Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Minority Squeeze Final

Uploaded by

gchen5Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Minority Squeeze Final

Uploaded by

gchen5Copyright:

Available Formats

EQUITY DERIVATIVES GLOBAL

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Evren Ergin, Ph.D. 1.201.524.4212 eergin@lehman.com Christian Correa 1.201.524. 4212 ccorrea@lehman.com

U.S. Risk Arbitrage Research Andrew T. Whittaker Evren Ergin, Ph.D. Sugun V. Kapoor Christian Correa 1.201.524.4212

We review different minority squeeze-out transaction structures and the legal standards applicable in Delaware law to these situations. We then present nine case studies of minority squeeze-outs, review their general characteristics, and discuss some descriptive statistics based on these cases. Finally, we describe a methodology for calculating the probability of a bump in deal terms for minority squeeze-outs. We apply this methodology to a number of past deals to discuss its implications. n The acquirer may conduct a tender offer rather than take its offer directly to the target board so as to exert some timing and pricing discipline on the evaluation process. n It appears that acquirers were able to afford larger premiums in recent transactions partly because of the large decline in target prices over the three-month period preceding deal announcements. n As long as the expected upside from a bump in the terms more than compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital, lower (or more negative) arbitrage spreads imply higher probabilities of a bump, with all else being equal. n In a typical minority squeeze -out situation in which the initial spread is negative (or positive, but narrow) and risk arbitrageurs stand to incur losses upon deal termination, a lower expected bump implies a higher probability of a bump, all else being equal. n As long as the expected upside from a bump in the terms more than compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital, the greater the expected loss upon deal termination, the more positive (or less negative) the spread needs to be for investors to be willing to put on a risk arbitrage position, with all else being equal.

January 3, 2002

http://www.lehman.com

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................... 3 Transaction Structures and Legal Issues ............................................................... 5 Transaction Structures and Deal Outcomes........................................................ 5 Legal Standards in Delaware Law for Minority Squeeze-Outs................................ 5 Characteristics of Nine Minority Squeeze-Outs and Their Descriptive Statistics............. 8 Deal Background and Summaries ................................................................... 8 Qualitative Characteristics........................................................................... 13 Descriptive Statistics................................................................................... 15 Future Minority Squeeze-Outs?..................................................................... 19 What is the Probability of a Bump? Probability Analysis in Minority Squeeze-Outs...... 20 Synopsis of Framework and Main Assumptions................................................ 20 Results..................................................................................................... 21 Conclusion................................................................................................. 30 Appendix................................................................................................... 33 Probability Framework................................................................................ 33 Trading Considerations............................................................................... 35

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Introduction In a minority squeeze -out, a shareholder (acquirer) who owns a majority or a substantial portion of a targets outstanding shares offers to purchase the target shares it does not already own. The acquirer may be the parent of previously carved-out subsidiary or an affiliate that has previously bought a substantial stake in the target. In either case, the acquirers objective is to consolidate its ownership in the target by purchasing the publicly held minority shares. The acquirers offer may be structured as a tender offer, a merger, or a tender offer followed by a second-step merger. The interaction between the acquirer and the target b oard in transactions involving mergers may be subject to conflicts of interest. By virtue of holding a significant stake in the target, the acquirer typically has representation on the targets board of directors. Several of the target directors are usually officers of the acquiring company. These directors have fiduciary duties to both the target and the acquirer and may thus face conflicts of interest in minority squeeze-out transactions. In order to avoid lawsuits alleging breach of fiduciary duty or unfair dealing, the target board typically establishes a special committee of independent directors shortly after the receipt of an acquisition proposal. The special committee evaluates the offer, negotiates with the acquirer, and makes a recommendation to the board of directors. The board has the final decisionmaking authority and typically follows the recommendation of the special committee. Even if a transaction is structured as a tender offer, the acquirer may deal with a special committee of the targets board of directors to fend off allegations of unfair price or unfair dealing, to reduce the risk of failure, and to give itself flexibility. In most minority squeeze-outs, negotiations between the acquirer and the special committee result in a higher offer and a recommendation of the transaction by the target board to the companys shareholders. The initial offer is typically perceived to be a lowball figure, as part of the negotiating strategy of the acquirer. This perception is reflected in the targets share price, as it tends to trade very close to or above the offer price. The final offer received by the target shareholders depends on a number of factors including the value of the target company as a going-concern, motivation of the acquirer, concentration of control among minority shareholders, existence of other potential buyers, negotiating power of the acquirer, and premiums offered in comparable transactions. An offer higher than the initial one is not a guaranteed outcome. Negotiations with the target board may not lead to any agreement, and the acquirer might terminate the offer. In a tender offer, the acquirer may not be able to obtain sufficient shares to complete the transaction. It is also possible that the deal is completed without a bump in the terms, following an endorsement by the target board or acceptance by target shareholders. This report contains three main sections. In the first section, we review different minority squeeze -out transaction structures and the legal standards applicable in Delaware law in these situations. In the second section, we present nine case studies of minority squeeze January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

outs, review their general characteristics, and discuss some descriptive statistics based on these cases. At the end of the second section, we also list a number of potential minority squeeze -out situations based on the implications of our analysis. In the last section, we describe a methodology for calculating the probability of a bump in deal terms for minority squeeze-outs. We apply this methodology to a number of past deals to discuss its implications. In the appendix, we present the derivation of our methodology and also discuss trading considerations.

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Transaction Structures and Legal Issues Transaction Structures and Deal Outcomes The timing and value of the final offer in a minority squeeze -out may depend on the transaction structure. The minority squeeze-out may be in the form of proposed merger or a tender offer made to target shareholders. A structure that involves a me rger may require the approval of the target board of directors. A tender offer by itself does not require target board approval, and the acquirer may take the offer directly to target shareholders.1 In situations involving proposed mergers, the actions of target directors are subject to the entire fairness standard in Delaware courts. In contrast, this standard is not applicable to tender offers made directly to target shareholders by controlling shareholders. The target directors do not have a duty to demonstrate entire fairness in these tender situations.2 The inapplicability of the entire fairness standard is likely to limit the extent of shareholder litigation. Taking the offer directly to shareholders may also facilitate negotiations with the special committee, since the acquirers decision to initially bypass the board could give the board an incentive to become involved in the process. Moreover, in direct tender offers, the special committee may have less bargaining leverage than it would in a proposed merger because the targets decision-making authority is delegated to the target shareholders rather than to the directors. The acquirer is not obliged to interact with a special committee in direct tender offers. Completely circumventing the target board, however, is likely to incite greater shareholder opposition. In addition, the acquirer would have to rely on obtaining sufficient target shares (90%) to be able to conduct a short-form merger.3 Reaching a compromise with the targets special committee may serve the acquirers interests by reducing the probability of failure in the tender offer. Legal Standards in Delaware Law for Minority Squeeze-Outs Squeeze -outs have built-in conflicts of duties and high risk of litigation. The board of the target is usually made up of a majority of appointees from the controlling corporation. These directors have conflicting duties: a duty to the shareholders of the target to maximize the price paid and a duty to the shareholders of the controlling corporation to minimize the price paid. In light of this conflict, the decisions of directors are not

Note that the acquirer typically has a control position, and therefore poison pills and change of control statutes are generally not applicable.

2

In Re Siliconix Incorporated Shareholders Litigation, Delaware Chancery Court, Consolidated C.A. No. 18700, John W. Noble, V.C., Memorandum Opinion (June 19, 2001).

3

The short-form merger does not require target board or shareholder votes. January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

reviewed by Delaware courts under the business judgment rule.4 Instead, a Delaware court will apply the entire fairness test. Entire Fairness. The entire fairness test requires that the proponents of the transaction not the plaintiffsbe able to show that the transaction was arrived at through fair dealing and is at a fair price. This standard is broad in scope and very demanding. Fair dealing is a broad standard which looks at the deal timing, the process by which it was initiated, negotiated, and structured, and how the approval of directors and shareholders was obtained. Full disclosure of material information, particularly to outside directors, is crucial. This includes information which would ordinarily never be disclosed, like internal financial analysis of the deal valuation. Fair price standards have been set by appraisal cases, even though appraisal rights are not technically invoked. The appraisal laws look at all relevant factors, including asset values, market values, comparable transactions, historical earnings, discounted cash flows, and future prospects. Expert advice and an opinion from an investment banker that the value is fair ar e often used to establish a fair price. Fair value may exclude speculative elements and merger synergies or cost savings. Fair value does not include a minority discount reflecting the lack of control. A fair price does not necessarily imply fair dealing and vice versa. Broadly speaking, both elements of the test must be satisfied and court precedents exist where a fair price was found yet plaintiffs won the case on fair dealing grounds as well as the converse. However, in a squeeze-out the dominant concern is fair price, followed by disclosure of material information. weighed as heavily. Role of the Special Committee. The most common technique for satisfying the courts entire fairness standard is the appointment of a special committee. A committee of outside directors who are disinterested may be appointed by the targets board of directors to approve the transaction. This committee negotiates on behalf of the entire board, representing the interests of minority shareholders and protecting the controlling company from legal liability. A special committee must be disinterested and capable of performing its task. This Broader indications of fair dealing beyond disclosure are not

involves being informed, having appropriate incentives and having access to good, independent legal and financial advice. With this support a special committee should seek the best possible price without rejecting a transaction that is in the interest of minority shareholders. A concomitant of this is that the controlling corporation is limited

The business judgment rule shields directors from being second-guessed by courts. A court applying the rule will defer to the business judgment of the directors. A director can still be liable for gross negligence under the business judgment rule.

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

in its ability to withhold information from the special committee or use certain tactics, including take-it-or-leave-it offers. Note that the special committee does not necessarily have the power to shop the company to other buyers, and the controlling company is not obliged to follow through on its offer. A controlling company can withdraw in light of unfavorable negotiations before a definitive agreement is signed. A squeeze-out may proceed over the opposition of the special committee. Techniques which may be used to avoid violating entire fairness include granting appraisal rights to all minority shareholders, allowing the minority shareholders to receive shares in the controlling corporation as consideration, thus participating in merger synergies, or conditioning the transaction on a vote of the minority shareholders.

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Characteristics of Nine Minority Squeeze-Outs and Their Descriptive Statistics In this section, we highlight nine minority squeeze -out transactions. These deal s as well as their initial and final terms are listed in Figure 1. Six of these transactions (late 2000/early 2001) are fairly high-profile deals that took place in a bull market and attracted considerable arbitrage interest. The remaining three transactions took place recently in a bear market and were resolved quickly. Figure 29 at the end of the report includes additional information about the timing, premiums, values and market conditions with respe ct to each squeeze-out. Below, we first provide a brief background and synopsis for each of the transactions. Following the summaries, we discuss their general characteristics and any statistical patterns that emerge from the case studies. Figure 1: Initial and Final Deal Considerations in Highlighted Transactions

Deal AXA Financial / AXA Hertz / Ford Infinity Broadcasting / Viacom Delhaize America / Delhaize Le Lion Avis Group / Cendant Sodexho Marriott Services / Sodexho Alliance TyCom / Tyco Prodigy Communications / SBC TD Waterhouse / Toronto-Dominion Bank Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg Ann. Date 30-Aug-00 21-Sep-00 15-Aug-00 7-Sep-00 15-Aug-00 25-Jan-01 4-Oct-01 24-Sep-01 10-Oct-01 Bump Date Closing Date Initial Cash 18-Oct-00 17-Jan-01 31-Oct-00 17-Nov-00 13-Nov-00 2-May-01 19-Oct-01 18-Oct-01 30-Oct-01 5-Jan-01 9-Mar-01 23-Feb-01 26-Apr-01 1-Mar-01 21-Jun-01 18-Dec-01 7-Nov-01 27-Nov-01 $32.10 $30.00 --$29.00 $27.00 -$5.45 $9.00 Final Cash $35.75 $35.50 --$33.00 $32.00 -$6.60 $9.50 Initial Stock 0.271 -0.564 0.35 --0.2997 --Final Stock 0.295 -0.592 0.4 --0.3133 ---

Deal Background and Summaries AXA Financial/AXA AXA Group (AXA $20.15; Not rated)5 made an investment in Equitable Companies (subsequently AXA Financial) in July 1991. On July 22, 1992, Equitable Companies completed an initial public offering of common shares. After the IPO, AXA owned 48% of Equitable common stock. As of the time of the minority squeeze-out, AXA owned 60.3% of AXA Financial shares outstanding. On August 30, 2000, AXA Group proposed to acquire the 39.7% of AXA Financial shares outstanding that it did not already own. The proposal was subject to the approval of AXA Financial board of directors. The initial offer consisted of 0.271 AXA shares and $32.10 cash. AXA Financial formed a special committee of independent directors to review the offer. On October 18, 2000, the special committee approved the sweetened offer of 0.295 AXA shares and $35.75 cash, and the companies also signed a definitive merger agreement. AXA adopted an exchange offer/second-step

All prices are as of the December 21, 2001 market close.

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

merger structure, with the possibility of conducting a short-form merger.6 The transaction closed on January 5, 2001. Hertz/Ford Ford Motor Company (F $15.45; 2 Buy) first acquired an ownership interest in Hertz in 1987. Hertz became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Ford as a result of a series of transactions in 1993 and 1994. On April 30, 1997, Hertz issued and sold shares of its Class A common stock in an initial public offering. After the IPO, Ford beneficially owned 49.4% of the outstanding Hertz Class A common stock (with one vote per share) and 100% of the outstanding Hertz Class B common stock (with five votes per share). As of December 31, 1999, Ford had 94.6% voting power and 81.2% economic interest in Hertz. On September 21, 2000, Ford Motor Company proposed to acquire the 18.5% of Hertz outstanding stock that it did not already own through a merger transaction. The initial offer was $30 cash. The proposed merger was subject to Hertz board approval and the negotiation, execution, and performance of a definitive merger agreement. On January 17, 2001, Ford reached an agreement with the Hertz special committee and board of directors and increased its offer to $35.50 cash. The merger was completed on March 9, 2001. Infinity/Viacom Infinity Broadcasting Corp. was incorporated in September 1998 to own and operate the radio and outdoor advertising business of CBS Corp. (later acquired by Viacom). In December 1998, Infinity completed an initial public offering of its Class A common stock. On May 4, 2000, CBS merged with Viacom (VIA/B $41.70; 1 Strong Buy), and consequently, Infinity became a majority-owned subsidiary of Viacom. represented approximately 64.2% of the equity and 90.0% of the voting power. On August 15, 2000, Viacom offered to purchase the remaining shares of Infinity that it did not already own in a merger transaction. The initial offer was 0.564 VIA/B shares. The merger proposal was subject to the approval of the independent directors of Infinity. A number of lawsuits were filed by shareholders seeking a higher consideration following the initial announcement. On October 31, 2000, the companies reached a definitive merger agreement after Viacom raised its offer to 0.592 VIA/B shares. adopted a merger structure for the exchange of shares. Viacom On January 5, 2001, the As of September 30, 2000, Viacom held 100% of the Infinitys Class B common stock, which Ford adopted a cash offer/second-step merger structure, with the possibility of conducting a short-form merger.

Delaware law allows an acquirer that holds more than 90% of target shares outstanding to conduct a short-form merger without the requirement of holding a target shareholder meeting. January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

companies announced that Infinity would hold a shareholder meeting to seek approval on the merger.7 The transaction closed on February 23, 2001. Delhaize America/Delhaize Le Lion Delhaize America, Inc. was incorporated in North Carolina in 1957. As of 2000, it was the largest operating company in the global supermarkets group of Delhaize Le Lion (Brussels: DELB e58.70; 2 Buy). Before the minority squeeze-out transaction, the Delhaize Group owned approximately 37% of Delhaize America's Class A (non-voting) common stock and approximately 56% of its Class B (voting) common stock, or approximately 45% of Delhaize America's total shares outstanding. On September 9, 2000, Delhaize Le Lion proposed to acquire, contingent on the approval of Delhaize Americas board and independent directors, 55% of Delhaize Americas total shares outstanding that it did not already own. The initial offer was 0.35 DELB shares for every share of Delhaize America. The companies reached an agreement for a statutory share exchange under North Carolina Corporation Law on November 17, 2000 at a final offer of 0.40 DELB shares. The share exchange was completed on April 26, 2001. Avis Group/Cendant On October 17, 1996, Cendant (CD $19.60; 1 Strong Buy) purchased Avis, Inc. and its subsidiaries (subsequently Avis Group Holdings). On September 24, 1997, Avis completed an initial public offering of its common stock. Before the minority squeeze-out transaction, Cendant owned approximately 18% of Avis' outstanding common shares and also owned preferred stock of an Avis subsidiary that was convertible into Avis shares. These preferred shares were convertible into a combination of non-voting and voting Avis Group common shares that would have resulted in Cendant having up to a 20% voting interest in Avis Group and approximately a 33% economic interest. On August 15, 2000, Cendant Corporation made a preliminary and non-binding proposal to acquire all of the outstanding shares of Avis Group that it did not already own for $29 per share in cash. Avis appointed a special committee of independent directors to evaluate the proposal. Some Avis shareholders filed class action complaints at the Delaware Chancery Court, claiming that the Cendant offer was inadequate. The companies reached a definitive merger agreement on November 13, 2000, after Cendant increased the offer to $33 per share. Cendant adopted a cash merger structure for the transaction. The merger was conditioned upon approval of a majority of the votes cast by Avis Group stockholders who were unaffiliated with Cendant. The merger closed on March 1, 2001.

The decision to hold a shareholder meeting came after a Delaware Chancery court decision regarding Digex created uncertainty about whether such a vote might be required for Delaware corporations.

10

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Sodexho Marriott Services/Sodexho Alliance On March 27, 1998, Sodexho Marriott Services (Marriott at the time) consummated a series of transactions that, among others, resulted in the acquisition of the North American operations of Sodexho Alliance, S.A. (Paris: SW -e46.76; 3 Market Perform). Concurrent to this transaction, all businesses of Marriott other than food services and the facilities management business were spun off to Marriotts shareholders through a special dividend of stock in a new companyMarriott International, Inc. Following the transactions, the former Marriott was renamed Sodexho Marriott Services, Inc. As part of the transactions, Sodexho Marriott Services and Sodexho entered into arrangements under which Sodexho provided Sodexho Marriott Services with a variety of consulting and advisory services and guaranteed a portion of its indebtedness. Sodexho Alliance has owned an approximate 48% stake in Sodexho Marriott Services ever since the formation of the company. On January 25, 2001, Sodexho Alliance proposed to acquire all the Sodexho Marriott Services shares that it did not already own for $27 in cash per share. This offer was conditional on due diligence and negotiation and execution of a definitive merger agreement. Following the announcement, a number of class action complaints were filed in the Delaware Chancery Court alleging that the Sodexho Alliance offer did not provide adequate value to Sodexho Marriott shareholders and that the defendants were breaching their fiduciary duties. On May 2, 2001, the companies reached a definitive merger agreement after Sodexho Alliance increased its offer to $32 and the Sodexho Marriott Services board of directors received the recommendation of its special committee. Sodexho Alliance adopted a cash offer/second-step merger structure, with the possibility of conducting a short-form merger. The transaction was completed on June 21, 2001. TyCom/Tyco TyCom was incorporated on March 8, 2000 as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Tyco (TYC $58.20; 1 Strong Buy) to serve as the holding company for its undersea fiber optic cable communications business. On July 27, 2000, TyCom sold approximately 14% of its common shares in an initial public offering. Before the minority squeeze-out, Tyco held 89% of TyCom common shares. On October 4, 2001, Tyco International offered to acquire the outstanding 11% minority interest in TyCom to bring TyCom back into the Tyco corporate structure as a whollyowned subsidiary. The initial offer was 0.2997 Tyco shares. The offer was conditional on the negotiation and execution of a definitive merger agreement. The transaction was challenged in an investor lawsuit alleging that Tyco was using its majority control of TyCom to reach an agreement that did not give TyCom's minority shareholders an adequate or fair price for their stock. The companies reached a definitive agreement on October 19, 2001, after Tyco increased its offer to 0.3133 TYC shares. transaction closed on December 18, 2001.

January 3, 2002

The

11

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Prodigy/SBC On February 11, 1999, Prodigy completed an initial public offering of its stock. In May 2000, Prodigy and SBC (SBC $39.30; 1 Strong Buy) established a strategic operating partnership in which SBC acquired an initial indirect interest in Prodigy of approximately 43%. Per the terms of the partnership, SBC had the right to exchange its units in the operating partnership for shares of Class A common stock. Direct ownership of Class A shares was concentrated among Carlos Slim Helu, Carso Global Telecom and Telmex, whose collective ownership of Prodigy Class A common stock represented approximately 34.3% of the voting power of all outstanding securities of Prodigy. On September 24, 2001, SBC announced a tender offer for the shares of Prodigy that it did not already own for $5.45 per share. SBC indicated that it would commence the offer as soon as practicable. A number of class action complaints were filed in the Delaware Chancery Court, alleging that the SBC offer did not provide sufficient value to Prodigy shareholders, Prodigy directors faced conflicts of interest, and that certain directors were acting to better SBC interests at the expense of Prodigy public shareholders. Prodigy formed a special committee of independent directors to review the offer and advised its shareholders not to take any action until the board had a chance to complete its review. In early October, SBC representatives and a special committee of Prodigy independent directors engaged in discussions regarding the offer. On October 15, 2001, the companies informed the public that the special committee informally suggested a tender offer price of $6.55, whereas SBC indicated the possibility of increasing the offer price to the $6.00 to $6.25 range. On October 18, 2001, the companies reached a definitive agreement on a revised tender offer according to which SBC would pay $6.60 per share. closed on November 7, 2001. TD Waterhouse Group/ Toronto-Dominion Bank Waterhouse Investor Services, Inc. (now TD Waterhouse) was acquired in 1996 by Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD $25.52; Not rated). On June 23, 1999, TD Bank conducted an initial public offering of TD Waterhouse stock. On October 10, 2001, Toronto-Dominion Bank announced a cash tender offer for all of the approximately 12% of the outstanding shares of TD Waterhouse that it (and its subsidiaries) did not already own for $9.00 per share. The offer was conditioned upon the acquisition of sufficient shares such that Toronto-Dominion Bank would own at least 90% of the outstanding TD Waterhouse Group common stock (so as to be able to do a short-form merger). TD indicated initially that the commencement and completion of the tender offer or the consummation of the merger did not require any approval by the TD Waterhouse board of directors. The transaction was structured as a cash tender/second-step merger, with the possibility of a short-form merger. The transaction

12

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

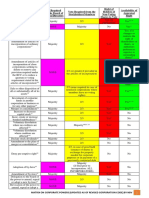

Following announcement, several investors filed class action complaints in the Delaware Chancery Court pointing to existing conflicts of interest and alleging that TorontoDominion was acting in its self interest at the expense o TD Waterhouse public f shareholders. On October 30, 2001, Toronto-Dominion Bank increased the offer to $9.50 per share in cash and revised the completion condition of the tender to require a majority of the publicly-held shares. The revision resulted from discussions between Toronto Dominion and the special committee of independent TD Waterhouse directors. The non-tendered shares were acquired through a short-form merger. The tender expired on November 14, 2001 and the transaction closed on November 27, 2001. Qualitative Characteristics Minority Squeeze-Out Process and Structure The target board appointed a special committee to evaluate the acquirers offer in all the transactions we highlight (Figure 2). Seven of the nine offers were conditional on target board approval and the signing of a definitive merger agreement. Following target board approval and the signing of a definitive agreement, the acquirers either initiated tender offers or mergers. Figure 2: Transaction Process and Structure

Deal % Target Shares Sought Conditional on Board Approval? Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Special Committee Appointed? Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Merger Agreement Reached? Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Structure of Transaction Exchange Offer Cash Offer Merger Share Exchange Merger Cash Offer Amalgamation Cash Offer Cash Offer Time to Bump

AXA Financial 39.7% Hertz 18.5% Infinity Broadcasting 35.7% Delhaize America 55.0% Avis Group 82.0% Sodexho Marriott Services 52.0% TyCom 11.0% Prodigy Communications 58.0% TD Waterhouse 12.0% Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg

49 118 77 71 90 97 15 24 20

In the remaining two situations, Prodigy/SBC and TD Waterhouse/Toronto-Dominion, the acquirer initiated a tender offer following announcement and did not seek the approval of the target board. Nevertheless, the target appointed a special committee. In these two deals, the acquirer and the target eventually reached an agreement on a final offer, and the target recommended the deal to its shareholders. The time from announcement to the final offer in these two transactions was considerably less than that in six of the other seven deals that were conditional on board approval. Even though the TyCom/Tyco deal required board approval, the bump came after only 15 days, most likely because the minority holdings represented a mere 11% of outstanding shares and the target board did not have much leverage. Shareholding Structure Investors who hold a disproportionately large number of target shares will have more incentive to oppose a transaction that they believe does not provide fair value.

January 3, 2002

13

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Concentration of shareholdings will make it more difficult for an acquirer to obtain the necessary vote in a merger or the necessary shares in a tender offer, if such investors are not appeased. In fact, large shareholders may also hold positions on the target board. Consequently, the acquirer may find it in its interest to negotiate with the target board and revise its offer in the presence of more concentrated shareholdings. It is interesting to note that the minority shareholdings in Prodigy and TD Waterhouse were not concentrated. These two deals are also the ones where the acquirers made their offers directly to target shareholders. Figure 3 lists the shareholdings of the top three and top 10 largest minority shareholders of five transactions that we highlight. The top 10 shareholders of Prodigy held 7.7% of total shares outstanding. For TD Waterhouse, this number is 4.5%. In the other transactions, which required board approval, the shareholdings were more concentrated than in the Prodigy and TD Waterhouse transactions. It is possible that acquirers have more incentive to negotiate with the board when the likelihood of opposition is higher due to concentrated shareholdings. We caution, however, that our sample size is too small to make any generalizations. Figure 3: Shareholding Structure

Transaction Infinity Broadcasting Avis Group Sodexho Marriott Services Prodigy Communications TD Waterhouse Holdings by 10 Largest Shareholders 26.6% 14.3% 12.1% 7.7% 4.5% Holdings by Three Largest Shareholders 25.0% 12.0% 9.3% 3.8% 3.3%

Notes: The list of shareholders does not include the acquirer ownership of target stock. Shareholding data was not available for the other highlighted transactions. Source: Bloomberg.

Premiums and Initial Conditions Performance of the target stock prior to the initial offer, ownership of the acquirer in the target, and market conditions before a transaction may have implications for the level of the initial premium. The acquirer may be able to offer a large initial premium for a target stock that has suffered a significant decline in its price recently, especially to the extent that the acquirer believes the decline is not entirely warranted. High ownership of target stock by the acquirer may imply that opposition to the initial offer could be muted, especially if the minority shareholdings are not very concentrated. conditions may reduce expectations of a large premium. Figure 4 provides an overview of the transactions based on the criteria described in the Notes. It appears that all transactions in our sample were announced at times when the target was trading near medium- to long-term highs or lows. The highs or lows of the target stocks do not necessarily match the highs or lows of the market across the board. In the transactions announced recently, however, market lows are associated with target stock price lows as well.

14

January 3, 2002

Poor market

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

The initial premiums in transactions where the targets were trading near their lows can be classified as moderate to high. Conversely, the initial premiums for targets with preannouncement prices near their high appear to be low to moderate-low. There does not appear to be a close relationship between the size of the bump and the initial premium. A low premium may be followed by a small bump, and a high premium may be followed by a large bump. We also do not detect a relationship between the pre-deal ownership of the target stock by the acquirer and the initial premium (or the size of the bump). Figure 4: Qualitative Overview of Highlighted Transactions

Deal Pre-Deal Target Price is Near High (all-time) Low (2-year) High (2-year) Low (2-year) High (6-month) High (2-year) Low (2-year) Low (2-year) Low (2-year) Pre-Deal Ownership Moderate -high High Moderate -high Moderate Low Moderate High Moderate High Pre-Deal Market Conditions Level (SPX) High High High High High Mod.-high Low Low Low Volatility (VIX) Low Low Low Low Low Moderate High High High Initial Premium One-day Low Moderate Moderate -low Moderate -low Moderate -low Low High High High One-w eek Low Moderate Moderate -low Moderate Moderate -low Low High Moderate -high Moderate -high Small Large Small Moderate Moderate Large Small Large Small Bump

AXA Financial Hertz Infinity Broadcasting Delhaize America Avis Group Sodexho Marriott Services TyCom Prodigy Communications TD Waterhouse

Notes: For pre-deal ownership, high means ownership in excess of 70%, moderate -high 60-70%, moderate 40-60%, low less than 30%. For the S&P 500 level, high means higher than 1400, moderate-high means 1300 to 1400, and low means less than 1100. For the VIX index, low means up to 25, moderate means 25 to 35, high means 35 and higher. For the initial premium, low means 0-10%, moderate -low means 10-20%, moderate means 20-30%, moderate high means 30-40%, and high means 40%+. For the bump, small means an absolute percentage point increase of 10 or less, moderate means an increase of 10 to 20, large means an increase of 20 or more. Source: Lehman Brothers.

Descriptive Statistics Market Conditions Of the nine deals we highlight, three were transacted in volatile markets and six took place in calm markets with market indexes trading at or near their highs. There is a noticeable difference between the initial market conditions of transactions announced in the latter half of 2000 and the initial conditions of those announced in September and October 2001. The AXA Financial, Hertz, Infinity, Delhaize and Avis offers were all announced when the S&P 500 index was trading near its all-time high levels and market volatility was low.8 The TyCom, Prodigy, and TD Waterhouse offers, on the other hand, were announced following the terrorist attacks of September 11 in a period of high market volatility. Based on previous observations, it also appears that depressed market conditions give opportunity for a higher initial premium.

We use the CBOE S&P 100 Volatility Index (VIX) as a measure of market volatility. The VIX index reflects a market estimate of future volatility, based on the "at the money" quotes of S&P 100 index options. January 3, 2002

15

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 5: Market Volatility (CBOE S&P 100 Volatility Index -- VIX) and S&P 500 Levels

Late 2000/Early 2001 Transactions (6) 22.5 29.5 1466.81 Recent Transactions (3) 40.5 35.5 1039.69

VIX at Announcement (One-Month Average) VIX at Bump (One-Week Average) S&P 500 Index Level Source: Lehman Brothers.

As can be seen in Figure 5, the one-month VIX index pre-announcement average for the offers announced in late 2000/early 2001 was 22.5, whereas the VIX average for the recent transactions was 40.5. The average S&P 500 index level was close to the alltime high of 1527.46 for the former transactions, while it was close to two-year lows for the latter transactions. Timing of Bumps On average, the acquirer raises its offer two months after announcement. This average duration disguises the difference between transactions announced recently and those announced late in the year 2000. As can be seen in Figure 6, the bump in the terms of offers made public following the September 11 attacks came after an average of 20 days. This timing contrasts sharply with that for the transactions announced late 2000/early 2001, where the bump materialized almost three months after the announcement on average. The quick resolution of the deals announced after September 11 may have been partly induced by a shift of negotiating power from the seller to the buyer in a declining market. Unfortunately, we cannot isolate the impact of this effect from the impact of using a tender offer structure, since the acquirers bypassed the target board in two of the three deals announced after September 11. Figure 6: Average Time to Bump

All Days to Bump 62 Late 2000/Early 2001 84 Recent 20 Cash 70 Stock 54

Source: Lehman Brothers.

Premiums Our results suggest that acquirers may have been able to afford larger premiums in recent transactions partly because of the large decline in target prices over the threemonth period preceding deal announcement. Similarly, the acquirers may have paid relatively lower premiums in transactions of late 2000/early 2001 partly because of rising target prices (on average) in the period preceding deal announcements. We describe our methodology and present our results below. We caution, however, that the results in this section should not be interpreted as generalizations across minority squeeze outs because our sample size is small.

16

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

We calculate the premium offered to the target using four different time periods for preannouncement prices--one day, one week, one month, and three months. In cash transactions, the target price is averaged over the relevant time period before announcement, and the premium is calculated with respect to that average price. The one-day premium is simply with respect to target stock closing price before the announcement of the deal. In stock transactions, both the acquirer and target prices are averaged over the relevant time periods before the announcement and the premium is calculated using these average prices and the relevant exchange ratio. We calculate the premium based on both the initial and final terms of a deal. Our results for individual deals are reported in Figure 29. In this section, we focus on sample averages. Figure 7 displays the results from the average premium analysis. Figure 7 Equal-Weighted Premium Summary for Highlighted Transactions

Premium over PreAnnouncement Prices One-Day One-Week Average One-Month Average Three-Month Average Source: Lehman Brothers. All Transactions (9) Initial Offer 25.2% 26.3% 24.3% 18.7% Final Offer 40.8% 41.5% 39.0% 33.3% Late 2000/Early 2001 Transactions (6) Initial Offer Final Offer 15.9% 17.7% 23.2% 27.1% 34.6% 36.3% 42.4% 46.9% Recent Transactions (3) Initial Offer 49.0% 49.4% 34.3% 10.9% Final Offer 64.8% 64.2% 46.4% 21.7%

For all transactions, the average premium based on a one-day to one-month timeframe for prices is in the range of 24%-26%. The premium based on three-month average prices is lower at approximately 19%. The premium based on the final terms is in the range of 39%-42%, once again for the one-day to one-month timeframe. The premium based on three-month average prices is at 33%. On average, the increase in the offer is approximately 15 percentage points. When we break down our sample into two based on the period of announcement, we see that there is a dichotomy in terms of premiums offered. For instance, transactions announced in late 2000/early 2001 enjoy an average premium (based on one-week average prices) of 17.7% and this premium is eventually raised to 36.3%. The initial average premium in recent transactions is considerably larger at 49.4% and is eventually raised to 64.2%. The discrepancy across these transactions possibly reflects the depressed levels the target stocks were trading at. The "term structure" of premiums reveals an interesting pattern across these two groups. For transactions announced in late 2000/early 2001, the calculated premium is smaller for averaging periods that approach the time of announcement. This pattern is in sharp contrast to that seen in recent transactions in which the calculated premium is larger over averaging periods closer to the time of deal announcement. We also find that cash transactions have a larger increase in the offer than stock transactions, with the average percentage point increase in cash transaction is almost twice as large as that in stock transactions. In Figure 8, we break our sample into two

January 3, 2002

17

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

groups based on the form of consideration.

We exclude the AXA Financial/AXA

transaction because its terms include both cash and stock. In our sample, the initial oneday premium is slightly larger for cash transactions, but the initial premium measured over one week to three months is higher in stock transactions. The final premiums appear comparable between stock and cash transactions over one -week to three-month timeframes, although the cash transactions have a larger one-day final premium than stock transactions. Figure 8: Equal-Weighted Premium Summary for Highlighted Cash and Stock Transactions

Premium over PreAnnouncement Prices One-Day One-Week Average One-Month Average Three-Month Average Source: Lehman Brothers. Cash Transactions (5) Initial Offer 29.0% 24.9% 20.8% 15.7% Final Offer 48.8% 43.9% 38.5% 33.4% Stock Transactions (3) Initial Offer 26.3% 35.5% 33.1% 20.5% Final Offer 36.7% 45.9% 43.7% 30.2%

In order to provide a point of reference and give a sense of how our results compare to those obtained in larger samples, we also highlight external research on minority squeeze -out premiums. The AXA registration statement filed on November 21, 2000, with the SEC on form F-4 included a premium analysis of minority squeeze-out transactions. This analysis was conducted by the financial advisor to the AXA Financial special committee. The advisor reviewed 79 minority squeeze -out transactions of $50 million or more in value, announced between January 1, 1992 and July 21, 2000. Five of the transactions had value in excess of $1 billion and 20 transactions involved stock as part of the merger consideration. The advisors analyzed the consideration received in each of the precedent minority purchase transactions to derive the final premiums paid over the public trading prices five trading days and 20 trading days prior to the announcement of the transaction. Figure 9 presents the results of this analysis. Figure 9: Final Premium Analysis (AXA Registration Statement)

Premium over Average Price (Five Trading Days Prior to Announcement) Mean Median All Transactions 33.2% 25.3% Premium over Average Price (Twenty Trading Days Prior to Announcement) Mean Median 37.8% 31.9% 18.3% 29.3%

Stock Transactions 15.5% 14.3% 19.8% Transactions over $1 22.1% 22.8% 28.8% Billion Source: AXA Registration Statement (Form F-4), November 21, 2000.

In this sample, the average final premiums over the week and month before transaction announcement are 33.2% and 37.8%, respectively. These estimates are lower than our calculated premiums of 41.5% and 39.0% over the week and month before announcement, respectively (see Figure 7). We note that our one-week results may be biased up because of the large premiums paid in recent transactions. Without the recent

18

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

transactions, our average final premium decreases to 36.3% using one-week average prices. For stock transactions, we believe that our sample is too small to make a meaningful comparison. Overall, our findings do not diverge significantly from these larger-sample results. Future Minority Squeeze-Outs? Based on our analysis of minority squeeze -outs, we have observed that recent transactions were initiated following significant decline in the price of a subsidiary that was previously carved out of the acquirer. In Figure 10, we list seven potential minority squeeze -out situations based on how recently the carve-out took place and whether the subsidiary is trading near its lows since the IPO. Figure 10: Potential Minority Squeeze-Outs

Parent Name Subsidiary Name Economic % Owned IPO date Value of Change in Change in SPX Minority Shares Subsidiary Price since IPO ($ mill) since IPO 121 175 282 150 106 1,691 192 -20.0% -21.6% -44.0% -92.2% -95.6% -49.3% -42.0% -20.5% -21.7% -14.1% -11.8% -8.1% -14.8% -22.1%

SPX Corp Sea Containers DTE Energy Barnes & Noble UnitedGlobalCom Nextel Communications AOL Time Warner Source: Lehman Brothers.

Inrange Technologies Orient Express Hotels Plug Power Barnesandnoble.com United Pan-Europe Comm Nextel Partners America Online Latin America

89.5% 63.0% 31.8% 36.2% 52.4% 33.0% 38.0%

21-Sep-00 9-Aug-00 28-Oct-99 24-May-99 11-Feb-99 22-Feb-00 7-Aug-00

The risk in using this criterion is that that the parent may just as well decide to complete the divestiture of a previously carved-out subsidiary, rather than purchasing the minority shares, even following a significant price decline since the IPO. For example, on November 29, 2001, FMC Corporation announced plans to complete the spin-off of FMC Technologies, which was carved out on June 13, 2001. This situation would have been on our list of potential squeeze-out candidates based on our selection criteria. The spin-off of a subsidiary may serve to put further downward pressure on its price, leading investors to incur losses from trading strategies based on the expectation of a squeeze out.9 A significant decline in a subsidiary stock price may not necessarily imply an increased likelihood of a squeeze-out if the market conditions also deteriorate. The acquirer may not view such a decline as an opportunity to consolidate ownership in its subsidiary. While Inrange stock price has declined by 20% since the IPO, the S&P 500 index has also declined by 20.5%. Similarly, the decline in the price of Orient Express Hotels stock is in line with the decline in the S&P 500 since the time of the IPO.

See our Spin-Off Study: Performance Post Spin for the effects of a spin-off on the near-term performance of the parent and the subsidiary. We find that spinning off a major subsidiary is a positive catalyst for the parent company and a negative catalyst for the subsidiary. January 3, 2002

19

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

What is the Probability of a Bump? Probability Analysis in Minority Squeeze-Outs Synopsis of Framework and Main Assumptions We use a simple risk-reward framework to estimate the probability of a bump using the risk arbitrage spread in minority squeeze -outs. Our framework is described in technical detail in the Appendix. The following formula forms the basis of our calculations:

P( b ) =

PtT rt [pSP + (1 p )DS t ] t [p 2USt + (1 p 2 ) DSt ] [p SPt + (1 p) DSt ]

This formula implies that the probability of a bump ( (b)) depends primarily on the P following factors: 1. Current risk arbitrage spread ( SPt ) 2. Downside if deal breaks ( DS t ) 3. Expected cash or stock consideration following the bump (this variable factors in through US t , the upside if there is a bump) 4. Current target stock price ( PtT ) 5. Alternative rate of return on investment ( rt ) until the expected time of bump. 6. Acquirer and target share prices at the time of the bump (these variables factor in through US t ) 7. Expected dividends until the time of bump 8. Probability of deal completion conditional on a bump in terms ( p 2 ) 9. Probability of deal completion conditional on no bump in terms ( p ) Only the current risk arbitrage spread and the current target stock price are known variables at the time of estimation. We need to either estimate the remaining variables or make assumptions about their values. Therefore, the estimation of the probability of a bump is a subjective exercise that depends on how closely our assumptions approximate reality. In most of our calculations, deal break -up values for the target and acquirer stocks are based on specified pre-announcement trading levels adjusted by the change in the S&P 500 index according to the relevant betas. In a few cases in which this method does not produce meaningful results, we use alternative methods based on initial arbitrage

20

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

impact. Given that the time to bump is relatively short in many transactions, we believe that these methods are sufficiently reliable. We also make the simplifying assumptions that the markets expectation of the value of the bump and its timing are in fact accurate ex post: the acquirer eventually raises its offer to reflect the markets expected value of a bump at the time predicted by the market. Consequently, the probability that we estimate should be interpreted as the probability of a bump of a given size. We assume that there is minimal regulatory risk such that the arbitrage spread essentially collapses to zero at the time of the bump announcement. This assumption is quite reasonable. In many cases, the target and the acquirer are in different lines of business. In other cases, the investment of the acquirer in the target has been in place for a long period of time and likely has passed regulatory muster. In reality, arbitrage spreads narrow to unattractive levels following a bump, and we presume that arbitrageurs unwind their positions to pursue investment opportunities elsewhere. The acquirer prices at the time of a bump are assumed to be equal to current levels adjusted for any dividend payments. Finally, we assume that the probability of deal completion conditional on a bump is one: the deal is certain to go through following a bump in the terms. This assumption is consistent with the assumption of minimal regulatory risk and is predicated on similar reasoning. We do not make assumptions about the probability of deal completion conditional on the terms remaining the same, but rather display results for varying values of this probability.10 If there is no bump in the terms, the board of directors of the target may find it in its shareholders best interest to reject the offer. The boards proclivity to reject the offer may depend on a number of factors such as the targets business outlook on a standalone basis, availability of alternative bidders, and the boards negotiating position. Results Nine of the following 18 figures (Figures 11-28) trace out the risk arbitrage spread according to both the initial and final terms of deals. The spread using the final terms is calculated from one month before the announcement until the announcement of a bump. At the time of the bump, the two spreads converge as we apply the final terms to both.

10

We have some preliminary information on conditional probabilities of deal outcomes and bumps. We looked at 34 all-cash all-U.S. minority squeeze-outs announced between 1989 and 2000. Of these, 21 (61.8%) were completed with a bump, six (17.6%) were completed without a bump, and seven (20.6%) were terminated without a bump. Two of the seven deals terminated without a bump had initial acquirer ownership of target shares of 80% or more. Two of the six deals completed with a bump had initial acquirer ownership of target shares of 80% or more. Based on this information: (i) conditional on no bump, sample probability of deal termination is 54%; (ii) conditional on a bump, sample probability of deal completion is 100%; (iii) conditional on no bump and initial ownership exceeding 80%, the sample probability of deal termination is 50%. These results suggest that deal completion is a coin flip without a bump and practically a certainty wi th a bump. But since our sample is not very large, we would not generalize these results. January 3, 2002

21

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

The remaining nine figures display our calculations of the probability of a bump from the time of deal announcement until the time of the bump as a function of the probability of deal completion conditional on the terms remaining the same. Juxtaposing the behavior of the spread and the probability is useful for highlighting the relationship between the two variables. We make several observations from these figures. Below, we note these observations and also indicate generalizations we derive using the formula for the probability of a bump:11 1. More negative arbitrage spreads tend to be associated with higher estimated probabilities of a bump in deal terms. The behavior of the spread and the probability in the Hertz/Ford transaction (see Figure 13 and Figure 14) display this result very clearly (also visible in Prodigy/SBC, TD Waterhouse/Toronto-Dominion Bank figures). The initially negative spread in Hertz/Ford became increasingly negative over time. At the same time, the probability of a bump increased from around 60% initially (for a p of 0.5) to approximately 90% at the time of the final offer. Generally, as long as the expected upside from a bump in the terms more than compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital, lower (or more negative) arbitrage spreads imply higher probabilities of a bump, with all else the same. A negative spread implies that investors incur an immediate loss by entering into a risk arbitrage position. In order to be willing to invest, arbitrageurs need to be ever more confident of a bump in the terms, the more initial loss they incur. 2. The estimated probability of a bump is generally higher, the smaller the expected bump built into our calculations. This type of result may be seen in the TyCom/Tyco transaction in which the final offer was not significantly higher than the initial offer. In this situation, the spread, while negative, was not wide in absolute terms. Despite such spread behavior, there was still a fairly high expectation of a small bump. If we assume that the deal completion probability in the absence of a bump was fairly high, for example 75%, Figure 24 indicates that the probability of a bump (exchange ratio rising from 0.2997 TYC shares to 0.3133 TYC shares) ranged between 70% and 80%. In a typical minority squeeze-out situation in which the initial spread is negative (or positive, but narrow) and risk arbitrageurs stand to incur losses upon deal termination, a lower expected bump implies a higher probability of a bump, all else equal. In other words, if investors expect a small bump, they need to be highly confident that such a bump will materialize in order to invest in the transaction.

11

Note that not all of our results may be directly observable from the figures.

22

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

3. Even positive arbitrage spreads may be associated with a positive probability of a bump. This result can be seen in Figure 15 and Figure 16, which display the spread and probability of a bump for the Infinity/Viacom transaction. While the spread traded mostly positive near the closing of the transaction, the estimated probability was still fairly high. This finding is primarily driven by the extent of potential loss upon deal termination. We can verify that as long as the expected upside from a bump in the terms more than compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital, the greater the expected loss upon deal termination, the more positive (or less negative) the spread needs to be for investors to be willing to put on a risk arbitrage position, with all else the same. A corollary of this result is that, for a given probability of a bump, investors need to be compensated with a wider spread as the expected loss upon deal termination increases. 4. The behavior of the spread at the time of the bump reveals the surprise element in a bump. In the Hertz/Ford transaction, for example, the spread appears to have behaved as if the final offer would in fact be $35.50: we observe a big jump in the spread as calculated using the initial terms whereas the spread according to the final terms narrows only slightly. This behavior is confirmed by the fairly high probability of a bump just before the final terms are announced. We can see a similar pattern in the Prodigy/SBC and TD Waterhouse/Toronto-Dominion Bank transactions also. In contrast, the moderate to sharp narrowing of the spread as calculated using the final terms in Avis/Cendant, Sodexho Marriott/Sodexho Alliance, AXA Financial/AXA and Infinity/Viacom transactions reveals that the final terms were not expected with great certainty. This behavior is also confirmed by the moderate estimated probabilities of bump in these transactions. Figure 11: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until BumpAXF/AXA

60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10%

9/8 /00 10 /20 /00 11 /17 /00 12 /1/ 00 8/2 5/0 0 7/2 8/0 0 8/1 1/0 0 9/2 2/0 0 10 /6/0 0 11 /3/0 0 12 /15 /00 12 /29 /00

Announcement

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

January 3, 2002

23

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 12: Probability of a BumpAXF/AXA

100% p=0.25 80% 60% 40% 20% 0%

9/4 /00 8/3 0/0 0 9/9 /00 9/1 4/0 0 9/1 9/0 0 9/2 4/0 0 9/2 9/0 0 10 /4/ 00 10 /9/ 00 10 /14 /00

p=0.5

p=0.75

Source: Lehman Brothers.

Figure 13: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump HRZ/F

50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10% -20%

9/4 /00 9/1 8/0 0 10 /2/ 00 10 /16 /00 10 /30 /00 11 /13 /00 11 /27 /00 12 /11 /00 12 /25 /00 1/8 /01 1/2 2/0 1 2/5 /01 2/1 9/0 1

12 /30 /00

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Announcement

3/5 /01

p=0.75

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

Figure 14: Probability of a BumpHRZ/F

100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40%

9/2 1/0 0 10 /1/ 00 10 /11 /00 10 /21 /00 10 /31 /00 11 /10 /00 11 /20 /00 11 /30 /00 12 /10 /00 12 /20 /00 1/9 /01

8/2 1/0 0

p=0.25

p=0.5

Source: Lehman Brothers.

24

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 15: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump INF/VIA

20% % Spread (Initial Offer) 15% 10% 5% 0% Announcement -5%

7/1 7/0 0 8/2 8/0 0 9/1 8/0 0 10 /9/ 00 1/1 /01 8/7 /00 1/2 2/0 1

3/2 6/0 1

% Spread (Final Offer)

10 /30 /00

11 /20 /00

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

Figure 16: Probability of a BumpINF/VIA

100% 80% 60% 40% 20% p=0.25 0%

8/1 5/0 0 8/2 2/0 0 8/2 9/0 0 9/5 /00 9/1 2/0 0 9/1 9/0 0 9/2 6/0 0 10 /3/ 00 10 /17 /00 10 /24 /00

4/1 6/0 1

p=0.5

p=0.75

Source: Lehman Brothers.

Figure 17: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump DZA/DELB

80% Announcement 60% 40% 20% 0% -20%

1/ 1/ 01 8/7 /00 12 /11 /00 8/2 8/0 0 10 /9/ 00 10 /30 /00 11 /20 /00 2/1 2/0 1 9/1 8/0 0 1/2 2/0 1 3/5 /01

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

10 /10 /00

12 /11 /00

2/1 2/0 1

January 3, 2002

25

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 18: Probability of a BumpDZA/DELB

100% p=0.25 80% p=0.5 p=0.75

60%

40%

20%

9/7 /00 9/1 4/0 0 9/2 8/0 0 10 /5/ 00 11 /2/ 00 9/2 1/0 0 10 /19 /00 10 /26 /00 11 /9/ 00 11 /16 /00 10 /12 /00

Source: Lehman Brothers.

Figure 19: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump AVI/CD

60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10%

8/4 /00 7/1 4/0 0 8/2 5/0 0 9/1 5/0 0 10 /6/ 00 12 /8/ 00 12 /29 /00 10 /27 /00 11 /17 /00 1/1 9/0 1

10 /24 /00

Announcement

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

Figure 20: Probability of a BumpAVI/CD

100% 80% 60% 40% 20% p=0.25 0%

8/1 5/0 0 8/2 5/0 0 9/4 /00 10 /14 /00 11 /3/ 00 9/1 4/0 0 9/2 4/0 0 10 /4/ 00

p=0.5

p=0.75

Source: Lehman Brothers.

26

January 3, 2002

2/9 /01

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 21: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until BumpSDH/SW

60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10% -20%

1/ 9/ 01 1/2 3/0 1 2/2 0/0 1 5/ 1/ 01 2/6 /01 3/6 /01 4/3 /01 5/1 5/0 1 5/2 9/0 1 12 /26 /00 6/1 2/0 1

p=0.75

4/2 5/0 1

Announcement

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

3/2 0/0 1

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

Figure 22: Probability of a BumpSDH/SW

80% p=0.25 70% p=0.5

60%

50%

40%

3/6 /01 2/4 /01 1/2 5/0 1 2/1 4/0 1 3/1 6/0 1 3/2 6/0 1 4/5 /01 4/1 5/0 1 2/2 4/0 1

Source: Lehman Brothers.

Figure 23: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump TCM/TYC

80% Announcement 60% 40% 20% 0% -20%

9/7 /20 01 9/4 /20 01 9/1 8/2 00 1 9/2 1/2 00 1 9/2 6/2 00 1 10 /9/ 20 01 10 /12 /20 01 10 /17 /20 01 10 /22 /20 01 10 /1/ 20 01 10 /4/ 20 01

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

4/1 7/0 1

January 3, 2002

27

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 24: Probability of a BumpTCM/TYC

90%

70%

50% p=0.5 30%

10 /4/2 00 1 10 /5/2 00 1 10 /8/2 00 1 10 /9/2 00 1 10 /10 /20 01 10 /11 /20 01 10 /15 /20 01 10 /17 /20 01 10 /12 /20 01 10 /16 /20 01 10 /18 /20 01

p=0.75

p=0.9

Source: Lehman Brothers.

Figure 25: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump PRGY/SBC

80% 60% 40% 20% 0% Announcement -20%

8/2 1/0 0 8/2 6/0 0 8/3 1/0 0 9/5 /00 9/1 0/0 0 9/1 5/0 0 9/2 0/0 0 9/2 5/0 0 9/3 0/0 0 10 /5/ 00 10 /10 /00

p=0.75

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

Figure 26: Probability of a BumpPRGY/SBC

100% 80% 60% 40% p=0.1 20%

9/2 4/2 00 1 9/2 6/2 00 1 9/2 8/2 00 1 10 /2/2 00 1 10 /4/2 00 1 10 /8/2 00 1 10 /16 /20 01 10 /10 /20 01 10 /12 /20 01

p=0.5

Source: Lehman Brothers.

28

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Figure 27: Spread Behavior under Initial and Final Terms until Bump TWE/TD

60% 40% 20% 0% -20%

9/1 0/2 00 1 9/1 9/2 00 1 9/2 4/2 00 1 9/2 7/2 00 1 10 /2/2 00 1 10 /5/ 20 01 10 /10 /20 01 10 /15 /20 01 10 /18 /20 01 10 /23 /20 01 10 /26 /20 01 10 /31 /20 01

Announcement

% Spread (Initial Offer) % Spread (Final Offer)

Source: Lehman Brothers, Bloomberg.

Figure 28: Probability of a Bump TWE/TD

100%

90%

80% p=0.25 70%

10 /11 /20 01 10 /17 /20 01 10 /19 /20 01 10 /25 /20 01 10 /29 /20 01 10 /15 /20 01 10 /23 /20 01

p=0.5

p=0.75

Source: Lehman Brothers.

January 3, 2002

29

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Conclusion Delaware courts apply the entire fairness test in reviewing decisions of directors in minority squeeze -outs. The target board typically hires a special committee of independent directors to evaluate the acquirers offer in a manner that satisfies the legal criteria associated with the entire fairness test. The acquirer may conduct a tender offer rather than take its offer directly to the target board so as to exert some timing and pricing discipline on the evaluation process. We witness this structure in two of the deals we highlight, Prodigy/SBC and TD Waterhouse/Toronto Dominion. We find that the initial premiums in transactions in which the targets were trading near their lows tend to be relatively high. Conversely, the initial premiums for targets with preannouncement prices near their highs appear to be relatively low. We do not detect a relationship between the size of the bump and the initial premium. We find some suggestive evidence that acquirers may have more incentive to negotiate with the board when shareholding is concentrated, raising the likelihood of successful opposition. We also note a possible sense of urgency in transactions announced shortly after the September 11 attacks. The time to bump in recent transactions is significantly less than those announced in late 2000. In two of these recent deals, the acquirer has also adopted the tender offer structure, possibly facilitating the negotiation process in a down market. Based on our premium analysis, it appears that acquirers were able to afford larger premiums in recent transactions partly because of the large decline in target prices over the three-month period preceding deal announcement. In our sample, cash transactions have a larger increase in the offer than stock transactions. We caution, however, that our sample size is too small to make generalizations and that our evidence is anecdotal. Our probability analysis leads us to the followings conclusions: 1. As long as the expected upside from a bump in the terms more than compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital, lower (or more negative) arbitrage spreads imply higher probabilities of a bump, all else being equal. 2. In a typical minority squeeze -out situation in whichthe initial spread is negative (or positive, but narrow) and risk arbitrageurs stand to incur losses upon deal termination, a lower expected bump implies a higher probability of a bump, all else being equal. 3. As long as the expected upside from a bump in the terms more than compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital, the greater the expected loss upon deal termination, the more positive (or less negative) the spread needs to be for investors to be willing to put on a risk arbitrage position, all else being equal.

30

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

These points highlight the inverse relationship between probability of a bump and the spread, the inverse relationship between the probability of a bump and the level of the expected bump, and the positive relationship between expected loss and the spread.

January 3, 2002

31

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

32

January 3, 2002

Figure 29: Individual Characteristics of Highlighted Transactions

AXA Financial Deal Duration (Days) Time to Bump (Days) Form of Payment % Acquired Transaction Value (millions, original) Transaction Value (millions, amended) Transaction Value/Acquirer Market Cap Initial Premium (1-Day) Final Premium (1-Day) Initial Premium (1-Week) Final Premium (1-Week) Initial Premium (1-Month) Final Premium (1-Month) Initial Premium (3-Month) Final Premium (3-Month) Change in Target Price (3 Months to Announcement) VIX Index at Announcement (1-Month Average) VIX Index at Bump (1-Week Average) S&P 500 Level (At Announcement) 129 49 Stock & Cash 39.7% 9,206 9,399 14.3% 2.4% 13.0% 5.8% 16.8% 15.8% 27.9% 28.6% 41.9% 26.4% 20.7 32.1 1509.84 Hertz 170 118 Cash 18.5% 597 706 2.3% 23.7% 46.4% 21.7% 44.0% 7.8% 27.5% 0.1% 18.4% -19.3% 20.7 28.6 1451.34 Infinity Broadcasting 193 77 Stock 35.7% 15,581 12,799 11.9% 13.6% 19.2% 11.5% 17.0% 9.4% 14.9% 7.7% 13.1% 6.8% 22.1 29.1 1491.56 Delhaize America 232 71 Stock 55.0% 1,863 1,846 37.5% 17.3% 36.2% 24.4% 42.2% 33.5% 52.6% 28.4% 46.7% -16.1% 20.3 29.4 1492.25 Avis Group 199 90 Cash 82.0% 787 896 9.3% 13.7% 29.4% 18.7% 35.0% 26.1% 43.5% 40.3% 59.6% 19.6% 22.1 29.8 1491.56 Sodexho Marriott Services 148 97 Cash 52.0% 899 1,066 14.5% 8.5% 28.6% 6.6% 26.3% 23.4% 45.7% 30.7% 54.9% 31.8% 29.0 28.2 1364.30 TyCom 76 15 Stock 11.0% 784 864 1.0% 48.0% 54.7% 70.7% 78.5% 56.5% 63.6% 25.3% 30.9% -42.1% 37.6 37.4 1072.28 Prodigy 45 24 Cash 58.0% 384 465 0.3% 54.0% 86.4% 38.5% 67.8% 5.6% 27.9% -2.6% 18.0% -15.3% 45.6 36.7 965.80 TD Waterhouse 49 20 Cash 12.0% 409 431 2.8% 45.2% 53.2% 38.9% 46.4% 40.9% 47.8% 9.9% 16.1% -37.1% 38.4 32.5 1080.99

Notes: Amended transaction values are calculated based on the relevant prices at the time of amendment. VIX index levels are calculated as averages over the specified time period before either the announcement or the bump. The methodology for the premiums is described in the main body of the report. Source: Lehman Brothers.

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Appendix Probability Framework In this appendix, we lay out our framework for calculating the probability of a bump. To begin, we assume that there are four possible outcomes of a minority squeeze-out: 1. The terms are unchanged and the deal is completed. This event happens with joint probability P(c , nb) . 2. The terms are unchanged and the deal is terminated. This event happens with joint probability P(t , nb) . 3. There is a bump and the deal is completed. This event happens with joint probability P(c , b) . We assume that the bump is of a given size for simplicity. 4. There is a bump and the deal is terminated. This event happens with joint probability P(t , b) . Given these outcomes and the joint probabilities, the following relationships must hold: The probabilities of the joint outcomes must sum to one.

P(c , nb) + P(t , nb) + P(c , b) + P (t , b ) = 1

Conditional probabilities of deal completion/termination must sum to one.

P(c | nb) + P(t | nb) = 1 P(c | b ) + P (t | b) = 1

And finally, the probability of a bump and the probability of no bump must sum to one.

P( nb) + P (b) = 1

We also define the following terms: Risk arbitrage spread:

SP = (PtA d A ) (PtT d T ) + C t

is the original exchange ratio. d A and d T are present values of cumulative acquirer

and target dividends until the time of bump, respectively. C is the original cash consideration. PtA and PtT are the current acquirer and target prices, respectively.

January 3, 2002

33

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

Upside if there is a bump:

USt = PtA PtT + ( n ) PtAk + d T n d A + Cn +

n is the new exchange ratio and C n is the new cash consideration accompanying a

bump. PtAk is the acquirer price at the time of the bump. This formulation assumes that + the risk arbitrage spread collapses to zero at the time of the bump. Downside if the deal breaks:

A T DSt = (PtA PD ) + ( PtT PD )

A T PD and PD are acquirer and target prices upon deal termination.

Risk/Reward: Assuming that investors are risk-neutral, they set the expected return on the investment equal to a risk-free or a low-risk return:

P(c, nb) SP + P (t, nb)DSt + P (c,b )USt + P(t , b) DSt = PtT rt t

It is assumed that the initial investment is equal to the target price and the alternative rate of return is rt . After conditioning out the outcomes bump and no bump, we can transform this equation in the following manner:

P(c | nb)P(nb)SP + P(t | nb)P( nb)DSt + P(c | b)P(b)USt + P(t | b )P(b) DSt = PtT rt t

After substituting in the second and third probability relationships defined above and rearranging the risk/reward equation, we obtain the following formula for the probability of a bump P(b ) :

P( b ) =

where

PtT rt [pSP + (1 p )DS t ] t [p 2USt + (1 p 2 ) DSt ] [p SPt + (1 p) DSt ]

p 2 = P(c | b ) (probability that the deal is completed given that there is a bump) and p = P(c | nb) (probability that the deal is completed given that there is no bump).

In our calculations, we assume that p 2 is equal to one so that the formula for the probability of a bump simplifies further to:

34

January 3, 2002

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

P( b ) =

Trading Considerations Squeeze-Out Announcement

PtT rt [pSPt + (1 p ) DSt ] USt [pSP + (1 p) DS t ] t

In many minority squeeze-out situations, following the announcement of the transaction, the target price trades through the offer in expectation of a bump in the terms. Hence, the risk arbitrage spread is initially negative. Arbitrageurs are active buyers of the target upon announcement of the offer if they expect the offer to be raised. This requires that they put up capital, which is justified by the anticipation of a bump and its magnitude. Fundamental accounts may also increase their holdings to the extent that they believe the offer undervalues the company. Index accounts are not active in the market since the target is not a part of a major S&P index (because of its small float relative to shares outstanding). In stock transactions, the acquirer is typically subject to downward price pressure as arbitrageurs set up positions. Figure 30 reports the acquirer price reactions to deal announcements in our sample. On average, the decline in the acquirer price 5% over the week following announcement. Figure 30: Acquirer Price Reaction to Squeeze-Out Announcement

AXF/AXA 1-Day 1-Week 2-Weeks -7.7% -9.4% -9.2% INF/VIA -2.3% -3.7% -4.4% DZA/DELB -6.0% -7.2% -9.2% TCM/TYC 1.6% 0.5% 1.9% Average -3.6% -5.0% -5.2%

Notes: The weight of the AXF/AXA transaction in the average is based on the stock portion of the transaction. Source: Lehman Brothers.

Announcement of Bump When a bump is announced, the price moves to a level that is less than the value of the new offer. This may be below or above its pre-bump level depending on the price reaction of the acquirer in a stock deal. The risk arbitrage spread turns positive, but is typically very narrow. Many arbitrageurs may unwind their positions because the spread after the bump is generally not attractive enough to justify the commitment of capital for the rest of the deal. Fundamental accounts may or may not sell depending on their willingness to hold the acquiring company (in stock exchange offers) and on tax considerations. Index accounts are not active in the market. From Bump to Deal Closing The spread continues to narrow until the deal closes. The spread is typically not attractive enough for arbitrageurs. At the time of deal closing, there would be indexrelated (S&P indexes) buying of acquirer shares if the number of acquirer shares to be

January 3, 2002

35

Understanding Minority Squeeze-Outs

issued exceeds 5% of those outstanding. There is typically no index activity on the tar get side.

36

January 3, 2002

GLOBAL EQUITY DERIVATIVES

Equity Derivatives and Quantitative Research

Global Head of Derivatives and Quantitative Research

New York Gabriela Baez Alex E. Budny Claire W. Chan Evren Ergin, Ph.D. James J. Hosker Sugun V. Kapoor Paul K. Lieberman Andrew Whittaker London Murali Ramaswami, Ph.D .............................. 1.201.524.2568............................. mramaswa@lehman.com

New York 101 Hudson Street Jersey City, NJ 07302 USA 1.201.524.2568

London One Broadgate London EC2M 7HA England 44.20.7256.4275

Head of European Derivatives and Quantitative Research

John Carson William Hunter Nicolas Karageorgis Tai-Mey Lim Nicolas J. Mougeot, Ph.D. Roberto Torresetti

Andrew R. Harmstone ................................ 44.20.7256.4275................................aharmsto@lehman.com

Tokyo 12-32 Akasaka 1-chome Minato-ku Tokyo 107 Japan 813.5571.7357

Tokyo Lici Wu ..................................................... 81.3.5571.7468....................................... lwu@lehman.com Equity Derivatives Sales New York .................................................. 1.201.524.2565 Boston ....................................................... 1.617.330.5972 Chicago .................................................... 1.312.609.8174 London .................................................... 44.20.7260.3070 Frankfurt.49.69.15307.7100 Tokyo .............................................. 81.3.5571.7330/7454 Zurich ......................................................... 41.1.287.8989

Hong Kong One Pacific Place 88 Queensway, Hong Kong 852.2869.3000