Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Archaeology in Haliburton

Uploaded by

dudmanlakeOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Archaeology in Haliburton

Uploaded by

dudmanlakeCopyright:

Available Formats

A Brief Survey of Archaeology in Haliburton County and Vicinity: Observations and Comment

Tom Ballantine, Haliburton Museum

ABSTRACT Haliburton County is located on the south slope of the Algonquin Dome. The headwaters of the Oxtongue, the Black, the Gull, the Madawaska, and the York rivers all find their origins within Algonquin Park or no more than a short portage away. Several additional streams such as the Drag, Irondale and Burnt rivers also find their origins within the highlands of Haliburton County. This brief survey of selected sites and associated cultural material provides a useful introduction to the region and provides insight for students of the archaeology of both Algonquin Park and the Ottawa River Valley RSUM Le comt de Haliburton est situ sur le versant sud du massif Algonquin. Le cours suprieur des rivires Oxtongue, Black, Gull, Madawaska et York trouvent toutes leur origine dans le parc Algonquin ou une courte distance de portage. Plusieurs autres cours deau, tels que les rivires Drag, Irondale et Burnt, prennent aussi leur source dans les hauteurs du comt de Haliburton. Cette brve enqute sur certains sites et les biens culturels qui y sont associs fournit une introduction utile sur la rgion et donne un aperu aux tudiants en archologie la fois du parc Algonquin et de la valle de la rivire des Outaouais.

This brief overview of archaeological work in Haliburton County is not meant to be comprehensive. It is offered as an introduction to the resources of the area that is a neighbour to Algonquin Park and as such is useful for purposes of comparison. Much of the area to the south of the Highway 60 corridor which runs through the park was once associated with or belonged to Haliburton County. The Haliburton trappers of old often forayed into the park after its creation following routes that had been established long ago. History of Archaeological Work David Boyle of the Provincial Museum presented the first formal report on archaeology in the vicinity of Haliburton County in 1891 (Boyle 1891). The work he recounted was actually conducted in neighbouring Hastings County, at Baptiste Lake whose headwaters arise in Haliburton County. He and his companions visited a small native community under the leadership of Francois Antoine (Ag-wah-setch). The party visited a few spots on the lake including Grassy Point where a number of artifacts had been recovered. It was apparent to Boyle that this was an important location on the lake. He mentions that a prized copper specimen had been found at this place and been contributed to the museums collection. Both Boyles article and a short ethnographic piece by A.F. Chamberlain entitled The Algonkian Indians of Baptiste Lake (Chamberlain 1891) relate interesting cultural and linguistic anecdotes relating to beliefs, place names, and canoe building.

Supplement to Partners to the Past: Proceedings of the 2005 Ontario Archaeological Society Symposium Edited by James S. Molnar Copyright 2008 The Ottawa Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society ISBN 978-0-9698411-3-5

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________ This brief expedition was conducted in September of 1890. This type of adventure was usually spurred on by reports of finds made in areas that were opening up for settlement or meeting the woodsmans axe. Compilations of information related to local finds appear in the popular centennial histories published throughout the region. Haliburton is no exception. Nila Reynolds history In Quest of Yesterday provides information about the location of numerous native sites rediscovered and reported by local informants. It is apparent that a number of these locations were the habitual campsites of native families exploiting the resources of the area. It seems that some of the initial settlers in the area tended to usurp the ownership of prime locations. I expect that this tendency was more or less universal. Kenneth Kidd at Rock Lake in Algonquin Park initiated the first professional archaeology in 1939. This section of the park is part of Haliburton County. Kidd conducted extensive excavations at the main beach area of the park and recovered what might now be considered to be a typical assemblage of materials for the area. At the time Kidd conducted his work there was little material from the area on which to base expectations. It was new ground. His work was not published until 1948, delayed by the Second World War. There wasnt any more archaeology conducted in Haliburton until the 1950s when the reeve of a township in the eastern part of the county discovered a quantity of material that entered the literature as the Farquhar Lake Cache (Popham and Emerson 1954). This cache site contained a quantity of prehistoric copper artifacts in a very tight cluster. The author of this current overview recorded an additional two sites on Farquhar Lake in the 1990s. All sites were revealed as a result of the drop in water levels associated with the fall drawdown of the Trent-Severn Waterways reservoir lakes. In 1957, Paul Sweetman visited a site on an elevation overlooking the narrows of Lake Kashagawigamog. Earth moving equipment being used to prepare a cottage site had inadvertently impacted on a burial site. Further exploration revealed a multi-component site. The most recent material included a bag of French gunflints. The 1960s saw a bit of work performed by Wm. Noble at Rock Lake in Algonquin as well as some by Selwyn Dewdney and K. Kidd who investigated a few pictographs. Wm. Fox has the distinction of being the only archaeologist in the 1960s to work in the area of Haliburton County outside the park bounds when he recorded an important site on Drag Lake, one of the larger lakes at the headwaters of the Burnt River system. During the 1970s the Ministry of Natural Resources became involved in site survey operations and secured the services of Wm. Hurley who conducted survey throughout various sections of Algonquin. He and his crews recorded 21 sites within the Haliburton section of Algonquin Park. Wm. Ross conducted additional surveys in the vicinity of the Leslie Frost Centre property and adjacent areas in Haliburton County recording a total of 16 sites. Thor Conway recorded a site on Gull Lake in the early 1980s.

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________ A major project under the direction of Roberta O'Brien and Annie Gould (Gould 1980) recorded a number of sites in the vicinity of Kawagama Lake. Several larger sites were located at a narrows that provided access to the Algonquin Park interior. A number of private individuals have made contributions over the years. Their collections and research efforts have found their way into the possession of several local museums (Figures 1-3). Staff of the Haliburton Highlands Museum have investigated a number of sites reported by local cottagers and have conducted some survey work on their own. The first archaeological surveys required of developers in Haliburton County weren't conducted until the late 1990s. At that time there were only about 75 registered sites in the whole of Haliburton County -- just the tip of the iceberg. The Physical Environment and Culture In order to enrich our perspective of the archaeology of Haliburton and environs it helps to visualize the geography. I find it helps to think of the Algonquin Dome as a hand with arched and extended fingertips. The back of the hand represents the dome or headwater area and the fingers represent the different drainages and directions they flow. To the west we have the Oxtongue and Hollow Rivers that flow into the Muskoka waterways. The Gull and its tributaries drain the southwestern and central parts of the county, flowing to Balsam Lake. The Drag and Irondale rivers flow into the Burnt that too heads southwest into Cameron Lake. Another minor although important stream is the Black River on the west side. The easternmost portion of the county is drained by the waters of the York Branch of the Madawaska. The lands surrounding Louisa and Pen lakes in the northeast of the county help to fill the waters of the Madawaska. The southeasternmost waters of Haliburton County flow into Eels Creek and south to Stoney Lake, and through the Crowe River into the lower Trent. Although the waters flow downhill to their ultimate destinations, the cultures of the diverse areas tended to evidence themselves by climbing up the waterways. The traditional seasonal routes of many diverse bands of people follow these rivers up into the present-day park. The archaeology of central Haliburton shows evidence of this diversity. The rivers acted like the roots of a tree that fed nourishment to the central location. These water systems either originate in the park, or are but a short portage away. Simply walking over a divide is often enough to connect you to another major stream. Water Levels and their Impact Many of the lakes of Haliburton County are used as reservoirs to moderate and control water levels further to the south along the more populous and heavily used recreational waters. Approximately 30 lakes in the Gull River watershed, another 20 lakes in the Burnt River watershed, as well as Eels Lake on the periphery of the county, are all part of the Trent-Severn system and as a result their levels may fluctuate wildly on a seasonal basis (Figure 1). Additional controls affect the level of waters on the Muskoka, Black, and Crowe rivers, as well as the York Branch of the Madawaska.

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________

Figure 1. The mouth of the Kennisis River is flooded in summer. Some minor drainages have escaped extensive damage from artificial dams, such as that of the Miskwa Ziibi that drains a few small lakes in southern Haliburton County and provided important access into the region for small groups of native hunters who followed the waters north from the Kawarthas. Some small lakes however are heavily impacted by natural factors -- the activities of beaver that can raise their level several metres in extreme cases. There is a small site on Horseshoe Lake in Glamorgan Township that was located on a peninsula when it was discovered. It is now located on an island because of beaver dams. The history of artificial water control finds its origins in the operations of the lumber companies that harvested their respective timber limits beginning in the 1860s. Evidence of timber crib structures can be found along almost any waterway in Haliburton County and vicinity (Figure 2). Prior to giving this brief talk, I thought that I might be well advised to visit a few of the lakes whose water levels dropped in order to allow for the storage of each coming winters meltwaters. I anticipated that it would be important to have some images to better illustrate the extent of what the potential impact might be (Figure 3). Some interesting materials and features were revealed. Many sites along the lakes are represented by waterwashed collections of artifacts which being heavier tend to stay put while the soil matrix which originally surrounded them has been washed away. This is particularly evident in areas with shallow shorelines. A slight elevation of the water level can inundate tremendous amounts of shoreline. Sites are sometimes located on level

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________

Figure 2. Redstone Lake dam with stoplogs removed. The water level is closer to the natural pre-dam level.

Figure 3. A reduction in water levels results in exposed shorelines.

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________

Figure 4. When natural shorelines are revealed at low water, so are archaeological sites and features.

Figure 5. Artifact collection from a submerged site at Raven Lake.

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________ terraces above eroded shorelines. The evidence lying on the exposed sands is a sure giveaway of these locations. The primary impact of fluctuating water levels on many of the lakes and rivers of the area has been the destruction of most shoreline archaeological sites. Many of the recorded sites in the area have been found as a result of examining shorelines during periods of low water levels (Figure 4). The effect can be quite extreme with a remarkable impact on an area with a low shoreline. A one metre decline might result in the emergence of 50 metres of additional shore in extreme cases. The author of this report was contacted by personnel from several ministries in order to have a look at Raven Lake in northern Haliburton County when the dam was being repaired. The water level dropped approximately twelve feet and extensive areas of former shoreline were revealed. In a few hours Craig MacDonald of the Ministry of Natural Resources and the author were able to observe three exposed sites. We had only visited a very small part of the lake. The sites were all water-washed and many artifacts were exposed for the picking (Figure 5). Unfortunately this exposure works equally well for collectors, the curious, and archaeologists alike. Recent investigations by York North Archaeological Services on Kawagama Lake indicate some of the potential impacts that might be encountered. Several small sites were discovered in a relatively shallow bay that led to a portage. The artificially elevated level of Kawagama Lake might be as much as fourteen feet. An observation of sounding operations off the shoreline from the discovered sites indicated that at that depth most of the site had potentially been inundated by the dammed water levels. This has remarkable implications for the interpretation of sites in the vicinity. Observations and Specifics One of the observations of Hurley and Kenyon (1970) was that prehistoric archaeological sites tended to be located or clustered on larger bodies of water, especially those with a common drainage. This indicates a preference for efficient movement and exploitation of a variety of resources. They noted that they did not find too much on smaller or isolated bodies of water. I would like to suggest that there was in fact an exploitation of smaller drainages and water bodies throughout the area that was associated with the period of the fur trade. It became advantageous at that time to follow small streams up through the inevitable succession of beaver dams that characterize these drainages from top to bottom. The sites are small and likely represent very brief stays by small parties but they are there. It is unlikely that any archaeological surveys conducted in the summer are going to be as successful as those conducted later in the year when water levels are reduced to their minimum. I have visited several sites many times over and a few both early and later in the year. Most sites are simply collections of water-washed artifacts. The success rate in finding artifacts is definitely enhanced in the fall when more of the shoreline is exposed.

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________ Sites that are located on sufficiently elevated terraces behind beaches and above rocky shores tend to be the only ones that survive the impact of the water level changes. These sites are of course also sitting on prime recreational and potential cottage locations. In one instance at Esson Lake, a visitor to the museum brought in a small collection of native material and welcomed us to explore his property. He indicated he had recovered the artifacts while erecting his cottage many years ago. Despite an extensive investigation of his shoreline and every reasonably flat spot in the area surrounding his cottage, nothing further was revealed. Since the cottage was on low piers it was possible to lie on ones belly to check for more material beneath the building. The excavation of a small area in this cramped space resulted in the recovery of fragments of a single smashed pot and a quantity of quartz debitage. Several of the more important archaeological sites in Haliburton have come to light as a result of shoreline developments and activities associated with cottaging. Most finds that people bring into the Haliburton Highlands Museum have been made by cottagers mucking about or exploring their properties. For example, the Curtin site was located by a cottager who was excavating a drain. He discovered a few sherds of pottery and brought them into the museum for identification. The author of this report expressed an interest in testing the property to determine the size of the site. It turned out to be quite extensive in terms of a Haliburton archaeological site, whereas most sites tend to be small. A witty colleague has described several of our other discoveries as "arrowhead resharpening stations." But this site was sufficiently extensive to have a midden, and it is the richest site discovered so far in Haliburton County. Our excavations over several years have resulted in the recovery of thousands of artifacts as well as the identification of a number of discrete activity areas. Much of the site remains unexcavated (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The Curtin Site is strategically located on a major chain of lakes.

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________

Figure 7. Vessel rim and shoulder sherds recovered from the midden at the Curtin site. Figure 8. Unusual vessel decoration from the Curtin site, corded body below crossed rim.

Figure 9. Typical smaller vessel from the Curtin site. Figure 10. Linear elements such as this appear on several vessels from the Curtin site. Several of our observations at the Curtin site (Ballantine 1996) are similar to those of other researchers in the area who have consistently noted that the local Algonquian populations were making use of ceramics that appear to be Iroquoian at first glance (Figures 7, 9). There appear to be many similarities in the ceramic material, in fact it seems difficult to assign them to a particular culture. As an exercise I familiarized myself with Ramsden's (1977) methods for analyzing Iroquoian ceramics and conducted a study 9

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________

Figures 11 and 12. Stone bead and drill from the Curtin site. of the ceramics from the Curtin site. The overall results indicated a reasonable association with the Benson site, one of the nearest Iroquoian villages in neighbouring Victoria County. That site has been noted to feature a longhouse for visiting peoples located outside the palisade. A look at some of the images of recovered material from the Curtin site is likely to be familiar to most Iroquoian researchers. There are some vessels however which don't quite fit with expectations -- they just don't match the Iroquoian typology (Figures 8, 10). They may be local or individual variations. For the most part, similarities in the late woodland ceramics exist across central and eastern Ontario. Many of the same motifs occur from Haliburton to Pembroke. It is likely that the most important differences in the cultural materials are to be noted in the lithic artifacts (Figures 11-12). A Few Final Thoughts Although lakeshore cottage development has had a profound impact on archaeological sites in the Haliburton area it is also responsible for most of the archaeological discoveries. The cottages of old likely rested on a few piers or blocks and didn't have a lot of impact. The sites for modern cottages are prepared much differently from those of the bygone era. Extremely large residences resting on completely landscaped lots are frequently the norm. Despite development constraints it is apparent that some cottagers will have their way with the landscape. They may not be building right on the waterfront but they are certainly having a substantial impact. In the past, most archaeological sites were discovered unintentionally or through misadventure when a site was inadvertently unearthed. Concerns for our cultural inheritance and the protection of heritage resources have only started to be addressed in the last few years. The nature of modern development will require us to remain vigilant with respect to our shorelines where so much of our heritage remains to be discovered. I have faith in the individual cottager who finds an artifact from the past. My experience has been that they will eventually bring their finds into the Haliburton Highlands Museum for identification. Most of our collection is derived from that process and we continue to record people's finds in our notes in order to help us tell the story of Haliburton.

10

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________ References. Ballantine, T. 1987 Archaeological Survey on Raven Lake. Archaeological License Report on file with the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Culture. 1996 Second Season Conservation Activities at the Curtin Site, BfGp-4, Ingoldsby, Ontario, 1995. Archaeological License report on file with the Ontario Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Recreation.

Boyle, D. 1891 Lake Weslemkoon. Fourth Annual Report of the Canadian Institute, (Session of 1890-1891.) Being an Appendix to the Report of the Minister of Education, Ontario. Printed by Order of the Legislative Assembly. Toronto. Chamberlain, A. F. 1891 The Algonkian Indians of Baptiste Lake. Fourth Annual Report of the Canadian Institute (Session of 1890-91) Being an Appendix to the Report of the Minister of Education, Ontario. Printed by Order of the Legislative Assembly. Toronto. Gould, A. 1980 The Kawagama Lake (BhGq-1) and Greaves (BhGq-2) Sites Report. South Central Region Conservation Archaeology Report, Ontario Ministry of Culture and Recreation, Toronto, Ontario. W. M. Hurley & I.T. Kenyon 1970 Algonquin Park Archaeology 1970. Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, Research Report No. 3. Kidd, K. E. 1948 A Prehistoric Camp Site at Rock Lake, Algonquin Park, Ontario. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 4: 98-106. Noble, W.C. 1968 Vision Pits, Cairns and Petroglyphs at Rock Lake, Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario. Ontario Archaeology, Vol. 11: 47-64. Popham, R.E. & J.N. Emerson 1954 Manifestations of the Old Copper Industry in Ontario. Pennsylvania Archaeologist, Volume XXIV, No.1. pp. 3-19. Ramsden, P. 1977 A Refinement of Some Aspects of Huron Ceramic Analysis. National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada. Mercury Series. Paper 63.

11

A Brief Survey of the Archaeology of Haliburton County and Vicinity

Tom Ballantine

________________________________________________________________ Reynolds, N. 1968 In Quest of Yesterday. The Provisional County of Haliburton. Minden, Ontario. Ross, W.A. 1975 Leslie M. Frost Natural Resources Centre Archaeological Resource Inventory. Manuscript on file, Ontario Ministry of Culture and Communications, Toronto, Ontario.

12

You might also like

- River Roots and Rabbits - The PlateauDocument24 pagesRiver Roots and Rabbits - The PlateauEliseo Aguilar GarayNo ratings yet

- Algonquin History in The Ottawa River WatershedDocument16 pagesAlgonquin History in The Ottawa River WatershedRussell Diabo100% (2)

- Eureka and Humboldt County: CaliforniaFrom EverandEureka and Humboldt County: CaliforniaRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (5)

- Burke County History and CommunitiesDocument4 pagesBurke County History and Communitiesmad_hatter_No ratings yet

- From Queenston to Kingston: The Hidden Heritage of Lake Ontario's ShorelineFrom EverandFrom Queenston to Kingston: The Hidden Heritage of Lake Ontario's ShorelineRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Salton Sea - California's Overlooked TreasureDocument63 pagesThe Salton Sea - California's Overlooked Treasurefcsidhu3794No ratings yet

- Lake Superior Annotative BibliographiesDocument23 pagesLake Superior Annotative BibliographiesZack KruzinsNo ratings yet

- The Country of the Neutrals (As Far As Comprised in the County of Elgin), From Champlain to TalbotFrom EverandThe Country of the Neutrals (As Far As Comprised in the County of Elgin), From Champlain to TalbotNo ratings yet

- The Country of The Neutrals (As Far As Comprised in The County of Elgin), From Champlain To Talbot by Coyne, James H.Document33 pagesThe Country of The Neutrals (As Far As Comprised in The County of Elgin), From Champlain To Talbot by Coyne, James H.Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Lest We Forget Oregon Gold Ore-Bin Dec 1976Document23 pagesLest We Forget Oregon Gold Ore-Bin Dec 1976A_MacLarenNo ratings yet

- White Lake: A Historical Tour of the Nation's Safest BeachFrom EverandWhite Lake: A Historical Tour of the Nation's Safest BeachNo ratings yet

- Poquosin: A Study of Rural Landscape and SocietyFrom EverandPoquosin: A Study of Rural Landscape and SocietyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Country of the Neutrals (As Far As Comprised in the County of Elgin), From Champlain to TalbotFrom EverandThe Country of the Neutrals (As Far As Comprised in the County of Elgin), From Champlain to TalbotNo ratings yet

- Fish Culture in Yellowstone National Park: The Early Years: 1900-1930From EverandFish Culture in Yellowstone National Park: The Early Years: 1900-1930No ratings yet

- Manteo North Carolina HistoryDocument89 pagesManteo North Carolina HistoryCAP History Library100% (1)

- Notes from a Small Valley A Natural History of Wolli Creek II Vivid and BeautifulFrom EverandNotes from a Small Valley A Natural History of Wolli Creek II Vivid and BeautifulNo ratings yet

- Sand-Trapped History: Uncovering The History of Sleeping Bear Dunes National LakeshoreDocument20 pagesSand-Trapped History: Uncovering The History of Sleeping Bear Dunes National LakeshoreMarie CuratoloNo ratings yet

- Decoding The Toefl Ibt BasicDocument61 pagesDecoding The Toefl Ibt Basiciaan117102No ratings yet

- Hudson River Guide 2015a (Latest)Document104 pagesHudson River Guide 2015a (Latest)Lawrence ZeitlinNo ratings yet

- Hudson River Guide 2012Document54 pagesHudson River Guide 2012Lawrence Zeitlin100% (1)

- 3500YrCulture DraftBDocument19 pages3500YrCulture DraftBMichael Cerulli BillingsleyNo ratings yet

- Fairhaven Ditch: Talk Edit View HistoryDocument3 pagesFairhaven Ditch: Talk Edit View HistorypopularsodaNo ratings yet

- Moe Chem 2014Document1 pageMoe Chem 2014dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Coliform Report June 2014Document1 pageColiform Report June 2014dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- August 2015 ColiformDocument1 pageAugust 2015 ColiformdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- 2014 Invading Species Watch Program Annual ReportDocument34 pages2014 Invading Species Watch Program Annual ReportdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- The Issue of CapacityDocument4 pagesThe Issue of CapacitydudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- About Loon LakeDocument3 pagesAbout Loon LakedudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- MOE Chem 2014Document1 pageMOE Chem 2014dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

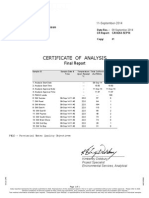

- Report CA14438-SEP12 ExptDocument1 pageReport CA14438-SEP12 ExptdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- 2014 Moe D.ODocument1 page2014 Moe D.OdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Winter Deer Feeding - ConsiderDocument5 pagesWinter Deer Feeding - ConsiderdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Sept 2014 E-Coli TestsDocument1 pageSept 2014 E-Coli TestsdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Report CA16247 AUG12 E ColiDocument1 pageReport CA16247 AUG12 E ColidudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Walleye Watch 2011 Loon LakeDocument4 pagesWalleye Watch 2011 Loon LakedudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- TP ClarityDocument2 pagesTP ClaritydudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- FINALHave You Hugged Your Lake Steward LatelyDocument1 pageFINALHave You Hugged Your Lake Steward LatelydudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- LLPOA Spring 11 NewsletterDocument8 pagesLLPOA Spring 11 NewsletterdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

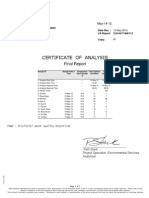

- Report Ca14417-May12 r1Document1 pageReport Ca14417-May12 r1dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- LLPOA - Draft AGM Notes August 2010Document4 pagesLLPOA - Draft AGM Notes August 2010dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Sept 2011 ColiformDocument1 pageSept 2011 ColiformdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Managing Loon Lake's FutureDocument4 pagesManaging Loon Lake's FuturedudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Report Ca14422 Jul10Document1 pageReport Ca14422 Jul10dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Report Ca14422 Jul10Document1 pageReport Ca14422 Jul10dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Water ThreeDocument4 pagesWater ThreedudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Loon-Lake Water Acidic or NotDocument1 pageLoon-Lake Water Acidic or NotdudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Ca14422 Jul10Document4 pagesCa14422 Jul10dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- LOON LAKE WATER TESTING This Is The Second of ThreeDocument5 pagesLOON LAKE WATER TESTING This Is The Second of ThreedudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Report Ca15724 Aug09Document1 pageReport Ca15724 Aug09dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- LOON LAKE WATER TESTING This Is The Second of ThreeDocument5 pagesLOON LAKE WATER TESTING This Is The Second of ThreedudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Ca18592 Jun09Document4 pagesCa18592 Jun09dudmanlakeNo ratings yet

- Frontiers of The Roman Empire PDFDocument205 pagesFrontiers of The Roman Empire PDFCristina Miron100% (1)

- SCIENCE AND ACTIONS FOR SPECIES PROTECTION Noah's Arks For The 21st CenturyDocument271 pagesSCIENCE AND ACTIONS FOR SPECIES PROTECTION Noah's Arks For The 21st CenturyCarlos Andrés Montoya CardonaNo ratings yet

- The Best Things To Do in Binghamton NYDocument5 pagesThe Best Things To Do in Binghamton NYShashank SangwanNo ratings yet

- Epw Articles On Tribal Issues PDFDocument95 pagesEpw Articles On Tribal Issues PDFHarsha VardhanNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Study Guide & Sample Test Questions: Lisa M. Garrett, Director of PersonnelDocument11 pagesReading Comprehension Study Guide & Sample Test Questions: Lisa M. Garrett, Director of PersonnelEstelle Nica Marie DunlaoNo ratings yet

- Getty Show of Morgantina AntiquitiesDocument4 pagesGetty Show of Morgantina AntiquitiesLee Rosenbaum, CultureGrrlNo ratings yet

- Museum Professions - A European Frame of Reference - 2008 - En+frDocument78 pagesMuseum Professions - A European Frame of Reference - 2008 - En+frDan Octavian Paul100% (1)

- Euro 23 Bonn 09Document388 pagesEuro 23 Bonn 09skhaled365049100% (2)

- Portrait Artists - Peale, C.W 2Document189 pagesPortrait Artists - Peale, C.W 2The 18th Century Material Culture Resource CenterNo ratings yet

- BẮC NINH HSG ANH 9 2015 - 2016Document13 pagesBẮC NINH HSG ANH 9 2015 - 2016Phạm Trần Gia HuyNo ratings yet

- Fuss and Sanders - An Aesthetic HeadacheDocument10 pagesFuss and Sanders - An Aesthetic HeadacheMartina SzajowiczNo ratings yet

- The Artist and His Studio: A History of the Creative ProcessDocument2 pagesThe Artist and His Studio: A History of the Creative ProcessFlin Eavan0% (1)

- Sotheby's Nov. 13, 2017, American Art CatalogDocument188 pagesSotheby's Nov. 13, 2017, American Art CatalogTheBerkshireEagle100% (1)

- Rebecca Schneider-Performing Remains (Intro)Document44 pagesRebecca Schneider-Performing Remains (Intro)Mariana LafónNo ratings yet

- 04 01 19 KMOMA SynopsisDocument7 pages04 01 19 KMOMA SynopsisShubham Basak Choudhury100% (1)

- The National Justice MuseumDocument13 pagesThe National Justice Museumapi-501683900No ratings yet

- Informal Learning Context in Teaching ScienceDocument26 pagesInformal Learning Context in Teaching SciencegreesmaNo ratings yet

- Children Visiting MuseumsDocument51 pagesChildren Visiting MuseumsMilena VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Riga 2014Document69 pagesRiga 2014delfistarNo ratings yet

- Pengantar MuseologiDocument8 pagesPengantar Museologiheru2910No ratings yet

- Guiding Is A ProfessionDocument38 pagesGuiding Is A ProfessionGabrielle NavarroNo ratings yet

- Understanding Neolithic Period, Democracy, Cleisthenes and MoreDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Neolithic Period, Democracy, Cleisthenes and MoreYour MaterialsNo ratings yet

- Architecture Portfolio, Asad KhanDocument31 pagesArchitecture Portfolio, Asad KhanAsad KhanNo ratings yet

- U.S. DOD Form outlines Navy museum policyDocument5 pagesU.S. DOD Form outlines Navy museum policydominic bushNo ratings yet

- ROSS - Distinctive Qualities of Net - ArtDocument13 pagesROSS - Distinctive Qualities of Net - ArtPeterGuthrieInativoNo ratings yet

- The Creative DC Action AgendaDocument80 pagesThe Creative DC Action AgendaPeter Corbett100% (2)

- Unit Outline 102085Document17 pagesUnit Outline 102085api-406108641No ratings yet

- Documenting Saribas Malay Art and CultureDocument13 pagesDocumenting Saribas Malay Art and Cultureharras lordNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Survey PDFDocument11 pagesDescriptive Survey PDFALFIE DILAGNo ratings yet

- Casa GorordoDocument2 pagesCasa Gorordomia_avila_3No ratings yet