Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FIDIC in Bahrain

Uploaded by

Ugras SEVGENOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FIDIC in Bahrain

Uploaded by

Ugras SEVGENCopyright:

Available Formats

Society of Construction Law (Gulf) Presentation

FIDIC in the Middle East

Adam Webster, Associate Norton Rose (Middle East) LLP 18 October 2009

1

1.1

Introduction - the legal context of the Middle East

The legal systems of the Middle East are founded upon civil law principles (most heavily influenced by Egyptian law which is itself based on the Napoleonic Code) and Islamic Sharia law, the latter constituting the guiding principle and source of law. The impact of Sharia law depends on the jurisdiction. For example, charging interest is prohibited under Saudi law,

whereas only prohibitive interest will be unenforceable in the UAE. In the UAE and other civil law jurisdictions in the Middle East (including Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Oman), legislation tends to be formulated into a number of major codes providing for general principles of law with a significant amount of subsidiary legislation. Unlike common law jurisdictions, there is little, if any, precedent and we can only surmise what decision a court may arrive at on any given point. 1.2 Although civil codes can give some comfort and confidence to foreign investors and contractors, it ought not to be forgotten that, when it comes to interpreting these codes, all is not always as it seems. While it is true that there are legal principles common to most legal systems, there are many significant differences, and often, in the context of construction and engineering projects, these have the capacity to cause surprise and severe financial discomfort to the unwary. 1.3 Unlike in the UK, countries in the Middle East do not have a specific body of construction or engineering-related law and precedents, despite the fact that particular problems recur time and time again.

The longstanding, but changing relationship between FIDIC and the Middle East

2.1

As most of you will know, the FIDIC forms of contract have been in use in the Middle East since the 1970s. Indeed, the abbreviation FIDIC has become synonymous with the Middle East.

2.2

Historically, the public sector (in Gulf countries especially) has promoted FIDIC as the accepted standard and the private sector has followed suit. There is no apparent rhyme or reason for this, and although FIDIC is the established form of construction contract in the region, it is far from popular. To this end, it is interesting to note that although Abu Dhabi officially adopted the FIDIC form for its standard Government contracts, Dubai has yet to follow suit.

BAH-#450954-v1

2.3

According to a recent survey conducted by our Middle East offices, most developers and contractors responded that they choose to use FIDIC forms largely through habit (indeed 94% of respondents to the survey said that they primarily use FIDIC or modified FIDIC contracts, largely because FIDIC is well-established and recognised within the region). That said, many

respondents also complained that FIDIC is too rigid and breeds an adversarial relationship. The current downturn may give contractors and developers time to reassess their contractual models and consider other forms of contract, including ICE, NEC and partnering contracts. Few

respondents expected that there will be a change in approach towards contracts in the shortterm, however. 2.4 It is somewhat paradoxical that the majority of Middle East countries, who source their law from a mixture of civil and Sharia law, have based their conditions of contract on the FIDIC form despite the fact that the FIDIC conditions of contract are based largely on English common law principles. 2.5 To ensure that any amendments to FIDIC contracts are enforceable in Middle East jurisdictions, it is necessary to have an appreciation for and be aware of any relevant civil code articles in the relevant jurisdictions which may have the practical effect of overriding certain FIDIC conditions. 2.6 Obviously the issues vary from country to country as the local laws are not identical. That said, they are often quite similar and, as such, it is possible to highlight some of the key legal issues that should be borne in mind when advising clients in relation to or negotiating FIDIC based contracts. For instance, some local legal systems require contracts to be registered with the local court at the outset, failing which they might not be valid particularly when the contracts are with government agencies. Similarly, there is often a particular procedure to follow when contracts are terminated. These may involve the local court giving its approval prior to the termination. Perhaps the area fraught with the most problems is how local laws and civil codes deal with the attempt by one party to limit or exclude liability for its own default. Some codes provide that, although the parties may limit the amount of damages by express provision in the contract, the court may, on the application of either party, amend that agreement to render the estimated damages equal to the actual damage. This may come as a rather large surprise to contractors who have sought to limit their liability for delay by reference to liquidated damages. 2.7 All this highlights the dangers of relying on standard forms of international contract, such as FIDIC, which contain clauses in relation to liquidated damages and limitation of liability, for instance, that the unwary might assume are valid the world over. They are not. The message is simple. It is a high-risk strategy to assume that local laws will protect a partys position in the same way that the more familiar common law countries do. 2.8 As such, it is always sensible to instruct a trustworthy local lawyer to ensure that the key clauses upon which you intend to rely are enforceable under the relevant law.

BAH-#450954-v1

2.9

This presentation aims to provide a quick canter through some of the most typical local law considerations. The issues covered do not represent an exhaustive or comprehensive review of construction related local law issues in the region.

2.10

Please note that nothing in this presentation constitutes, or is intended to constitute, advice on local law matters. Norton Rose (Middle East) LLP practises English law and is not permitted to practice Bahraini law (although we have good relations with many local law firms who provide us with Bahraini law advice).

3

3.1

Legal Framework in Bahrain

Legal System The legal system of Bahrain is based on a mixture of English common law models and Sunni and Shia Sharia traditions. For example, family laws are based on Sharia Law, while contract law and civil wrongs are based on principles of English common law. More recent legislation is based on the civil law format taken from the laws of France and Egypt.

3.2

The Constitution The Constitution was suspended in 1975 and revived on 14 February 2002 with substantial amendments by royal decree. The Constitution provides for the separation of the three state powers: legislative, executive and judicial.

3.3 3.3.1

Legislative Branch Legislation can be proposed by the Cabinet or by either of the two houses of the National Assembly: the Shura Council and the Nuwab Council (the Council of Deputies). Each Council has 40 members who serve for four year renewable terms; however, the Shura Councils members are appointed by the King while the Nuwab Council members are elected by 40 separate electoral districts.

3.3.2

Each Council shares in equal part in the legislative process. The King or the Prime Minister will present a bill to the Nuwab Council, which in turn refers the bill to the Shura Council. Each Council may amend or reject the proposed legislation and after passing through each Council, the bill will be transmitted to the King for ratification and promulgation.

3.3.3

For a meeting of the National Assembly to be valid, more than half of its members must be present. Resolutions are passed by an absolute majority of the members present, except in cases where a special majority is required. In the case of a tie, the motion is rejected.

3.3.4

The King has the right to dissolve the Nuwab Council and may also extend its term for up to two years. If it is dissolved, Shura Council sessions are also halted.

BAH-#450954-v1

3.3.5

The King has the right to initiate, ratify and promulgate laws. A bill is considered ratified if a period of six months from the date of its submission by the Shura Council and Nuwab Council has expired without the King returning it for re-consideration. After the King signs the law, the law is published in the Official Gazette and it enters into force.

3.4 3.4.1

Executive Branch The Executive Branch is made up of : (a) (b) (c) King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa

1

3.4.2

The King is chairman of the Higher Judicial Council in which he appoints judges by royal order in accordance with the councils nominations. The Crown Prince is the supreme commander of the defence force. The Prime Minister is appointed directly by the King and is the head of Cabinet.

3.4.3

The King may at any time issue decrees that are enforceable as law but only if they are necessary for taking urgent measures. After such decrees are issued, they are returned to both councils within one month of their promulgation. If the decrees are not referred to the councils or the councils do not ratify them, then the decrees are null and void.

3.5

Judiciary Branch The judiciary is organized into two branches:

3.5.1

The Civil Law Courts: These courts settle all commercial, civil and criminal cases and all cases involving disputes related to the personal status of non-Muslims. These courts are structured in a three-tier system starting with the Courts of Minor Causes (Lower Courts), the High Court of Appeal (Senior Civil Court) and the Supreme Court of Appeal or the Court of Cassation. As a practical matter, the civil courts do not invoke Sharia law except when an issue concerns inheritance.

3.5.2

The Sharia Law Courts: These courts have jurisdiction over all issues related to the personal status of Muslims, both Bahraini and non-Bahraini, and hear matters related to inheritance, gifts, wills and charitable donations. These courts are structured in two levels, the Senior Sharia Court and the High Sharia Court of Appeal.

3.6

1

Local Government

Correct as at 31 August 2008

BAH-#450954-v1

3.6.1

After the political reforms of 2002, five municipal councils corresponding to Bahrains former governates were formed, each managed by an appointed director general.

3.6.2

The Municipal Elections Law of 2002 gives the right to vote for every Bahraini man and woman 21 years or older and also to citizens of other states of the GCC who own property and have residence in Bahrain.

3.7 3.7.1

The Civil Code The prevailing legislation is the Civil Code promulgated by the Legislative Decree No. 19 of 2001.

3.7.2

The Civil Code address a variety of construction law issues, as well as other important issues such as general rules of contracts for work, expiry of contracts, assignment of rights, conditional obligations and time clauses, rules of leases, etc.

3.8 3.8.1

Construction Law in Bahrain Part III, Section I of Civil Code relates to building and construction contracts and covers issues such as: (a) providing materials of work (Articles 585-588) (b) contractors obligations (Articles 589-593) (c) obligations of employer (Articles 594-602) (d) assignment of contract and sub-contracts (Articles 603-606) (e) termination of contracts for work (Articles 607-611)

Local law considerations

FIDIC Red tends to be the most commonly used of the FIDIC contracts in the region (albeit the older 1987 edition). For the purposes of this talk, I will make reference to the 1999 editions of FIDIC Red and Silver. Whilst I will at times make suggestions in this presentation as to how FIDIC might be amended, my primary aim is to offer an understanding of certain local law nuances (not only in Bahrain, but also in the wider region) and how the same might impact on FIDIC Red (or any other book within the FIDIC suite), or any other standard form (or bespoke) contract for that matter.

BAH-#450954-v1

4.1 4.1.1

Applicable Laws Following on from the discussion above in relation to the legal framework and due process of the legal system in Bahrain, we would suggest providing for the following definition of Laws in any contract that is to be governed by Bahraini law: Laws means any Bahraini decree, resolution, law, statute, act, ordinance, rule, directive (to the extent having the force of law), order, treaty, code or regulation or any interpretation of the foregoing or any changes or modification thereof, as enacted, issued or promulgated by any Competent Authority that is publicly available and published in the Official Gazette

4.2 4.2.1

Working Hours and Bahrainisation Care should be taken to ensure that employers do not fall foul of any local labour laws. As such, it is sensible to provide in the contract for working hours to be in accordance with applicable local laws as may, from time to time, be directed by the local authorities.

4.2.2

The wording typically used is as follows: Working Hours shall be in accordance with the relevant Laws applicable to the Works unless the work is unavoidable or necessary for the protection of life or property or for the safety of the Works In addition, the Contractor shall comply with the directives of public authorities with jurisdiction over the Site who may at times request that working hours be reduced or performance of the Works be suspended due to religious holidays, summer working, matters of national security or any other reason. As a result of these directives neither the Contract Price shall be adjusted nor shall the Time for Completion of the Works be extended.

4.2.3

In Bahrain, there is a policy of "Bahrainisation" of which all employers should be aware. This policy was introduced by the Government of Bahrain in order to address a national unemployment problem, whereby local Bahrainis were losing out to expatriate workers, and set targets for the number of Bahrainis employed as a percentage of the employers total labour force. It may be prudent to make express reference to this local policy to ensure that the parties are aware of such local law requirements.

4.2.4

As an aside, it is interesting to note that in January of this year, the Labour Market Regulatory Authority took the decision to reduce the Bahrainisation target for construction companies employing more than 500 workers from 8 to 5 percent of the total number of employees employed by such companies

2

In the UAE, a similar policy known as Emiratisation is in effect

BAH-#450954-v1

4.3 4.3.1

Liquidated Damages FIDIC provides that the Contractor shall pay delay damages to the Employer if it fails to complete the Works, or each section of the Works, by the Time for Completion (subject to any extensions of time). The clause also states that such delay damages shall be the only damages due from the Contractor for such default . The rate of such delay damages is quantified in the Appendix to Tender.

4.3.2

Under English law, the parties are free to agree a rate and a cap of liquidated damages so long as the rate is not extravagant or unconscionable and/or the rate represents a genuine preestimate of the loss that the employer will suffer as a result of the contractors breach. So long as the rate is not penal in nature, is certain or ascertained (i.e. not expressed by way of a complex formula) is not subject to a condition precedent and time is not at large (i.e. the contractor has no right to an extension of time in the event that the employer causes a delay), the liquidated damages agreed at the time the contract was entered into will be upheld by the courts.

4.3.3

Under most regional laws (including Bahrain and the UAE), however, there is considerably more scope for a party to challenge a liquidated damages provision.

4.3.4

Under UAE law, the maximum exposure agreed between the parties by virtue of a cap on liquidated damages may be reviewed by a court or arbitral tribunal exercising its discretion. If actual damage sustained is provable and well in excess of any agreed cap, the court/arbitral tribunal may look beyond the cap and award damages that are quantifiably closer to the actual losses incurred. While this is clearly of benefit to an employer, it is also the case that if the contractor can show that the actual losses sustained by the employer are less than the cap, the court/tribunal may reduce the liquidated damages accordingly. The maximum exposure agreed between the parties by virtue of a cap on liquidated damages may be reviewed by a court exercising its discretion.

4.3.5

Similarly in Bahrain, our understanding is that the courts will not enforce liquidated damages if the party responsible to pay such damages can establish that the other party has not suffered any loss or that the amount fixed was grossly exaggerated or that the principal obligation has been partially performed. However, unlike in the UAE, the court will not award additional

damages over and above any liquidated damages agreed in respect of the same breach, unless the party in default has committed fraud or some other gross error. 4.3.6 Such Civil Code provisions cannot be excluded by agreement between the parties. In reality, therefore, this means that there is little difference between liquidated damages and general damages under most local laws. 4.3.7 The certainty and ability to avoid legal proceedings afforded by liquidated damages under English law is not available.

BAH-#450954-v1

4.4 4.4.1 4.4.2

Limitation / Exclusion of Liability Clauses which limit liability may not be enforceable under local laws. For instance, liability for major structural defects which threaten the total or partial collapse of a building and for any defect that threatens the safety or structural stability of the building cannot, under the laws of most Gulf nations, be limited to a period of less than ten years from the date of practical completion.

4.4.3

Decennial liability (as such liability is known) exists even if there is a defect in the land itself or even if the employer consented to the construction of the defective buildings. A claim for

compensation, however, must be brought within three years of the collapse or discovery of the defect. 4.4.4 The relevant articles of the Civil Code of the UAE and Bahrain setting out the grounds of decennial liability apply to all design and construction contracts, regardless of whether or not they are governed by the local laws. Accordingly, even if English law is nominated as the governing law of a contract, an employer does not forego the benefits of decennial liability (i.e. it is not possible for a contractor to contract out of decennial liability). It should be noted in Bahrain, however, that if it can be proven that the intent of the parties was that the construction should last for less than ten years, the warranty shall be for the period which the structure was intended to last. 4.4.5 It is possible, however, to broaden the scope of decennial liability to cover more than just major structural defects. To this end, I have seen provisions in contracts (such as the one set out below) which attempt to extend the application of decennial liability to all defects in design (as opposed to just those which are likely to cause the partial or total collapse of a building or threaten its safety or stability). The Contractor shall be liable for the consequences of errors, omissions or negligence on its part and in particular it shall be liable for those defects in the design of the Works for which it is responsible pursuant to the Contract, and shall be liable for defects in the construction of any part of the Works if and to the extent that any such defects become apparent during the period of 10 years from the date of the Taking-Over Certificate for that part of the Works and the approval of the Engineer shall not in any way absolve or relieve the Contractor from any such obligation, responsibility or liability. 4.4.6 From an employers perspective, a broad liability of this nature is obviously ideal. Contractors, on the other hand, should be wary of signing up to obligations which go above and beyond the requirements of decennial liability.

BAH-#450954-v1

4.4.7

Of course, not all defects will cause the partial or total collapse of a building or threaten its safety or stability. In such cases, an employer will typically have three years from the date when the defect was discovered or should have been discovered to bring a claim.

4.4.8

If an employer discovers a defect less than three years before the expiry of the decennial liability period, then the liability period of the contractor would be increased.

4.4.9

More generally, where the contract is silent, the Civil Code of the UAE and Bahrain provides for a three year time limit from the date a general defect was discovered (or should have been discovered) for an action to be commenced by an employer. Limitation periods under English law for breach of contract are six or 12 years (depending on whether the contract is signed under hand or as a deed) from the date of the breach or, with respect to latent defects, from the date on which the cause of the action accrues, or (if later) three years from the date of actual knowledge of the defect. Consequently, if the parties wish to agree limitation periods that are longer than three years, or if the governing law of the contract is English law, it would be prudent (when acting for an employer) to make express provision for the limitation period in the contract.

4.4.10

FIDIC seeks to exclude the parties liability for loss of use of any Works, loss of profit, loss of any contract or for any indirect or consequential loss or damage which may be suffered by the other Party in connection with the Contract . There are no clear provisions in the UAE or Bahraini Civil Law codes relating specifically to consequential and indirect losses or, for that matter, any case law as to what constitutes consequential loss. Therefore, provision should be made to ensure that such losses are expressly defined and excluded.

4.4.11

Under Saudi law, Sharia principles determine the scope of compensation and damages. Only actual, direct and proven damages may be awarded in Saudi Arabia; damages for loss of profits, consequential damages or other speculative damages are generally not awarded by the courts in Saudi Arabia.

4.5 4.5.1

Late Payment In certain local law jurisdictions, contractors may be precluded from claiming payment if payment certificates have not been issued in respect of work performed. In such jurisdictions, such as the UAE, careful consideration should be given to the wording of FIDIC or any other standard form or bespoke contract to ensure that time for late payment runs from the date on which the interim and/or final payment certificate, as opposed to the date on which the Contractors application for payment, is made.

4.5.2

Whilst it is acceptable under UAE and Bahraini law for contractual interest (provided not excessive) on late payments of debt (analogous system to English Law) to be agreed and to be charged from the date the amount is due, it may be possible for an Employer to argue that failure to make payment within a period from the date on which the Contractors application for payment is made (as opposed to the date on which the Interim Payment Certificate is issued) does not

BAH-#450954-v1

constitute late payment and, as such, there is no contractual date for interest on late payment to be calculated from. 4.5.3 A main contractor should look to include a pay when paid clause in the subcontract to guard against non-payment by an employer. This is acceptable under local laws and is obviously in stark contrast to Section 113(1) of the HGCR Act 1996 which states that a provision which has the effect of making payment under a "construction contract" (as defined in the Act) conditional on the payer receiving payment from a third person is ineffective, unless that third person, or any other person payment by whom is under the contract (directly or indirectly) a condition of payment by that third person, is insolvent. 4.6 4.6.1 Suspension and Termination Suspension The right to suspend works in the UAE is generally not recognised (unless the contractor is looking to suspend on grounds of delayed payment following the issue of a payment certificate) and the right to terminate is conditional upon a court order being issued. 4.6.2 4.6.3 Termination For the most part, the local laws of most Gulf nations permit parties to a contract to agree on the circumstances in which a contract can be terminated - including provisions which determine the contractors employment, but not all of the contractors obligations under the contract. 4.6.4 In Bahrain, as in Qatar and Egypt, an Employer may terminate a contract and stop work at any time before the completion of the Works, provided he compensates the Contractor for all the expenses the Contractor has incurred for the work completed and the profit he would have made if he had completed the works. The court may, however, on application of the Employer reduce the compensation for loss of profit, if it sees fit. There is no such provision under UAE law, however, and in certain circumstances, a court order may be required to terminate a contract. 4.6.5 We have included drafting in contracts governed by UAE law stating that the parties agree that they may be terminated without a court order if such termination is in accordance with the termination provisions, but it is not certain that this will be effective if challenged. 4.7 4.7.1 Assignment and Novation FIDIC provides that neither party shall assign the whole or any part of the Contract or any benefit or any interest in or under the Contract However, either Party may assign 4.7.2 There is no concept of novation in the Middle East and assignment refers not only to a transfer of rights, but also obligations. As such, it is important to make clear in the drafting what it is that is intended to be capable of being transferred i.e. rights and/or obligations under the contract.

BAH-#450954-v1

4.7.3

In any event, a tripartite agreement (similar to a novation agreement under English law) is required to transfer both rights and obligations.

4.8 4.8.1

Boycott on Israel Many of the construction contracts that we see contain a provision which attempts to impose an obligation on the contractor to boycott trade with Israel.

4.8.2

However, now that Bahrain has entered into a Free Trade Agreement with the USA, such a provision will be unenforceable.

5

5.1

Choice of law

Parties are free under all Gulf laws to choose and agree the governing law of the contract that they intend to enter into. Obviously, in certain circumstances, the law of the contract may be influenced or determined by the identity of one or more of the parties. For instance, government bodies and entities will typically require the governing law of any contract entered into with a private entity to be the local law of the country to which that government body or entity belongs.

5.2

With respect to local laws, there are clearly some benefits of making English law the governing law of a contract. For instance: (a) Under English law, parties can predict (with greater certainty than under many other legal systems) whether a proposed course of action is likely to be lawful or unlawful. By contrast, as we have considered, local laws in the Gulf are based on a combination of Sharia and civil law (Egyptian and French) systems which do not employ the concepts of case law and/or precedence. (b) English courts have previously considered the terms and conditions of most of the international standard form construction contracts, such as the FIDIC standard form agreements. This accumulated case law creates certainty and possibly assists in any future disputes which may arise about the interpretation of key project documentation. (c) Limitation periods under English law, as discussed above, tend to be more favourable than those provided under most local laws for breach of contract (save in respect of decennial liability).

5.3

There are, however, some aspects relating to the selection of English law as the governing law of the contract which parties should be aware of, including: (a) There may be issues about the ability of the parties to access the Bahrain Court of Urgent Matters for urgent interlocutory relief; and

BAH-#450954-v1

(b) There may also be issues which arise in relation to consistency between the head contracts (governed by English law) and smaller subcontracts (which would typically be subject to Bahraini law).

BAH-#450954-v1

You might also like

- Construction Law in the United Arab Emirates and the GulfFrom EverandConstruction Law in the United Arab Emirates and the GulfRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Contract Vs UAE Law PDFDocument12 pagesContract Vs UAE Law PDFRiyas0% (1)

- Form of Tender and Appendix To TenderDocument4 pagesForm of Tender and Appendix To Tendernandini2309No ratings yet

- Cornes and Lupton's Design Liability in the Construction IndustryFrom EverandCornes and Lupton's Design Liability in the Construction IndustryNo ratings yet

- NEC3 Early Warning and Compensation EventsDocument5 pagesNEC3 Early Warning and Compensation Eventsjon3803100% (1)

- A Contractor's Guide to the FIDIC Conditions of ContractFrom EverandA Contractor's Guide to the FIDIC Conditions of ContractNo ratings yet

- Construction Dynamics Solutions - OverviewDocument4 pagesConstruction Dynamics Solutions - OverviewkkkkkNo ratings yet

- Multi-Party and Multi-Contract Arbitration in the Construction IndustryFrom EverandMulti-Party and Multi-Contract Arbitration in the Construction IndustryNo ratings yet

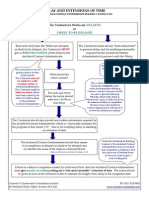

- Extension of Time Under JCT (Illustration)Document1 pageExtension of Time Under JCT (Illustration)LGNo ratings yet

- Conditions of Contract For Construction: 1.1 DefinitionsDocument8 pagesConditions of Contract For Construction: 1.1 DefinitionskamalNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide to Disruption and Productivity Loss on Construction and Engineering ProjectsFrom EverandA Practical Guide to Disruption and Productivity Loss on Construction and Engineering ProjectsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Nick Gould - Standard Forms JCT 2005Document32 pagesNick Gould - Standard Forms JCT 2005John WoodNo ratings yet

- EOT Claim for 47 Day Extension Due to Design ChangesDocument22 pagesEOT Claim for 47 Day Extension Due to Design ChangesHany kassabNo ratings yet

- Construction Claims and Responses: Effective Writing and PresentationFrom EverandConstruction Claims and Responses: Effective Writing and PresentationNo ratings yet

- Claims Chart Under FIDICDocument4 pagesClaims Chart Under FIDICMohamad Hessen100% (1)

- Practical Guide to the NEC3 Professional Services ContractFrom EverandPractical Guide to the NEC3 Professional Services ContractNo ratings yet

- Time at Large and Reasonable Time For CompletionDocument105 pagesTime at Large and Reasonable Time For Completionmohammad_fazreeNo ratings yet

- Delay and DisruptionDocument24 pagesDelay and Disruptionasif iqbalNo ratings yet

- The FIDIC Contracts: Obligations of the PartiesFrom EverandThe FIDIC Contracts: Obligations of the PartiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- FCCMDocument2 pagesFCCMMohanna Govind100% (1)

- Issue RED BOOK (1999) YELLOW BOOK (1999) SILVER BOOK (1999) : Regulation and WorksDocument34 pagesIssue RED BOOK (1999) YELLOW BOOK (1999) SILVER BOOK (1999) : Regulation and WorksPrabath ChammikaNo ratings yet

- Commentary:: Amending Clause 13.1 of FIDIC - Protracted NegotiationsDocument2 pagesCommentary:: Amending Clause 13.1 of FIDIC - Protracted NegotiationsArshad MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Additional Payment Under FIDIC - DonaDocument12 pagesAdditional Payment Under FIDIC - DonaAldy RifalldyNo ratings yet

- Contract Administration Core Curriculum Participant's Manual and Reference Guide 2006Document198 pagesContract Administration Core Curriculum Participant's Manual and Reference Guide 2006Larry Lyon100% (1)

- FIDIC COVID-19 Guidance MemorandumDocument14 pagesFIDIC COVID-19 Guidance Memorandumhz135874100% (1)

- Comments On FIDIC 2017Document2 pagesComments On FIDIC 2017Magdy El-GhobashyNo ratings yet

- Fidic Red Book 2017 - A Mena PerspectiveDocument8 pagesFidic Red Book 2017 - A Mena PerspectiveDavid MorgadoNo ratings yet

- Construction Contracts GuideDocument5 pagesConstruction Contracts Guidejunlab0807100% (1)

- Fidic Variation PDFDocument268 pagesFidic Variation PDFjohnpaul100% (1)

- Employer Contractor Claims ProcedureDocument2 pagesEmployer Contractor Claims ProcedureNishant Singh100% (1)

- Session 2 - FIDIC Notices - Deadlines - Responsibilities & Actions of The Parties (To Share)Document76 pagesSession 2 - FIDIC Notices - Deadlines - Responsibilities & Actions of The Parties (To Share)m Edwin100% (1)

- Construction Claim - ILQ - Fall - 2014Document72 pagesConstruction Claim - ILQ - Fall - 2014A SetiadiNo ratings yet

- A Legal Analysis of Some ScheduleDocument17 pagesA Legal Analysis of Some Scheduledrcss5327No ratings yet

- Contract ExamDocument5 pagesContract ExamYeowkoon ChinNo ratings yet

- Extension of Time ClaimsDocument2 pagesExtension of Time ClaimsindikumaNo ratings yet

- MPL Article Managing An NEC3 ProgrammeDocument9 pagesMPL Article Managing An NEC3 Programmecv21joNo ratings yet

- Accelaration Cost On ProjectsDocument13 pagesAccelaration Cost On ProjectsWasimuddin SheikhNo ratings yet

- What Are The Differences Between FIDIC 1999 and 2017 Claims Resolution Procedures - Contract BitesDocument9 pagesWhat Are The Differences Between FIDIC 1999 and 2017 Claims Resolution Procedures - Contract BitesahamedmubeenNo ratings yet

- Fidic ClauseDocument53 pagesFidic Clauseehtsham007No ratings yet

- The Role of The Employer&Contractor-FIDICDocument6 pagesThe Role of The Employer&Contractor-FIDICJared Makori100% (1)

- Contractor Claims For Prolongation Costs - A Comprehensive Guide - LexologyDocument7 pagesContractor Claims For Prolongation Costs - A Comprehensive Guide - LexologyVishal ButalaNo ratings yet

- FIDIC DisputesDocument3 pagesFIDIC DisputeserrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- FIDIC - 10 Things To KnowDocument7 pagesFIDIC - 10 Things To KnowSheron AnushkeNo ratings yet

- What Is Contract Management?Document25 pagesWhat Is Contract Management?Muhammad BasitNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Online Courses and Training ProgrammeDocument3 pagesFIDIC Online Courses and Training ProgrammePravin MasalgeNo ratings yet

- Loss and Expense ClaimsDocument28 pagesLoss and Expense ClaimsJama 'Figo' MustafaNo ratings yet

- Fidic InfoDocument39 pagesFidic InfoAMTRIS50% (2)

- Sub-Contracts Management and AdministrationDocument76 pagesSub-Contracts Management and Administration3FoldTrainingNo ratings yet

- Disruption PDFDocument9 pagesDisruption PDFOsmanRafaeeNo ratings yet

- FIDIC or IChemE Which Is BestDocument1 pageFIDIC or IChemE Which Is BestfalnaimiNo ratings yet

- RED Book Vs Civil Code by AnandaDocument35 pagesRED Book Vs Civil Code by AnandalinkdanuNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To FIDIC and FIDIC Contract BooksDocument15 pagesAn Introduction To FIDIC and FIDIC Contract Booksaniket100% (1)

- FIDIC: Termination by The Employer Under The Red and Yellow BooksDocument8 pagesFIDIC: Termination by The Employer Under The Red and Yellow BookssaihereNo ratings yet

- Handling Prolongation ClaimsDocument17 pagesHandling Prolongation ClaimsShakthi ThiyageswaranNo ratings yet

- Home Owner Building Contract No Consultant AppointedDocument17 pagesHome Owner Building Contract No Consultant AppointedmustafaNo ratings yet

- FIDIC (Conditions of Particular Application With Guidelines)Document32 pagesFIDIC (Conditions of Particular Application With Guidelines)Ugras SEVGEN100% (1)

- Vector Calculus - Theodore VoronovDocument49 pagesVector Calculus - Theodore VoronovUgras SEVGEN100% (2)

- (Ebook-Pdf) - Mathematics - Alder - Multivariate CalculusDocument197 pages(Ebook-Pdf) - Mathematics - Alder - Multivariate CalculusmjkNo ratings yet

- Adv Calculus and AnalysisDocument110 pagesAdv Calculus and AnalysisAshok PhoenixNo ratings yet

- Julius O. Smith - Mathematics of The Discrete Fourier TransformDocument247 pagesJulius O. Smith - Mathematics of The Discrete Fourier Transformpsps46No ratings yet

- Remedies For Breach of ContractDocument18 pagesRemedies For Breach of ContractNitin DhaterwalNo ratings yet

- Amon Trading Corp V CADocument3 pagesAmon Trading Corp V CASocNo ratings yet

- Bar Exam Quasi-ContractsDocument4 pagesBar Exam Quasi-ContractsmrvirginesNo ratings yet

- L.G. Foods Corporation and Victorino Gabor Vs - Pagapong-AgraviadoDocument2 pagesL.G. Foods Corporation and Victorino Gabor Vs - Pagapong-AgraviadoMigoy DANo ratings yet

- Reliance Two Wheeler Insurance Policy DetailsDocument2 pagesReliance Two Wheeler Insurance Policy DetailsRoopesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Mutual Termination and Release AgreementDocument5 pagesMutual Termination and Release AgreementMohamed El AbanyNo ratings yet

- Chase Vs CFI of Manila (The Taliño)Document2 pagesChase Vs CFI of Manila (The Taliño)AlexandraSoledadNo ratings yet

- 65 State Investment House vs. IACDocument4 pages65 State Investment House vs. IACCharm Divina LascotaNo ratings yet

- Marginal Fishermen Rights vs LGU OrdinancesDocument2 pagesMarginal Fishermen Rights vs LGU OrdinancesPatricia BautistaNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Project Charter - 25 Aug 2011Document15 pagesProcedure For Project Charter - 25 Aug 2011Atif Mumtaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Shauf Vs Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesShauf Vs Court of AppealsRA BautistaNo ratings yet

- Estate settlement hinges on child's filiationDocument8 pagesEstate settlement hinges on child's filiationLizzette Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Against Citizenship Bid Due to Omitted ChildrenDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Rules Against Citizenship Bid Due to Omitted ChildrenDebbie YrreverreNo ratings yet

- Grana and Torralba V CA FulltextDocument3 pagesGrana and Torralba V CA FulltextBandar TingaoNo ratings yet

- Manzanares v. Elko County School District Et Al - Document No. 47Document2 pagesManzanares v. Elko County School District Et Al - Document No. 47Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affdavit RuleDocument4 pagesJudicial Affdavit RuleAngel UrbanoNo ratings yet

- 124 - Sec. of Education v. CADocument2 pages124 - Sec. of Education v. CAAlexis Elaine BeaNo ratings yet

- CPCCSA NshyaDocument250 pagesCPCCSA NshyaBernard Palmer0% (1)

- Dolan Et Al. v. Altice USA Inc. Et Al. - Verified ComplaintDocument347 pagesDolan Et Al. v. Altice USA Inc. Et Al. - Verified ComplaintAnonymous g2k2l9b100% (1)

- Civil Law - ObliconDocument142 pagesCivil Law - Obliconkrosophia100% (1)

- Memorandum in Opposition To Summary Judgment Harley 11 2009Document13 pagesMemorandum in Opposition To Summary Judgment Harley 11 2009AC Field100% (2)

- Digest Crim ProDocument7 pagesDigest Crim ProCherlene TanNo ratings yet

- Domingo Neypes Vs Court of AppealsDocument1 pageDomingo Neypes Vs Court of AppealsAurora Pelagio VallejosNo ratings yet

- Free Patent JurisprudenceDocument12 pagesFree Patent JurisprudenceAdelito M Solibaga JrNo ratings yet

- Clra 1970Document37 pagesClra 1970Rituparna MallickNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Law Journal Volume 7 Issue 02Document6 pagesThe Cambridge Law Journal Volume 7 Issue 02KkkNo ratings yet

- UP Law Remedial Law Review OutlineDocument30 pagesUP Law Remedial Law Review OutlineChristian Paul LugoNo ratings yet

- Mapalo v. Mapalo (1966)Document5 pagesMapalo v. Mapalo (1966)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Colonel Gregory Hollister v. Barry Soetoro - Supreme Court Order List Page 11 - Denied - 3/7/2011Document12 pagesColonel Gregory Hollister v. Barry Soetoro - Supreme Court Order List Page 11 - Denied - 3/7/2011ObamaRelease YourRecordsNo ratings yet

- 5 Indemnity Bond in Lieu of Proof of OwnershipDocument3 pages5 Indemnity Bond in Lieu of Proof of OwnershipDamodar AggarwalNo ratings yet

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- IFRS 9 and CECL Credit Risk Modelling and Validation: A Practical Guide with Examples Worked in R and SASFrom EverandIFRS 9 and CECL Credit Risk Modelling and Validation: A Practical Guide with Examples Worked in R and SASRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- The Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesFrom EverandThe Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Getting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorFrom EverandGetting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Dealing With Problem Employees: How to Manage Performance & Personal Issues in the WorkplaceFrom EverandDealing With Problem Employees: How to Manage Performance & Personal Issues in the WorkplaceNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Disloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpFrom EverandDisloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (214)

- Buffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorFrom EverandBuffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- The Business Legal Lifecycle US Edition: How To Successfully Navigate Your Way From Start Up To SuccessFrom EverandThe Business Legal Lifecycle US Edition: How To Successfully Navigate Your Way From Start Up To SuccessNo ratings yet

- The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsFrom EverandThe Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (24)

- Ben & Jerry's Double-Dip Capitalism: Lead With Your Values and Make Money TooFrom EverandBen & Jerry's Double-Dip Capitalism: Lead With Your Values and Make Money TooRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the PublicFrom EverandThe Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the PublicRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Global Bank Regulation: Principles and PoliciesFrom EverandGlobal Bank Regulation: Principles and PoliciesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesFrom EverandThe Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Motley Fool's Rule Makers, Rule Breakers: The Foolish Guide to Picking StocksFrom EverandThe Motley Fool's Rule Makers, Rule Breakers: The Foolish Guide to Picking StocksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Export & Import - Winning in the Global Marketplace: A Practical Hands-On Guide to Success in International Business, with 100s of Real-World ExamplesFrom EverandExport & Import - Winning in the Global Marketplace: A Practical Hands-On Guide to Success in International Business, with 100s of Real-World ExamplesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The HR Answer Book: An Indispensable Guide for Managers and Human Resources ProfessionalsFrom EverandThe HR Answer Book: An Indispensable Guide for Managers and Human Resources ProfessionalsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Wall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementFrom EverandWall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)