Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acute Appendicytis

Uploaded by

Methew BrianOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute Appendicytis

Uploaded by

Methew BrianCopyright:

Available Formats

1

LECTURE ACUTE APPENDICITIS

Acute appendicitis till now is one of the most important surgical problems. It's enough to say, that appendectomy constitutes about 20 -30% of all surgery. In Ukraine about 500.000 appendectomies are performed annually without marked downtrend (A.A. Shalimov, 1989). Studies of appendix had passed many stages before the modern system of etiology, pathogenesis, clinical picture and treatment was created. This disease is insidious one. The existent conception about it as about of slight indisposition is easily disproved by statistics. Lethality seems to be not high, taking into consideration the incidence of the disease; it is rarely exceeds 0,2-0,3%, but these figures mean dozens of thousands lives. The first appendectomies had been performed by Kronlein in 1883, by Malomed in 1884, and by A.A. Troyanov in 1890. Brief Anatomo-Topographic Sketch Vermiform appendix (appendix vermiformis) is the constituent of the iliocaecal angle, which presents morphological integrity of four intestinal departments: the caecum, terminal end of the ileum, initial part of the ascending colon, and the vermiform process. All the constituents of the iliocaecal angle are in strict correlation and perform the function of "internal analyzer", coordinating the most important function of the intestine conduction of chyme from the small to large intestine (A.M. Maximenkov, 1972). The important element of iliocaecal angle is the iliocaecal (Bauhin's) valve (valva ileocaecalis) with very intricate structure. Its function is to accomplish regulation in transition of intestinal content to the caecum in little portions and to prevent its return from the caecum to the small intestine. The iliocaecal angle is situated in the right ileac fossa. Fundus of the caecum is projected on the distance of 4-5 cm upwards the center of the inguinal ligament; under condition of its filling, fundus of caecum is located just above the center of the inguinal ligament or may even descend to the small pelvis. Great variability in anatomotopographic situation of the caecum and the vermiform process explains in many respects such a diversity of clinical picture, which may be observed in acute appendicitis.

The most frequent and practically important deviations from the normal position of the caecum are the following (V. I. Kolesov,1959): 1) 2) high, or hepatic position, when the caecum and the vermiform process are low, or pelvic position, when the caecum and the vermiform process are situated Other variants of it localization, such as its left-side position, location along the middle line of the abdomen, in the umbilical region, in the left hypochondrium, in the hernial sac, etc. occur rather infrequently. The vermiform process is located intraperitoneally. It has its own mesentery (mesenteriolum), which supplies it with vessels and nerves. Blood supply of the iliocaecal angel is provided owing to the superior mesenteric artery a. ileocolica, which is subdivided into the anterior and posterior iliac arteries. The natural artery of vermiform process a. appendicularis, which may have a loose, arterial or mixed structure, branches off from a. ileocolica or from its branch. Artery of the vermiform process goes through its mesenteries, along its free edge, to the end of the process. Though its small caliber (from 1 to 3 mm), post-operative hemorrhages from a. appendicularis may be very intensive, as a rule, they require relaparotomy. Veins of the caecum and the vermiform process are the tributaries of the ileocolic vein (v. ileocolica), which flows in the superior mesenteric vein (v. mesenterica superior). Innervation of the iliocaecal angle is performed by the superior mesenteric plexus, which is connected with the celiac (solar) plexus, which takes part in innervation of all digestive organs. The iliocaecal angle is considered to be "the junction depot" of all abdominal organs innervation. Running from here impulses influence functions of many organs. The peculiarity of innervation of the iliocaecal angle and the vermiform process explains the onset of pain in the epigastrium and their spreading over the abdomen in acute appendicitis. Lymph outflow from the vermiform process and from the iliocaecal angle performs entirely to the lymphatic vessels, which are situated along the ileocolic artery. There is a situated high, sometimes reaching the lower border of the liver; below normal, i.e. descends to the pelvis.

chain of lymph nodes (10-20) along this artery, which extends to the central group of mesenteric lymph nodes. Immediate proximity of the mesenteric and iliac lymph nodes explains the similarity of clinical picture in inflammation of these nodes (acute mesenteric adenitis) and in inflammation of the vermiform process. Five variants of localization of the vermiform process with respect to the caecum are distinguished: descending (caudal (is); lateral, internal (medial), anterior (ventral), and posterior (retrocaecal). In descending, more frequent localization, the vermiform process, directing towards the small pelvis, adjoins to certain extent the organs of the small pelvis. In lateral position, the process lies from the outside of the caecum. Its apex is directed to the inguinal (Poupart's) ligament. Medial localization is also rather frequent. In those cases the vermiform process lays medially to the caecum, being localized between the loops of the small intestine; all these provide favorable conditions for extent inflammation inside the abdominal cavity and give rise to abscesses. The anterior position of the process, in which it lies in front of the caecum, occurs rarely. Such localization is favorable to anterior parietal abscess. Some of the surgeons mark out ascending type of the process localization. Here, the two variants are possible. The first one, in which the whole iliocaecal angle is located rather high, under the liver, and then the term subhepatic position of the vermiform process is applied, or the second variant, when the apex of the retrocaecal vermiform process is directed to ward the liver. Retrocaecal position of the process, which is observed in 2-5% of the patients, two variants of its bedding with respect to the peritoneum is characteristic: in some cases the process, being covered with the peritoneum, lies in the iliac fossa behind the caecum, while in other cases it projects from the leaf of the peritoneum and lies intraperitoneally. This position of the vermiform process is termed retrocaecal (retroperitoneal) one. The latter is considered to be the most insidious variant, especially in suppurative and destructive appendicitis, since in the absence of the peritoneal cover of the process the inflammatory process extends to the paraumbilical fat, causing deep retroperitoneal phlegmon.

Etiology, Pathogenesis, Pathologic Anatomy, and Classification There is no consensus of opinion about etiology of acute appendicitis. But there are some theories explaining the causes of the disease and its pathogenesis. The most common of them is mechanical (congestion), infectious, and aponeurotic theories. Besides that, at different periods a number of conceptions, sometimes very original, were elaborated. All the theories and conceptions, reflecting one or another etiological agent are not without logic and sense. At the same time, a variety of forms and stages of acute appendicitis suggests the polyetiology of this disease, which results from the changed correlation between the human body and microorganisms. It being known, acute appendicitis is a non-specific inflammation of the vermiform process. The causative agents of infections may be staphylococci, colon bacilli, and mixed and anaerobic flora. All the efforts on choosing a particular pathogenic organism and to number acute appendicitis among specific inflammatory disease were not successful. Mechanical theory indicates the role of foreign bodies, infections and scary strictures of the vermiform process in development of acute appendicitis. But these factors occur are far from being in all the patients. Helmint invasion and angina (sore throat) are of great, but not absolute importance in genesis of the disease. Infectious theory correctly indicates the role of infection and the primary affect, but does not explain what stimulates an infection, which is permanently present in the lumen of the vermiform process. And similar weak points take place among the other theories and conceptions. Gained scientific and practical experience proves that taking into consideration the variety of clinical and morphological forms of the disease, there may be several predisposing factors and their combinations. For example, the following mechanisms and ways of development of acute appendicitis are quite logical: 1. Obstruction of the lumen of the process and formation of a closed cavity filled with feces, which contain toxins with highly reactive enzymes, gradually result in suppuration, lesion of the mucous membrane, and infection penetrates inside the vermiform process wall. Development of exudative inflammation is accompanied by microcirculatory disturbances and degeneration of intramural neural apparatus. But neurodystrophic changes together with the vascular factor constantly result in

inflammatory intensification and its progressing up to formation of phlegmon or gangrene. 2. Due to neurological disturbances, vascular stasis occurs in the vermiform process. It results in trophopathy of the vermiform process and formation of necrotic foci. Pathologically changed tissues are easily infected, i.e. secondary infection takes place. The following spread of the infectious process causes more extensive pathologic changes with all possible severe consequences. 3. Primary formation of acute ulceration in the vermiform process, which had been observed by Selye at general adaptation syndrome, is possible. It may be the result of neurogenic vasospasm. 4. In those cases, when abrupt clinical picture of the disease is followed very rapidly by gangrene of the vermiform process, it is quite possible to consider primary thrombosis of a. appendicularis and its branches. Inflammatory component and infection join secondarily. Appendicular colic. It means a muscle spasm of the vermiform process, caused by any of pathologic process and proved by pain in the right iliac area. A surgeon makes this diagnosis in those cases, when clinical manifestations disappear quickly, or when at the time of operation he does not see any inflammatory changes in the vermiform process. Catarrhal (congestive) appendicitis. Exudate may be absent or it may be in very small amount. It is transparent, odorless. The peritoneum is unchanged and is hyperemic a little. All changes are strictly localized in the vermiform process. It is hyperemic along the whole length or at the limited site (usually distal one), thick to the touch, slightly edematous. The lumen of the process may be either empty, or may contain mucus, impacted feces, and foreign bodies. The mesentery is not changed, or may be slightly edematous and hyperemic one. Microscopically: leukocyte infiltrations in the impaired sites of the process. Sometimes it is possible to find out a defect of the mucous membrane (primary affect), which is covered with fibrin and cellular elements. Phlegmonous appendicitis. Exudate may be serous, serofibrous, seropurulent one. Fetid odor appears at perforation of the vermiform appendix. In most of cases it is possible to speak about the local peritonitis, but in advanced cases, when the process is

not delimited, but the amount of exudates is considerable and it baths the large sites of the abdominal cavity, it is possible to consider diffuse and even general peritonitis. The omentum, the caecum, and adjacent loops of the small intestine may be also involved in the pathologic process. They are hyperemic, thickened, are covered with fibropurulent deposit and are fused by loose adhesions. The vermiform appendix is considerably enlarged in its sizes, is of dark red color, strained is covered with mucous fibrin. The sites of white-yellowish pus may be often seen through the transparent serous coat. Pus, which is inside the lumen of the organ, is gradually stretching it, and empyema is formed. The mesentery is thickened, its leaves are hyperemic and edematous, may be easily treated. Similar changes are frequently observed in the caecum cupola wall and considerably complicate appendectomy. On microscopic examination it is possible to reveal leukocyte infiltration of all the layers of the vermiform process; it is impossible to differentiate them due to their saturation with pus. Apostematous appendicitis takes place in case of appearance of multiple abscesses against a background of diffuse purulent inflammation of appendix. In case of ulceration of the mucous membrane against a background of phlegmonous appendicitis, phlegmonous-ulcerative appendicitis occurs. Gangrenous appendicitis. Abdominal changes are similar to phlegmonous appendicitis, but they are more pronounced. Exudate is turbid, with ichorous purulent odor. The vermiform process is partly or completely of black, brown, brown-green, black-brown, or dirty-gray color. Its wall is flabby with phlegmonous masses. Gangrenous appendicitis is frequently perforating one, and then it is possible to see fetid feces pouring through the opening in its wall inside the abdominal cavity. As a rule, peritonitis occurs. It may be local, diffuse, or general, but according to the nature of microflora, colibacillary, anaerobic, and mixed types are distinguished. Extensive necrotic foci with bacteria colonies, hemorrhages, and vascular thrombosis may be revealed on microscopic investigation. Somewhere it is possible to see the foci of phlegmonous inflammation. The mucous membrane is ulcerated all along. As a rule, destructive changes are pronounced up to perforation in the distal part of the organ. Generalization of infection in a form of endotoxic shock occur in gangrenous appendicitis more frequently than in other forms of inflammation.

Appendicular infiltrate is one of the complications of acute appendicitis. The vermiform appendix, being destructively changed, becomes an epicenter of adhesion process. A conglomerate of chaotically fused neighboring organs and tissues is formed around it. The greater omentum, loops of the small intestine, the caecum and ascending intestine, the peritoneum become involved in the pathologic process. The wall of these organs are subjected to inflammatory infiltration, the boundaries between them become gradually lost. Infiltrate rapidly increases in sizes, being compactly connected to the anterior, posterior, and lateral walls of the abdomen. Sometimes infiltrate is of vast sizes, occupying the whole right side of the abdomen. Classification But there are two classifications, which are used by the present and make it easier to choose the policy of treatment. They are the classification according to A.I. Abrikosov (1946), in which he wanted to reflect the problems of acute appendicitis pathologic anatomy, and the classification according to V.I. Kolesov (1959), where he tried to reflect clinical forms of acute appendicitis and its complications. Classification according to A.I. Abrikosov: I Superficial appendicitis (primary affect); II Phlegmonous appendicitis: 1)

2)

simple phlegmonous appendicitis; ulcer phlegmonous appendicitis; apostematous appendicitis; with perforation; without perforation; empyema of the vermiform appendix;

3) a) b) c)

III Gangrenous appendicitis: 1)primary gangrenous appendicitis; a) b) with perforation; without perforation;

2) secondary gangrenous appendicitis:

a) b)

with perforation; without perforation.

Classification according to V.I. Kolesov: I. Acute simple (superficial) appendicitis; A) Without general clinical signs, but with mild local, quickly disappearing, manifestations of the disease. B) With insignificant general clinical signs and local manifestations of the disease. II. Destructive acute appendicitis (phlegmonous, gangrenous, perforating): A) With clinical picture of moderate severity and the signs of local peritonitis; B) With severe clinical picture and the signs of local peritonitis; III. Complicated appendicitis: A) With appendicular infiltrate;

B)

With appendicular abscess;

C) With diffuse peritonitis. The Main Principles of Medical Aid in Acute Appendices 1) On suspicion of acute appendicitis the patient is subjected to urgent hospitalization to the surgical unit, he is to be under constant medical care and to undergo additional examination. 2) Recognized acute appendicitis requires an urgent surgical invention, irrespective to manifestation of clinical picture, the age of a patient, duration of the disease (with the exception of delimited infiltrates). 3) In vague cases, in the presence of suspicion of acute appendicitis, it is necessary to perform laparoscopy or explorative laparotomy. 4) In the absence of changes in the vermiform appendix during the operation, or in case of not corresponding of revealed changes with clinical picture, it is necessary to perform revision of the abdominal cavity.

Clinical Picture, Diagnostics, and Treatment Acute appendicitis is characterized by variety of clinical manifestations. I.I. Grekov figuratively called it "a chameleon-like disease", and Y.Y. Dzhanelidze called it as insidious one. Almost all the symptoms of acute appendicitis are non-specific, i.e. occur in many other abdominal diseases. That is why the symptom is not important by itself, but its characteristics, combination with other symptoms and the consequence of its appearance are very important in diagnostics. One and the same symptom at different stages of the disease and at different forms of it has its own features. There are three main forms of acute appendicitis: 1) early stage (up to 12 hours); 2) stage of development of destructive changes in the vermiform appendix (from 12 to 48 hours); 3) stage of complications (48 hours and more). This division at stages is rather relative one, and the disease may run by its own, much more transient scenario, however, more frequently it proceeds exactly in such a way. Pain is the first and most common symptom of acute appendicitis. It occurs predominantly at night, becomes constant, gradually intensifying. Patients may characterize pain as piercing, cutting, burning, dull, acute one. At the first stage of the disease the intensity of pain is not significant, it is quite tolerable. Patients do not cry or moan, but also do not show superfluous motive activity, as jerky movements of the body, for example, at cough (the cough shock symptom) intensify the pain. Cramping pain occur very rarely. Localization of pain is different. In typical cases it is localized at once in the right iliac area, but it also may not be localized, but spreading all over the abdomen. Approximately in a half of patients it locates at first it the epigastric area (Kocher Volkovich's sign), and only in 1-2 hours descends to the right iliac area. Sometimes this symptom lasts for more prolonged time, and it considerably hampers differential diagnosis. At the second stage of the disease, on developing of destructive changes in the vermiform process, pain increases, causing the patients to suffer. The most severe pain is in empyema, when pressure increases in the lumen of the vermiform process. In those cases the patients rush about, they could not find a place for themselves. On the background of constant pain a patient suddenly feels the increase of pain perforating

10

symptom. But paradoxical reaction is rather frequent too, when during the process of destruction pains subside up to their complete disappearance; this is associated with gangrene of the vermiform appendix wall. Discrepancy of severe condition of the patient and clinical picture is evident. At the third stage clinical picture of either appendicular infiltrate or abscess or peritonitis is revealed. Pain may radiate to different parts of the abdomen: to the umbilicus, to the epigastric area, and to the loin. It depends on position of the caecum and the vermiform process. Nausea and vomiting is observed in 60 -80% of patients (V.I. Kolesov, 1972). Nausea usually precedes vomiting, but sometimes it may be an independent symptom. It is important that these symptoms do not ever precede pains, but arises during the first or the second hour of the disease. At the first stage vomiting is of reflex nature, with mucous and eaten food. At the second and third stages vomiting occurs again, but now its frequency and nature depend predominantly upon expressiveness of peritonitis, intoxication and developing dynamic (paralytic) intestinal insufficiency. Gas and stools retention. They are immutable concomitants of acute appendicitis. At the first stage of the disease retention of gas and stools occurs as physiologic, reflex reaction to outside stimulants, but later it results from paralytic ileus in peritonitis. Loose stools is rather infrequent, it may be observed mainly in children in case of spreading of inflammatory process on the sigmoid colon or the large intestine. In case of pelvic location of the vermiform appendix and its contiguity with the urinary bladder wall disuric disturbances are possible. At the onset of the disease temperature averages 37-38C. Pulse rate corresponds to the temperature-80 -100 beats per minute. Only in destructive forms of appendicitis temperature may be 38,5-39C, but tachycardia becomes 130 -140 beats per minute. Thermometer readings under the armpit and into the rectum are to be compared because of certain diagnostic importance. Revealing of considerable difference (over 1/5C) objectively testifies an acute pathology in the abdomen. Examination of the abdomen. At an onset of the disease the abdomen usually of normal form, moves with breathing, symmetrical. In lean patients it is possible to notice

11

the lag of the right side of the abdomen in respiratory movements due to muscular strain (Ivanov's symptom). In perforating of the vermiform appendix the respiratory movements of the anterior abdominal wall disappear. In a man of athletic type it is possible to notice the relief of strained abdominal muscles. Abdominal distention is the late symptom. It testifies the development of peritonitis. Muscular tension (defanse musculare) is the main symptom in acute appendicitis. In severe cases the site of the most tenderness and local tension of the abdominal wall is in the right iliac area; the degree of the muscular tension increases in accordance with intensity of the inflammatory process inside the peritoneum. Revealing of the symptom requires a certain experience. Infrequently the patient strains the abdominal wall by himself, preventing the pain, especially if the investigation is carried out unskillfully and crudely. At the first stage of the disease the muscular tension may be absent. It may be frequently observed in elder and senile persons and in women with flabby and dilated abdominal wall, who had experienced labors many times, and also at retrocaecal, retroperitoneal and pelvic localization of the vermiform appendix. Deep palpation of the most painful area is not expedient. It rarely gives additional information, as it is usually prevented by muscular protection. But at soft abdomen deep palpation allows to diagnose appendicular infiltrate, to determine its size and bounds, consistency, mobility. Sometimes it is possible to feel the caecum, area of which is always painful in case of acute appendicitis. But it is almost impossible to feel the vermiform appendix, and it is not necessary. Revealing of painful points (McBurney's point, points of Lanz and Kummel) is not of great diagnostic value. In acute appendicitis tenderness of the abdomen is rarely strictly localized. Blumberg's sign (guarding symptom) is a rebound tenderness symptom. Already at the early stage of acute appendicitis, at mild catarrhal inflammation of the parietal peritoneum it is usually positive. The following may check it. The tips of the fingers are introduced very gently and gradually into the anterior abdominal wall, pressing it inside the abdomen. Then the arm is abruptly taken away. In positive reaction the patient notes the increase of pain, sometimes he shrivels and utters a scream. Percussion of the abdomen allows to localize the area of the greatest tenderness

12

more precisely (Razdolsky's (abductor of femur sign). These are also rebound tenderness symptoms. A slight percussion of the abdominal wall at its different sites is enough to determine this symptom. By means of percussion, being oriented on the dullness of the percussion sound it is easy to estimate the bounds of appendicular infiltrate, and in peritonitis the presence of fluid in sloping places of the abdomen. Auscultation of the abdomen allows to estimate the intestinal peristalsis. Already at an early stage of the disease it is weakened, but survives for a long time. The absence of peristalsis is a threatening symptom of peritonitis. Appendicular symptoms. More than 100 symptoms of appendicitis had been already described. We shall settle on only on some of them, which are the most pathognomonic, and gained popularity among the surgeons. Sitkovsky's sign. A patient is asked to turn on his left side. If at that the pain in the right iliac region arises, the symptom will be considered to be positive one. Bartomye's symptom is checked as Sitkovsky's one, but at the same time palpation of the right iliac region is performed. At positive symptom palpatory tenderness increases. Rovsing's symptom. In dorsal position of a patient, a surgeon presses the sigmoid colon to the posterior abdominal wall with the fingertips of the left arm and fixes it. Simultaneously, a little above, by means of balloting palpation, he shakes the abdominal wall in the sigmoid area. The onset of pain in the right half of the abdomen is the evidence of a positive symptom. Voskresensky's symptom. A shirt or T-shirt of a patient is tightened with the left arm and fixed at the pubis. By fingertips of the right arm a surgeon slightly presses to the abdominal wall in the area of the xiphisternum, and at time of expiration performs a quick uniform sliding motion at first towards the left iliac-inguinal region, and then to the right one, but for all that the arm is held on the abdominal wall. In the presence of positive symptom a patient feels pain in the right side. It is also necessary to remember some other appendicular symptoms, such as Corn's, Britten's, Chugaev's, Cope's, Dumbadze's, Rizvash's, Gabay's, Yaure-Rozanov's, Punin's, Bulynin's, and Promptov's symptoms.

13

Laboratory Diagnosis Moderate leukocytosis is noted at an early stage of the disease. In catarrhal form of inflammation it is from 10xl09/l to 12xl09 /I, in destructive forms it achieves 14xl09/l18xl09/l, but sometimes it may be even higher, It is dangerous when neutrophilic shift of differential blood count to the left takes place. The increase of stab neutrophil up to 1016% and appearance of juvenile forms is the evidence of high degree intoxication. Laboratory investigations of the blood may be widened by examination of Creactive blood protein (C-RP), phagocyte activity of neutrophils, investigation of alkaline phosphatase, peroxides, oxidase, and cytochrome oxidase. However, non-specific character and considerable labor-consuming nature of these reactions decreases their diagnostic value in urgent surgery. Urinary tests reveal pathologic changes in severe intoxication and peritonitis. In uncertain diagnosis of acute appendicitis, laparoscopy is of particular value; approximately in 90% of cases it puts an end to doubt in diagnosis. Especially often the necessity of laparoscopy occurs at differential diagnosis with genital diseases and renal colic. Complications in Acute Appendicitis Appendicular infiltrate occurs in 0.9-2.9% of patients, who had been hospitalized in 48 hours and later from the onset of the disease with evident prevalence of elder and senile patients. Morphologic and clinical essence of infiltrate consists in the inflammatory focus in the vermiform appendix is delimited from the free abdomen by the omentum, and the adjacent tissues and organs, which are also involved in the inflammatory process, united into one conglomerate, which is connected with the anterior, posterior or lateral abdominal wall. The size of infiltrate may be different, from small one, with the size of a fist, to the giant one, occupying the whole right side of the abdomen. The boundaries of infiltrate, as a rule, are distinct; their mobility is usually limited. As a whole, it takes about 2-5 days to form appendicular infiltrate; during this

14

period it passes several stages (A.I. Krakovsky and co-authors, 1986): 1 . Loose infiltrate. In typical cases it is located in front of the caecum, with mild peritoneal response, purulent exudate in the small pelvis, with involvement of the caecum, phlegmonous or gangrenous appendicitis, omentum, and the loops of the small intestine; 2. Dense infiltrate, which can be either resolved or form an abscess; 3. Periappendicular abscess. Infrequently diagnosis is difficult. Before surgery it is possible to make a correct diagnosis only in a half of patients. Sometimes there are quite forcible arguments, foe example, atypical position of the vermiform appendix and, accordingly, of infiltrate in the small pelvis or behind the caecum; excessive obesity of patients with abundant layer of fatty tissue; impossibility of deep palpation due to acute tenderness and protective muscular tension. Insufficiently careful and full-value investigation is the common reason of diagnostic pitfall. In typical cases the delimitation of the process in phlegmonous appendicitis without any signs of perforation must coincide with gradual improvement of the patient's general condition and control of acute manifestations. The pains gradually cease up to their complete disappearance. Pulse becomes normal. Temperature decreases, but, however, remains stably sub febrile. Signs of dynamic intestinal obstruction disappear rapidly. Subsequent course of the disease may be different. Three variants are possible. The most favorable one is resorbtion under the influence of conservative treatment. Usually it takes approximately from 2 weeks to 1 month. The second variant is the most dangerous of all, when peritonitis progresses simultaneously with the process of infiltrate formation. And, finally, the third variant infiltrate abscess formation, when in the presence of obviously localized process, clinical manifestations of purulent septic process are evident: increase of pain in the infiltrate area, hectic fever with chills, and intoxication. General Appendicular Peritonitis Difficulties and dangers of acute appendicitis at common appendicular peritonitis

15

reach the apogee. Incidence of this complication averages from 0,6 to 4,1%. It is necessary to note, that among the causes of common peritonitis acute appendicitis takes the first position, achieving 50-55% (A.A. Shalimov, 1990). Clinical picture, diagnosis and treatment of common peritonitis are expounded in the appropriate lecture. Pilephlebitis Purulent trombophlebitis in the region of the superior mesenteric or portal vein is one of the most severe complications of acute appendicitis. It occurs rather seldom, in 0,06-1,5% of cases from general number of patients with this disease. The course of the disease is exclusively severe; with fatal outcome in most cases. In 1986 V.S. Savelyev advanced the opinion that there were no reliable observations of pilephlebitis. Information of N.V. Karamanov about successful treatment of 11 patients with pilephlebitis seems to be more optimistic. Timeliness diagnostics is a guarantee of success. Appearance on the background acute appendicitis clinical picture such symptoms as chill, hectic fever, pain in the right hypochondrium, jaundice, etc., including laboratory data, proving severe intoxication, must put a surgeon on his guard. Treatment of Acute Appendicitis Treatment is only operative; there is no choice. Delay of operation is dangerous by impetuous course of the process and development of the severest complications. The only contraindication for operation is the presence of dense appendicular infiltrate but only in those cases when there is no signs of abscess formation and peritonitis. Being dependable on clinical situation, the operation may be performed both under local and general anesthesia. General anesthesia is preferable. Three main approaches to the vermiform appendix are used: oblique (Volkovich-Dyakonov's), Lenander's (pararectal) incisions, and midline laparotomy. In all cases of acute appendicitis with strictly localized clinical picture in the right iliac fossa an oblique incision is applied. At typical position of the caecum and in other positions of the vermiform appendix, optimal conditions are produced due to this incision. Pararectal Lenander's incision is applied in case of vague diagnosis. It may be

16

rapidly elongated up and downwards. But in case of retrocaecal position of the appendix and at local periappendicular abscesses Leanders incision is not so suitable. Mid-midline or low-midline laparotomy is applied in the presence of clinical signs of diffuse and general peritonitis. Operation technique for appendectomy is identical on principle in various forms of inflammation of the vermiform appendix, but each of them introduces its own features and a number of additional tricks in performance of operation. In catarrhal appendicitis before performance of operation it is necessary to make certain that visible morphological changes correspond to clinical picture of the disease and are not the secondary ones. In phlegmonous appendicitis, having evacuated the exudates from the right iliac fossa, it is necessary to determine that the process inside the abdomen is localized; for this purpose the surgeon examines the right lateral canal, right mesenteric sinus and cavity of the small pelvis by means of a swab. If muddy exudate appears from these spaces of the lower abdomen, it is necessary to suggest diffuse or general peritonitis. At the beginning of operation for appendectomy of gangrenous appendix it is necessary to delimit carefully the area of the iliocaecal angle from the other portions of the abdominal cavity by means of wide gauze towels. In case of perforation, one should thoroughly wrap the vermiform appendix with wet towel, avoiding the appearance of intestinal content inside the abdominal cavity. Operation in conditions of appendicular infiltrate is fraught with many dangers. In such a case it is necessary to exhibit a particular wisdom. It is on these conditions that excessive activity of the surgeon may result in a number of serious complications and in the growth of lethality (diffuse peritonitis, sepsis, intestinal fistula, thromboembolism, bleedings). Retrograde appendectomy is performed in those cases, when it becomes impossible to draw out both the caecum and appendix into the wound due to adhesions and inflammatory infiltration. Ligation of the mesentery applying a purse-string suture and treatment of the appendicle stump are the most important stages of appendectomy. It is prohibited to be in hurry. Everything must be done carefully and safely. It is these stages of operation that may result in such complications as postoperative abdominal hemorrhages, postoperative

17

peritonitis, intestinal fistula, abdominal abscess, etc. This is the end of our lecture for problem of acute appendicitis. Many particular problems of this surgical disease were mentioned only in passing, and some of them did not touched at all. An interested reader will find answers on his questions in recommended special literature.

You might also like

- Water QualityDocument34 pagesWater QualitySarim ChNo ratings yet

- Compliance Program Guidance Manual 7341.002 PDFDocument45 pagesCompliance Program Guidance Manual 7341.002 PDFpopatlilo2No ratings yet

- Understanding the Anatomy and Physiology of AppendicitisDocument39 pagesUnderstanding the Anatomy and Physiology of AppendicitisArmitha DhewiNo ratings yet

- Filaria PPT - ClassDocument59 pagesFilaria PPT - ClassGauravMeratwal100% (2)

- Pediatric Radiology ShortDocument95 pagesPediatric Radiology ShortNelly ChinelliNo ratings yet

- 220 Nursing Fundamentals Review BulletsDocument40 pages220 Nursing Fundamentals Review Bulletsjosephmary09No ratings yet

- Scabies and PediculosisDocument35 pagesScabies and PediculosisleenaloveuNo ratings yet

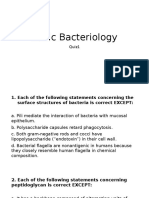

- Microbiology Quiz1 (Basic Bacteriology)Document26 pagesMicrobiology Quiz1 (Basic Bacteriology)ROHITNo ratings yet

- CH 22 Lymphatics F 2017Document143 pagesCH 22 Lymphatics F 2017JuliaNo ratings yet

- Appendicits Case Study LATEST CHANGESDocument25 pagesAppendicits Case Study LATEST CHANGESJesse James Advincula Edjec100% (12)

- Control of Insects and RodentsDocument21 pagesControl of Insects and RodentsZam PamateNo ratings yet

- IntussusceptionDocument10 pagesIntussusceptionhya2284No ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal PerforationDocument33 pagesGastrointestinal PerforationGuan-Ying WuNo ratings yet

- 7 SemesterDocument68 pages7 SemesterbelizrivadeNo ratings yet

- Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of AppendicitisDocument15 pagesCauses, Symptoms, and Treatment of AppendicitisnikkitaihsanNo ratings yet

- Journal AslinyaDocument11 pagesJournal AslinyainNo ratings yet

- Appendix Part 1Document8 pagesAppendix Part 1Abdullah EssaNo ratings yet

- Lection 6. Acute PeritonitisDocument12 pagesLection 6. Acute PeritonitisOussama ANo ratings yet

- Jejunal and Ileal AtresiasDocument37 pagesJejunal and Ileal AtresiasABDUL RAHIM UMAR FAROUKNo ratings yet

- Acute PeritonitisDocument11 pagesAcute Peritonitisangelmd83100% (1)

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults - Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument9 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults - Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis - UpToDateSebastian CamachoNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults - Clinical Manifestations and Differential DiagnosisDocument17 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults - Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosisnicholas Rojas SIlvaNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults: Clinical Manifestations and DiagnosisDocument37 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults: Clinical Manifestations and DiagnosisDaniela MuñozNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults Clinical Ma PDFDocument27 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults Clinical Ma PDFAntonio Zumaque CarrascalNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis: Dr. Aplin I, SPBDocument12 pagesAppendicitis: Dr. Aplin I, SPBAyu Kusuma NingrumNo ratings yet

- Acute appendicitis symptoms and causesDocument20 pagesAcute appendicitis symptoms and causesAiyaz AliNo ratings yet

- Sabitson - Appendiks EngDocument17 pagesSabitson - Appendiks Engzeek powerNo ratings yet

- MDSCPDocument12 pagesMDSCParranyNo ratings yet

- The Anatomy and Development of the Vermiform AppendixDocument10 pagesThe Anatomy and Development of the Vermiform AppendixBereket temesgenNo ratings yet

- Vermiform AppendixDocument4 pagesVermiform AppendixHarun NasutionNo ratings yet

- Apendicitis Aguda1Document4 pagesApendicitis Aguda1Montserrat CandiaNo ratings yet

- Peritonitis EmedscapeDocument38 pagesPeritonitis EmedscapeNisrina FarihaNo ratings yet

- PeritonitisDocument122 pagesPeritonitisSub 7 Grp 3No ratings yet

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Appendix: Publication DetailsDocument5 pagesAnatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Appendix: Publication DetailsAndiNo ratings yet

- Acute AppendicitisDocument9 pagesAcute AppendicitisSyarafina AzmanNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Perforation: BackgroundDocument5 pagesIntestinal Perforation: BackgroundpricillyaNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis Method EngDocument10 pagesAppendicitis Method EngMohammad AyoubNo ratings yet

- Peritonitis and Abdominal Sepsis: Background, Anatomy, PathophysiologyDocument16 pagesPeritonitis and Abdominal Sepsis: Background, Anatomy, PathophysiologyTias SubagioNo ratings yet

- Peritonitis and Abdominal Sepsis Background, Anatomy, PathophysiologyDocument1 pagePeritonitis and Abdominal Sepsis Background, Anatomy, PathophysiologyFlora Eka HeinzendorfNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults: Clinical Manifestations and Differential DiagnosisDocument35 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults: Clinical Manifestations and Differential DiagnosissebasNo ratings yet

- Peritonitis and Abdominal SepsisDocument37 pagesPeritonitis and Abdominal SepsisFernando AsencioNo ratings yet

- 2 Semester 1 Major Patho AnatoDocument49 pages2 Semester 1 Major Patho AnatoManushi HenadeeraNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults 202302Document13 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults 202302laura correaNo ratings yet

- Review Articles: Acute AppendicitisDocument10 pagesReview Articles: Acute AppendicitisRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Surgical Diseases of PancreasDocument17 pagesSurgical Diseases of PancreasIris BakerNo ratings yet

- Small Nowel Emergency SurgeryDocument8 pagesSmall Nowel Emergency SurgerySurya Nirmala DewiNo ratings yet

- The Pathophysiology of Peritonitis: Review ArticleDocument20 pagesThe Pathophysiology of Peritonitis: Review ArticlepogichannyNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis - PeritonitisDocument37 pagesAppendicitis - PeritonitisanisamayaNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument46 pagesAcute Appendicitis: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentRAJAT DUGGALNo ratings yet

- EsophagusDocument168 pagesEsophagusnancy voraNo ratings yet

- Tarlac State UniversityDocument11 pagesTarlac State UniversityJenica DancilNo ratings yet

- Capitol University College of Nursing: Acute AppendicitisDocument28 pagesCapitol University College of Nursing: Acute AppendicitisCatherine Milar DescallarNo ratings yet

- Overview of Gastrointestinal Tract PerforationDocument37 pagesOverview of Gastrointestinal Tract PerforationArbujeloNo ratings yet

- Overview of Gastrointestinal Tract Perforation 2023Document51 pagesOverview of Gastrointestinal Tract Perforation 2023Ricardo Javier Arreola PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Chap01 PDFDocument3 pagesChap01 PDFaldiansyahraufNo ratings yet

- ObstetricsDocument48 pagesObstetricsمنوعاتNo ratings yet

- Appendicits Case Study LATEST CHANGESDocument26 pagesAppendicits Case Study LATEST CHANGESsaleha sultanaNo ratings yet

- Management Acute General Peritonitis: THE OFDocument6 pagesManagement Acute General Peritonitis: THE OFNadia Puspita DewiNo ratings yet

- Sasbel 3.1 EmergencyDocument13 pagesSasbel 3.1 EmergencyRafa AssidiqNo ratings yet

- Referat AppendicitisDocument21 pagesReferat Appendicitisyaspie100% (2)

- Acute Appendicitis: Michael Alan Cole Robert David HuangDocument10 pagesAcute Appendicitis: Michael Alan Cole Robert David HuangandreaNo ratings yet

- 1.app A Short Survey On Incidence of Appendicitis in Basrah ProvinceDocument14 pages1.app A Short Survey On Incidence of Appendicitis in Basrah ProvinceImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Peritoneal CirculationDocument2 pagesPeritoneal CirculationM Rizal Isburhan0% (1)

- Proceedings: BuroerDocument8 pagesProceedings: Buroeralifa ishmahdinaNo ratings yet

- لقطة شاشة 2022-04-21 في 11.10.40 صDocument55 pagesلقطة شاشة 2022-04-21 في 11.10.40 صEngi KazangyNo ratings yet

- Referat PeritonitisDocument19 pagesReferat PeritonitisAdrian Prasetya SudjonoNo ratings yet

- Treatise on the Anatomy and Physiology of the Mucous Membranes: With Illustrative Pathological ObservationsFrom EverandTreatise on the Anatomy and Physiology of the Mucous Membranes: With Illustrative Pathological ObservationsNo ratings yet

- December 2009 One FileDocument346 pagesDecember 2009 One FileSaad MotawéaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on Dengue Fever among Slum DwellersDocument11 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes and Practices on Dengue Fever among Slum DwellersMahadie Hasan JahadNo ratings yet

- Ebola Research PaperDocument57 pagesEbola Research PaperTony Omorotionmwan Airhiavbere100% (1)

- Red Eye With Normal VisionDocument58 pagesRed Eye With Normal VisionDiskaAstariniNo ratings yet

- Viruses 13 00281 v2Document14 pagesViruses 13 00281 v2Mhd Fakhrur RoziNo ratings yet

- CSOM of Middle Ear Part 2Document55 pagesCSOM of Middle Ear Part 2Anindya NandiNo ratings yet

- ICU Guide OneDocument318 pagesICU Guide OneSamar DakkakNo ratings yet

- Nyx, A Noctournal - 8: SkinDocument158 pagesNyx, A Noctournal - 8: SkinNyx, a noctournalNo ratings yet

- Imovax Polio Larutan Injeksi 0,5 ML (Pre-Filled Syringe)Document1 pageImovax Polio Larutan Injeksi 0,5 ML (Pre-Filled Syringe)kemalahmadNo ratings yet

- Susceptible Exposed Infected Recovery (SEIR) Model With Immigration: Equilibria Points and Its ApplicationDocument8 pagesSusceptible Exposed Infected Recovery (SEIR) Model With Immigration: Equilibria Points and Its ApplicationAkhmad Riki FadilahNo ratings yet

- Seminar Paper.1Document38 pagesSeminar Paper.1Geckho AdeNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Patient with Sepsis and CellulitisDocument3 pagesNursing Care Plan for Patient with Sepsis and CellulitisMichaelaKatrinaTrinidadNo ratings yet

- 1.7B AppendixDocument4 pages1.7B AppendixDulce Kriselda E. FaigmaniNo ratings yet

- Royal Pain: Egypt at A GlanceDocument3 pagesRoyal Pain: Egypt at A GlanceRajendra PilludaNo ratings yet

- 4 SporozoaDocument42 pages4 SporozoaFranz SalazarNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Clinical GuidelinesDocument66 pagesDiabetes Clinical GuidelinesfamtaluNo ratings yet

- Acute Otitis Media: Dr. Ajay Manickam Junior Resident RG Kar Medical College HospitalDocument20 pagesAcute Otitis Media: Dr. Ajay Manickam Junior Resident RG Kar Medical College HospitalchawkatNo ratings yet

- #Complications of Suppurative Otitis MediaDocument8 pages#Complications of Suppurative Otitis MediaameerabestNo ratings yet

- Comparison of symptoms and causes of COVID-19, flu, cold and GI illnessDocument1 pageComparison of symptoms and causes of COVID-19, flu, cold and GI illnesskelvinkinergyNo ratings yet

- PEDIADRUGDocument6 pagesPEDIADRUGPatrice LimNo ratings yet

- The Clostridium Specis.Document38 pagesThe Clostridium Specis.علي عبد الكريم عاصيNo ratings yet

- MRI findings in limb-restricted vasculitisDocument4 pagesMRI findings in limb-restricted vasculitisMithun CbNo ratings yet