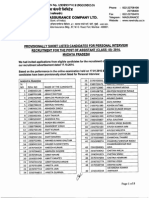

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

F M Dostoevsky

Uploaded by

At TanwiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

F M Dostoevsky

Uploaded by

At TanwiCopyright:

Available Formats

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

1879

Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky Born November 11, 1821 Moscow, Russian Empire

February 9, 1881 (aged 59) Died Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire

Occupation

Novelist, short story writer, essayist

Language

Russian

Nationality

Russian

Period

18461881

Notes from Underground Crime and Punishment Notable work(s) The Idiot The Brothers Karamazov Mariya Dmitriyevna Isayeva (185764) [her death] Spouse(s) Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina (18671881) [his death] Sofiya (1868), Lyubov (18691926), Children Fyodor (18751878)

Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky[1] (November 11, 1821 February 9, 1881[2]) was a Russian writer of novels, short stories and essays.[3] He is best known for his novels Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov. Dostoyevsky's literary works explored human psychology in the troubled political, social and spiritual context of 19th-century Russian society. Considered by many as a founder or precursor of 20th-century existentialism, Dostoyevsky wrote, with the embittered voice of the anonymous "underground man", Notes from Underground (1864), which was called the "best overture for existentialism ever written" by Walter Kaufmann.[4] Dostoyevsky is often acknowledged by critics as one of the greatest and most prominent psychologists in world literature.[5] Biography Dostoyevsky was born in Moscow, the second of seven children born to Mikhail and Maria Dostoyevsky.[6] Dostoyevsky's father Mikhail was a doctor and a devout Christian, who practiced at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in Moscow. The family lived in a small apartment in the hospital grounds, and it wasn't until he was 16 years old, that Dostoyevsky moved to St Petersburg to attend a Military Engineering Institute. The hospital was located in one of the city's worst areas; local landmarks included a cemetery for criminals, a lunatic asylum, and an orphanage for abandoned infants. This urban landscape made a lasting impression on the young Dostoyevsky, whose interest in and compassion for the poor, oppressed and tormented was apparent in his life and works. Although it was forbidden by his parents, Dostoyevsky liked to wander out to the hospital garden, where the patients sat to catch a glimpse of the sun. The young Dostoyevsky appreciated spending time with these patients and listening to their stories. There are many stories of Dostoyevsky's father's despotic treatment of his children, but this despotism was tempered by his extreme care for his children and their upbringing. After returning home from work, he would take a nap while his children, ordered to keep absolutely silent, stood by their slumbering father in shifts and swatted the flies that came near his head. But the father was also careful to send his children to private schools where they would not be beaten. In the opinion of Joseph Frank, author of a definitive biography of Dostoyevsky, the father figure in The Brothers Karamazov is not based on Dostoyevsky's own father. Letters and personal accounts demonstrate that they did have a fairly loving relationship.

The young Dostoyevsky, in an 1847 portrait by Trutovsky In 1837, shortly after his mother died of tuberculosis, Dostoyevsky and his brother were sent to St Petersburg to attend the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute, nowadays called the Military Engineering-Technical University.[7] Fyodor's father died in 1839. Though it has never been proven, it is believed by some that he was murdered by his own serfs.[8] According to one account, the serfs became enraged during one of his drunken fits of violence, and after restraining him, poured vodka into his mouth until he drowned. A similar account appears in Notes from Underground. Another story holds that Mikhail died of natural causes, and a neighboring landowner invented the story of his murder so that he could buy the estate at a cheaper price. Some, like Sigmund Freud in his 1928 article, "Dostoevsky and Parricide", have argued that his father's personality had influenced the character of Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, the "wicked and sentimental buffoon", father of the main characters in his 1880 novel The Brothers Karamazov, but such claims fail to withstand the scrutiny of many critics[who?]. Dostoyevsky suffered from epilepsy and his first seizure occurred when he was nine years old.[9] Epileptic seizures recurred sporadically throughout his life, and Dostoyevsky's experiences are thought[10] to have formed the basis for his description of Prince Myshkin's epilepsy in his novel The Idiot and that of Smerdyakov in The Brothers Karamazov, among others. At the Saint Petersburg Institute of Military Engineering[11] Dostoyevsky was taught mathematics, a subject he despised. However, he also studied literature by Shakespeare, Pascal, Victor Hugo and E.T.A. Hoffmann. Though he focused on areas different from mathematics, he did well in the exams and received a commission in 1841. That year, influenced by the German poet/playwright Friedrich Schiller, he wrote two romantic plays: Mary Stuart and Boris Godunov. The plays have not been preserved. Dostoyevsky described himself as a "dreamer" when he was a young man. He also revered Schiller at that age. However, in the years during which he wrote his great masterpieces, his opinions changed and he sometimes made fun of Schiller. Dostoyevsky was made a lieutenant in 1842, and left the Engineering Academy the following year. He completed a translation into Russian of Balzac's novel Eugnie Grandet in 1843, but it brought him little to no attention. Dostoyevsky started to write his own fiction in late 1844 after leaving the army. In 1846, his first work, the epistolary short novel, Poor Folk, printed in the almanac A Petersburg Collection (published by N. Nekrasov), was met with great acclaim. As legend has it, the editor of the magazine, poet Nikolai Nekrasov, walked into the office of liberal critic Vissarion Belinsky and announced, "A new Gogol has arisen!" Belinsky, his followers, and many others agreed. After the novel was fully published in book form at the beginning of the next year, Dostoyevsky became a literary celebrity at the age of 24. In 1846, Belinsky and many others reacted negatively to his novella, The Double, a psychological study of a bureaucrat whose alter ego overtakes his life. Dostoyevsky's fame began to fade. Much of his work after Poor Folk received ambivalent reviews and it seemed that Belinsky's prediction that Dostoyevsky would be one of the greatest writers of Russia was mistaken. Death Dostoyevsky died in St. Petersburg on 9 February [O.S. 28 January] 1881 of a lung hemorrhage associated with emphysema and an epileptic seizure. A copy of the New Testament Bible given to him in Siberia sat on his lap. He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg. Forty thousand mourners attended his funeral.[23] His tombstone reads; Verily, Verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. (Excerpt from John 12:24, which is also the epigraph of his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov.) The rented apartment where he died and spent the last few years of his life is where he wrote his final novel The Brothers Karamazov. The apartment, situated in a building at 5 Kuznechnyi pereulok, has been restored with old

photographs to how it looked when he lived there. It opened in 1971 as the Dostoyevsky House Museum and is a popular tourist attraction in the city.[24] Influence

Portrait of Dostoyevsky in 1872 painted by Vasily Perov. Some, like journalist Otto Friedrich,[25] consider Dostoyevsky to be one of Europe's major novelists, while others like Vladimir Nabokov maintain that from a point of view of enduring art and individual genius, he is a rather mediocre writer who produced wastelands of literary platitudes.[26] Dostoyevsky promoted in his novels religious moralities, particularly those of Eastern Orthodox Christianity.[5] Indeed, "Dostoyevsky and the Religion of Suffering," the essay devoted to Dostoyevsky in Eugne-Melchior de Vog's Le roman russe (1886), is widely considered to be the most influential early analysis of the novelist's work, introducing Dostoyevsky and other Russian novelists to the West. Nabokov argued in his University courses at Cornell, that such religious propaganda, rather than artistic qualities, was the main reason Dostoyevsky was praised and regarded as a 'Prophet' in Soviet Russia.[27][clarification needed] James Joyce and Virginia Woolf praised his prose. Ernest Hemingway cited Dostoyevsky as a major influence on his work, in his posthumous collection of sketches A Moveable Feast. In a book of interviews with Arthur Power (Conversations with James Joyce), Joyce praised Dostoyevsky's prose: ...he is the man more than any other who has created modern prose, and intensified it to its present-day pitch. It was his explosive power which shattered the Victorian novel with its simpering maidens and ordered commonplaces; books which were without imagination or violence. In her essay The Russian Point of View, Virginia Woolf said: The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools, gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil and suck us in. They are composed purely and wholly of the stuff of the soul. Against our wills we are drawn in, whirled round, blinded, suffocated, and at the same time filled with a giddy rapture. Out of Shakespeare there is no more exciting reading.[28] Dostoyevsky monument at the Russian State Library in Moscow. Dostoyevsky displayed a nuanced understanding of human psychology in his major works. He created an opus of vitality and almost hypnotic power, characterized by feverishly dramatized scenes where his characters are frequently in scandalous and explosive atmospheres, passionately engaged in Socratic dialogues. The quest for God, the problem of evil and suffering of the innocents haunt the majority of his novels. His characters fall into a few distinct categories: humble and self-effacing Christians (Prince Myshkin, Sonya Marmeladova, Alyosha Karamazov, Saint Ambrose of Optina), self-destructive nihilists (Svidrigailov, Smerdyakov, Stavrogin, the underground man)[citation needed], cynical debauchees (Fyodor Karamazov, Dmitri Karamazov), and rebellious intellectuals (Raskolnikov, Ivan Karamazov, Ippolit); also, his characters are driven by ideas rather than by ordinary biological or social imperatives. In comparison with Tolstoy, whose characters are realistic, the characters of Dostoyevsky are usually more symbolic of the ideas they represent, thus Dostoyevsky is often cited as one of the forerunners of Literary Symbolism, especially Russian Symbolism (see Alexander Blok).[29] Dostoyevsky statue, erected 1918, in front of Mariinsky Hospital, the writer's birthplace in Moscow. Dostoyevsky's novels are compressed in time (many cover only a few days) and this enables him to get rid of one of the dominant traits of realist prose, the corrosion of human life in the process of the time flux; his characters primarily embody spiritual values, and these are, by definition, timeless. Other themes include suicide, wounded

pride, collapsed family values, spiritual regeneration through suffering, rejection of the West and affirmation of the Russian Orthodox Church and of tsarism. Literary scholars such as Mikhail Bakhtin have characterized his work as "polyphonic": Dostoyevsky does not appear to aim for a "single vision", and beyond simply describing situations from various angles, Dostoyevsky engendered fully dramatic novels of ideas where conflicting views and characters are left to develop unevenly into unbearable crescendo. Dostoyevsky and the other giant of late 19th century Russian literature, Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, never met in person, even though each praised, criticized, and influenced the other (Dostoyevsky remarked of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina that it was a "flawless work of art"; Henri Troyat reports that Tolstoy once remarked of Crime and Punishment that, "Once you read the first few chapters you know pretty much how the novel will end up").[citation needed] There was a meeting arranged, but there was a confusion about where the meeting was to take place and they never rescheduled. Tolstoy wept when he learned of Dostoyevsky's death.[30] A copy of The Brothers Karamazov was found on the nightstand next to Tolstoy's deathbed at the Astapovo railway station. Novels and novellas y y y y y y y y y y y y y y y Poor Folk ( [Bednye lyudi], 1846) The Double: A Petersburg Poem ( : [Dvoynik: Peterburgskaya poema], 1846) Netochka Nezvanova ( [Netochka Nezvanova], 1849) Uncle's Dream ( [Dyadyushkin son], 1859) The Village of Stepanchikovo ( [Selo Stepanchikovo i ego obitateli], 1859) Humiliated and Insulted ( [Unizhennye i oskorblennye], 1861) The House of the Dead ( [Zapiski iz mertvogo doma], 1862) Notes from Underground ( [Zapiski iz podpolya], 1864) Crime and Punishment ( [Prestuplenie i nakazanie], 1866) The Gambler ( [Igrok], 1867) The Idiot ( [Idiot], 1869). Translated into English by Henry Carlisle and Olga Carlisle. The Eternal Husband ( [Vechnyj muzh], 1870) Demons ( [Besy], 1872) The Adolescent ( [Podrostok], 1875) The Brothers Karamazov ( [Brat'ya Karamazovy], 1880)

[edit] Short stories y y y y y y y y y y y y y " ["Gospodin Prokharchin"], 1846) "Mr. Prokharchin" (" "Novel in Nine Letters" (" " ["Roman v devyati pis'mah"], 1847) "The Landlady" (" " ["Hozyajka"], 1847) "The Jealous Husband" (" " ["Chuzhaya zhena i muzh pod krovat'yu"], 1848) "A Weak Heart" (" " ["Slaboe serdze"], 1848) "Polzunkov" (" " ["Polzunkov"], 1848) "The Honest Thief" (" " ["Chestnyj vor"], 1848) "The Christmas Tree and a Wedding" (" " ["Elka i svad'ba"], 1848) "White Nights" (" " ["Belye nochi"], 1848) "A Little Hero" (" " ["Malen'kij geroj"], 1849) "A Nasty Anecdote" (" " ["Skvernyj anekdot"], 1862) " ["Krokodil"], 1865) "The Crocodile" (" "Bobok" (" " ["Bobok"], 1873)

You might also like

- Waves On A StringDocument12 pagesWaves On A StringAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Madhya PradeshDocument5 pagesMadhya PradeshAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Jnana Vahini InteractiveDocument53 pagesJnana Vahini InteractiveAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Divine Teachings of Kriya Yoga Master Paramahamsa Hariharananda GiriDocument4 pagesDivine Teachings of Kriya Yoga Master Paramahamsa Hariharananda GiriAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Parāśara Jyoti A: Devaguru B Haspati CenterDocument6 pagesParāśara Jyoti A: Devaguru B Haspati CenterGovardhan PanatiNo ratings yet

- Wave Optics Part IDocument62 pagesWave Optics Part IAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- JEE Mains Sample PaperDocument5 pagesJEE Mains Sample PaperAt Tanwi100% (1)

- Negotiable InstrumentsDocument11 pagesNegotiable InstrumentsMahesh ChavanNo ratings yet

- Top 100 Quant Tips and Tricks by IIMDocument14 pagesTop 100 Quant Tips and Tricks by IIMAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Physics Practice TestDocument2 pagesPhysics Practice TestAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Chapters 0 and 1Document29 pagesChapters 0 and 1Tulus PramujiNo ratings yet

- Collection of Job Interview Questions and The AnswersDocument46 pagesCollection of Job Interview Questions and The AnswersctansariNo ratings yet

- EllipseDocument2 pagesEllipseAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Maths Concepts and Formulae: y FX F y XDocument16 pagesMaths Concepts and Formulae: y FX F y XAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Physics Key Points and FormulaeDocument35 pagesPhysics Key Points and FormulaeAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- CircleDocument4 pagesCircleAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Physics 3Document9 pagesPhysics 3At TanwiNo ratings yet

- T KSFR"KH N'F"V Esa Osokfgd LQ (K: Ys (KD% Psru Dqekj LksuhDocument8 pagesT KSFR"KH N'F"V Esa Osokfgd LQ (K: Ys (KD% Psru Dqekj LksuhprasannandaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry FinalDocument27 pagesChemistry FinalAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- 27 Nakshatra PadasDocument13 pages27 Nakshatra PadasAstrologer in Dubai Call 0586846501No ratings yet

- Pañcāk Arī InitiationDocument19 pagesPañcāk Arī InitiationAt Tanwi100% (1)

- Intercepted Signs in Horoscopes A New Concept B WDocument15 pagesIntercepted Signs in Horoscopes A New Concept B WAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Problems For 9Document1 pageProblems For 9At TanwiNo ratings yet

- Shiv MahapuranaDocument43 pagesShiv MahapuranaAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Review Test II: Course Name: QUARKDocument1 pageReview Test II: Course Name: QUARKAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Corrected Page Physics SheetDocument2 pagesCorrected Page Physics SheetAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Students Must ReadDocument1 pageStudents Must ReadAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Problems in IsomerismDocument5 pagesProblems in IsomerismAt Tanwi100% (1)

- ChemLab - Chemistry 6 - Spectrum of The Hydrogen Atom - Chemistry & BackgroundDocument13 pagesChemLab - Chemistry 6 - Spectrum of The Hydrogen Atom - Chemistry & BackgroundAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- FunctionsDocument5 pagesFunctionsAt TanwiNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Demons by DostoyevskiDocument10 pagesThe Demons by DostoyevskijohnchoilcNo ratings yet

- Dostoevsky in Moderation - Thomas MannDocument8 pagesDostoevsky in Moderation - Thomas MannNyetochka100% (3)

- The 100 Best Books of All TimeDocument8 pagesThe 100 Best Books of All Timepmag11100% (1)

- PGB 1 - Parte IiDocument27 pagesPGB 1 - Parte Iikira1234No ratings yet

- The Mystery of Suffering - The Philosophy of Dostoevskys CharacteDocument49 pagesThe Mystery of Suffering - The Philosophy of Dostoevskys CharacteDinoNo ratings yet

- CamusDocument437 pagesCamus2371964100% (2)

- African American WritersDocument34 pagesAfrican American WritersDavi Silistino de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Dostoevsky - A Revolutionary ConservativeDocument7 pagesDostoevsky - A Revolutionary ConservativeMalgrin2012No ratings yet

- Crime and PunishmentDocument311 pagesCrime and PunishmentSolomon Tamara83% (6)

- Eternal Husband Dostoevsky PDFDocument2 pagesEternal Husband Dostoevsky PDFScottNo ratings yet

- Fyodor Dostoevsky's Notes From The Underground A Reading in Light of Marxist and Psychoanalytic TheoriesDocument14 pagesFyodor Dostoevsky's Notes From The Underground A Reading in Light of Marxist and Psychoanalytic TheoriesMina Wagih WardakhanNo ratings yet

- Pope Francis A Big Fan of Mozart, Dostoevsky, and CervantesDocument2 pagesPope Francis A Big Fan of Mozart, Dostoevsky, and Cervantescbacavis1786No ratings yet

- Both Fyodor Dostoevsky and Emily Bronte perceive moral transgression as an escape from conventional Christian ideals in search of a higher reality, in their respective novels Crime and Punishment and Wuthering Heights. To what extent do you agree with this statement?Document7 pagesBoth Fyodor Dostoevsky and Emily Bronte perceive moral transgression as an escape from conventional Christian ideals in search of a higher reality, in their respective novels Crime and Punishment and Wuthering Heights. To what extent do you agree with this statement?Moses TanNo ratings yet

- Raskolnikov - Dostoevsky's Hegelian AgentDocument17 pagesRaskolnikov - Dostoevsky's Hegelian Agentibis8No ratings yet

- Lawlan, Rachel - Confession and Double Thoughts - Tolstoy, Rousseau, Dostoevsky PDFDocument27 pagesLawlan, Rachel - Confession and Double Thoughts - Tolstoy, Rousseau, Dostoevsky PDFfluxosNo ratings yet

- The Idiot StudyguideDocument46 pagesThe Idiot StudyguideDinoNo ratings yet

- Topic Research Proposal Objectives:: Crime and Punishment As A Psychological NovelDocument7 pagesTopic Research Proposal Objectives:: Crime and Punishment As A Psychological NovelSharifMahmud50% (2)

- The Imagination and The "I" in Zamjatin's WeDocument13 pagesThe Imagination and The "I" in Zamjatin's WeInbal ReshefNo ratings yet

- Notes From Underground - Dostoevsky SDocument7 pagesNotes From Underground - Dostoevsky SratiguanaNo ratings yet

- DostoevskyDocument2 pagesDostoevskyapi-276757735No ratings yet

- Berlin - Russia and 1848Document21 pagesBerlin - Russia and 1848Joel CruzNo ratings yet

- PoemsDocument33 pagesPoemsbonkyoNo ratings yet

- The Brothers KaramazovDocument8 pagesThe Brothers KaramazovAnonymous sao1siUbNo ratings yet

- CapDocument7 pagesCapMelynJoySiohanNo ratings yet

- Dostoyevsky Crime and PunishmentDocument452 pagesDostoyevsky Crime and PunishmentEl SheikhNo ratings yet

- Christ and Punishment: The Subtext Behind Dostoevsky's Biblical ParallelsDocument11 pagesChrist and Punishment: The Subtext Behind Dostoevsky's Biblical ParallelsConnor BremNo ratings yet

- Muharem Bazdulj The Second BookDocument154 pagesMuharem Bazdulj The Second BookIna Ch0% (1)

- Wisdom From Above?Document16 pagesWisdom From Above?akimelNo ratings yet

- Svetlana BoymDocument35 pagesSvetlana BoymPragya PAramita100% (1)