Professional Documents

Culture Documents

RBNZ PC Housing Submission

Uploaded by

leithvanonselenOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

RBNZ PC Housing Submission

Uploaded by

leithvanonselenCopyright:

Available Formats

SubmissiontotheProductivityCommissionInquiryon HousingAffordability ReserveBankofNewZealand August2011 ExecutiveSummary ChangesinhousepricesmatterfortheReserveBankofNewZealand(theBank),boththroughtheir cyclicalimplicationsformonetarypolicyandthelongertermimplicationsofthelevelofhouseprices formacroeconomicandfinancialstability. Demandforhousingcanchange,attimesquitequickly,and,asinanymarket,itisimportantthat thesupplyofhousesquicklyrespondstochangesindemand.Supplyresponsemoderatespotentially damagingswingsinhouseprices.

ces.Policycanhaveaninfluenceonhousingmarketoutcomesthrough a variety of channels, in particular over the longerterm, by helping ensure that the regulatory regimefacilitatesthereadyadjustmentofsupplytodemand. LessonscancertainlybelearntfromexaminingNewZealandsmostrecenthousingcycle,which is probablythemostmarkedinourmodernhistory.Butpolicydevelopmentshouldbeinformednot justbythelastcyclebutalsobypreviousepisodesinNewZealandshistoryandbytherichnessof international experience. What matters most is getting longrun policy prescriptions right and this requireslearningfromawidevarietyofsourcesratherthanfromanysingleepisode.Therightpolicy framework should probably be focused on supply conditions in the housing market, although a sensibletaxstructureisalsolikelytomatter. NewZealandhasprobablyhadtoofewhouses,comingtomarkettooslowly.Theusualconclusion when the real price of a good has trended upwards is that supply has lagged demand. Research evidence suggests that residential construction has been relatively responsive to rises in house prices(atleastrelativetoOECDnorms).Residentialconstructionis,however,alsoverysensitiveto increases in construction costs. This has inhibited the construction of new homes. Over the last decade,thecostofconstructionofnewhomesinNewZealandhasrisensubstantiallymorethanthe generalincreaseinthecostsofgoodsandservices. Supply constraints matter a lot for determining housing market outcomes (see Glaeser et al 2007 and Huang and Tang 2010). This is particularly so for countries or regions with fast growing populations,likeNewZealand.Inthelongrun,evidencesuggeststhatsignificantsupplyconstraints leadbothtobiggerhousepriceboomsandeventuallytonastierhousepricecorrections. ManyotherfactorshaveinfluencedhousepricecyclesinNewZealand.Bigswingsinmigration(by OECDstandards)havebeenanimportantfactor.Atthemargins,changesinrelevanttaxparameters, as well as the stance of monetary policy, will have been important at times. With housing supply slow to adjust, these were among the factors that helped trigger initial increases in house prices. Higherpricesinturnfuelledexpectationsoffurtherappreciation,whichservedtoreinforcedemand forhousingatevenhigherprices. As the Reserve Bank has acknowledged previously, with the benefit of hindsight, monetary policy mayhavebeentooslowtotightenintheearlystagesofpreviousbusinesscycles.Rapidgrowthin fiscaltransferslateinthecycleprobablyalsoprovidedaboosttoincomethatsustainedthehouse price boom a little longer than otherwise might have been possible. Both these mattered more than they should have because of the way demand shocks and supply constraints interacted to triggerthehousepriceboominthefirstplace.

Policy should focus on regulation that gets supply conditions in the housing market right and removesbarriersthatimpedeproductivitygainsintheconstructionsector.Suchapolicyframework should produce lower, and perhaps most importantly from the Banks perspective, less variable housepricesoverthelongrun.Wearenotexpertsinthedetailsofhousingsupplyissues,butwe wouldencouragetheCommissiontofocusonwaystoputinplacearegulatoryenvironmentthat(i) enhances productivity in the residential construction sector; (ii) supports land availability; and (iii) promotesaresidentialconstructionsectorthatisresponsivetopricesignals. Taxation regimes can affect house price movements and house price cycles, but our judgement is that they have not been of decisive importance compared to supply factors, migration factors or fiscal and monetary policy. At times, tax provisions, in conjunction with other shocks, may have served to amplify or extend a housing boom that had initially been triggered by quite unrelated factors.Ourreadingoftheinternationalliteraturesuggeststhatthepresenceorabsenceofacapital gainstaxisnotadecisivefactorexplaininghousepricebehaviourhereorinothercountries. The liberalisation of access to finance since the 1980s will have had a significant impact on debt levels, as well as the distribution of debt. Of course, the typical interest rate in New Zealand has beenrelativelyhighcomparedtointernationalstandards.Overthelongerterm,changesinaccessto financeshouldnothavealargeorsustainedeffectonhouseprices.Theabilitytouseadditionalland for housing (or use existing land more intensively) and the value of that land in alternative uses, probablymattermost.Overlongperiods,andallowingforproductivitygrowth,thepricesofother inputstohousingconstructionlikewood,steelandofcourseunitlabourcosts,shouldprobablynot growmuchdifferentlythanthegenerallevelofpricesintheeconomy. In a secondbest world where supply issues remain intractable, limiting excess demand pressures, whichcancomefromunexpectedswingsinpopulationgrowththroughchannelssuchasmigration inflows,couldmitigatebigswingsinhouseprices.Implementationlagswouldposechallenges,but moregenerally,thisissuehelpshighlightthescopeforbettercoordinationofgovernmentpolicies thataffecthousingsupplyanddemand. Lowermaximummarginaltaxratesonpersonalincomehavereducedthebenefitavailabletothose (includingownersofrentalhousing)abletodeductinterestagainstothertaxableincome.Inflation indexing the tax treatment of interest (something the Reserve bank has long advocated) would furtherreducethosebenefits,eliminateadistortionintheincometaxsystem,andhaveincidental benefitsforthehousingmarket.Amoreappropriatetaxtreatmentoftheinflationwouldprobably largelyeliminatereportedtaxlossesonresidentialrentalpropertiesevennearthepeaksofhousing booms(whenrentalyieldstendtobelowest).

Introduction The Reserve Bank welcomes the opportunity to make this brief submission to the Productivity Commissionsinquiryintohousingaffordability.Thissubmissionshouldbereadtogetherwiththe widerangeofdataillustratedintheCommissionsissuespaper. The guidance laid out in the Housing Issues paper from the Productivity Commission cuts across many dimensions. Here, we examine the housing market in aggregate, focusing on demand and supplyfactors.WedonotaddresstheimpactofhousingaffordabilityissuesonlowerincomeNew Zealanders, nor do weexplore importantregionalhousing issues.Such issues aretypicallybeyond thescopetheReserveBanksexpertise. Inourjudgement,theresponsivenessofthesupplyofnewhousesisacriticalfactorbehindhouse priceswhenhousingdemandshifts. HousepricesandtheReserveBankofNewZealand The Reserve Bank has statutory responsibilities that span monetary policy, financial stability and prudential supervision. Given the way that the New Zealand housing market has behaved, understandingthehousingmarketisessentialforcarryingoutourresponsibilities.TheReserveBank has commented on issues that relate to housing in its submissions to the Commerce Select Committee(2007),theFinanceandExpenditureCommittee(2007)andtheSavingsWorkingGroup (2010). The Reserve Banks responsibilities relate to house prices in two important ways: (i) the cyclical movements in house prices over the short to mediumterm and the way they influence demandandmonetarypolicy;and(ii)changes inthe levelofhouse pricesthataffectthevalueof mortgagecollateralandcould,undercertainstressedconditions,poseissuesforfinancialstability. Large swings in house prices over the cycle matter primarily to the extent that they change consumption behaviour, by easing collateral constraints or leading households to think that their real wealth has increased. The associated wealth effects can bring forward consumption (see De Veirman and Dunstan (2008) and Smith (2010)), residential investment decisions and drive up inflation(asfirmsincreasetheiroutputpriceinresponsetostrongerdemand).1ManyoftheReserve Banks Monetary Policy Statements have documented the impact of movements in New Zealand housepricesontheeconomyandmonetarypolicy.Ifanything,theseeffectsseemtohavebeena littlestrongerinNewZealandthaninsomeotheradvancedcountries. Housepricesswingscanoftenbecostly.Theycandistorttheallocationofresources,detractfrom economic efficiency and, at times, threaten financial stability. Moreover, as figure 1 illustrates for theUnitedStates,overaverylongperiodoftime,realhousepricestendtobestablearoundavery modestgrowthratetheswingsinrealpricesdominateanytrendmovement. Largerisesinthelevelofhousepricesarealsooftenassociatedwithincreasedhouseholdleverage. If those higher prices prove unsustainable, the resulting fall in house prices can generate financial stabilityrisks(asrecentlyhappenedintheUnitedStatesandIreland)or,atleast,actasasustained drag on private demand and economic activity (as appears to be the case in a number of other advancedeconomiesatpresent).

1

Movementsinhousepricescanbereflectiveofshockstootherpartsoftheeconomy,suchasthosefromcommoditypricesbooms.De VeirmanandDunstan(2008,2011),forexample,exploredifferencesbetweenshockstofinancialwealthandshockstohousingwealth.

Figure1:LongtermrealhousepricesintheUS

200 180 160 140

Index

120 100 80 60 40 20 0 1880

1900

1920

1940

1960

1980

2000

2020

Source:RobertShillerasusedinIrrationalExuberance(2000).Updatedquarterly.

Appropriatefocusfortheinquiry Turning to the inquiry into housing affordability, we think the focus should be on the longterm structural issues. We also think the inquiry should be careful not to overweight the most recent cycleinhouseprices.ThisisbecausetheincreaseinrealhousepricesinNewZealandpredatesthe latestboom,incontrasttotheUnitedStatesandsomeothercountrieswhichhadrelativelystable andflathousepricesupuntilaround1997. Butitcanbedifficulttoidentifyanddistiltheappropriatepolicyresponsetolongrunissues.New Zealands previous housing cycles and crosscountry evidence are useful in this regard. Although data issues can distort comparisons, crosscountry evidence might help shed light on the possible roleofinflation,financialliberalisationandtaxpolicyand,morebroadly,onwhatcanrealisticallybe achievedintheareaofhousingpolicy. Thedemandside When supply is relatively constrained in the shortterm, swings in demand matter a lot for the determination of house prices. Lots of factors influence changes in the demand for housing but factors such as migration and demography appear to have been particularly important in New Zealand. The Reserve Bank has noted the impact of migration on, not just the previous housing cycle, but also those of the 1970s and the 1990s (see our submission to the Commerce select committee2007,forexample).Indeed,NewZealandhastendedtohavelargeswingsinmigration flows.Moreover,the responseofhousepricestomigrationappears largerelativetointernational experience.ColemanandLandonLane(2007)estimatethathousepricesrise10percentinresponse to an increase in migration equivalent to one percent of the population. Of course, net migration flows are,atleast in part,an endogenousresponsetochangesintheunderlyingbehaviourof the economy.Butinspiteofthedifficultiesinidentifyingtherelativecontributionofdifferentfactors,it

isimportantthattheimplicationsofbigswingsinthepopulationgrowthrateforhouseprices,and macrostabilitymoregenerally,arerecognised. Anotherdemandsidefactorinthelatestcyclewasrapidgrowthinfiscaltransferslateinthecycle, targetedatgroupswhowereprobablyamongthosepurchasinghouseswithlargemortgages.These transfers probably provided the income to sustain the house price boom a bit longer than would haveotherwisebeenpossible.Generally,wethinklessprocyclicalityinfiscalpolicyhelps. And expectations dynamics in housing markets matter. While supply was initially slow to respond sufficientlystronglytoincreaseddemand,totalresidentialinvestmentasapercentageofGDPended upbeingquitesimilartothatinothercountrieswithsimilarpopulationgrowth(includingtheUnited States)acrosstheboomperiodasawhole.Butfacedwithlargedemandshockssupplyappearsto have been slow to respond. This allowed prices to rise quite materially, which appeared to fuel expectationsofongoingfuturehousepricerises.Itisreasonablywellacceptedthatexpectationsof future house prices are weakly anchored and hence quite easily displaced. The prevalence of publicationstoutingtheattractivenessofrentalpropertyasaninvestmentoptionincreasedasthe boomwenton,notdecreased. Monetary policy can also play a role.If interest rates are set too low for too long, that will affect demand for housing and house prices. As we noted in our 2007 submission to the Finance and Expenditure Committee, with hindsight we may have been too slow to tighten monetary policy againstabackdropofarelativelystrongeconomicperformance.Intermsofcyclicaldemand,wecan certainlyleanagainstthe windregarding assetprices,andleaningearlyisbetterthanleaning late (seeBollard2004,formorediscussion).Internationally,inthewakeoftheeventsofthelastdecade, some central banks that had held to the hypothesis that asset price bubbles are too difficult to identify and that a central bank should simply mop up the mess after the bubble has burst, have shifted their ground. That said, preemptive moves to try to manage house price booms using monetarypolicyriskexacerbating stressesonthetradablesectoroftheeconomy.Raisinginterest ratesinthiscontextwillincreasedemandforNewZealanddollardenominatedassets,increasingthe exchange rate and putting pressure on the bottom line of both exporters and importcompeting manufacturers. It would be preferable to have the sort of housing market that was less prone to exaggeratedpricefluctuationsinthefirstplace. Followingthefinancialcrisis,therehasbeenconsiderableinternationalinterestinthepossiblerole of various macroprudential instruments in helping to manage the consequences of credit cycles. Macroprudentialinstrumentsarevariousprudentialrequirementsplacedonthebalancesheetsof banks or other financial institutions. The objective of these tools would be to promote greater financial system resilience in the face of the credit cycle, or perhaps, rather more ambitiously, to directly leanagainstthecreditcycle. Whilemanyofthesetools are broadinfocus,therehasalso been interest in some instruments that would directly relate to housing lending such as administrativerestrictionsonmaximumloantovalueratios.Thislatterinstrumenthasbeenwidely employedthroughoutAsiaandhasbeenadoptedmorerecentlyinCanada,andinsomeEuropean countries. However, there is as yet limited experience with these tools in a developed country context. The Reserve Banks work suggests that macroprudential instruments could possibly have a role to playinhelpingmanagethecreditcycle,althoughtheirinfluenceislikelytobeatthemarginandto date remains largely untested. While the international research is continuing, such tools are generally seen as best directed toward bolstering financial system resilience in the face of credit growth being used rather than to directly influence the growth in credit or asset prices. The

possibility of using such instruments in the future should not replace a continued focus on the underlyingdriversofhouseprices,particularlyhousingsupplyconstraints. Thesupplyside Itisnowwellestablishedintheinternationalliteraturethatdifferenthousingsupplyregimesgoa long way to explaining differences in cyclical house price behaviour (see Glaeser et al 2007 and Glaeser and Ward 2009, for example). These effects are particularly important in countries or regionswherepopulationsaregrowingcomparativelyrapidly.Thereisstrongevidenceofthisinthe UnitedStatesatboththestateandcountylevel(seeHuangandTang2010).Whendemandforany productispronetosignificantchanges,itisespeciallyimportantthatsupplycanrespondrelatively quickly. The Reserve Bank is not an expert on the microeconomics of regulation of the housing and constructionmarket.However,ourinterpretationofworkbyArthurGrimesandothers(seeGrimes andAitken2006andGrimesandLiang2007,forexample)andtherecentseriesofOECDpapers(see CalderaandJohansson2010,the2011OECDSurveyofNewZealandandCheung2011)isthatthe importance of regulatory regimes applies with force to New Zealand. The OECD work shows that while New Zealands residential construction is relatively responsive to house prices (figure 2), investmentintheresidentialcapitalstockisparticularlysensitivetoincreasesinconstructioncosts (figure3)thatinhibitthesupplyresponse.

Figure2:OECDEstimatesoflongrunhousingsupplyresponsetoprices

2.0

Estimates of the long-run price-elasticity of new housing supply

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

JPN

FIN

SWE

NLD

DEU

ESP

FRA

NOR

CAN

BEL

CHE

AUT

NZL

ISR

DNK

POL

ITA

AUS

IRL

GBR

USA

Source:SnchezandJohansson(2011).Alargernumberindicatesamoreresponsivesupply.

Overall,thatseemstomeanthatourhousingsupplyhasnotbeenveryresponsivewhentherehave beenbigswingsinhousingdemand.Asaresult,oninternationalmetrics,ourhousepriceslookhigh, andhaveincreasedverysubstantiallyinthelastdecade.Supplyconstraintsarethereforeakeyarea warranting policy attention (see RBNZ submission to the Commerce Committee 2007 and Cheung 2011).

Figure3:OECDEstimatesoflongrunhousingsupplyresponsetoconstructioncosts

3

Estimates of the long-run price-elasticity of new housing supply

-1

-2

-3

-4

ISR

IRL

ITA

GBR

SWE

DEU

CAN

CHE

DNK

NOR

USA

AUS

JPN

FIN

NLD

ESP

FRA

BEL

NZL

AUT

POL

Source:SnchezandJohansson(2011).Alargernumberindicatesamoreresponsivesupply.

The key supply factors appear to be the availability and price of land for residential purposes and constructioncosts.TheResourceManagementAct,andthewayitisappliedbylocalcouncils,may be playing a role. One solution that is often advanced regarding land prices is for metropolitan planningagenciestoeasetheirurbanlimits and,moregenerally,toensurethatresidentialzoning practicesaremoredirectlyresponsivetomarketpricesignals.Thiswillhelpensurethatlandisused forthemosteconomicallyvaluablepurposes,asrevealedbyprices.Issueshavealsobeenraised around the most appropriate way for local council to cover the infrastructure costs around new housing,andwhetherthemovetogreaterlumpsumdevelopmentleviesmayhaveplayedarolein inadvertentlyexaggeratinghousepricefluctuations. Regarding construction costs, figure 4 shows that the CPI subindex for construction has risen by much more than the index for all consumer products, while the increase in hourly wages for construction workers since 2000 has been only slightly higher than for the full workforce. This is suggestiveoflowlabourproductivitygrowthinconstructionrelativetotherestoftheeconomy(and NewZealandslabourproductivityhasnotbeenhighintherestoftheeconomyeither).2Overthe very longterm, and allowing for productivity growth, the prices of other inputs to housing constructionlikewood,steelandofcourseunitlabourcosts,shouldprobablygrowinlinewiththe generallevelofpricesintheeconomy. Some reasons for this productivity differential probably include the lack of scale in dwelling construction,withmanydwellingsbeingbuiltasoneoffs,largelytoindividualspecifications.Alack ofinnovationinconstructionmethodsmaybeanotherproblem.Whileitisnotcleartowhatextent the poor productivity performance of the construction sector reflects regulatory constraints, we nonethelessencouragetheCommissiontolookcarefullyatthisissue.

2

CHRANZ(2011)providesdeeperinsighttothisissue.

Figure4:Wageandpricelevelsinconstructionrelativetotheaggregateeconomy

170 160 150 140 130 120 110 100 90 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Source:StatisticsNewZealandQuarterlyEmploymentSurveyandCPI

CPI - Construction CPI - All sectors Wages - Construction Wages - All sectors

Taxissues Housing is a favoured investment from a tax treatment perspective.This is especially so for unleveraged owneroccupiers(seeHargreaves2008),sinceowneroccupiersdonotpaytaxonthe imputedrentalvalueoftheequityintheirhouses(althoughtheydopayrates).Theinadequatetax treatment of the inflation component of interest, whereby all interest received is taxed and all interestpaymentsbyinvestorsaredeductible,compoundsthedistortionandextendsittotherental propertysector.Withaninflationtargetcentredon2percentperannum,asignificantchunkofthe any interest rate reflects simply the expected general rise in the price level (rather than a real incomeorrealcost). Thetaxtreatmentofhousingandsavingsproductsvarieswidelyacrosscountries.Taxregimescan beshowntoinfluenceboththelevelandvolatilityofhouseprices(seeHargreaves2008andvanden Noord 2003, for example), especially when supply responses are sluggish. But countries with a varietyoftaxregimesexperiencedsimilarhousingboomsinthemidtolate2000s.Moreover,itis notclearthat,inaggregate,housingismoretaxfavouredinNewZealandthaninothercountries. Forexample,householdersintheUScandeductowneroccupierinterestpaymentsfortaxpurposes andinmostcasesfacenocapitalgainstax.Inaddition,relativelyhighlocalgovernmentratesinNew Zealandcomparedtoothercountries,actasataxonpropertyownership. Some have also argued that the increase inthe maximum marginal tax rate in 2000 (perhaps in combinationwiththechangeintheinflationtargetin2002)playedamajorroleinthelastcycle.We are sceptical for a variety of reasons outlined in our 2007 work.At most, we believe it was an exacerbatingandamplifyingfactor.Atthetime,theunderlyingregulatorymodelmadenewhousing supply relatively slow to respond and expectations of persistent future price increases became entrenched for a time.We also doubt that lossoffsetting in and of itself, was more than an amplifying factor, because rental yields at the start of the housing boom were high enough (and interestratesrelativelylow)thatlargelosseswerelimited.Moregenerally,however,correctingthe

taxtreatmentofinteresttoassessordeductonlyrealinterestwouldremovethedistortioninthis area. One tax issue that periodically receives considerable attention is capital gains taxation. Houses boughtbyinvestorswiththeintentiontoresellarealready,inprinciple,caughtbytheincometax net,butNewZealanddoesnothaveageneralcapitalgainstax.TheReserveBankhasnevertakena stanceonthegeneralmeritsorotherwiseofcapitalgainstaxes.Wehavefairlyconsistentlynoted (including in the Supplementary Stabilisation Instruments report (Blackmore et al 2006) and the 2007 submission to the Commerce Committee) that there is little evidence internationally that countrieswithcapitalgainstaxeshaveexperiencedlessmarkedcyclesinhouseprices.Inthe2007 document, we noted that, in practice, capital gains taxes are only levied on realised gains (rather than accruals), which creates additional distortions and that capital gains taxes usually largely exclude owneroccupied houses, even though unleveraged owneroccupied housing is the most lightlytaxedcomponentofthehousingstock.Wesummedupthatcapitalgainstaxesarecommon internationallybutarehardtodesignandimplementinawaythatworkswell.Toavoidestablishing newdistortions,anycapitalgainstaxshouldonlytaxrealcapitalgainsandneedstotreatgainsand lossesrelativelysymmetrically. Financialliberalisation The liberalisation of access to finance since the 1980s has allowed a rise in aggregate debt levels, andaffectedthedistributionofdebt.Asinmanyothersimilardevelopedcountries,itislikelythat financial deregulation affected the savings and housing finance decisions of New Zealanders (see Coleman2007andHull2003).Togetherwithlowerinflationandlowernominalinterestratessince theearly1990s,deregulationallowedhouseholderstoservicemoredebtwithafixedproportionof theirincome.Withhousingsupplyslowtoadjust,easieraccesstofinance,especiallyinthepresence of other demand shocks, resulted in large increases in house prices. Higher prices fuelled expectationsoffurtherappreciation,whichservedtoreinforcehigherhousingdemand. Over the longterm, changes in access to finance should not have a large or sustained effect on houseprices.InmuchoftheUnitedStates,forexample,withhistoricallyrelativelyliberalaccessto housingfinanceandsimilardebttoincomeratiosasinNewZealandandAustralia,realhouseprices (andhousepricetoincomeratios)aremateriallylowerthanthoseinNewZealand(seeNewZealand ProductivityCommission2011,p.13andp.15).Themoreimportantfactorsareprobablytheability touseadditional land forhousing (ortouseexisting landmoreintensively),andthevalue ofthat landinalternativeuses. Policyfocus What does this mean for the appropriate focus for policy? Policy should focus on the firstbest solutionprovidingaregulatoryenvironmentthatgetstheunderlyingsupplyconditionsright.New Zealandneedstoensurethatlandusecanchangerelativelyreadilytowardsthemostvaluableuse forthatland,especiallyifitspopulationistocontinuetogrowrelativelyrapidly.NewZealandalso needsaregulatoryenvironmentthatenablesahighlyproductiveresidentialconstructionsector.In combination,suchchangestothesupplyconditionswouldhelplimittheriskoflargefutureswings in house prices when demand shifts occur. House price swings of the sort that we have seen recentlyaredamagingtoNewZealandsoveralleconomicperformance.Attimes,housepricecycles canalsounnecessarilycomplicatemacroeconomicpolicyandposeavoidablerisksforindividualand systemwidefinancialstability.

10

Avoiding tax preferences for housing and removing the distortionary tax treatment of interest are also measures that would tend to enhance the policy environment in which housing markets can function.Inasecondbestworldwheresupplyisnotparticularlyresponsive,policymightalsolook whetherthereisscopetomanagemigrationinflowsofnonNewZealandersinawaythatlimitsthe contribution to cyclical demand pressures. However, implementation lags are likely to pose challenges. Possible stabilisation advantages would need to be weighed carefully against potential disruption to the mediumterm migration programme and policy would need to take a whole of government approach. More generally, better coordination of government policies that affect housingsupplyanddemandwouldbehelpful. Looking ahead, the Reserve Bank can respond, if and when future house price bubbles build up, usingseveralmacroprudentialinstruments.Thesecouldincludeincreasingcapitalrequirementsfor banks,usingmacroprudentialcapitaloverlaysorapplyingmorerestrictiveloantovaluelimitsduring booms.But these are tools for when booms are already well underway and systemic risks are beginningtomount.Abetterunderlyingpolicyenvironmentwouldreducetheriskofundulylarge housingpricecyclesinthefirstinstance.Amoreresponsivenesshousingmarketwillnotonlybetter meetthechangingdemandsofNewZealandhouseholds, butwillalsoreducetheextenttowhich thebehaviourofthehousingmarketisacauseforconcernamongmacropolicymakers.

Ref#4486349

11

References Blackmore,M,PBushnell,TNg,AOrr,MReddellandGSpencer(2006)"Supplementarystabilisation instruments: Initial report to Governor, Reserve Bank of New Zealand and Secretary to the Treasury". Bollard,A.(2004),AssetPricesandMonetaryPolicy.AddresstotheCanterburyEmployersChamber ofCommerce,Christchurch. CalderaSanchez,A.andA.Johansson(2011),ThepriceresponsivenessofhousingsupplyinOECD countries,OECDEconomicsDepartmentWorkingPapers,no.837,OECD:Paris. Cheung,C.(2011),PoliciestoRebalanceHousing.MarketsinNewZealand,OECD. CHRANZ (2010) Auckland Regional Housing Market Assessment Vol 1: Main Report, Report preparedbyDarrochLtd. CHRANZ(2011),Whyhaveresidentialconstructioncostsincreasedmorethancostsinothersectors oftheNewZealandeconomy? Coleman,A(2007),CreditconstraintsandhousingmarketsinNewZealand,ReserveBankofNew ZealandResearchDiscussionPaper2007/11 Coleman,AandJLandonLane(2007),HousingmarketsandmigrationinNewZealand:19622006, ReserveBankofNewZealandResearchDiscussionPaper2007/12 Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2008) Final report of the house prices unit: house priceincreasesandhousinginNewZealand,Wellington. DeVeirman,EandDunstan,A(2008),Howdohousingwealth,financialwealthandconsumption interact? Evidence from New Zealand, Reserve Bank of New Zealand Research Discussion Paper 2008/05. De Veirman, E. and Ashley Dunstan (2011): `TimeVarying Returns, Intertemporal Substitution and CyclicalVariationinConsumption,theB.E.JournalofMacroeconomics(Topics),forthcoming. Glaeser, E, J Gyourko and A Saiz (2007), Housing supply and housing bubbles, Journal of Urban Economics,64(2),pp198217 Glaeser, E and B A Ward (2009), The causes and consequences of land use regulation: evidence fromgreaterBoston,JournalofUrbanEconomics,65(3),pp26578 Goldman Sachs (2010). A Study On Australian Housing: Uniquely Positioned Or A Bubble?. 6 September2010 Grimes,AandAAitken(2006).HousingSupplyandPriceadjustment,WorkingPaper0601,Motu EconomicandPublicPolicyResearch Grimes, A and Y Liang (2007), Spatial Determinants of land prices in Auckland: Does the MetropolitanUrbanLimithaveaneffect?,WorkingPapers0709,MotuEconomicandPublicPolicy Research

Ref#4486349

12

Hargreaves,D(2008),ThetaxsystemandhousingdemandinNewZealand,ReserveBankofNew ZealandResearchDiscussionPaper2008/06. Huang, H and Y Tang (2010), Residential Land Use Regulation and the US Housing Price Cycle, UniversityofAlbertaWorkingPaperSeries Hull,L(2003),Financial deregulationandhousholdindebtedness,ReserveBankofNewZealand ResearchDiscussionPaper2003/01 NewZealandProductivityCommission(2011).HousingaffordabilityIssuesPaper.June2011. OECD,(2011).EconomicSurveyofNewZealand2011. IMF(2008)Box3:HowovervaluedareNewZealandhouseprices?,NewZealand:Staffreportfor the2008ArticleIVconsultation,IMFCountryReportNo08/163,p17. Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2007), Submission from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to the CommerceCommitteeontheinquiryintohousingaffordability. Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2007), Reserve Bank of New Zealand Board Submission to: FEC InquiryintotheFutureMonetaryPolicyFramework. Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2010), Reserve Bank of New Zealand Board Submission to: the SavingsWorkingGroup. Sanchez, Aida Caldera and Asa Johansson (2011), The price responsiveness of housing supply in OECDcountries,OECDEconomicWorkingPaperNo.837. Smith,M(2010),Evaluatinghouseholdexpendituresandtheirrelationshipwithhousepricesat themicroeconomiclevel,ReserveBankofNewZealandResearchDiscussionPaper2010/01. Stephens,D(2007),Bubble,schmubble,WestpacEconomicResearch. Van den Noord, Paul (2003) Tax incentives and house price volatility in the euro area, OECD Working PaperNo.356. White, W (2009) Should Monetary Policy Lean or clean?, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, GlobalizationandMonetaryPolicyInstituteWorkingPaperNo.34.

Ref#4486349

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- MCQs on Defence Audit Code Chapter 9 and 10Document2 pagesMCQs on Defence Audit Code Chapter 9 and 10Rustam SalamNo ratings yet

- CEMEX Global Strategy CaseDocument4 pagesCEMEX Global Strategy CaseSaif Ul Islam100% (1)

- Auditing For Managers - The Ultimate Risk Management ToolDocument369 pagesAuditing For Managers - The Ultimate Risk Management ToolJason SpringerNo ratings yet

- 91 SOC Interview Question BankDocument3 pages91 SOC Interview Question Bankeswar kumarNo ratings yet

- 02 - AbapDocument139 pages02 - Abapdina cordovaNo ratings yet

- Willie Chee Keong Tan - Research Methods (2018, World Scientific Publishing Company) - Libgen - Li PDFDocument236 pagesWillie Chee Keong Tan - Research Methods (2018, World Scientific Publishing Company) - Libgen - Li PDFakshar pandavNo ratings yet

- Cryptography Seminar - Types, Algorithms & AttacksDocument18 pagesCryptography Seminar - Types, Algorithms & AttacksHari HaranNo ratings yet

- BIM and AM to digitally transform critical water utility assetsDocument20 pagesBIM and AM to digitally transform critical water utility assetsJUAN EYAEL MEDRANO CARRILONo ratings yet

- HSBC China Flash PMI (23 Sept 2013)Document3 pagesHSBC China Flash PMI (23 Sept 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RP Data Property Pulse (11 October 2013)Document1 pageRP Data Property Pulse (11 October 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Phat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (19 Sept 2013)Document3 pagesPhat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (19 Sept 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- ANZ Property Industry Confidence Survey December 2013Document7 pagesANZ Property Industry Confidence Survey December 2013leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Wilson HTM - ShortAndStocky (20130916)Document22 pagesWilson HTM - ShortAndStocky (20130916)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Aig Pci August 2013Document2 pagesAig Pci August 2013leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RP Data Weekend Market Summary WE 13 Sept 2013Document2 pagesRP Data Weekend Market Summary WE 13 Sept 2013Australian Property ForumNo ratings yet

- Westpac Red Book (September 2013)Document28 pagesWestpac Red Book (September 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Saul Eslake - Henry George Dinner Sep 2013 (Slides)Document13 pagesSaul Eslake - Henry George Dinner Sep 2013 (Slides)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Wilson HTM Valuation Dashboard (17 Sept 2013)Document20 pagesWilson HTM Valuation Dashboard (17 Sept 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Phat Dragon Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (6 September 2013)Document3 pagesPhat Dragon Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (6 September 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- HIA Dwelling Approvals (10 September 2013)Document5 pagesHIA Dwelling Approvals (10 September 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Media Release - The Vote Housing Special-1Document3 pagesMedia Release - The Vote Housing Special-1leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Westpac - Where Have The FHBs Gone (August 2013)Document6 pagesWestpac - Where Have The FHBs Gone (August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Phat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (28 August 2013)Document3 pagesPhat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (28 August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Weekend Market Summary Week Ending 2013 August 25 PDFDocument2 pagesWeekend Market Summary Week Ending 2013 August 25 PDFLauren FrazierNo ratings yet

- Shale - The New World (ANZ Research - August 2013)Document18 pagesShale - The New World (ANZ Research - August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- NZ PC On Aucklands MUL (March 2013)Document23 pagesNZ PC On Aucklands MUL (March 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RP Data - Rising Sales To Benefit Agents (August 2013)Document1 pageRP Data - Rising Sales To Benefit Agents (August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Phat Dragon (23 August 2013)Document3 pagesPhat Dragon (23 August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- HIA - Housing Activity During Business Cycles (August 2013)Document8 pagesHIA - Housing Activity During Business Cycles (August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RP Data - Steady Decline in Home Ownership (8 August 2013)Document1 pageRP Data - Steady Decline in Home Ownership (8 August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- ME Bank Household Financial Comfort Report (July 2013)Document32 pagesME Bank Household Financial Comfort Report (July 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Westpac - Fed Doves Might Have Last Word (August 2013)Document4 pagesWestpac - Fed Doves Might Have Last Word (August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- ANZ - Retail Sales Vs Online Sales (August 2013)Document4 pagesANZ - Retail Sales Vs Online Sales (August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RBA Statement of Monetary Policy (August 2013)Document62 pagesRBA Statement of Monetary Policy (August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RP Data - Brisbane & Adelaide Housing (15 August 2013)Document1 pageRP Data - Brisbane & Adelaide Housing (15 August 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Genworth Streets Ahead Report (July 2013)Document8 pagesGenworth Streets Ahead Report (July 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- Age Bias in The Australian Welfare State (ANU 2013)Document16 pagesAge Bias in The Australian Welfare State (ANU 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- RP Data Home Values Results (July 2013)Document4 pagesRP Data Home Values Results (July 2013)leithvanonselenNo ratings yet

- CCW Armored Composite OMNICABLEDocument2 pagesCCW Armored Composite OMNICABLELuis DGNo ratings yet

- Ibad Rehman CV NewDocument4 pagesIbad Rehman CV NewAnonymous ECcVsLNo ratings yet

- 22 Caltex Philippines, Inc. vs. Commission On Audit, 208 SCRA 726, May 08, 1992Document36 pages22 Caltex Philippines, Inc. vs. Commission On Audit, 208 SCRA 726, May 08, 1992milkteaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Ethics in Practice ShorterDocument79 pagesEngineering Ethics in Practice ShorterPrashanta NaikNo ratings yet

- ITC Report and Accounts 2016Document276 pagesITC Report and Accounts 2016Rohan SatijaNo ratings yet

- Investigations in Environmental Science: A Case-Based Approach To The Study of Environmental Systems (Cases)Document16 pagesInvestigations in Environmental Science: A Case-Based Approach To The Study of Environmental Systems (Cases)geodeNo ratings yet

- Naoh Storage Tank Design Description:: Calculations For Tank VolumeDocument6 pagesNaoh Storage Tank Design Description:: Calculations For Tank VolumeMaria Eloisa Angelie ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Critical Aspects in Simulating Cold Working Processes For Screws and BoltsDocument4 pagesCritical Aspects in Simulating Cold Working Processes For Screws and BoltsstefanomazzalaiNo ratings yet

- Sahrudaya Health Care Private Limited: Pay Slip For The Month of May-2022Document1 pageSahrudaya Health Care Private Limited: Pay Slip For The Month of May-2022Rohit raagNo ratings yet

- 341 BDocument4 pages341 BHomero Ruiz Hernandez0% (3)

- Hydropneumatic Accumulators Pulsation Dampeners: Certified Company ISO 9001 - 14001Document70 pagesHydropneumatic Accumulators Pulsation Dampeners: Certified Company ISO 9001 - 14001Matteo RivaNo ratings yet

- Computer Application in Business NOTES PDFDocument78 pagesComputer Application in Business NOTES PDFGhulam Sarwar SoomroNo ratings yet

- Flex VPNDocument3 pagesFlex VPNAnonymous nFOywQZNo ratings yet

- Counsel For Plaintiff, Mark Shin: United States District Court Northern District of CaliforniaDocument21 pagesCounsel For Plaintiff, Mark Shin: United States District Court Northern District of CaliforniafleckaleckaNo ratings yet

- University of Cebu-Main Campus Entrepreneurship 100 Chapter 11 QuizDocument3 pagesUniversity of Cebu-Main Campus Entrepreneurship 100 Chapter 11 QuizAnmer Layaog BatiancilaNo ratings yet

- How To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingDocument10 pagesHow To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingMinh Dang HoangNo ratings yet

- Feedback Mechanism InstrumentDocument2 pagesFeedback Mechanism InstrumentKing RickNo ratings yet

- Moi University: School of Business and EconomicsDocument5 pagesMoi University: School of Business and EconomicsMARION KERUBONo ratings yet

- Banaue Rice Terraces - The Eighth WonderDocument2 pagesBanaue Rice Terraces - The Eighth Wonderokloy sanchezNo ratings yet

- Request For Information (Rfi) : Luxury Villa at Isola Dana-09 Island - Pearl QatarDocument1 pageRequest For Information (Rfi) : Luxury Villa at Isola Dana-09 Island - Pearl QatarRahmat KhanNo ratings yet

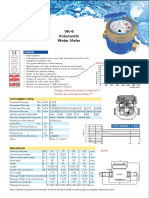

- Baylan: VK-6 Volumetric Water MeterDocument1 pageBaylan: VK-6 Volumetric Water MeterSanjeewa ChathurangaNo ratings yet

- Demecio Flores-Martinez Petition For Review of Enforcement of Removal OrderDocument9 pagesDemecio Flores-Martinez Petition For Review of Enforcement of Removal OrderBreitbart NewsNo ratings yet