Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antisocial in Middle School Grade

Uploaded by

Gabriella Dian PedrosaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antisocial in Middle School Grade

Uploaded by

Gabriella Dian PedrosaCopyright:

Available Formats

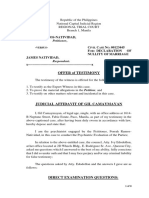

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756 DOI 10.

1007/s10964-008-9272-0

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH

Social Motives Underlying Antisocial Behavior Across Middle School Grades

Jaana Juvonen Alice Y. Ho

Received: 23 October 2007 / Accepted: 8 January 2008 / Published online: 6 February 2008 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008

Abstract The goal of the study was to examine whether social motives (social mimicry, mutual attraction, and unreciprocated attraction) predict changes in antisocial behavior across middle school grades. The 2,003 initial participants (55% girls) were drawn from a larger longitudinal study of urban public school students: 44% Latino, 26% African-American, 10% Asian, 9% Caucasian, and 11% multiracial. Analyses of peer nominations and teacher-rated behavior included ve waves of data between the fall of sixth grade and the spring of eighth grade (n = 1,2601,347 for longitudinal analyses). Supporting the social mimicry hypothesis, students who associated peer-directed aggression with high social status in the beginning of middle school engaged in elevated levels of antisocial conduct during the second year in the new school. Additionally, unreciprocated attraction toward peers who bully others in the beginning of middle school was related to increased antisocial behavior in the last year of middle school. No support was obtained for the mutual attraction hypothesis. The ndings provide insights about possible social motives underlying susceptibility to negative peer inuence. Keywords Antisocial behavior Aggression Peers

Introduction Youth who associate with deviant or antisocial peers are likely to engage in disruptive or delinquent behavior (e.g., Berndt and Keefe 1995; Lahey et al. 1999). Although social selection and inuence are presumed to account for behavioral similarity within peer groups, the underlying mechanisms are less well understood. Specically, little is known about potential motives that encourage youth to model antisocial behaviors of their peers. For example, youth may act tough in order to boost their social status or to impress a particular person they wish to befriend. Alternatively, increased levels of antisocial behavior may reect mutual attraction between peers who each engage in negative social acts. In the current investigation, we test whether these types of social motives can account for changes in antisocial conduct across middle school grades. The assumption guiding our analyses is that the development of behaviors can be understood by investigating social perceptions and choices in the beginning of middle school when youth are trying to nd their niche in the new social setting.

Three Hypotheses for Increased Antisocial Behavior Social Mimicry

J. Juvonen (&) Department of Psychology, University of California, 502 Portola Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA e-mail: j_juvonen@yahoo.com A. Y. Ho Department of Education, University of California, Los Angeles, Box 951521, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA e-mail: AL86ice@ucla.edu

To account for increased rates of delinquency among adolescent males, Moftt (1993) proposed that those with no history of antisocial behavior start mimicking delinquent behaviors of youth who have displayed behavioral problems throughout their childhood. Adolescents mimic these behaviors because presumably they are associated with newfound popularity or prestige among their peers

123

748

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

(Moftt 1993). Several studies document that among young adolescents, antisocial behaviors indeed are associated with perceived popularity or high social status (Gest et al. 2001; Juvonen et al. 2003; La Fontana and Cillessen 1998; Parkhurst and Hopmeyer 1998). Moreover, experimental evidence shows that adolescent males endorse risky behavioral choices consistent with the choices made by popular peers (Cohen and Prinstein 2006). Thus, status and power within a group represent motivational pulls that can help us understand mechanisms underlying the inuence of antisocial peers. Compared to traditional ways of considering peer socialization by friends, social mimicry requires no afliation or relationship between individuals. Rather, the deviant peer acts as a distant role model. By mimicking the behaviors of dominant individuals, group members may increase their own social standing by appearing more like those in power (Juvonen and Galvan in press). We presume that engaging in behaviors exhibited by high status peers is particularly critical when youth are trying to t in and establish their status within a new social setting. Hence, we hypothesize that youth entering their rst year of middle school are particularly eager to emulate their high status classmates. If these popular peers engage in antisocial behavior, their inuence would therefore be negative.

Unreciprocated Attraction Unreciprocated attraction toward someone who engages in antisocial behavior is another possible motive that encourages misbehavior. The comparison between mutual versus unidirectional attraction is particularly interesting because one involves a balanced system of relationships and the other an unbalanced one (Heider 1958). Whereas the mutual attraction hypothesis presumes that increased antisocial behavior reects reinforcement of one anothers negative behaviors, the unreciprocated attraction hypothesis assumes that youth engage in the behaviors of the person they wish to befriend (cf. Baumesiter 1982; Goffman 1959; Leary and Kowalski 1990). An unbalanced system of an unreciprocated attraction might therefore push individuals to change their behavior more so than a balanced (i.e., mutual) relationship. Unreciprocated attraction captures unmet social needs and therefore is likely to make youth particularly susceptible to the inuence of the desired friend (Juvonen and Galvan in press). Although youth with no friends may be particularly needy (cf. Wentzel et al. 2004), we presume that anyone who is unsatised with their social relationships is more likely to be inuenced by the one they wish to befriend. Unmet social needs therefore might explain increases in antisocial behavior, especially at times of social reorganization (e.g., when youth transfer to a new school). Hence, we hypothesize that youth, whose desire to afliate with peers engaging in negative social behavior is not reciprocated in the beginning of middle school, are particularly likely to increase their antisocial conduct over time.

Mutual Attraction Alternatively, increased problem behaviors can be attributed to mutual attraction between potentially deviant youth. People are attracted to others who have similar characteristics and those characteristics are likely fostered over time within the relationship (Kandel 1978). Hence, youth with even the slightest antisocial tendencies might seek out one another, and the close contact may then exacerbate their negative behaviors. Although mutual attraction implies a strong emotional bond (e.g., Berndt and Perry 1986), friendships between antisocial youth are not emotionally satisfying (Poulin et al. 1999). Yet, the social exchanges that these youth engage in with one another are nevertheless rewarding. Labeled as deviance training, this type of mutual reinforcement (e.g., smiling and laughing at one anothers inappropriate conduct and engagement in illegal activities) has been studied mainly within dyads or small groups among special populations or at-risk youth (e.g., Dishion et al. 2004; Dishion et al. 1996; Granic and Dishion 2003), but it is also applicable to school contexts inasmuch as antisocial students tend to bond with similar others (Cairns and Cairns 1994). Based on these ndings, we expect that mutual interest to afliate (i.e., attraction) with a schoolmate who engages in antisocial behavior during the rst year of middle school increases subsequent antisocial behavior.

Current Study We test the three hypotheses outlined above to predict changes in antisocial behavior across four time points between sixth and eighth grades. By examining the potential social motives (social mimicry, mutual attraction, and unreciprocated attraction), our approach offers a new way of conceptualizing susceptibility to negative peer inuence. We presume that the sentiments toward peers who engage in negative social behavior contribute to changes in the participants own conduct. Specically, it was hypothesized that the more frequently students view aggressive classmates as high in social status, and the more frequently they wish to afliate with aggressive peers, the more likely their antisocial behavior escalates over time. Whether the mutuality of attraction between the two peers makes a difference in ones susceptibility toward the others negative behaviors was further examined. Based on prior research, we had no reason to expect any one of the hypotheses to be superior to the others.

123

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

749

To test the hypotheses, we rely on a novel procedure that indirectly assesses the three social motives. Specically, we use a peer nomination procedure that assesses the overlap in nominations made by specic individuals (La Fontana and Cillessen 2003). For example, we assess how many times a student nominates the same person for both having high social status (i.e., being cool) and engaging in peerdirected aggression (i.e., bullying) by computing the frequency of such co-nominations. That is, we pair perceptions of behavior with an indicator of a potential motive (social mimicry, mutual attraction, and unreciprocated attraction) and use the frequency of the respective co-nominations as predictors of antisocial behavior over time (see a full description of the procedure in the method section). In addition to our novel procedure to compute conominations, the longitudinal design strengthens the methodological contributions of the current study. The current analyses rely on peer nomination data obtained during the rst semester in a new middle school. We presume that a transition to a new school provides a unique time to examine social dynamics that contribute to peer selection and inuence. At this time of social reorganization, the classmates with whom students afliate likely affect their own reputation and social status at school. The subsequent time points used to assess changes in antisocial behavior, in turn, allow us to examine the effects of initial peer selection and socialization across varying lengths of time. It is possible that social perceptions and choices in the new school predict behavior changes only across the rst year rather than until the end of middle school. Alternatively, some motives may predict behavior changes at shorter time intervals than others. For example, compared to mutual attraction that is likely to be a relevant motive at any time, social mimicry and unreciprocated attraction might be particular relevant motives to change ones behavior while acclimating to the new setting (i.e., across the transition to seventh grade). When predicting changes in behavior over time, it is also critical to rely on more than one source of data to avoid shared method variance. In the current investigation, we rely on two data sources (i.e., students and teachers). While we presume that peer-directed aggression or bullying in the beginning of middle school generalizes into more general antisocial behaviors during the following two years, the less than perfect item overlap between teacherratings of antisocial behavior and peer nominations of bullying also enhances the methodological rigor of the investigation. Finally, our sample allows us to examine important gender and ethnic differences. Because most studies on peer selection and inuence of antisocial behavior have been conducted with adolescent males, it is not clear if the same mechanisms can also account for increases in

antisocial conduct of young adolescent females. We therefore not only take into account gender differences in antisocial behaviors, but also test whether gender moderates the effects of the three proposed mechanisms that might account for increased problem behaviors across the middle school years. Additionally, our large and diverse public school sample allows us to test ethnic differences and whether ethnicity possibly moderates the associations between social motives and behavior changes across different time intervals.

Method Participants Participants were drawn from a large longitudinal study of 2,307 middle school students (45% boys, 55% girls) in greater Los Angeles. Based on self-report, the overall sample was 44% Latino (primarily of Mexican origin), 26% African-American, 10% Asian, 9% Caucasian, and 11% multiracial. Students were recruited from 99 sixthgrade classes in 11 Los Angeles area middle schools that predominately serve an ethnically diverse population. The schools were located in low socioeconomic status communities and were all entitled to federal compensatory educational (Title I) funds. For the larger study, students participated in six time points of data collection and the participation rates ranged between 99% and 75% for Waves 1 and 6, respectively. The 75% participation rate at the last wave of data collection in the spring of eighth grade exceeds the expected retention rate of 59% that accounts for average student mobility within these urban middle schools and is comparable to that of other longitudinal samples of urban, ethnic minority adolescents (see Gutman and Eccles 2007; Roeser and Eccles 1998; Seidman et al. 1994). In the current investigation data collected from ve of the six waves of the larger longitudinal study were included. Given our goal to examine changes in behavior by taking into account the baseline level of antisocial conduct, we did not include data from the spring of sixth grade because teacher ratings of student antisocial behavior were highly stable within the rst year (r = 0.76, p \ 0.01), compared to the subsequent time points (range of r = 0.400.49, p \ 0.01, as shown in Table 1). In our analysis sample, only students with both nomination data and teacher-reported data at each wave were included in the analyses. As a result, the analysis sample size varied across waves. The analysis sample sizes for the Fall of sixth-grade and the Fall and Spring of seventh- and eighthgrades were 2,003, 1,226, 1,347, 1,260, and 1,274, respectively. Data were missing between the fall of sixth

123

750 Table 1 Correlations among the co-nominations and teacher-reported antisocial behaviors Cool bully, 6F Mutual attract, 6F Unrecip. attract, 6F Antisoc. beh., 6F Antisoc. beh., 7F Antisoc. beh., 7S Antisoc. beh., 8F Antisoc. beh., 8S 0.43*** 0.47*** 0.05* 0.09** 0.08** 0.04 0.02 0.12** 0.09** 0.09** 0.10** 0.06* 0.05* 0.12** 0.10** 0.12** 0.11** 0.11** 0.48*** 0.49*** 0.44*** 0.40*** Mutual attract, 6F Unrecip. attract, 6F Antisoc. beh., 6F

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

Antisoc. beh., 7F

Antisoc. beh., 7S

Antisoc. beh., 8F

0.70*** 0.51*** 0.45*** 0.52*** 0.46*** 0.59***

Note: Cool bully, 6F, coolness of bullies in sixth fall; Mutual attract, 6F, mutual attraction toward bullies in sixth fall; Unrecip. attract, 6F, unreciprocated attraction to bullies in sixth fall; Antisoc. beh. 6F, 7F, 7S, 8F, and 8S, teacher-rated antisocial behavior in sixth grade fall, seventh grade fall, seventh grade spring, eighth grade fall, and eighth grade spring, respectively * p B 0.05; ** p B 0.01; *** p B 0.001

grade and the subsequent waves mainly due to student mobility and absence of teacher-ratings. Independent sample t-tests between students teacher-reported antisocial behavior in the Fall of the sixth grade versus in the Spring of seventh- and eighth-grades, revealed that those students who dropped out of the study each school year were more aggressive than those who remained in the study (ts [ 9.00, ps \ 0.001). Hence, our ndings do not necessarily generalize to youth who display the highest levels of antisocial behavior during the rst year in middle school.

that teachers knew students well enough to complete the behavior ratings.

Measures Teacher-rated Antisocial Behaviors The three-item subscale of a shortened version of the Interpersonal Competence Scale (Cairns et al. 1995) was used to measure antisocial behavior. Homeroom teachers who had daily classroom contact with students rated each participant on a 7-point scale from never to always for items such as starts ghts, argues, and gets in trouble. The internal consistency of this 3-item scale was high (average a = 0.89 across waves).

Procedure In sixth-grade classrooms where teachers expressed interest in the study, students took home letters and consent forms that explained the study to their parents. A rafe was conducted on the day of data collection for all students who returned a signed consent form, with or without parental permission to participate, in order to increase the return rate. A total of 3,511 consent forms were distributed and 75% were returned. Of the returned forms, 89% of their parents granted permission for them to participate in the study. Only those who returned a parent consent form and completed an assent form were allowed to participate in the study. Five dollars per participating student were paid to a class fund in the sixth grade, whereas in subsequent years students were personally paid the same amount for their participation in the study. Students completed written questionnaires in a classroom setting. Research assistants were trained undergraduate and graduate students who read aloud the questionnaire items, while another assistant helped individual participants as needed. Fall data collection each year took place several weeks into the school year to ensure that students knew one another well enough to complete the peer nominations and

Peer Nominations As part of a larger peer nomination protocol, students completed peer-nomination items during the Fall of their sixth grade. For each nomination question, students were allowed to write up to four names of classmates from a class roster that was attached to the questionnaire packet. The alphabetical lists included the names of both participating and non-participating students, separated by gender. To assess students perceptions of antisocial behavior, we relied on questions about bullying. Three separate nominations were used to assess direct physical and verbal as well as indirect forms of bullying. Students named grade mates who (a) start ghts or push other kids around; (b) put other kids down or make fun of others; and (c) spread nasty rumors about other kids. The three types of bullying were highly correlated in the Fall of sixth grade and they were therefore combined (a = 0.90).

123

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

751

To get at sixth graders perceptions of social status, we relied on nominations that asked them to list the names of the coolest kids (Juvonen et al. 2003). To assess attraction, we asked participants to name grade mates whom they like to hang out with. By analyzing the reciprocity of the choices for this question (i.e., whether the nominated person also named the target participant), we were able to compute the mutuality of choices. Thus, each student obtained two scores: one indicating the number of mutual nominations and the other the number of unidirectional preferences.

Computing Co-Nominations The number of times that an individual student named the same classmate as cool and engaging in bullying behavior was used to examine the social mimicry assumption. The frequency that a classmate nominated the same individual for bullying and reciprocated that individuals nomination for like to hang out with denoted mutual attraction toward a bully. Unreciprocated attraction to bullies captured the number of times that a student nominated the same classmate for bullying and unreciprocated like to hang out with. Given that students were asked to nominate up to four peers for each question, the number of co-nominations ranged between zero and four. The means of these three co-nominations ranged from M = 0.11 (SD = 0.38) for Mutual Attraction to Bullies to M = 0.36 (SD = 0.74) for Coolness of Bullies. These means were less than one due to the small proportion of students with any co-nominations (N = 552 with any cool-bully co-nominations, N = 203 with any mutual attraction-bully co-nominations, and N = 350 with any unreciprocated attraction-bully co-nominations).

Results Table 1 displays the correlations among the co-nominations in the fall of sixth grade and teacher ratings of antisocial behavior at all ve time points. As shown in the upper left section of Table 1, both sets of co-nominations tapping attraction (mutual and unreciprocated) were moderately correlated with co-nominations indicating Coolness of Bullies (rs = 0.43 and 0.47, ps \ 0.001, respectively), suggesting that youth are frequently attracted to peers who they consider high in social status. The two attraction indicators, in turn, were less strongly related (r = 0.12, p \ 0.01). As indicated earlier, teacher ratings of antisocial behavior, in turn, were fairly stable across the ve time points (see the lower right section of Table 1). Whereas all three co-nominations were related to antisocial behaviors at

seventh grade, only the two nominations assessing attraction to bullies were related to antisocial conduct at eighth grade. In light of these relatively weak bi-variate correlations, it was important to test our main hypotheses by relying on multivariate methods that enabled us to take into account gender and ethnic differences. Hierarchical regression analyses were therefore conducted to examine the contributions of three types of conominations in predicting teacher-rated antisocial behavior across the three years of middle school: (a) To test the social mimicry hypothesis, the contribution of co-nominations between coolness and bullying was examined. (b) To assess the mutual attraction hypothesis, the effect of the co-nominations between reciprocated attraction and bullying was investigated. (c) To test the unreciprocated attraction hypothesis, the contribution of the co-nominations between unreciprocated attraction and bullying was assessed. Gender and ethnicity were accounted for in Step 1 of the analyses. Ethnicity was dummy coded such that Latino students (the largest ethnic group in our sample) served as the reference group. Baseline level (i.e., fall of sixth grade teacher-ratings) of antisocial behavior was also included in Step 1 because our goal was to predict changes in the behavior over time. The co-nominations of interest were, in turn, entered into the second step of the analyses. The interaction terms of gender 9 co-nominations and ethnicity 9 co-nominations were included last to test whether gender or ethnicity moderated any predicted associations. Because there was no support for either gender or ethnic group moderation, the interaction terms were omitted from the tables. The three hypotheses were rst independently tested with separate regression analyses across each of the four waves of data (i.e., fall and spring of seventh and eighth grades). Given that the co-nominations were correlated with one another, the statistically signicant predictors were then combined into one nal set of regressions to assess their independent contributions. Table 2 summarizes the regression analyses for testing the social mimicry hypothesis (i.e., nominating peers who engage in bullying as cool) across the four time points. The signicant gender difference depicted in Table 2 shows that females were less likely to engage in antisocial behavior than males. Ethnic differences in turn showed that compared to Latino students, African-American students were more likely, whereas Asian students were less likely, to be rated by their teachers as engaging in antisocial conduct. Not surprisingly, antisocial behavior in the fall of sixth grade was the strongest predictor of the same behaviors across all four time points. When controlling for all these other known predictors of antisocial conduct, the social mimicry hypothesis was supported. The more frequently students nominated the same peers as both bullies and cool, the more frequently

123

752

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

Table 2 Testing the social mimicry hypothesis: regression analyses predicting teacher-reported antisocial behavior across seventh and eighth grades in middle school Seventh fall N = 1226 b Step 1 Gender White African-American Asian Other/mixed Antisocial behavior, sixth grade fall Step 2 Coolness of bullies, sixth grade fall 0.06** 0.004** 0.07** 0.005** 0.03 0.001 0.02 0.000 -0.09*** -0.03 0.10*** -0.08** -0.04 0.44*** 0.262*** -0.09*** 0.01 0.17*** -0.05* 0.01 0.43*** 0.278*** -0.08** -0.01 0.12*** -0.08** 0.02 0.38*** 0.220*** -0.10*** -0.04 0.18*** -0.07** -0.00 0.33*** 0.202*** DR

2

Seventh spring N = 1347 b DR

2

Eighth fall N = 1260 b DR

2

Eighth spring N = 1274 b DR2

Note: For gender coding, girls = 1 and boys = 0. Ethnic groups were dummy coded against Latino * p B 0.05; ** p B 0.01; *** p B 0.001

their teachers perceived them to engage in antisocial conduct (i.e., ghts, arguments, and disruptive behaviors) at both the fall and spring of seventh grade. However, this nding was not replicated through the eighth grade. That is, although impressions of the high social status associated with bullying predicted increased antisocial conduct for the second year in the school, this was no longer the case by the last year of middle school. The regression analyses provided no support for the mutual attraction hypothesis. That is, changes in antisocial behavior were not predicted by the frequency of co-nominations for bullying and reciprocal nominations for wanting to hang out with. In contrast, there was support for the unreciprocated attraction hypothesis across all four

waves, as shown in Table 3. Controlling for gender and ethnic differences (described above) as well as differences in initial levels of antisocial conduct in the fall of sixth grade, the more frequently students nominated a classmate engaging in bullying as someone they desired to afliate with, and when the peer did not reciprocate the nomination, the more antisocial they acted between the spring of seventh and eighth grades. In other words, the unmet desire to afliate with someone who engages in bullying at the beginning of middle school was related to increased antisocial conduct for three of the four data points across the two years over and above all other predictors. Finally, we conducted a set of regressions that included the two sets of co-nominations that were associated with

Table 3 Testing the unreciprocated attraction hypothesis: regression analyses predicting teacher-reported antisocial behavior across seventh and eighth grades in middle school Seventh fall N = 1226 b Step 1 Gender White African-American Asian Other/mixed Antisocial behavior, sixth grade fall Step 2 Unreciprocated attraction to bullies, sixth grade fall 0.04 0.001 0.07** 0.005** 0.07** 0.005** 0.07** 0.004** -0.08*** -0.04 0.10*** -0.08** -0.04 0.44*** 0.262*** -0.08*** 0.00 0.17*** -0.05* 0.01 0.43*** 0.278*** -0.07** -0.01 0.11*** -0.08** -0.09*** -0.04 0.18*** -0.06* DR

2

Seventh spring N = 1347 b DR

2

Eighth fall N = 1260 b DR

2

Eighth spring N = 1274 b DR2

0.02 -0.00 0.38*** 0.220*** 0.33*** 0.202***

Note: For gender coding, girls = 1 and boys = 0. Ethnic groups were dummy coded against Latino * p B 0.05; ** p B 0.01; *** p B 0.001

123

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

753

Table 4 Testing social mimicry and unreciprocated attraction hypotheses: regression analyses predicting teacher-reported antisocial behavior in middle school Seventh fall N = 1226 b Step 1 Gender White AfricanAmerican Asian Other/mixed Antisocial behavior, sixth grade fall Step 2 Coolness of bullies, sixth grade fall Unreciprocated attraction to bullies, sixth grade fall 0.06* 0.01 0.004 0.05* 0.05 0.007 -0.01 0.08** 0.005** -0.02 0.08** 0.005** -0.09*** -0.03 0.10*** -0.08** -0.04 0.44*** 0.262*** -0.08*** 0.01 0.17*** -0.05* 0.01 0.43*** 0.278*** -0.06** -0.01 0.11*** -0.08** 0.02 0.38*** 0.220*** -0.09*** -0.04 0.18*** -0.06** -0.00 0.33*** 0.202*** DR

2

Seventh spring N = 1347 b DR

2

Eighth fall N = 1260 b DR

2

Eighth spring N = 1274 b DR2

Note: For gender coding, girls = 1 and boys = 0. Ethnic groups were dummy coded against Latino * p B 0.05; ** p B 0.01; *** p B 0.001

changes in behavior. By including them in the same analyses, we were able to assess their independent contributions to behavior changes across the different time points. As shown in Table 4, these two hypotheses each received support, but for different time spans. Consistent with the earlier analyses, the more frequently students considered classmates who engage in bullying as cool, the more their antisocial behavior increased between the fall of sixth grade and the fall and spring of seventh grade. When controlling the effects of coolness, the unreciprocated attraction, in turn, predicted behavior changes for the fall and spring of eighth grade. In other words, the more frequently the students wished to afliate with a bully who did not reciprocate that wish, the more frequently the target participant engaged in antisocial behavior during their last year in middle school.

Discussion The current ndings provide insights about social motives underlying susceptibility to negative peer inuence. We contend that susceptibility partly reects the social desires or needs of youth in a new social setting. Specically, our ndings suggest that during the rst fall in middle school the desire to be similar to high status peers who are aggressive and the unreciprocated desire to afliate with particular peers who engage in aggressive behavior help in part explain increased antisocial conduct. The social processes examined in the current investigation in all likelihood reect choice or selection of peers as well as behavioral inuence by these peers (cf. Hartup 2005),

inasmuch increases in similar behaviors (bullying and antisocial conduct) between the target participants and their chosen peers were examined over time. The novel peer nomination method enabled us to test inter-individual differences in the prediction of antisocial behavior in the school setting. This method provides an indirect way of assessing processes that individuals might not be consciously aware of. By relying on the nomination overlap (i.e., co-nominations made by students), we presume that social choices and perceptions guide behavior. Consistent with this assumption, we nd that during the rst fall in middle school, perceived association between aggressive behavior and high social status predicts increased antisocial conduct during the fall and spring of the second year in that school. Additionally, our ndings show that unreciprocated desire to afliate with particular peers who engage in aggressive behavior in the sixth grade predicts increased antisocial conduct during the last year and a half in middle school. Although it is not clear why the two potential motives predicted behavioral changes of varying intervals, one can speculate that indicators of high social status are particularly powerful at the point when youth are acclimating to the new scene. After all, the concept of social mimicry comes from the study of animals that adopt their behaviors of other species thereby improving their competitiveness in a particular ecological niche (Moynihan 1968). When both co-nominations assessing social mimicry and unreciprocated attraction were simultaneously included in the same regression analyses, unreciprocated attraction predicted subsequent behaviors only after the second year. This nding reects in part the overlap

123

754

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

between the two social motives (i.e., youth wish to afliate with those who they perceive to be popular). But the nding is also consistent with prior studies (Mrug et al. 2004; Warren et al. 2005) suggesting that some peer effects are delayed rather than short-term. To better understand the joint and unique effects of social motives, analyses of the stability of the motives might provide some insights. Motives may change, or even if the motives stay fairly constant, the behaviors that co-vary with perceptions of a desired peer or high social status may vary over time. Analyses of trajectories depicting dynamic relations between social motives and behaviors over time may help us to better understand these time-varying effects. Such analyses were beyond the scope of the present investigation because our methods of obtaining peer nominations changed after the sixth grade, but they should be pursued in subsequent studies. Contrary to the social mimicry and the unreciprocated attraction hypotheses, we obtained no support for the mutual attraction hypothesis. Our analyses indicated that mutual attraction to bullies did not predict any changes in disruptive behavior over time. This nding is consistent with the conceptualization of a balanced relationship system (Heider 1958). Moreover, our results are consistent with the prior empirical ndings suggesting that friends who share similar behavioral characteristics are more likely to foster continuity rather than change in behavior (Tremblay et al. 1995). Although additional research on the mutual attraction is warranted, it is equally important to note that based on the current ndings the unreciprocated peer nominations, often disregarded in research on peer relationships, seem to provide valuable information about unmet social needs and their power to change behavior. The focus of our investigation was to predict changes in negative rather than positive social behaviors during middle school years. Hence, it remains unclear whether the same mechanisms could help us explain changes in prosocial behaviors. Prior research shows that mutual friends prosocial behavior in sixth grade predicts target students prosocial behavior by eighth grade (Wentzel et al. 2004). The question is whether admiration of or unreciprocated attraction to peers who engage in kind rather than unkind behaviors also propel youth to engage in prosocial conduct. Prosocial peers may be more likely to accept a bid for afliation than those who engage in bullying. Hence, the mechanisms accounting for behavior changes over time may not be identical across pro- and antisocial conduct. Indeed, prior evidence suggests that there are age and gender differences in the types of behaviors that are most susceptible to peer inuence (Duncan et al. 2005; Hanish et al. 2005). In light of these ndings, we cannot presume that the processes tested in the current investigation are

applicable across a wide range of behaviors or developmental phases. Our conceptual orientation presumes a particular temporal order: perceiving someone possessing high social status, and a desire to afliate with a peer who does not reciprocate the desire, are likely to encourage youth to emulate their behavior. Yet our multi-wave longitudinal data do not allow us to make causal inferences and we cannot presume that antisocial behaviors do not affect the formation of relationships. It is therefore important to rely on experimental methodology that allows manipulation of social motives. Because much of the relevant experimental research comes from social psychological research on adults (e.g., Baumeister 1982; Leary and Kowalski 1990), one question is whether the same mechanisms are applicable to youth entering middle school. Based on crosssectional data, there is evidence suggesting that by the typical middle school entry age at 12, youth have learned that they can solicit social approval by behaving in ways that are consistent with the values of those they wish to afliate with or impress (Juvonen and Murdock 1995). Given that youth, like adults, presume that overt behaviors (e.g., antisocial behavior) reect the private values of the person, they might therefore engage in similarly negative social behaviors when wanting to seek their company or attention (Miller and Prentice 1994). Although we obtained support for two of our hypothesis, the effect sizes documented were very small for the sample as a whole. However, given the high stability of teacher ratings of antisocial conduct, and given that we also controlled for other known predictors (gender and ethnicity) of teacher rated behaviors, the small effects are understandable. We also limited the number of nominations thereby restricting the range of the predictor variables. Additionally, although we expected specic types of antisocial behaviors (i.e., bullying) to predict more general antisocial conduct (e.g., starting ghts, disruptiveness), peers are likely to be privy to particular bullying behaviors (e.g., spreading of rumors) beyond the radar screen of teachers. Hence, the fact that two of the tested motives explained any amount of variance over and above the other predictors, speaks to the robustness of our ndings. Finally, the lack of gender and ethnic differences in the associations between the presumed motives and behavior suggests that the documented affects apply to a diverse group of youth. Yet, in light of the urban and heavily (44%) Latino sample, it is important to try to replicate the current ndings across samples that vary in demographic composition. Our approach to understanding the motivational mechanisms underlying peer selection and socialization and changes in negative behaviors during middle school years differs from past approaches. For example, many studies focus specically on individual differences in initial levels

123

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

755 Hanish, L. D., Martin, C. L., Fabes, R. A., Leonard, S., & Herzog, M. (2005). Exposure to externalizing peer in early childhood: homophily and peer contagion processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 267281. Hartup, W. W. (2005). Peer interaction: What causes what? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 387394. Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley. Juvonen, J., & Galvan, A. (in press). Peer inuence in involuntary social groups: Lessons from research on bullying. In M. J. Prinstein, & K. A. Dodge, (Eds.), Peer inuence processes among children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press. Juvonen, J., Graham, S., & Schuster, M. (2003). Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics, 112, 12311237. Juvonen, J., & Murdock, T. B. (1995). Grade-level differences in the social value of effort: Implications for the self-presentation tactics of early adolescents. Child Development, 66, 16941705. Kandel, D. B. (1978). Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 427 436. Kellam, S, Ling, X., Merisca, R., Brown, C., & Ialongo, N. (1998). The effect of the level of aggression in the rst grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Development & Psychopathology, 10, 165185. La Fontana, K. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (1998). The nature of childrens stereotypes of popularity. Social Development, 7, 301320. La Fontana, K. M., & Cillessen, A. (2003). Childrens perceptions of popular and unpopular peers: A multimethod assessment. Developmental Psychology, 38, 63547. Lahey, B. B., Gordon, R. A., Loeber, R., Southamer-Loeber, M., & Farrington, D. P. (1999). Boys who join gangs: A prospective study of predictors of rst gang entry. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27, 261276. Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 3447. Miller, D. T., & Prentice, D. A. (1994). Collective errors and errors about the collective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 541550. Moftt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674701. Moynihan, M. (1968). Social mimicry: Character convergence versus character displacement. Evolution, 22, 315531. Mrug, S., Hoza, B., & Bukowski, W. M. (2004). Choosing or being chosen by aggressive-disruptive peers: Do they contribute to childrens externalizing and internalizing Problems? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 32, 5365. Parkhurst, J. T., & Hopmeyer, A., (1998). Sociometric popularity and peer-perceived popularity: Two distinct dimensions of peer status. Journal of Early Adolescence, 18, 125144. Poulin, F., Dishion, T. J., & Haas, E. (1999). The peer inuence paradox: Friendship quality and deviancy training within male adolescent friendships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 4261. Roeser, R. W., & Eccles, J. (1998). Adolescents perceptions of middle school: Relation to longitudinal changes in academic and psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8, 123158. Seidman, E., Allen, L., Aber, J. L., Mitchell, C., et al. (1994). The impact of school transitions in early adolescence on the self system and perceived social context of poor urban youth. Child Development. Special Issue: Children and Poverty, 65, 507 522.

of antisocial behavior because it is presumed that those who display high levels of problem behaviors are the ones who will most susceptible to negative peer inuence (e.g., Mrug et al. 2004). Other studies (e.g., Kellam et al. 1998) examine how contextual factors (e.g., classroom level aggression) amplify such individual differences. We believe that the examination of social motives offers yet another approach, inasmuch as questions about interpersonal attraction to particular peers and recognition of their high social status allows us to gain insight into the social meaning of behaviors to individual students.

Acknowledgments This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (BCS-9911525) and the William T. Grant Foundation (99100463) awarded to Sandra Graham and Jaana Juvonen. We thank Drs. Sandra Graham, Amy Bellmore, and Adrienne Nishina for their feedback on the earlier drafts of this article.

References

Baumeister, R. F. (1982). A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 326. Berndt, T. J., & Keefe, K. (1995). Friends inuence on adolescents adjustment to school. Child Development, 66, 13121329. Berndt, T. J., & Perry, T. B. (1986). Childrens perceptions of friendships and other supportive relationships. Developmental Psychology, 22, 640648. Cairns, R. B., & Cairns, B. D. (1994). Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Cairns, R. B., Leung, M. C., Gest, S., & Cairns, B. D. (1995). A brief method for assessing social development: structure, reliability, stability, and developmental validity of the interpersonal competence scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 725736. Cohen, G. L., & Prinstein, M. J. (2006). Peer contagion of aggression and health risk behavior among adolescent males: An experimental investigation of effects on public conduct and private attitudes. Child Development, 77, 967983. Dishion, T. J., Nelson, S. E., Winter, C. E., & Bullock, B. M. (2004). Adolescent friendship as a dynamic system: Entropy and deviance in the etiology and course of male antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 651663. Dishion, T. J., Spracklen, K. M., Andrews, D. W., & Patterson, G. R. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27, 373390. Duncan, G. J., Boisjoly, J., Kremer, M., Levy, D. M., & Eccles, J. (2005). Peer effects in drug use and sex among college students. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 375385. Gest, S. D., Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Hartup, W. W. (2001). Peer experience: Common and unique features of friendships, network centrality, and sociometric status. Social Development, 10, 2340. Granic, I., & Dishion T. J. (2003) Deviant talk in adolescent friendships: A step toward measuring a pathogenic attractor process. Social Development, 12, 314334. Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor. Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage-environment t during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 43, 522537.

123

756 Tremblay, R. E., Masse, L. C., Vitaro, F., & Dobkin, P. L. (1995). The impact of friends deviant behavior on early onset of delinquency: Longitudinal data from 6 to 13 years of age. Developmental and Psychopathology, 7, 649667. Warren, K., Schoppelrey, S., Moberg, D. P., & McDonald, M. (2005). A model of contagion through competition in the aggressive behaviors of elementary school students. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 283292. Wentzel, K. R., McNamara Barry, C., & Caldwell, K. A. (2004). Friendships in middle school: Inuence on motivation and school adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 195 203.

J Youth Adolescence (2008) 37:747756

Author Biographies

Jaana Juvonen, Ph.D. is a Professor and Chair of Developmental Psychology Program at University of California, Los Angeles. Her area of expertise is in young adolescent peer relationships and school adjustment. Alice Y. Ho, MA is a doctoral student in the Department of Education at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her major research interests include adolescent development, ethnic identity development and ethnic diversity, and academic achievement.

123

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Handbook of Mindfulness-Based Programmes Mindfulness Interventions From Education To Health and Therapy (Itai Ivtzan) (Z-Library)Document442 pagesHandbook of Mindfulness-Based Programmes Mindfulness Interventions From Education To Health and Therapy (Itai Ivtzan) (Z-Library)VItória AlbinoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Eastman 2021 Can Luxury Attitudes Impact SustainDocument14 pagesEastman 2021 Can Luxury Attitudes Impact SustainJuanjo CuencaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Relations Among Speech, Language, and Reading Disorders: Annual Review of Psychology January 2009Document28 pagesRelations Among Speech, Language, and Reading Disorders: Annual Review of Psychology January 2009bgmediavillaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Philosophy of Education ExplainedDocument7 pagesPhilosophy of Education Explainedshah jehanNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Assignment For Syllabi - Makingrevised 0415 - 2Document21 pagesAssignment For Syllabi - Makingrevised 0415 - 2Ryan Christian Tagal-BustilloNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Fs 5 - Episode 2Document4 pagesFs 5 - Episode 2api-334617470No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Advanced Clinical Teaching - For PrintingDocument20 pagesAdvanced Clinical Teaching - For PrintingKevin Roy Dela Cruz50% (2)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Remedios Elementary School MELCs GuideDocument10 pagesRemedios Elementary School MELCs GuideRames Ely GJNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Motivation in Learning English SpeakingDocument46 pagesMotivation in Learning English Speakinghoadinh203No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- SNR Englisch-3Document6 pagesSNR Englisch-3Geoff WhiteNo ratings yet

- Sado Masochism in Thelemic RitualDocument3 pagesSado Masochism in Thelemic RitualYuri M100% (2)

- The Role and Impact of Advertisement On Consumer Buying BehaviorDocument19 pagesThe Role and Impact of Advertisement On Consumer Buying Behaviorvikrant negi100% (11)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Decision Quality. The Fundamentals of Making Good DecisionsDocument24 pagesDecision Quality. The Fundamentals of Making Good DecisionsDorin MiclausNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Bread and Pastry Production NC IiDocument4 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Bread and Pastry Production NC IiMark John Bechayda CasilagNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- 7 Qualities of LeadershipDocument7 pages7 Qualities of LeadershipOmkar SutarNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Stress Management Study at Meenakshi HospitalDocument83 pagesStress Management Study at Meenakshi HospitalVignesh S100% (1)

- Assignment On OB ASDA and BADocument12 pagesAssignment On OB ASDA and BAshovanhr100% (2)

- Consumer behaviour towards smartphones in Indian marketDocument99 pagesConsumer behaviour towards smartphones in Indian marketEdwin LakraNo ratings yet

- Different Types of CommunicationDocument79 pagesDifferent Types of CommunicationMark225userNo ratings yet

- A Review On Peer Correction: Writing 5Document4 pagesA Review On Peer Correction: Writing 5dphvuNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Discipline Problems in SchoolDocument5 pagesDiscipline Problems in SchoolSusanMicky0% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Leadership Book HandoutDocument3 pagesLeadership Book Handoutapi-516897718No ratings yet

- Philippine Court Hearing on Declaration of Nullity of MarriageDocument8 pagesPhilippine Court Hearing on Declaration of Nullity of MarriageFrederick Barcelon60% (5)

- Effects of Bullying on Academic PerformanceDocument11 pagesEffects of Bullying on Academic Performanceedward john calub llNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Behavioral Health ProfessionalsDocument5 pagesBehavioral Health ProfessionalsNoelle RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Learning Skills 1234Document19 pagesLearning Skills 1234ninakarenNo ratings yet

- Social-Behavioristic Perspective: B.F.Skinner: PN - Azlina 1Document9 pagesSocial-Behavioristic Perspective: B.F.Skinner: PN - Azlina 1farahNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLesson Planapi-261245238No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Do Avatars Dream About Virtual Sleep?: Group 1Document13 pagesDo Avatars Dream About Virtual Sleep?: Group 1Kim NgânNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Task Based Approach and Traditional Approach in English Language TeachingDocument18 pagesA Comparative Study of Task Based Approach and Traditional Approach in English Language TeachingSYEDA ZAHIDA RIZVINo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)