Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taxation and Equal Protection

Uploaded by

Sansui Jusan RochelOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taxation and Equal Protection

Uploaded by

Sansui Jusan RochelCopyright:

Available Formats

Taxation and Equal Protection

Both the United States and Minnesota Constitutions prohibit the legislature and state government th generally from denying persons the equal protection of the law. The 14 amendment of the United States Constitution provides: No state shall * * * deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Art. XIV, 1. The Minnesota Constitution contains both a general equal protection clause and a clause requiring uniformity of taxation. Minn. Const. art. I, 2 (general); art. X, 1 (uniformity clause). Most tax laws are subject to rational basis review under the Equal Protection Clause; to be constitutional they must simply have a rational relationship to a legitimate legislative purpose. The Equal Protection Clause was initially adopted primarily to limit or prohibit racial discrimination by the states. The courts have also applied it to proscribe other forms of invidious discrimination (e.g., based on religion, ethnicity, etc.). However, legislation often necessarily involves discrimination in the broader sense that groups of individuals or businesses are treated differently based on particular characteristics (e.g., amounts of income, type of business, uses of property, etc.) that in the abstract are unobjectionable. The clause was not intended to restrict legislation that imposed different tax or regulatory rules, for example, on retailers than on manufacturers. Thus, the U.S. Supreme Court has developed a stricter standard of review for laws that create suspect classifications or deprive someone of a fundamental right as a compared with more benign legislative classifications. The lines between the two categories (perhaps inevitably) blur at the edges. At times the Court has explicitly talked about a middle level of review. y Strict scrutiny applies to suspect classifications (such as race or religion) or to denial of fundamental rights (such as the right to vote). The classification is constitutional only if there is a compelling reason for using the classification. If strict scrutiny applies, in most circumstances the classification will be unconstitutional. A rational basis test applies to economic regulation not involving suspect classifications and, thus, to most of the classifications involved in the tax laws. In general, a classification has a rational basis and is constitutional, if it reasonably related to or has some rational relationship to the objective the legislature sought to achieve. The rational basis test gives the legislature considerable flexibility in creating classifications.

Very few tax statutes have been struck down under the Equal Protection Clause. The U.S. Supreme Court has generally given states wide latitude to fashion tax classifications, perhaps more than in any other area of law. See San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriquez, 411 U.S. 1, 41 (1973), where the Court noted: [T]hat in taxation, even more than in other fields, legislatures possess the greatest freedom in classification. Nevertheless, the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down a number of state tax statutes on equal protection grounds. Many (probably most) of these statutes have involved laws that discriminated against nonresidents or out-of-state businesses. Some examples include: y y Imposing a higher state insurance premium tax on out-of-state insurance companies, Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. v. Ward, 470 U.S. 869 (1985); Paying rebates to residents, graduated based on how many years they had lived in-state, Zobel v. Williams, 457 U.S. 55 (1982);

Local assessment practice that raised tax valuations to the amount of the sales price but otherwise assessed properties at a fraction of market value, Allegheny Pittsburgh Coal Co v. County Commission of Webster County, 488 U.S. 336 (1989). Compare Nordlinger v. Hahn, 505 U.S. 1 (1992) (statute that applied a similar rule did not violate equal protection).

The Minnesota Supreme Court has held that the Uniformity Clause of the Minnesota Constitution is no more restrictive than the Equal Protection Clause. Although the Minnesota Constitution contains a specific clause that requires taxes to be uniform upon the same class of subject[,] the Minnesota courts have held repeatedly that this clause is no more restrictive than the Equal Protection Clause. Reed v. Bjornson, 253 N.W.2d 102, 105 (upholding the graduated individual income tax) appears to be the first case to establish this rule. The meaning of the Uniformity Clause remains a matter of state law and, thus, a change in the interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause by the U.S. Supreme Court should not be thought to automatically change the meaning of the Uniformity Clause. However, the Minnesota courts have fairly consistently followed federal interpretations of the Equal Protection Clause, since Reed v. Bjornson. The Minnesota Supreme Court has set out a three-part test to determine if a tax classification satisfies the Uniformity Clause. Miller Brewing Co. v. State, 284 N.W.2d 353, 356 (1979). Under this test, the classification must: y y y Not be manifestly arbitrary or fanciful but must be genuine and substantial; Be genuine or relevant to the purpose of the law; and The purpose of the statute must be one that the state can legitimately attempt to achieve.

The Minnesota courts have generally been very deferential to legislative tax classifications. In fact, the Minnesota Supreme Court has not struck down a tax statute for violating the Uniformity Clause in the last two decades. Some examples of laws upheld include: y y The limited market value law that taxes otherwise identical properties at different rates based upon how rapidly their values are increasing, Matter of McCannel, 301 N.W.2d 190 (Minn. 1980); Combined gross receipts gambling tax that imposes a higher tax rate on organizations with more total gross receipts from gambling activities, Brainerd Area Civic Center v. Commissioner of Revenue, 499 N.W.2d 468 (Minn. 1993); Contamination tax imposing higher property tax rates on polluted property, depending upon whether the owner was a responsible party and whether the owner had entered a response plan, Westling v. County of Mille Lacs, 518 N.W.2d 815 (Minn. 1998).

You might also like

- Ouse Esearch: Short SubjectsDocument2 pagesOuse Esearch: Short SubjectsJembrain CanubasNo ratings yet

- Austin v. New Hampshire, 420 U.S. 656 (1975)Document11 pagesAustin v. New Hampshire, 420 U.S. 656 (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Constitution and the Development of US Business, 1877--1914From EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Constitution and the Development of US Business, 1877--1914No ratings yet

- Fitzgerald v. Racing Assn. of Central Iowa, 539 U.S. 103 (2003)Document7 pagesFitzgerald v. Racing Assn. of Central Iowa, 539 U.S. 103 (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemFrom EverandThe Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemNo ratings yet

- Wayfair Ruling Undermines Nicastro Personal Jurisdiction StandardDocument20 pagesWayfair Ruling Undermines Nicastro Personal Jurisdiction StandardJOHAN GABRIEL FABIANo ratings yet

- Introduction to US Legal Systems in 40 CharactersDocument7 pagesIntroduction to US Legal Systems in 40 CharactersJenyfer BarriosNo ratings yet

- Massachusetts Nurses Association v. Michael S. Dukakis, 726 F.2d 41, 1st Cir. (1984)Document9 pagesMassachusetts Nurses Association v. Michael S. Dukakis, 726 F.2d 41, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tigner v. Texas, 310 U.S. 141 (1940)Document6 pagesTigner v. Texas, 310 U.S. 141 (1940)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Code Breaker; The § 83 Equation: The Tax Code’s Forgotten ParagraphFrom EverandCode Breaker; The § 83 Equation: The Tax Code’s Forgotten ParagraphRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- 20 Page Report On Liability PDFDocument27 pages20 Page Report On Liability PDFMike K100% (1)

- Federal "Unemption" of State Antitrust EnforcementDocument15 pagesFederal "Unemption" of State Antitrust EnforcementjayhimesNo ratings yet

- Lehnhausen v. Lake Shore Auto Parts Co., 410 U.S. 356 (1973)Document8 pagesLehnhausen v. Lake Shore Auto Parts Co., 410 U.S. 356 (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hamilton's Economic Policies: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemFrom EverandHamilton's Economic Policies: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemNo ratings yet

- Ante, at 28. and "A Vegetable-Purchase Mandate" (Or ADocument11 pagesAnte, at 28. and "A Vegetable-Purchase Mandate" (Or ADavid GunnellsNo ratings yet

- Can Tort Reform and Federalism Coexist?, Cato Policy Analysis No. 514Document31 pagesCan Tort Reform and Federalism Coexist?, Cato Policy Analysis No. 514Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- The Dirty Dozen: How Twelve Supreme Court Cases Radically Expanded Government and Eroded FreedomFrom EverandThe Dirty Dozen: How Twelve Supreme Court Cases Radically Expanded Government and Eroded FreedomNo ratings yet

- Kittery Motorcycle v. Rowe, 1st Cir. (2003)Document12 pagesKittery Motorcycle v. Rowe, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 1 Commerce Clause: 1.1 Relevant Constitutional Text (Article, Amendment, Section )Document4 pages1 Commerce Clause: 1.1 Relevant Constitutional Text (Article, Amendment, Section )Bobby LewisNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionNo ratings yet

- King v. BurwellDocument47 pagesKing v. BurwellPaigeLavenderNo ratings yet

- The Constitutional Case for Religious Exemptions from Federal Vaccine MandatesFrom EverandThe Constitutional Case for Religious Exemptions from Federal Vaccine MandatesNo ratings yet

- Arkansas v. Farm Credit Servs. of Central Ark., 520 U.S. 821 (1997)Document9 pagesArkansas v. Farm Credit Servs. of Central Ark., 520 U.S. 821 (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument26 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Freeman v. Hewit, 329 U.S. 249 (1947)Document29 pagesFreeman v. Hewit, 329 U.S. 249 (1947)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Dysfunction on Trial: Congressional Lawsuits and the Separation of PowersFrom EverandConstitutional Dysfunction on Trial: Congressional Lawsuits and the Separation of PowersNo ratings yet

- Sison v. Ancheta, 130 SCRA 654: SyllabusDocument6 pagesSison v. Ancheta, 130 SCRA 654: SyllabusAname BarredoNo ratings yet

- Motion To Dismiss Shane CoxDocument11 pagesMotion To Dismiss Shane CoxThe Daily HazeNo ratings yet

- "Robert's Tax" (TM) BCDocument5 pages"Robert's Tax" (TM) BCapi-127658921No ratings yet

- Kittery Motorcycle v. Rowe, 320 F.3d 42, 1st Cir. (2003)Document11 pagesKittery Motorcycle v. Rowe, 320 F.3d 42, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Last Rights: The Fight to Save the 7th AmendmentFrom EverandLast Rights: The Fight to Save the 7th AmendmentNo ratings yet

- Cincinnati Soap Co. v. United States, 301 U.S. 308 (1937)Document10 pagesCincinnati Soap Co. v. United States, 301 U.S. 308 (1937)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Collins Holding Corp v. Jasper County SC, 4th Cir. (1997)Document7 pagesCollins Holding Corp v. Jasper County SC, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Samuel Fiore, 434 F.2d 966, 1st Cir. (1970)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Samuel Fiore, 434 F.2d 966, 1st Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Defending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideFrom EverandDefending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideNo ratings yet

- Scotus OpinionDocument193 pagesScotus OpinionNational Journal100% (1)

- American Goods: A Collection of Essays on Law, Economics, Sports, Nostalgia, and Public InterestFrom EverandAmerican Goods: A Collection of Essays on Law, Economics, Sports, Nostalgia, and Public InterestNo ratings yet

- National Federation of Independent Business v. SebeliusDocument193 pagesNational Federation of Independent Business v. SebeliusCasey SeilerNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court rules on illegal arrest, search and seizureDocument3 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court rules on illegal arrest, search and seizureReth Guevarra100% (1)

- Course Curriculum for Public Relations & Corporate ImageDocument4 pagesCourse Curriculum for Public Relations & Corporate ImageAayush NamanNo ratings yet

- Non Institutional CorrectionDocument16 pagesNon Institutional CorrectionCristina Joy Vicente Cruz100% (5)

- A Legal Analysis of The Role of Bar Associations Towards Access To Justice For The Poor: A Case Study of CameroonDocument10 pagesA Legal Analysis of The Role of Bar Associations Towards Access To Justice For The Poor: A Case Study of CameroonEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume II of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesFrom EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume II of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesNo ratings yet

- IT Act 2000Document8 pagesIT Act 2000Mirindra RobijaonaNo ratings yet

- The New Income Tax Scandal: How the Income Tax Cheats Workers out of Million$ Each Year and the Corrupt Reasons Why This HappensFrom EverandThe New Income Tax Scandal: How the Income Tax Cheats Workers out of Million$ Each Year and the Corrupt Reasons Why This HappensNo ratings yet

- Ra 9262Document17 pagesRa 9262Lim Xu WinNo ratings yet

- Special Proceedings 3dDocument46 pagesSpecial Proceedings 3dEmilio PahinaNo ratings yet

- Overview On The Ethiopian ConstitutionDocument6 pagesOverview On The Ethiopian ConstitutionAmar Elias100% (1)

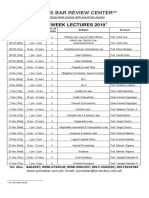

- 2019 Schedule of Preweek LecturesDocument1 page2019 Schedule of Preweek LecturesVioletNo ratings yet

- Kilosbayan V Morato 246 Scra 540Document5 pagesKilosbayan V Morato 246 Scra 540Sheila Eva InumerablesNo ratings yet

- DSWD Services For Youth 06072019Document34 pagesDSWD Services For Youth 06072019Airezelle AguilarNo ratings yet

- Geneva Convention at A GlanceDocument2 pagesGeneva Convention at A GlanceTauqir AhmadNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial Philippine Taxation EvolutionDocument23 pagesPre-Colonial Philippine Taxation EvolutionMarc Edouard100% (1)

- Practice of Law RequirementsDocument2 pagesPractice of Law RequirementsJosephine BercesNo ratings yet

- Think TankDocument22 pagesThink Tanknieotyagi0% (1)

- Labor Federation President Appearance Court AppealsDocument1 pageLabor Federation President Appearance Court AppealslhemnavalNo ratings yet

- Report On Court Room ObservationDocument4 pagesReport On Court Room ObservationVarsha MangtaniNo ratings yet

- Ky. Polling Location LawsuitDocument39 pagesKy. Polling Location LawsuitCourier JournalNo ratings yet

- Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vo.2, No.2, May 2011Document289 pagesMediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vo.2, No.2, May 2011sokolpacukajNo ratings yet

- Garibian SevaneDocument10 pagesGaribian SevaneLuis Eduardo LopezNo ratings yet

- PALE Case Digest AssignmentDocument20 pagesPALE Case Digest AssignmentDiana ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- Case For Substitution of InformationDocument3 pagesCase For Substitution of InformationAnonymous qVBPAB3QwYNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 11 Political Science Executive Revision NotesDocument2 pagesCBSE Class 11 Political Science Executive Revision NotesDevanshiNo ratings yet

- Province of Batangas v. RomuloDocument2 pagesProvince of Batangas v. RomuloGabriel AdoraNo ratings yet

- Roots of English Words. The Program Seemed To Be Intended To Help Introduce EnglishDocument5 pagesRoots of English Words. The Program Seemed To Be Intended To Help Introduce EnglishNatalie JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Newspaper 10 2008Document36 pagesNewspaper 10 2008marketing mix magazine100% (1)

- Consti1 TSN FullDocument46 pagesConsti1 TSN Fulljesryl sugoyanNo ratings yet

- Abellana vs. PonceDocument16 pagesAbellana vs. PonceisaaabelrfNo ratings yet

- Directive PrinciplesDocument15 pagesDirective PrinciplesAkhilDixitNo ratings yet

- Pre - Oral Defense of Group 3Document35 pagesPre - Oral Defense of Group 3Ellie SæxyNo ratings yet

- Export & Import - Winning in the Global Marketplace: A Practical Hands-On Guide to Success in International Business, with 100s of Real-World ExamplesFrom EverandExport & Import - Winning in the Global Marketplace: A Practical Hands-On Guide to Success in International Business, with 100s of Real-World ExamplesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- The Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesFrom EverandThe Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Disloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpFrom EverandDisloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (214)

- The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsFrom EverandThe Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (24)

- Buffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorFrom EverandBuffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- Richardson's Growth Company Guide 5.0: Investors, Deal Structures, Legal StrategiesFrom EverandRichardson's Growth Company Guide 5.0: Investors, Deal Structures, Legal StrategiesNo ratings yet