Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Motivation

Uploaded by

Piolo PascualOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Motivation

Uploaded by

Piolo PascualCopyright:

Available Formats

What was your primary motive for participating in the Leadership Living Learning Community According to the Association

of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) (2002), students are flocking to college because the world is complex, turbulent, and more reliant on knowledge than ever before (p. viii). Teaching these students about leadership and their development as leaders is becoming increasingly more important to colleges and universities across the country (Cress, Astin, Zimmerman-Oster, & Burkhardt, 2001). However, some would argue that our education practice has emphasized information transfer without a great deal of thought given to the meaning, pertinence, or application of the information in the context of the students life (Keeling, 2004, p. 10). In other words, academic learning and student development have often been viewed separately from each other (Keeling). This notion is supported by Minor (1997) who noted that faculty often think of courses taking place only in traditional classroom settings while residence hall programs focus on dimensions of student development. What is needed is the view of learning as a comprehensive, holistic, transformative activity that integrates academic learning and student development (Keeling, 2004, p. 4). In his book Achieving Educational Excellence, Alexander Astin describes learning communities as small sub-groups of studentscharacterized by a common sense of purposethat can be used to build a sense of group identity, cohesiveness and uniqueness that encourages continuity and the integration of diverse curricular and co-curricular experiences (Minor, 1997, p. 21). Minor noted that while students who are coenrolled in common courses, a typical practice in learning communities, might exhibit many characteristics that describe learning communities as defined by Astin, the potential for their success is significantly enhanced by making use of a location where a majority of freshman spend most of their time the residence halls (p. 21). Keeling (2004) described student affairs and academic affairs partnerships, such as residential learning communities in which students are all enrolled in one or more of the same classes and live together, as an example of a transformative learning opportunity for students. According to Keeling, these powerful partnerships, jointly planned, combine knowledge acquisition and experiential learning to promote more complex outcomes (p. 20). Residential learning communities require that faculty members and student affairs professionals come together for the overriding purpose of the college experience: educating the same students together (Gablenick, MacGregor, Matthews, & Smith, 1990, p. 91). learning communities foster development of supportive peer groups, greater student involvement in the classroom learning and social activities, perceptions of greater academic development, and greater integration of students academic and nonacademic lives (p. 423). Gabelnick et al. (1990) ultimately identified eight themes related to what students value about their experiences in a learning community including friendships and a sense of belonging, learning collaboratively, intellectual energy and confidence, appreciation of other students perspectives, discovering texts, the building of intellectual connections, embracing complexity, and new perspectives on their own learning process. The question must be asked, What motivates first-year students to participate in optional residential learning communities that require both in-class and out-ofclass experiences? This study sought to explore the motives behind student

participation in a voluntary, residential learning community that focused on leadership at Texas A&M University. The students were all traditional-aged, incoming first-year students, and in addition to enrolling in a one-credit academic class focused on leadership each semester of their first year, they also agreed to live on the same floor of an on-campus residence hall. Theoretical Framework The theoretical framework for this study was rooted in McClellands Achievement Motivation Theory. Achievement Motivation Theory attempts to explain and predict behavior and performance based on a persons need for achievement, power, and affiliation (Lussier & Achua, 2007, p. 42). The Achievement Motivation Theory is also referred to as the Acquired Needs Theory or the Learned Needs Theory. Daft (2008) defined the Acquired Needs Theory as McClellands theory that proposes that certain types of needs (achievement, affiliation, power) are acquired during an individuals lifetime (p. 233). The Achievement Motivation Theory evolved from work McClelland began in the 1940s. In 1958 McClelland described human motives in the Methods of Measuring Human Motivation chapter of Atkinsons book, Motives in Fantasy, Action, and Society. At that point, McClelland identified human motives related to the achievement motive, the affiliation motive, the sexual motive, and the power motive. In his later work, The Achieving Society (McClelland, 1961), however, McClelland focused his attention on only need for Achievement, the need for Affiliation, and the need for Power. In essence, McClellands theory postulates that people are motivated in varying degrees by their need for Achievement, need for Power, and need for Affiliation and that these needs are acquired, or learned, during an individuals lifetime (Daft, 2008; Lussier & Achua, 2007). In other words, most people possess and will exhibit a combination of three needs. Need for Achievement McClelland, Atkinson, Clark, and Lowell (1958) defined the need for Achievement (n Achievement) as success in competition with some standard of excellence. That is, the goal of some individual in the story is to be successful in terms of competition with some standard of excellence. The individual may fail to achieve this goal, but the concern over competition with a standard of excellence still enables one to identify the goal sought as an achievement goal. This, then, is our generic definition of n Achievement (p. 181). McClelland et al. (1958) went on to describe that competition with a standard of excellence was most notable when an individual was in direct competition with someone else but that it can also be evident in the concern for how well one individual performs a task, regardless of how someone else is doing. According to Lussier and Achua (2007), the need for achievement is the unconscious concern for excellence in accomplishments through individual efforts (p. 42). Similarly, Daft (2008) stated the need for Achievement is the desire to accomplish something difficult, attain a high standard of success, master complex tasks, and surpass others (p. 233). Individuals who exhibit the need for Achievement seek to accomplish realistic but challenging goals Need for Power McClelland (1961) defined the need for Power as a concern with the control of the means of influencing a person (p. 167). Lussier and Achua (2007) defined the need for Power as the unconscious concern for influencing others and seeking positions of authority (p. 42). Similarly, Daft (2008) defined the need for Power as the desire to influence or control others, be responsible for others, and

have authority over others (p. 233). Individuals who exhibit the need for Power have a desire to be influential and want to make an impact. Need for Affiliation When defining the need for Affiliation, McClelland (1961) stated, Affiliationestablishing, maintaining, or restoring a positive affective relationship with another person. This relationship is most adequately described by the word friendship (p. 160). Therefore, the need for affiliation is the unconscious concern for developing, maintaining, and restoring close personal relationships (Lussier & Achua, 2007, p. 43). Daft (2008) defined the need for Affiliation as the desire to form close personal relationships, avoid conflict, and establish warm friendships (p. 233). Individuals who exhibit the need for Affiliation are seeking interactions with other people. Content analysis of the responses revealed incoming freshmen students were motivated to participate in the L3C primarily because of the need for Achievement and the need for Affiliation. While all three needs were detected in the student comments, the need for Power was not as pervasive in the comments as the need for Achievement and the need for Affiliation. The need for Achievement was evident in the statements written by the students. Within this need, common phrases included wanting to gain leadership skills, expand leadership abilities, and to learn how to become a better leader. Student comments demonstrating the need for Achievement are included: I wanted to further myself in as a leader in all aspects of my life, but also because I plan on being a teacher and want to be as affective a leader as possible. (87) My primary motivation was improving my leadership skills which I believe are essential in my life. (12) I also wanted to enhance my leadership abilities. (82) I wanted to challenge myself as a person step outside my comfort zone and better understand what it takes to be a good leader. (89) To further and better my leadership skills. (30) Forty of the 89 students (44.94%) demonstrated the Need for Achievement in their responses. The need for Affiliation was also often identified within the statements. Within this need, phrases such as students desire to meet people, establish friendships, and develop a sense of community were common. Student comments demonstrating the need for Affiliation are included: My primary motivation for joining the L3C was so I could be a part of a close-knit community my first year of college. (13) I thought be a good way to meet fellow freshmen and grow good relationships with them. (65) The Leadership Learning Community sounded like a close-knit family, and what I really needed to feel safer at such a big university was people who had things in common with me. (55) One of the primary reasons was that being a part of L3C would help facilitate my networks as I begin college life. Along with having people who I can depend on if I fall short on anything. (59) I wanted to have a smaller community of people that I could get close to in such a huge university. (66) Thirty-nine of the 89 students (43.82%) demonstrated the need for Affiliation in their responses

The need for Power was less evident in the responses to the open-ended question. Students who expressed the need for Power included in their responses the desire to serve in leadership roles or positions. I have always been involved and loved leadership positions. The reason for joining L3C is to become active in leadership roles and events my first year at Texas A&M. (4) I was a big fish in a little pond in high school, so I felt that joining the L3C would give me leadership roles during my first year at TAMU. I felt that it would also help give me an instant group once I arrived on campus. (10) I want to learn how to be a better leader and be able to organize people in a productive way without breeding contempt. (29) Only eight of the 89 students (8.99%) demonstrated the need for Power in their responses. By analyzing student comments from an open-ended question, the researchers were able to conclude that incoming first-year students were motivated to participate in a voluntary, residential leadership learning community based on the three needs identified by McClelland (1958, 1961), primarily the need for Achievement and the need for Affiliation. Students expressed their needs to make new friends and to develop leadership knowledge, skills, and abilities. Because the words living, community, and leadership are all in the title of the program, it is possible that the initial question asking students what was their primary motive for participating in the Leadership Living Learning Community was leading, therefore prompting students to include affiliation and achievement related comments. The fact that student comments demonstrated a clear need for both achievement and affiliation supports the work of Minor (1997) and Keeling (2004) who noted the need to view learning more holistically and to integrate academic life with residence life to create transformative learning experiences for students. The demonstrated need for Achievement clearly indicates the need for strong academic programs. Similarly, the demonstrated need for Affiliation clearly indicates the need for strong residential life programs. The benefits for students come when strong academic programs and strong residential programs are integrated. Because almost as many comments reflected the need for Achievement and the need for Affiliation, program coordinators and instructors need to ensure that there is a balance of both academic achievement and social affiliation, thus requiring a continued partnership between the academic department and student affairs. It is not surprising that this group of students clearly demonstrated the need for Achievement. In essence this finding is consistent with the findings of the studies from the University of Oregon and the Washington Center for Undergraduate Education cited in Gabelnick et al. (1990) which showed students in learning communities had slightly higher expectations about their academic success than freshman who were not enrolled in a learning community. This is also consistent with the findings the Johnson et al. (1998) study cited in Pascarella and Terenzini (2005) which showed that students in learning communities help perceptions of greater academic achievement. Because for many students, starting college means leaving their friends and families behind, it is not surprising that students entering their first year in college would demonstrate the need for Affiliation. This finding supports findings of the University of Oregon study (cited in Geblenick, et al., 1990) that showed FIG

students were a little more anxious that other freshman about making friends. A possible explanation for such a finding can be found in Schlossbergs Transition Theory (Schlossberg, 1981, 1984) which includes a framework for human adaptation to transition. Within the theory there are four stages: situation, self, support, and strategies. The support stage is characterized by finding types of social supports a person has become accustomed to in their previous environment. Social supports can include: intimate relationships, family units, networks of friends, and institutions and communities (p. 107). The need for Power was not as common in the comments of the students. It appeared as though students were more focused on the concept of learning leadership rather than practicing leadership within specific leadership roles. Komives, Longerbeam, Owen, Mainella, and Osteen (2006) proposed a model of leadership identity development in which individuals progress from Stage One: Awareness, through Exploration/Engagement, Leader Identified, Leadership Differentiated, and Generativity to Stage Six: Integration/Synthesis. Participants in their study entered college in the Leader Identified stage in which students were fully involved in organizations, but were only leaders if they have positional leadership, otherwise they were followers. Perhaps because these students were incoming freshmen they had not yet progressed through their leadership identity development to Stages Four, Five, and Six where they were actively seeking leadership opportunities and exhibit the desire to influence others. McClellands research showed that only about 10 percent of the U.S. population has a strong dominant need for achievement (Lussier & Achua, 2007, p. 42). While it was beyond the scope of this study to measure the strength of students need for Achievement, it is interesting to note that almost half of the students (44.94%) in this study made reference to the need for Achievement in their responses.

The work of Leithwood and Montgomery (1984) is especially helpful in understanding the relationship of motivation to effective leadership 5 and school goals because it addresses the principals motivation to become a more effective leader as well as the students motivation to learn. They describe four stages that principals go through in the process of becoming more and more effective as school leaders. The first, and least effective, stage, administrator, is characterized by the principals desire simply to run a smooth ship. At the second stage, humanitarian, principals focus primarily on goals that cultivate good interpersonal relations, especially among school staff. Principals at the third stage, program manager, perceive interpersonal relations as an avenue for achieving school-level goals that stress educational achievement. At the fourth and highest stage, systematic problem solver, principals become devoted to a legitimate, comprehensive set of goals for students, and seek out the most effective means for

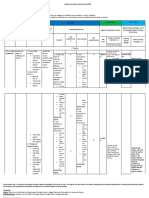

their achievement (p. 51). One of the chief characteristics of highly effective principals at the systematic problemsolver stage is the ability to transfer their own desire and motivation to achieve valued goals to the other participants in the educational process. As Leithwood and Montgomery comment: Highly effective principals . . . seek out opportunities to clarify goals with staff, students, parents and other relevant members of the school community. They strive toward consensus about these goals and actively encourage the use of such goals in departmental and divisional planning. Such behaviour can be explained by the principals knowledge of human functioning and the actions consistent with such knowledge. Highly effective principals appear to understand that school improvement goals will only direct the actions of staff, students and others to the extent that these people also adopt them as their own. Increases in principal effectiveness can be explained as increases in opportunities, provided by the principal, for all relevant others to agree upon and internalize approximately the same set of school improvement goals. (p. 31) According to Leithwood and Montgomery, as principals become more and more effective, they come to understand that people will not be motivated unless they believe in the value of acting to achieve a particular goal: People are normally motivated to engage in behaviours which they believe will contribute to goal achievement. The strength of ones motivation to act depends on the importance attached to the goal in question and ones judgement about its achievability; motivational strength also depends on ones judgement about how successful a particular behavior will be in moving toward goal achievement. (p. 31) Motivation on the part of the principal translates into motivation among students and staff through the functioning of goals, according to Leithwood and Montgomery. Personally valued goals, they say, are a central element in the principals motivational structurea stimulus for action (p. 24). In a related study, Klug (1989) describes a measurement-based approach for analyzing the effectiveness of instructional leaders and provides a convenient model for understanding the principals influence on student achievement and motivation. The model is shown in figure 1. Klug notes that school leaders can have both

direct and indirect impact on the level of motivation and achievement within two of the three areas shown in figure 1. Although the personal factorsdifferences in ability levels and personalities of individual studentsusually fall outside a school leaders domain of influence, the other two categories, situational factors and motivational factors, are to some degree within a school leaders power to control. Klugs summary of the model describes how these two areas can be a source of influence: School leaders enter the achievement equation both directly and indirectly. By exercising certain behaviors that facilitate learning, they directly control situational (S) factors in which learning occurs. By shaping the schools instructional climate, thereby influencing the attitudes of teachers, students, parents, and the community at large toward education, they increase both student and teacher motivation and indirectly impact learning gains. (p. 253) There are many strategies school leaders can use to reward motivation and promote academic achievement. For example, Huddle (1984), in a review of literature on effective leadership, cites a study in which principals in effective schools used a variety of methods to publicize the school goals and achievements in the area of academics. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation There are basic differences in sources of motivation. According to the Center for Educational Research and Innovation (2000): Intrinsically-motivated students are said to employ strategies that demand more effort and that enable them to process information more deeply. Extrinsically-motivated students, by contrast, are inclined to make the minimum effort to achieve an award. Older behaviourist perspectives on motivation assumed that teachers could manipulate childrens engagement with schoolwork through the introduction of controls and rewards. However, research has tended to show that children usually revert to their original behaviour when the rewards stop. Furthermore, at least two dozen studies have shown that people expecting to receive a reward for completing a taskor for doing it successfullydo not perform as well as InSight: A Collection of Faculty Scholarship 15 Intrinsic motivation has been the focus of study by educational psychologists and has its roots in selfdetermination theory: In Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) we distinguish between different types of motivation based on the different reasons or goals that gives rise to an action. The most basic distinction is between intrinsic motivation, which refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable, and extrinsic motivation, which refers to doing something because it leads to a separable outcome. Over three decades of research has shown that the quality of experience and performance can be very different when one is behaving for intrinsic versus extrinsic reasons. (Reeve, Deci, & Ryan, 2004, pp. 31-60) Additionally, Banduras work (1993) on self-efficacy in cognitive development has made significant

contributions to the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Students 16 Volume 2, Student Motivation, 2007 who are intrinsically motivated are more likely to credit their successes to internal factors such as the amount of effort they invest. They also believe that they can take credit for the results of their efforts rather than attribute them to luck. Intrinsically motivated students strive for a deep understanding and mastery of the material rather than simply memorization of facts. The benefit of intrinsic motivation is its availability and portability. If what drives one to succeed is based on factors that derive from ones own beliefs, morals, desires, and goals, then access to those motivators is instant and not dependent on the availability or cooperation of external sources such as money or motivational speakers. The reward of acquiring knowledge or critical thinking skills comes from a personal sense of accomplishment that one has somehow grown as an individual; achievement of personal goals outweighs any external reward. External gratification, while desirable and not to be discounted, is secondary to an internal sense of accomplishment. At what point do human beings develop a preference for an intrinsic rather than an extrinsic source of motivation? Knowles (1984) points out that growing older, the mature adult becomes more independent, and wholly self-directing. When a person becomes older, his motivation to learn comes more from his own self (p 12). Colleges and universities are experiencing a changing demographic, from one of college freshmen who enroll directly from high school to one of adult learners with significant life experiences. The methods of education and the dynamics of the classroom or online class must change to accommodate the adult or mature learner.

those who expect nothing. This appears to be true for children and adults, for males and females, for rewards of all kinds and for tasks ranging from memorising facts to designing collages. (p. 27) In traditional settings of higher education, students are motivated by a variety of internal and external stimuli. Motivating external stimuli can include, but are not limited to, a quest for a college degree or knowledge, opportunity for career enhancement or entrance into a career, grades, fear of failure or avoidance of shame (grading), personal recognition, money, externally set goals, pleasing the

instructor, pleasing ones parents, friends, or colleagues, etc; the list of external motivators goes on. External motivators are often culturally driven and observable. School is a great place to try new things - join clubs, audition for the lead in the school play, try out for the track team and even get involved in student council. Being a member of student council allows you to take action, especially if you have a school complaint. So get involved in your school's student council, raise your voice and make a difference. Student Council - Why Get Involved? Joining student council is a fun way to get involved with your school. And it's a great way to make friends and meet new peeps - improving school issues will definitely get you noticed around the hallways. More importantly, if you have a school complaint, whether it's about class sizes or teacher availability, then you can help to bring about a change by taking a stance and standing up for students' rights. Getting involved gives you the opportunity to improve issues and make your school a better place.

1. Make a difference for the student body Decisions made in UPUA can affect the entire student body. As a student leader, you have a voice in what is being done at this university. Projects like the Student Representative on the Borough Council and the White Loop Extension are just a few of UPUAs numerous accomplishments. If you would like to help build on past successes and create future achievements, running for UPUA is a great way to serve constituents. 2. Build a larger network Serving as a representative gives you the opportunity to meet and collaborate with a wide array of people, both fellow students, faculty, and administrators. These connections will not only be extremely useful in utilizing each others knowledge and talents to accomplish goals, but they may also come in handy at some point in the future. 3. Help UPUA do more As a student, you may not feel like your elected representatives are truly doing their job: representing your wants and needs. Gandhi once said: You must be the change you want to see in the world. What better way to do this than by working from the inside out? If you have gripes about how your student government is being run, chances are you are not alone. Idly complaining about what you feel is wrong can only go so far, why not take a risk and be proactive? Of course, if none of these reasons are persuading you enough, the many hours spent in the HUB will make you an expert in its layout, especially the upper floors.

One of the many benefits of attending a private or public school is the opportunity for students to make their

concerns and preferences known to the administration and student body through the democratic process, and governing body known as the school student council. A group of students who successfully run and obtain a seat on the student council can organize activities and charity events that are important to the students as well as lobby for school changes to the administration. If your child has expressed an interest in running for the school student council, there are several important points that should be considered. Does Your Child Have Time For This Added Activity? Holding a seat on the school student council requires time for meetings and student council sponsored activities. If your child is already balancing a heavy load of school work as well as a sports team and an after school club, running for a seat on the school student council could result in overload. While the passion for improving the atmosphere of the school is certainly an admirable one, your child may simply not have enough hours in the day to adequately fulfill all their responsibilities without letting one or more commitments suffer. Is Your Child Interested In Politics? Many politicians start their political careers by being involved with their school student councils. If your child is fascinated with the political process and is looking ahead to a career in local or state politics, then obtaining a position on the school student council can give them an up close and personal look at the democratic process in action. This experience can further whet their appetite for a career in politics and exemplify the difficulty in pleasing the masses as well as the powers that be Is Your Child Thick Skinned Enough To Deal With Losing? Unfortunately, politics is largely a popularity contest. This is never so true than regarding a school election. Although your child may have wonderful ideas and plans and be more than competent to serve on the school student council, he or she may lose their desired seat to a more popular or visible student. While losing the campaign for a seat on the school student council may provide a valuable learning and growth experience for your child, this may also be very detrimental to the very sensitive child. As long as your child is mentally and emotionally prepared for the possibility of losing the election, the process of campaigning for a seat on the student council may be beneficial to your child, no matter the outcome. Adequately preparing your child for the disappointment for losing the election may enable your child to develop a healthier and more balanced reaction to what they perceive as rejection and be a valuable experience. A seat on the school student council can offer your child a very beneficial experience as well as give them a nice extra curricular notation on their school records. While running for student council is a valuable experience by itself, it is not for every student. Hopefully, this article has helped you to decide whether to encourage your child to run for student council or steer them in another direction.

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Architectural Programming (Toa2)Document5 pagesArchitectural Programming (Toa2)Ryan Midel Rosales100% (1)

- Open Mind Elementary Unit 02 Grammar 2Document12 pagesOpen Mind Elementary Unit 02 Grammar 2khatuna sharashidzeNo ratings yet

- From Gerrit KischnerDocument6 pagesFrom Gerrit KischnerJulian A.No ratings yet

- Understanding The Concepts and Principles of Community ImmersionDocument25 pagesUnderstanding The Concepts and Principles of Community ImmersionJohn TacordaJrNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Strategic Decision Making, Phases inDocument22 pagesApproaches To Strategic Decision Making, Phases inShamseena Ebrahimkutty50% (8)

- Background of The Study FinalDocument8 pagesBackground of The Study FinalBIEN RUVIC MANERONo ratings yet

- Data Retreat 2016Document64 pagesData Retreat 2016api-272086107No ratings yet

- CGS20997626 (Hmef5023)Document15 pagesCGS20997626 (Hmef5023)Maizatul AqilahNo ratings yet

- Alfred Schutz, Thomas Luckmann, The Structures of Life-World v. 2Document353 pagesAlfred Schutz, Thomas Luckmann, The Structures of Life-World v. 2Marcia Benetti100% (2)

- Language 1 Module 3 Performance Task 1.1 (October 6 and 7 Day 1 and 2)Document18 pagesLanguage 1 Module 3 Performance Task 1.1 (October 6 and 7 Day 1 and 2)Jake Floyd G. FabianNo ratings yet

- CTPS - Thinking MemoryDocument24 pagesCTPS - Thinking MemoryGayethri Mani VannanNo ratings yet

- Largo, Johara D. FIDPDocument4 pagesLargo, Johara D. FIDPJohara LargoNo ratings yet

- Week 3 - Factors To Consider in Writing IMs (Ornstein), Principles of Materials DesignDocument4 pagesWeek 3 - Factors To Consider in Writing IMs (Ornstein), Principles of Materials DesignAlfeo Original100% (1)

- History of HighscopeDocument2 pagesHistory of Highscopelulwa1100% (1)

- Gapuz Review CenterDocument3 pagesGapuz Review CenterKyle CasanguanNo ratings yet

- Senior Management in Police Leadership Are Comprehensive of The Procedures, Regulations, and Customs Related To Policing Leadership DevelopmentDocument45 pagesSenior Management in Police Leadership Are Comprehensive of The Procedures, Regulations, and Customs Related To Policing Leadership DevelopmentInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Question: Compare Simon's Four-Phase Decision-Making Model To The Steps in Using GDSS AnswersDocument4 pagesQuestion: Compare Simon's Four-Phase Decision-Making Model To The Steps in Using GDSS AnswersDante MbaeNo ratings yet

- SCIENCE-3-COT 4th Quarter Science 2021Document3 pagesSCIENCE-3-COT 4th Quarter Science 2021Myralen Petinglay100% (19)

- Ucu 110 Project GuidelinesDocument5 pagesUcu 110 Project GuidelinesvivianNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - Q3 - ACP 10Document4 pagesWeek 2 - Q3 - ACP 10CherryNo ratings yet

- ED464521 2001-00-00 Organizational Culture and Institutional Transformation. ERIC DigestDocument8 pagesED464521 2001-00-00 Organizational Culture and Institutional Transformation. ERIC DigestreneNo ratings yet

- Notan Art Lesson For Kindergarten TeachersDocument19 pagesNotan Art Lesson For Kindergarten TeachersCikgu SuhaimiNo ratings yet

- OB Session Plan - 2023Document6 pagesOB Session Plan - 2023Rakesh BiswalNo ratings yet

- Course Guide PED 7Document5 pagesCourse Guide PED 7Torreja JonjiNo ratings yet

- A Study of Job Satisfaction Among Managers in Icici and HDFC Bank in JalandharDocument9 pagesA Study of Job Satisfaction Among Managers in Icici and HDFC Bank in JalandharAnkita kharatNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in General Chemistry 1Document4 pagesLesson Plan in General Chemistry 1Monique Joy ReyesNo ratings yet

- 12 Thadou Kuki MILDocument5 pages12 Thadou Kuki MILLun Kipgen0% (1)

- PGDT Clasroom Eng.Document107 pagesPGDT Clasroom Eng.Dinaol D Ayana100% (2)

- Work Ethics of The Proficient Teachers: Basis For A District Learning Action Cell (LAC) PlanDocument11 pagesWork Ethics of The Proficient Teachers: Basis For A District Learning Action Cell (LAC) PlanJohn Giles Jr.No ratings yet

- Art App Module 1Document35 pagesArt App Module 1jules200303No ratings yet