Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Chilean Winter: Sergio Villalobos-Ruminott

Uploaded by

sergio villalobos ruminott0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

85 views5 pages1. Student protests in Chile began in 2011 over issues with the country's secondary and higher education systems. Protests were led by student federations and involved both secondary and university students.

2. The protests have been massive in scale, with some demonstrations attracting over 100,000 people. Students have barricaded themselves in hundreds of schools and staged frequent large demonstrations with choreographed marches.

3. The protests challenge Chile's neoliberal education model implemented since Pinochet that promoted privatization and deregulation, leading to a decline in quality and corruption through ties between politicians, banks, and private universities.

Original Description:

Original Title

villalobosruminott_chileanwinter

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. Student protests in Chile began in 2011 over issues with the country's secondary and higher education systems. Protests were led by student federations and involved both secondary and university students.

2. The protests have been massive in scale, with some demonstrations attracting over 100,000 people. Students have barricaded themselves in hundreds of schools and staged frequent large demonstrations with choreographed marches.

3. The protests challenge Chile's neoliberal education model implemented since Pinochet that promoted privatization and deregulation, leading to a decline in quality and corruption through ties between politicians, banks, and private universities.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

85 views5 pagesThe Chilean Winter: Sergio Villalobos-Ruminott

Uploaded by

sergio villalobos ruminott1. Student protests in Chile began in 2011 over issues with the country's secondary and higher education systems. Protests were led by student federations and involved both secondary and university students.

2. The protests have been massive in scale, with some demonstrations attracting over 100,000 people. Students have barricaded themselves in hundreds of schools and staged frequent large demonstrations with choreographed marches.

3. The protests challenge Chile's neoliberal education model implemented since Pinochet that promoted privatization and deregulation, leading to a decline in quality and corruption through ties between politicians, banks, and private universities.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

11 R a d i c a l P h i l o s o p h y 1 7 1 ( J a n u a r y / F e b r u a r y 2 0 1 2 )

tunnel, between social movements everywhere. Wormholes complete the encounter,

transmit messenger particles that unite all struggles across the planet. Charged particles

transmit negative, repulsive energy, frequently saying to other particles move apart;

yet every particle also has an opposite charge, has powers of attractions that say come

together. In our contemporary, ever-expanding urban universe, little loops of energy

generate incredible force; they literally make the world go around, light it up with

electricity. It`s time, perhaps, for political struggles of the type exemplifed in urban

occupations to energize this new planetary charge, and convert it into unprecedented

cosmic singularity - into our own concrete expressionism. Behind the mask lies more

than fesh. Behind the mask lies an idea, and that idea circulates though the wormhole.

There, it really is bulletproof.

Notes

1. The Guy Fawkes mask donned by the protesters is taken from the revolutionary hero of David Lloyd

and Alan Moores graphic novel V for Vendetta, set in a dystopian future Britain, and the subsequent

2006 flm directed by James McTeigue. My title is also an allusion to this work.

2. See Andy Merrifeld, Crowd Politics, or, 'Here Comes Everybuddy`, New Left Review 71, September/

October 2011, pp. 103-14.

The Chilean winter

Sergio Villalobos-Ruminott

S

ince the beginning of 2011, student mobilizations in Chile have occupied the

centre of public debate. On the one hand, most of the population, along with

most of the political parties currently opposed to Sebastin Pieras government,

agree on the crisis of secondary and higher education in a country that has been widely

praised for fostering democratization and economic prosperity after the dark decades of

Pinochet`s dictatorship (1973-89). On the other hand, there seems to be little agreement

on what this crisis actually means, and even the government recognizes the necessity

for substantial changes in the relationship between the state and the general system

of education. At the same time, this new series of protests complements and further

radicalizes those that took place in 2006, protests called the Penguin Revolution with

reference to the secondary students who played a crucial role in the demonstrations.

What appears to be new in the present conjuncture is the involvement of students from

both secondary and post-secondary institutions, public and private. The breadth and

scale of participation are an indication of the nature of the crisis.

The current cycle of protests began in April 2011, when the CONFECH (Chiles

confederation of university students) decided to strike, demanding improvements in

the government`s fnancial plans and changes to the distribution of scholarships, social

benefts and transportation passes. CONFECH represents students from traditional uni-

versities, of which FEUC (Students Federation of the Catholic University of Chile) and

FECH (Students Federation of University of Chile) are the most important, along with

FEC, from the University of Conceptin, in the south of the country. Very quickly many

other universities and professional institutes got involved, along with secondary students

from both private and public sectors; CONFECH actions were relayed by protests and

12

sit-ins organized by federations of high-school students (CONES and ACES), and by June

the whole system of education was paralysed. The Chilean Winter had begun. Camila

Vallejo, a communist militant, along with Giorgio Jackson, a socialist one, are the most

visible leaders of a movement that challenges the hierarchical structures of political

parties and other representative organizations and insists on horizontal decision-making

processes (basismo), based on a commitment to democratic de-centralism.

The scale and impact of the protests are hard to exaggerate. Students have barricaded

themselves into hundreds of schools, blocking access to teachers and staff.

1

They have

staged dozens of massive demonstrations, which have often incorporated elaborate cho-

reographies involving thousands of people; the largest gatherings, from 10 to 25 August,

numbered from 100,000 to 1 million marchers.

2

These protests are far from over, and in

November 2011 began intersecting with other regional mobilizations, notably in Brazil

and Columbia.

After many attempts to invalidate the movements claims and legitimacy, on 19 July

the government replaced its minister of education (Joaqun Lavn, an ex-presidential

candidate for the right wing) with justice secretary Felipe Bulnes, and launched a

round-table discussion strategy, from which nothing good has yet come. The rapid

growth of the protest movement and the multiplication of public meetings and of

innovative mass actions, along with some international pressure, have reopened the

wounds left from Chile`s unfnished transition to democracy; by way of reaction, they

have also helped revive the aggressively anti-communist rhetoric of the hard right, those

who still consider Pinochet a national hero. This re-politicization of public debates, with

its distinct streak of anachronism, has revived memories of the fght against military

dictatorship in the national protests of the 1980s. For their part, student protestors draw

attention to the structural complicity between the government and the main opposition

parties, and remain deeply sceptical of formal political procedures, especially following

the suppression of the 2006 March of the Penguins by the government of Michel

Bachelet (a socialist who belongs to the Concertation for Democracy - a set of anti-

Pinochet parties that is today in opposition).

The most urgent task for both the government and the opposition, therefore, is not

to fnd a solution to the students` claims but to neutralize their direct political role,

by redirecting the debate back to the formal-democratic institutions framed by the

constitutional order set up to replace Pinochets regime. Repeating the sacred principle

of security that underlies the neoliberal regimes urbe et orbi, they insist that it is in the

National Congress and between the professional politicians that the debate must take

place, and not in the streets, among juvenile proto-criminals.

From its brutal inauguration until its dying day, Pinochets dictatorial regime was

characterized by its reformulation of the nations social contract. With the new constitu-

tion of 1980 and with systematic implementation of neoliberal priorities (privatization

of the public sector, deregulation of the economy, liberal tax policies, etc.), it was

only a matter of time before something similar happened to the education sector. Sure

enough, promotion of privatization as a means of compensating for the lack of fnancial

resources resulting from the new orientation of the state - the distinctive feature of the

new political economy blessed by the Chicago Boys and enthusiastically implemented in

Chile in the 1980s - was soon extended to apply to education policies.

3

The euphemism

used to name that process was rationalization: in this context, rationality involves an

unfounded assumption about the virtues of market forces and the dynamic and effcient

character of the private sector, basis for the reckless wager that its promotion to a com-

manding position in a new competitive education sector would drive up standards

and improve the quality of teaching and research.

By the 1990s, with the new transitional governments, this tendency was accentuated

thanks to what was presented as a new social contract between the state, the private sector

13

and the universities.

4

If the proliferation of private institutions of higher education was a

consequence of the dictatorships policies, the deregulation proposed and radicalized in

the 1990s explains not only the impoverishment of traditional and public universities but

also a decline in quality in indicator after indicator (undergraduate teaching, libraries,

laboratories, and professional and academic careers in general). The intervention of the

private sector, contrary to original expectations, came to be widely seen as the cause of

the corruption and collapse in standards that characterizes the current situation.

The corruption at issue here,

however, refers less to a moral

issue than to an effectively

criminal conspiracy between

the state and the private sector.

This conspiracy is apparent in

the circulation of the elites;

that is to say, in the fact that the

same politicians responsible for

making decisions regarding the

education system also belong to,

or have belonged to, the boards

directing these institutions.

5

Along with this, many Chileans

are scandalized by the fnancial arrangements whereby the banks, with state guarantees,

lend money to students at extortionate interest rates. Today these rates make the cost of

higher education in Chile, proportionally speaking, the most expensive in the world.

6

The banks stand to make a killing, risk-free: if students default, then the state steps in

to pay off the balance of their loan - a policy that fts very nicely with the widespread

practice of hiring infuential political fgures to the boards of fnancial institutions. On

the other hand, it is estimated that more than 40 per cent of the student population

will not be able to fnish their degrees, which makes the prospect of repayment still

more remote. The whole confguration of student debt now operates as a mechanism

whereby banks proft through a process of what David Harvey calls accumulation by

dispossession. Systematic extension of the student debt relation has become a structural

mechanism in the current accumulation process.

7

Such accumulation through exceptionally punitive forms of debt can also be read as

marking a fnal break with the old liberal apparatus of ideological interpellation - that

form of interpellation that promised a fair and socially responsible distribution of

income, combined with the promise of social mobility through educational qualifcation.

As the possibilities for social mobility tend to vanish, so then the whole argument of

modernization is disclosed as an argument that overtly and emphatically complements

the process of popular dispossession and the concentration of capital. Despite (or because

of) the praise Chile has earned from the World Bank and the IMF over the past couple of

decades, its distribution of income is now one of the most unequal in the world.

8

If reduction of human beings to the status of human resources and human assets is

at the heart of neo liberal biopolitics (to invoke Foucaults analysis

9

), then nowhere has

this process gone further than in Chile, where the conversion of students into customers

and debtors is virtually complete.

10

The same thing could be said about the precariza-

tion and casualization of academic labour and the emergence of a post-Fordist regime

in which academic careers are regulated through profoundly exploitative contractual

regulations - a career status that in Chile has acquired the name taxicab professorship`.

What is at stake in todays student mobilizations, therefore, is far more than a

discrete series of economic claims (lower interest rates for their loans, free public

transportation, better scholarship programs, etc.). What is essential is the demand for

14

free higher education for all, a demand that has been criticized as unrealistic and naive;

this demand goes right to the heart of calls for a reformulation of the social contract

inherited from Pinochets regime. The only way to implement free education for all is

through a renationalization of the copper companies and through essential associated

reforms, but to do that it is necessary to demolish the political equilibrium that still

preserves the illegitimate constitution of 1980. This is why the student mobilizations are

inherently political, and subversive: they expose the unjust distribution of wealth, and

the real purpose of those mechanisms of appropriation and accumulation shaping the

current class confguration of Chilean society. However spectacular the recent celebra-

tions of Chiles bicentenary, they could not hide the actual reality at issue in the tempo-

rality of capitalism. Pieras government has not listened to the students and perpetually

challenges their claim for free education for all, replacing it with the empty notion of

a better quality education for all. The notion of quality operates in the governments

discourse in very much the same way as the notion of excellence does in what Bill

Reading calls the University in Ruins, as an ideological device that means more or less

whatever you want it to mean, if not nothing at all.

11

I would like to conclude, however, with an observation regarding what I consider

to be the limits of this movement. On one hand, the mobilizations can be treated as

an eruption of the political into the midst of neoliberal Chilean democracy - that is, a

regime organized around a small number of fnancial institutions belonging to a few

rich families, working in conjunction with a few privileged foreign companies. The

mobilizations thus serve to make visible what was formerly invisible, producing what

Rancire calls a redistribution of the sensible. On the other hand, though, after more

than eight months of demonstrations, the mobilization has fallen into a sort of routine.

Its charismatic leadership has acquired a recognizable place in the political debate, and

the government (together with the opposition) has largely succeeded in recasting that

debate around the confguration of the budget for the new fscal year. The students have

good reasons for their rejection of political parties, but this, compounded by their rela-

tive inability to articulate their demands with other sectors of the population, has also

served to isolate them and to weaken their position; the coming holiday season will also

disperse many students, and take some of the immediate pressure of the government.

Nonetheless, I put the word limits in scare quotes because the inability of students

so far to articulate themselves as part of a counter-hegemonic bloc is actually not their

responsibility but a failure of political understanding more broadly. If real victory

requires more than a capacity merely to interrupt the distribution of the sensible, any

romanticism of the multitude` is also insuffcient to grasp what is at stake here. On the

other hand, the return of what Daniel Bensad might call the question of strategy need

not involve a choice between starkly opposed options: either traditional parties or a new

messianic political organization; either the self-assertion of the multitude or a more

traditional form of class antagonism; either the traditional dogmatic Left or the chas-

tened, reformist or realistic socialism of the new millennium. To resolve these tensions

is less the responsibility of the students than of the wider radical Left, one that is able

to contest the ongoing savagery of capitalist accumulation without ceasing to imagine a

better and more equitable world.

Notes

1. Gideon Long, Chiles Student Protests Show Little Sign of Abating, BBC News, 25 October 2011,

www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-15431829.

2. See, for example, the online edition of Clarin.com: Bajo una intensa lluvia y mucho fro, miles

de estudiantes marcharon por Santiago, 18 August 2011, www.clarin.com/mundo/intensa-estudi-

antes-marchan-capital-chilena_0_538146385.html. Cf. Dozen Injured after Clashes on Day Two

Of Chilean Strike, Guardian, 25 August 2011, www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/aug/26/two-chile-

nationwide-strike-violence; Chile Strike: Clashes Mar Antigovernment Protest, BBC News, 26

August 2011, www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-14677953.

15 R a d i c a l P h i l o s o p h y 1 7 1 ( J a n u a r y / F e b r u a r y 2 0 1 2 )

3 Thanks to Anustup Basu for his generous help in the preparation of this article. See, in particular,

Carlos Ruiz, De la repblica al mercado. Ideas educacionales y polticas en Chile, LOM Ediciones,

Santiago, 2010.

4. Jos Joaqun Brunner, Hernn Courard and Cristin Cox, Estado, mercado y conocimientos: polti-

cas y resultados de la educacin superior chilena 19601990, FLACSO, Santiago, 1992.

5. Mara Olivia Monckeberg, El negocio de las universidades en Chile, Debate, Santiago, 2007. This

volume complements a former one entitled La privatizacin de las univer$idades en Chile. Una

historia de poder, dinero e inuencias, Copa Rota, Santiago, 2005.

6. Data from the OECD states that, at relative prices, higher education in Chile is the most expensive

in the world. With an average cost of US$ 3,400 yearly, the rate of domestic tuition fees is equivalent

to 22.7 per cent of GDP per capita, higher than nations such as United States, Australia and Japan

(Chile, la educacin superior ms cara del nundo, http://aquevedo.wordpress.com/2011/07/05/chile-

la-educacin-superior-ms-cara-del-mundo/). The cost of tuition has increased by over 100 per cent in

the public sector and even more in the larger private sector over the last ten years.

7. David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005.

8. See the CIA World FactBook, www.indexmundi.com/chile/distribution_of_family_income_gini_

index.html.

9. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collge de France, 19781979, Picador,

New York, 2010.

10. Particularly telling is the doctoral dissertation of the current president of Chile, Sebastin Piera,

The Economics of Education in Developing Countries, Department of Economics, Harvard Uni-

versity, 1976. See also Sebastin Piera, El Costo Econmico del 'Desperdicio de Cerebros`,

Cuadernos de Economa, vol. 15, no. 46, 1978, pp. 349-405.

11. Bill Readings, The University in Ruins, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1996.

Occupy time

Jason Adams

U

ntil recently a casual observer might have thoght that Occupy had developed

a time-management problem: it was increasingly managed by movement a

static, essentially timeless image of space. While Occupy Wall Street initially

began with the declaration that 17 September would be the starting date and that it

would continue for an unspecifed period, the focus soon shifted to a general strategy

of occupying public space. While this produced many victories, a certain ossifcation

also emerged. What should have been one tactic among others began to harden into an

increasingly homogenous strategy. For many of those involved, maintaining this spatial

focus became the sine qua non of the movement, even in the face of the changing

of the seasons and the nationwide campaign of police evictions. In nearly every

history-altering moment of the past, from the Paris Commune to the anti-globalization

movement, it was the element of time that proved most decisive. Indeed, events of the

past that are narrated as failures can be renarrated from the standpoint of the possible

successes they have left behind, which remain to be actualized.

Rather than maintaining this spatial strategy at all costs, what is most interesting

about Occupy now is that it is increasingly complicating static images of space by

occupying time. This has meant a shift to a more fuid, tactical approach, one not only

appropriate to the specifcs of constantly changing situations deployed from above,

but one that, more importantly, allows it to bring forth new ones, from below. Indeed,

You might also like

- Civil Rights Ib History NotesDocument14 pagesCivil Rights Ib History Notesmimi inc100% (1)

- Larouche - Children of Satan 4Document25 pagesLarouche - Children of Satan 4jesse deanNo ratings yet

- Shock Doctrine AnalysisDocument34 pagesShock Doctrine AnalysisCostache Madalina AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Towards a Green Democratic Revolution: Left Populism and the Power of AffectsFrom EverandTowards a Green Democratic Revolution: Left Populism and the Power of AffectsNo ratings yet

- Public International Law CasesDocument25 pagesPublic International Law CasesMaria Reylan Garcia100% (1)

- Clandestine in Chile - Gabriel Garcia Marquez PDFDocument130 pagesClandestine in Chile - Gabriel Garcia Marquez PDFDavid Insua-cao100% (1)

- Habermas New Social MovementsDocument5 pagesHabermas New Social Movementssocialtheory100% (1)

- Destabilizing Chile: The United States and The Overthrow of AllendeDocument20 pagesDestabilizing Chile: The United States and The Overthrow of AllendeGökçe ÇalışkanNo ratings yet

- Fraser, A Triple Movement. Parsing The Politics of Crisis After Polanyi-2Document14 pagesFraser, A Triple Movement. Parsing The Politics of Crisis After Polanyi-2Julian GallegoNo ratings yet

- Everyday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public LifeFrom EverandEveryday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

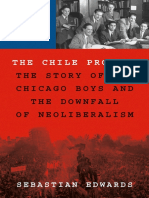

- Edwards - The Chile Project - The Story of The Chicago Boys and The Downfall of NeoliberalismDocument350 pagesEdwards - The Chile Project - The Story of The Chicago Boys and The Downfall of NeoliberalismRodrigo Enrich De Castro100% (1)

- Brian Loveman-Chile The Legacy of Hispanic Capitalism (Latin American Histories) (2001)Document445 pagesBrian Loveman-Chile The Legacy of Hispanic Capitalism (Latin American Histories) (2001)Felipe Sánchez100% (1)

- Neoliberal Resilience: Lessons in Democracy and Development from Latin America and Eastern EuropeFrom EverandNeoliberal Resilience: Lessons in Democracy and Development from Latin America and Eastern EuropeNo ratings yet

- Incomplete Democracy: Political Democratization in Chile and Latin AmericaFrom EverandIncomplete Democracy: Political Democratization in Chile and Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Chilean Students Rise UpDocument4 pagesChilean Students Rise UpAlastair StephensNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Student Discontent Chilean Student P PDFDocument37 pagesDemocracy and Student Discontent Chilean Student P PDFGeman ColmenaresNo ratings yet

- Cabalin 3Document26 pagesCabalin 3Everton MeiraNo ratings yet

- Public Education and Student Movements The Chilean Rebellion Under A Neoliberal ExperimentDocument18 pagesPublic Education and Student Movements The Chilean Rebellion Under A Neoliberal ExperimentRodrigo Carlos Cornejo ChavezNo ratings yet

- Social Movements and The Pandemic 2 PDFDocument7 pagesSocial Movements and The Pandemic 2 PDFNOENo ratings yet

- A Brief History of 15Document4 pagesA Brief History of 15biplab1971No ratings yet

- Puga - Ideological InversionDocument27 pagesPuga - Ideological InversionCAMILA FIORELLA MORENO ESPINOZANo ratings yet

- Becoming Hijas de La Lucha Political Subjectification Affective Intensities and Historical Narratives in A Chilean All Girls High SchoolDocument28 pagesBecoming Hijas de La Lucha Political Subjectification Affective Intensities and Historical Narratives in A Chilean All Girls High Schoolhiginio castroNo ratings yet

- Social Upheaval in ChileDocument11 pagesSocial Upheaval in ChileIgnacio LabaquiNo ratings yet

- Privatization and Access: The Chilean Higher Education Experiment and Its DiscontentsDocument11 pagesPrivatization and Access: The Chilean Higher Education Experiment and Its DiscontentsPablo Riveros ArgelNo ratings yet

- S23 Education To Govern 1st PrintingDocument96 pagesS23 Education To Govern 1st PrintingNyarlathotep Caos rastejanteNo ratings yet

- BA Politics - VI Sem. Additional Course - New Social MovementsDocument59 pagesBA Politics - VI Sem. Additional Course - New Social MovementsAnil Naidu100% (2)

- Ca A e A Es: Ed Tlon L Al RN IVDocument20 pagesCa A e A Es: Ed Tlon L Al RN IVJosé R.No ratings yet

- Manifesto Framing StatementDocument20 pagesManifesto Framing Statementepcferreira6512No ratings yet

- 15-08-11 Chile at The CrossroadsDocument3 pages15-08-11 Chile at The CrossroadsWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- With Allies Like These - Reflections On Privilege Reductionism - LinchpinDocument21 pagesWith Allies Like These - Reflections On Privilege Reductionism - LinchpinheadronefishNo ratings yet

- Pingkian 01-01 FINAL3 PDFDocument289 pagesPingkian 01-01 FINAL3 PDFRolando TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Reclaim Education #6Document2 pagesReclaim Education #6International Student MovementNo ratings yet

- Nancy Fraser A TRIPLE MOVEMENT?Document14 pagesNancy Fraser A TRIPLE MOVEMENT?Vitalie SprinceanaNo ratings yet

- General Aims: TH THDocument4 pagesGeneral Aims: TH THFelipeNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Waves Read DraftDocument24 pagesBreaking The Waves Read DraftKarl BaldacchinoNo ratings yet

- Cap KDocument118 pagesCap KPeter ZhangNo ratings yet

- Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in The Internet Age. by Manuel CastellsDocument6 pagesNetworks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in The Internet Age. by Manuel Castellsapi-313434876No ratings yet

- CabalinDocument11 pagesCabalinEverton MeiraNo ratings yet

- Education From Within and Without (Pp. 229-242) - The United States of AmericaDocument21 pagesEducation From Within and Without (Pp. 229-242) - The United States of AmericaTatiana AvendañoNo ratings yet

- Adornotheory Crit Ped 2018Document13 pagesAdornotheory Crit Ped 2018MilaziNo ratings yet

- Bolivia's Institutional Transformation: Contact Zones, Social Movements, and The Emergence of An Ethnic Class ConsciousnessDocument23 pagesBolivia's Institutional Transformation: Contact Zones, Social Movements, and The Emergence of An Ethnic Class ConsciousnessGabriel Vinicius Chimanski dos SantosNo ratings yet

- ComparativePoliticsofEducation IntroductionDocument23 pagesComparativePoliticsofEducation IntroductionHenriqueArzaniNo ratings yet

- Apple 2005Document24 pagesApple 2005Alex MadisNo ratings yet

- 08-08-11 Noam Chomsky - Public Education Under Massive Corporate AssaultDocument6 pages08-08-11 Noam Chomsky - Public Education Under Massive Corporate AssaultWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- Connell: "Understanding Neoliberalism"Document8 pagesConnell: "Understanding Neoliberalism"CaitlinNo ratings yet

- Gitlin Occupy's Predicament: The Moment and The Prospects For The Movement1Document23 pagesGitlin Occupy's Predicament: The Moment and The Prospects For The Movement1derivla85No ratings yet

- Dual Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Institutionalized Regimes in Chile and Mexico, 1970–2000From EverandDual Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Institutionalized Regimes in Chile and Mexico, 1970–2000No ratings yet

- The Return of The Student Movement As A Social ForceDocument3 pagesThe Return of The Student Movement As A Social ForceChristopher CarricoNo ratings yet

- The Uprising of the Pandemials: Human Cycles and the Decade of TurbulenceFrom EverandThe Uprising of the Pandemials: Human Cycles and the Decade of TurbulenceNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University PressDocument22 pagesCambridge University PressSimon Kévin Baskouda ShelleyNo ratings yet

- Human Rights and Transitional Justice in Chile 1St Ed 2022 Edition Rojas Full ChapterDocument67 pagesHuman Rights and Transitional Justice in Chile 1St Ed 2022 Edition Rojas Full Chapterjudy.hammons132100% (6)

- Charles Hale-NeoliberalDocument19 pagesCharles Hale-Neoliberalkaatiiap9221100% (1)

- CubaDocument28 pagesCubaANAHI83No ratings yet

- Polar 05Document19 pagesPolar 05Lana GitarićNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.152.81.122 On Sat, 13 Feb 2021 00:59:59 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.152.81.122 On Sat, 13 Feb 2021 00:59:59 UTCAlejandro GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Income, Education and DemocracyDocument62 pagesIncome, Education and DemocracyHector LaresNo ratings yet

- Torche Florencia Social Mobility in ChileDocument30 pagesTorche Florencia Social Mobility in ChileGuillermo RuthlessNo ratings yet

- HISTOPAPER1 - Analysis of "I Hate My Country" by DiamanteDocument5 pagesHISTOPAPER1 - Analysis of "I Hate My Country" by DiamantereslazaroNo ratings yet

- Full Text 01Document106 pagesFull Text 01María Alejandra ValNo ratings yet

- International Political Science Review 2009 Teichman 67 87Document21 pagesInternational Political Science Review 2009 Teichman 67 87Vth SkhNo ratings yet

- Feminism and Gender Policies in Post-Dictatorship Chile (1990-2010)Document29 pagesFeminism and Gender Policies in Post-Dictatorship Chile (1990-2010)catalinaNo ratings yet

- Becoming Precarious in Neoliberal BiopoliticsDocument7 pagesBecoming Precarious in Neoliberal BiopoliticsJoe RigbyNo ratings yet

- Wiley Center For Latin American Studies at The University of MiamiDocument5 pagesWiley Center For Latin American Studies at The University of MiamiBruno Rojas SotoNo ratings yet

- Ahmad1971 Theories of CounterinsurgencyDocument6 pagesAhmad1971 Theories of CounterinsurgencybaptistesellierNo ratings yet

- Teaching Marxism in A Neoliberal Era.5 PHAV 17-18Document36 pagesTeaching Marxism in A Neoliberal Era.5 PHAV 17-18NOENo ratings yet

- Habermas - Conservatism and Capitalist Crisis PDFDocument12 pagesHabermas - Conservatism and Capitalist Crisis PDFheinoostveenNo ratings yet

- Occupay AmericaDocument4 pagesOccupay AmericaIqbal Mahmud RanaNo ratings yet

- Brown Post W SovereigntyDocument22 pagesBrown Post W SovereigntyMauricio Castaño BarreraNo ratings yet

- Listen To This 3Document139 pagesListen To This 3Doctor DangNo ratings yet

- The Lonely Success StoryDocument84 pagesThe Lonely Success StoryDuende ParraguezNo ratings yet

- Commanding Heights Episode 2Document28 pagesCommanding Heights Episode 2Mike GarcíaNo ratings yet

- A Psychosocial Interpretation of Political ViolenceDocument18 pagesA Psychosocial Interpretation of Political ViolenceMaria Alejandra Tapia MillanNo ratings yet

- If You Want To Do As AllendeDocument2 pagesIf You Want To Do As AllendeKent Ruel DelastricoNo ratings yet

- Chile Anatomy of An Economic Miracle, 1970-1986Document3 pagesChile Anatomy of An Economic Miracle, 1970-1986alexandrosminNo ratings yet

- Naomi Klein: The Shock Doctrine: Naomi Klein On The Rise of Disaster CapitalismDocument14 pagesNaomi Klein: The Shock Doctrine: Naomi Klein On The Rise of Disaster CapitalismvetvetNo ratings yet

- Listen to This 3 高级听力 教师用书 听力原文Document51 pagesListen to This 3 高级听力 教师用书 听力原文666 SarielNo ratings yet

- Hayek Chile 03 11 11Document32 pagesHayek Chile 03 11 11Payam Sharifi100% (1)

- Autopista Case Grupo 1Document32 pagesAutopista Case Grupo 1Amigos Al CougarNo ratings yet

- 03 Brender 2010 Chile Formation of The Chicago Boys PDFDocument13 pages03 Brender 2010 Chile Formation of The Chicago Boys PDFpagieljcgmailcomNo ratings yet

- Chile ThesisDocument70 pagesChile ThesisJosh Andinista StiltnerNo ratings yet

- Born Under PunchesDocument12 pagesBorn Under PunchesBruce WilsonNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics) Lisa Baldez - Why Women Protest - Women's Movements in Chile (2002, Cambridge University Press) PDFDocument255 pages(Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics) Lisa Baldez - Why Women Protest - Women's Movements in Chile (2002, Cambridge University Press) PDFVanessa TessadaNo ratings yet

- The Mapuche Struggle For Land and Recognition - A Legal AnalysisDocument53 pagesThe Mapuche Struggle For Land and Recognition - A Legal AnalysisLilla MagyarNo ratings yet

- South America ChileDocument133 pagesSouth America ChilegoblinrusNo ratings yet

- Collins & Lears - Pinochet's GiveawayDocument8 pagesCollins & Lears - Pinochet's GiveawayGonzalo SáenzNo ratings yet

- Stitching Truth LessonsDocument16 pagesStitching Truth LessonsFacing History and OurselvesNo ratings yet

- 2.V.2 Stern, S. J. (2016) Memory. Radical History Review, 2016 (124), 117-128 PDFDocument13 pages2.V.2 Stern, S. J. (2016) Memory. Radical History Review, 2016 (124), 117-128 PDFSergio Daniel Paez DiazNo ratings yet

- Hush Puppies ChileDocument18 pagesHush Puppies Chilegm_krishnanNo ratings yet

- Friedmans School Choice Theory - The Chilean Education SystemDocument29 pagesFriedmans School Choice Theory - The Chilean Education SystemJunrey LagamonNo ratings yet