history had two characteristics in common: they taught religion, and they promoted the traditions of the people. That is to say, they taught students to think and act the same as their ancestors had thought and acted. This contrasted with the humanistic orientation, which teaches people to engage in the search for truth and for solutions to problems open-mindedly with a sense of human caring by employing critical intelligence and the controlled use of scientific methods.

However, some humanistic elements that were present in the schools of ancient civilizations were the teachings in Egypt of the sciences, mathematics, and architecture; in China the philosophies of Confucius, Lao-tzu and others; and in Greece gymnastics, mathematics, music, philosophy, and the aesthetic ideal. The educational systems in Western countries came to be based on the religious tradition of the Jews, both in the religious form and in the version modified by Christianity. A second tradition was derived from education in ancient Greece, where Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, were the influential thinkers on education. Jewish-Christian influence was a very unfortunate occurrence for the Western world, leading to that great period of institutionalized ignorance known as the Middle Ages, the first part of which is often referred to as the Dark Ages. Humanism fared badly during the Middle Ages, as superstition, faith in authoritarian, dogmatic religion, and subservience to religious and feudal authority took over. Superstition imposingly invaded the teaching and the practice of medicine, sometimes to the harm of people. "Mules fared better than men," according to historian Will Durant. As this era ended, the poet and scholar Petrarch was probably the first to conceive of the thousand years from late Roman antiquity down to and including his own day as an age of darkness, marked by the extinction of excellence in both literary culture and public virtue. Then in the fourteenth century a revival of culture took place which was aroused by the rediscovery of the ancient Greek and Roman cultures. Latin and Greek classics were found lying neglected in monastic or cathedral libraries, rotting in dust, or mutilated to make Psalters or amulets, in foul dark dungeons, old chests, and even tombs. The rediscoverers came to be called the humanists because they occupied themselves with the humanities, that is, with writings that were more human. "The humanists captivated the mind of Italy," and later Europe, "turned it from religion to philosophy, from heaven to earth, and revealed to an astonished generation the riches of pagan thought and art," says historian Will Durant. "The proper study of mankind was now to be man, in all the potential strength and beauty of his body, in all the joy and pain of his senses and feelings, in all the frail majesty of his reason; and in these as most abundantly and perfectly revealed in the literature and art of ancient Greece and Rome. This was humanism." The humanist-inspired revival, known as the Renaissance, following the example of ancient Greece, also led to a renewal of interest in science. Witness the wondrous changes that have taken place in human society in the 600 years since then that have been made possible by scientific research. The masses of the people in large areas of the earth now enjoy a standard of living far higher than in any previous centuries in all human history. This has come about by the development of an advanced technology that would not have been possible without the discoveries of scientific research. Although many people still live in poverty, progress has been made against it among hundreds of millions, perhaps even billions, of people. The masses of Asia have been saved from starvation by the scientific development of a new strain of rice, which produces four times as great a yield per acre as strains being raised a few decades ago. The huge populations of China and India have experienced improvements in their economies and in the standards of living for many of their people in recent decades. And the idea of education for the masses has taken hold all over the world.

The humanists had the important and original conception that education was neither completed at school nor limited to the years of one's youth, but that it was a continuous process making use of varied instruments. Companionship, games, and pleasure were part of education. They sought a new historical consciousness. They reconstructed the past in order better to understand themselves and their own time. Their movement was going to have a profound influence on education in later centuries. And yet, despite their emphasis on the human, they had no interest in extending education to the masses, but turned their attention to the sons of princes and rich burghers. The masses were to remain steeped in poverty and superstition, untouched by the beauty and excitement of the humanist world view for another century. Possibly the educational reform that has most influenced our culture toward the acceptance of humanistic values has been the establishment of universal education for all the people. Interestingly, the first popular movement toward public education for the masses since the days of the early Roman Republic was by a man who was at odds with the humanists, especially with the prominent humanist scholar Erasmus, who wanted to encourage education for a small group of writers and scholars only. The man was Martin Luther, who wanted to open up education to the sons of peasants and miners, for they had contributed to the success of his religious reforms in the Protestant movement. He favored limited democratic reforms which would open up schools for just a few hours a week to all, both boys and girls, regardless of their financial situation. Humanistic schools open to the public were established in Germany soon afterward. Phillip Melanchthon, moving away from Luther's interest in combining education with religious reform, set up a new educational system, particularly a secondary school system. On the other hand, perhaps the most original contribution of the Reformation was the extension of education at the elementary level. Elementary education for the middle classes developed in the 17th and 18th centuries, and more and more the state saw as its task the responsibility for establishing and maintaining schools. The 18th century was a special landmark in the development of education. In contrast to the religious and rationalistic orientation of schools in the 17th century, the ideal in the 18th century that prevailed more and more was the development of the secular, pragmatic gentleman. Sir Francis Bacon advocated the use of inductive and empirical methods in the schools, which he thought would strengthen humans and make possible a reorganization of society. Philosopher Rene Descartes encouraged the development of critical rationality and the teaching of any practical discipline that makes man a master and lord of nature. An important new outlook of this age was the notion that education is guaranteed, not by limitless widening and assimilation of facts, but rather by the mastery of thinking and judgmental categories. In America, the Puritans established what was probably the first school in the colonies in Boston in 1635. It was a far cry from a humanistic one. Its charges were instructed in reading, religion, and the colony's principal laws. Puritanism was the established religion. Rejecting democracy and toleration as unscriptural, the Puritans put their trust in a theocracy of the elect that brooked no divergence from Puritan orthodoxy. So close was the relation between state and church that an offense against the one was an offense against the other and, in either case, "treason to the Lord Jesus." The young, like the old, were sinners doomed by almost insuperable odds to perdition. Not even infants were spared. To God, indeed, they were depraved, unregenerate, and

damned. Hence, the sooner the young learned the ground rules of the good society, as revealed in the Bible, the better. When Thomas Jefferson died in 1826, the nation stood on the threshold of a tremendous transformation. During the ensuing quarter century it expanded enormously in space and population. Old cities grew larger and new ones more numerous. The era saw the coming of the steamboat and the railroad. Commerce flourished, and so did agriculture. The age witnessed the rise of the common man with the right to vote and hold office. It was a time of overflowing optimism, of dreams of perpetual progress, moral uplift, and social betterment. Such was the climate that engendered the common school. Open freely to every child and upheld by public funds, it was to be a lay institution under the sovereignty of the state, the archfather, in short, of the present-day public school. In 1837, Massachusetts established the first state board of education. Its first secretary, Horace Mann, campaigned tirelessly throughout the state, often against bitter opposition, for more support for public schools and achieved success that was to start a massive movement for publicly financed common schools throughout the United States. The soil that rooted the common school became the seedbed for the high school, which also became prevalent by the next century. Now all states have mandatory attendance for all youngsters up to the age of 16 or 18. Three-fourths of all teenagers graduate from high school. Universal public education has spread throughout many parts of the world, and it has been perhaps the greatest educational development since the beginning of civilization! The man who has had the most influence on the course of education in America in the 20th century is the educator, philosopher, social critic, and psychologist, John Dewey, who died in 1952. A humanist and an instrumentalist, he was considered the premier philosopher of his time. Dewey was critical of the excessively rigid and formal approach to education that dominated the practice of most American schools in the latter part of the 19th century. He argued that that approach was based upon a faulty psychology in which the child was thought of as a passive creature upon whom information and knowledge had to be imposed. But Dewey was equally critical of the "new education," which was based on a sentimental idealization of the child. This child-oriented approach advocated that the child himself should pick and choose what he wanted to study. It also was based on mistaken psychology, which neglected the immaturity of the child's experience. Education is, or ought to be, said Dewey, a continuous reconstruction of experience in which there is a development of immature experience toward experience funded with the skills and habits of intelligence. The slogan "Learn by Doing" was not intended as a credo for anti-intellectualism but, on the contrary, was meant to call attention to the fact that the child is naturally an active, curious, and exploring creature. A properly designed education must be sensitive to this active dimension of life and must guide the child, so that through his participation in different types of experience his creativity and autonomy will be cultivated rather than stifled. The child is not completely malleable, nor is his natural endowment completely fixed and determinate. Like Aristotle, Dewey believed that the function of education is to encourage those habits and dispositions that constitute intelligence. Dewey placed great stress on creating the proper type of environmental conditions for eliciting and nurturing these habits. His conception

of the educational process is therefore closely tied to the prominent role that he assigned to habit in human life. Education as the continuous reconstruction and growth of experience also develops the moral character of the child. Virtue is taught not by imposing values upon the child but by cultivating fair-mindedness, objectivity, imagination, openness to new experiences, and the courage to change one's mind in the light of further experience. Dewey also thought of the school as a miniature society; it should not simply mirror the larger society but should be representative of the essential institutions of this society. The school as an ideal society is the chief means for social reform. In this controlled social environment of the school it is possible to encourage the development of creative individuals, who will be able to work effectively to eliminate existing evils and institute reasonable goods. The school, therefore, is the medium for developing the set of habits required for systematic and open inquiry and for reconstituting experience that is funded with greater harmony and aesthetic quality. Dewey perceived acutely the threat posed by unplanned technological, economic, and political development to the future of democracy. The natural direction of these forces is to increase human alienation and to undermine the shared experience that is so vital for the democratic community. For this reason, Dewey placed much importance on the function of the school in the democratic community. The school is the most important medium for strengthening and developing a genuine democratic community, and the task of democracy is forever the creation of a freer and more humane experience in which all share and participate. We have come a long way since the days of early civilizations in creating schools that contribute meaningfully to the self-actualization of the individual and the society. But in spite of this encouraging progress, it is all too obvious that powerful influences are still at work in our society today, as they have been in all societies throughout history, that would thwart education for humanistic self-actualization and superimpose on us an authoritarian, dogmatic, superstitious approach to life. Will Durant has commented, " The historian acquainted with the pervasive pertinacity of nonsense reconciles himself to a glorious future for superstition; he does not expect perfect states to arise out of imperfect men; he perceives that only a small proportion of any generation can be so freed from economic harassment as to have leisure and energy to think their own thoughts instead of those of their forebears or their environment; and he learns to rejoice if he can find in each period a few men and women who have lifted themselves, by the bootstraps of their brains, or by some boon of birth or circumstance, out of superstition, occultism, and credulity to an informed and friendly intelligence conscious of its infinite ignorance."

You might also like

- Humanism in Education FDocument25 pagesHumanism in Education FV.K. Maheshwari89% (9)

- The Philosophical Movements in EducationDocument59 pagesThe Philosophical Movements in EducationCaren Gay Gonzales Taluban80% (5)

- Socialism in Philosophy of EducationDocument5 pagesSocialism in Philosophy of EducationKlitz Nadon100% (2)

- Existentialism in EducationDocument7 pagesExistentialism in EducationDaniela Marie SalienteNo ratings yet

- Four General or World PhilosophiesDocument5 pagesFour General or World PhilosophiesMichelle Ignacio - DivinoNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper 4 - NaturalismDocument1 pageReaction Paper 4 - NaturalismDarwin Dionisio ClementeNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument23 pagesPhilosophy of EducationJerome BagsacNo ratings yet

- EDFD201 Reaction Paper: Psycho-Philosophical Foundations of Education Final PaperDocument13 pagesEDFD201 Reaction Paper: Psycho-Philosophical Foundations of Education Final PaperEdel Ramilo80% (10)

- Foundations of Education PDFDocument65 pagesFoundations of Education PDFMkesvillon Dhark60% (5)

- Reaction Paper 7 - PerennialismDocument1 pageReaction Paper 7 - PerennialismDarwin Dionisio ClementeNo ratings yet

- Scholasticism and Monasticism.Document19 pagesScholasticism and Monasticism.annexiety14100% (9)

- Realism in EducationDocument24 pagesRealism in Educationjnsengupta100% (3)

- The Psychological Tendency in EducationDocument3 pagesThe Psychological Tendency in EducationEmerson67% (3)

- Assumption College Philosophy of Education Graduate ProgramsDocument3 pagesAssumption College Philosophy of Education Graduate ProgramsJemuel Luminarias100% (2)

- Educational System in Pre-Spanish PhilippinesDocument5 pagesEducational System in Pre-Spanish PhilippinesMeanne Winx50% (4)

- Comparative Philosophy of EducationDocument4 pagesComparative Philosophy of EducationNick Penaverde25% (4)

- Medieval Philosophy of EducationDocument25 pagesMedieval Philosophy of EducationMarnelle Tero100% (1)

- Social Traditionalism Social Experimentalism: Who Were The Teachers? Why Did They Teach?Document5 pagesSocial Traditionalism Social Experimentalism: Who Were The Teachers? Why Did They Teach?HyacinthLoberizaGalleneroNo ratings yet

- Foundation of Education Catholic Counter Reformation Kerth M. GalagpatDocument12 pagesFoundation of Education Catholic Counter Reformation Kerth M. GalagpatKerth GalagpatNo ratings yet

- 4 Theistic Realism and EducationDocument4 pages4 Theistic Realism and EducationCherrieFatima0% (1)

- Chapter 3 MOVEMENTS THAT HELPED SHAPE MODERN EDUCATIONAL THOUGHTS AND IDEALSDocument15 pagesChapter 3 MOVEMENTS THAT HELPED SHAPE MODERN EDUCATIONAL THOUGHTS AND IDEALSMark Palon Ylanan81% (16)

- Shaping Paper EnglishDocument26 pagesShaping Paper EnglishCharity S. Jaya - AgbonNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument67 pagesPhilosophy of EducationDharyl Gomez Ballarta100% (1)

- Statistical Requirements Mof Educational Plans 2.0Document18 pagesStatistical Requirements Mof Educational Plans 2.0rezhabloNo ratings yet

- Essentialism & PerennialismDocument7 pagesEssentialism & PerennialismDihays Damha100% (2)

- Logical PositivismDocument3 pagesLogical PositivismAiza Jamito100% (1)

- Philosophical Bases of Curriculum and Curriculum DevelopmentDocument13 pagesPhilosophical Bases of Curriculum and Curriculum Developmentkate cacay100% (4)

- Education System of IndonesiaDocument21 pagesEducation System of IndonesialorraineNo ratings yet

- Explicit TeachingDocument8 pagesExplicit TeachingCrisanta Dicman UedaNo ratings yet

- Five Educational PhilosophiesDocument23 pagesFive Educational PhilosophiesLori Brown0% (1)

- Verbal RealismDocument16 pagesVerbal RealismGenesis Aguilar100% (2)

- K To 12 Features PDFDocument59 pagesK To 12 Features PDFszhych mangarinNo ratings yet

- Learning Strategies of Indigenous Peoples Students of Philippine Normal University: Basis For A Proposed Pedagogical ModelDocument11 pagesLearning Strategies of Indigenous Peoples Students of Philippine Normal University: Basis For A Proposed Pedagogical ModelMax ZinNo ratings yet

- Nature of Truth DiscussedDocument1 pageNature of Truth DiscussedMD MC Detlef100% (2)

- What Is PerennialismDocument2 pagesWhat Is PerennialismKristin Lee100% (3)

- Scheffler's Four Models of EducationDocument10 pagesScheffler's Four Models of EducationSini WosNo ratings yet

- Piaget's Theory of Cognitive DevelopmentDocument3 pagesPiaget's Theory of Cognitive Developmentjestony matillaNo ratings yet

- Nature Scope of Philosophy of EducationDocument26 pagesNature Scope of Philosophy of Educationkristinejoy barutNo ratings yet

- CODE SWITCHING (Concept Paper) .Document9 pagesCODE SWITCHING (Concept Paper) .Regina100% (1)

- Report FS 101 Advanced Foundation of EducationDocument21 pagesReport FS 101 Advanced Foundation of EducationJulie Anne Valdoz Casa67% (3)

- Research-Based Teaching and Student-Centered LearningDocument2 pagesResearch-Based Teaching and Student-Centered LearningNova VillonesNo ratings yet

- The 1987 Constitution (Article Xiv) The Legal Bases of The Philippine Education SystemDocument4 pagesThe 1987 Constitution (Article Xiv) The Legal Bases of The Philippine Education SystemJerome Varquez0% (1)

- EDUC204 Reflection Paper 01Document2 pagesEDUC204 Reflection Paper 01azeNo ratings yet

- Coloma Ethel Gillian, Mercado Jhiemer, Napat Yra Mariz, Pastor, Patricia LaineDocument15 pagesColoma Ethel Gillian, Mercado Jhiemer, Napat Yra Mariz, Pastor, Patricia LaineKristela Mae ColomaNo ratings yet

- NaturalismDocument20 pagesNaturalismLalit Joshi92% (12)

- PU Philosophy of Multicultural EducationDocument40 pagesPU Philosophy of Multicultural Educationcluadine dinerosNo ratings yet

- Importance of Philosophy in EducationDocument24 pagesImportance of Philosophy in EducationWensore Cambia50% (6)

- Education As A Social ProcessDocument5 pagesEducation As A Social Processmrm MNo ratings yet

- Reflection On Idealism and Realism in EducationDocument2 pagesReflection On Idealism and Realism in EducationDiana Llera Marcelo100% (1)

- The Philippine Educational System in Relation To John Dewey's Philosophy of EducationDocument18 pagesThe Philippine Educational System in Relation To John Dewey's Philosophy of EducationJude Boc Cañete100% (1)

- Essay On Perennialist Educational PhilosophyDocument8 pagesEssay On Perennialist Educational Philosophytdedeaux725100% (1)

- Modern Philosophers and their Contributions to EducationDocument3 pagesModern Philosophers and their Contributions to EducationRaquisa Joy Linaga100% (1)

- Nature of Educational PhilosophyDocument4 pagesNature of Educational Philosophyjing care67% (18)

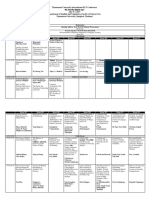

- Hinandayan National High School: Table of Specification (Tos) in Grade 7 - EnglishDocument2 pagesHinandayan National High School: Table of Specification (Tos) in Grade 7 - EnglishZhan DuhacNo ratings yet

- Solving Issues in an English Language Program for Saharan StudentsDocument5 pagesSolving Issues in an English Language Program for Saharan StudentsNorkhan Macapanton50% (2)

- Integrated Teaching MethodsDocument3 pagesIntegrated Teaching MethodsAsha jilu100% (1)

- Implementing MTB-MLE: Successes, Challenges & SolutionsDocument8 pagesImplementing MTB-MLE: Successes, Challenges & Solutionsere chanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Factors and Movements That Have Influenced The Development of Western EducationDocument4 pagesLesson 3 Factors and Movements That Have Influenced The Development of Western EducationkiokocurtisNo ratings yet

- "O ::'.::,"J"::::,Il" : I Es-331: Gurrtculum and TnsrrucnonDocument8 pages"O ::'.::,"J"::::,Il" : I Es-331: Gurrtculum and TnsrrucnonacsrivastavNo ratings yet

- Staff Selection Commission Exams 2010Document104 pagesStaff Selection Commission Exams 2010rmurali179No ratings yet

- E-Portfolio As A Higher Training Professional Tool, A Comparative-Descriptive StudyDocument9 pagesE-Portfolio As A Higher Training Professional Tool, A Comparative-Descriptive StudyLidiaMaciasNo ratings yet

- PDF 20220813 223909 0000Document12 pagesPDF 20220813 223909 0000ronan razaNo ratings yet

- How To Be A High School SuperstarDocument5 pagesHow To Be A High School Superstarsparklefrog67% (3)

- Competencies AssessmentDocument5 pagesCompetencies Assessmentapi-280076543No ratings yet

- Look and Read. Check or Put An .: ChairDocument3 pagesLook and Read. Check or Put An .: ChairMaria GomezNo ratings yet

- John Holmwood - Functionalism & Its Critics PDFDocument8 pagesJohn Holmwood - Functionalism & Its Critics PDFFrancoes MitterNo ratings yet

- Science Lesson Plan Soil SamplesDocument4 pagesScience Lesson Plan Soil SamplesColleenNo ratings yet

- TOEIC LISTENING COURSEDocument2 pagesTOEIC LISTENING COURSEPriyaNo ratings yet

- Something DifferentDocument50 pagesSomething DifferentThe GrowerNo ratings yet

- Archie Resume 2019Document4 pagesArchie Resume 2019Archie Gene GallardoNo ratings yet

- Tu Elt Conference Program 2017 May 15Document3 pagesTu Elt Conference Program 2017 May 15api-285624898No ratings yet

- National Service Training Program 1Document9 pagesNational Service Training Program 1Jerome DiassanNo ratings yet

- Anthropology Unit PlanDocument7 pagesAnthropology Unit Planapi-392230729100% (1)

- Questionnaire Life Long Learners With 21ST Century SkillsDocument3 pagesQuestionnaire Life Long Learners With 21ST Century SkillsHenry BuemioNo ratings yet

- EE287Document3 pagesEE287ShanmuganathanTrNo ratings yet

- Trainers GuideDocument116 pagesTrainers GuideNaseem Qazi100% (1)

- General Methods of Teaching (EDU 301) : Unit SubjectDocument90 pagesGeneral Methods of Teaching (EDU 301) : Unit SubjectvothanhvNo ratings yet

- Caroline Larson Fundraising Portfolio After School MattersDocument16 pagesCaroline Larson Fundraising Portfolio After School Mattersapi-442798698No ratings yet

- Physical Education and Health in an Activity- and Child-Centered CurriculumDocument18 pagesPhysical Education and Health in an Activity- and Child-Centered CurriculumLynne Valdes50% (2)

- School Readiness Validation for SY 2022-2023Document10 pagesSchool Readiness Validation for SY 2022-2023Glance MacateNo ratings yet

- Banasthali Broucher PDFDocument11 pagesBanasthali Broucher PDFsanjayNo ratings yet

- RFL Profile of BODDocument2 pagesRFL Profile of BODabdul ohabNo ratings yet

- Social Winter Project Report FinalDocument32 pagesSocial Winter Project Report Finalsiddeshsai54458No ratings yet

- Teaching Methodology and Lesson PlanningDocument4 pagesTeaching Methodology and Lesson PlanningRosalina RodríguezNo ratings yet

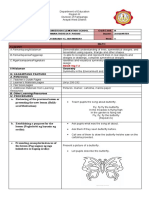

- 3rd COT SymmetryDocument5 pages3rd COT SymmetryMARIA CRISTINA L.UMALI100% (5)

- Basu Colonial Educational Policies Comparative ApproachDocument12 pagesBasu Colonial Educational Policies Comparative ApproachKrati SinghNo ratings yet

- Understanding Radicals and Variations in MathDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Radicals and Variations in MathMarlaFirmalino100% (1)

- Brian Croxall CV, 5 September 2023Document18 pagesBrian Croxall CV, 5 September 2023Brian CroxallNo ratings yet