Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sharia Punishment Treatment and Speaking Out

Uploaded by

Leah MclellanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sharia Punishment Treatment and Speaking Out

Uploaded by

Leah MclellanCopyright:

Available Formats

BMJ 1999;319:445-447 ( 14 August )

Sharia punishment, treatment, and speaking out

Humanitarian aid organisations may face situations which challenge their guiding ethics and principles. Amputations after convictions under sharia law, in countries such as Afghanistan, have posed just such a problem. Should the aid organisation continue to provide health care, including treatment to the person who had been punished, or would this make it complicit in a practice that it sees as contrary to human rights? The conclusions and the actions taken by the International Committee of the Red Cross and Mdecins Sans Frontires differ, as outlined in these two accounts. But the ethical bases of their positions are remarkably similar. Pierre Perrin, chief medical officer.

International Committee of the Red Cross, 19 Avenue de la Paix, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland

In 1997 an Afghan surgeon who was being paid by the International Committee of the Red Cross but who was working in a Ministry of Health hospital was taken by the local authorities to a marketplace. There he amputated the hand of a person who had been convicted under sharia law. Following an appeal by the international committee to the Taliban authorities, an agreement was eventually reached that ensured that neither hospitals assisted materially by the international committee nor staff paid by it would be involved in this practice. Subsequent requests made by the authorities to the assisted hospitals to provide an ambulance or surgical instruments to perform public amputations were refused. Many of the international committee's personnel working with and training Afghan staff were health professionals from Western countries and they faced a dilemma in treating people brought to hospital after having suffered an amputation under sharia. Did treating these victims constitute offering support to a process of torture or cruel and degrading treatment, or was it treating a patient in need of urgent surgical care?

Examination of relevant laws and standards of medical ethics

These dilemmas forced the International Committee of the Red Cross to examine its position on corporal punishment, its field operations, the relevant international humanitarian and human rights laws, and standards of medical ethics; it forced the international committee to adopt a firm position with regard to the government in the relevant country; and it also forced the international committee to draw up guidelines for its health professionals working in Afghanistan or any other country where sharia is enforced.

The international committee decided in 1988 not to make a statement on whether corporal punishment constituted torture and not to comment on cultural or religious issues. Nevertheless, the international committee did state that in a situation of armed conflict (the context in which it works most frequently), such punishment constituted a grave breach of international humanitarian law. As a result of the incident in 1997, the international committee re-examined this position, keeping the specific situation of Afghanistan in mind. Although article 3, common to the Geneva Conventions, expressly forbids mutilation, cruel treatment, and torture, it is difficult to say whether a person who is convicted of being a criminal in present day Afghanistan is protected by this article. Various tenets of human rights law obviously apply; however, arguments against amputations performed under sharia which use human rights as a basis are unlikely to succeed in Afghanistan because they may be in conflict with locally enforced law (sharia). In Afghanistan, it is important that the international committee is not perceived as promoting Western values or as antagonistic to Islam. The presence and security of its personnel in the country might be put at risk. Thus, the international committee appeals directly to the authorities for leniency in cases in which those who are convicted may not be protected by international humanitarian law. Both protocol II, additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, which applies to non-international armed conflict, and the 1982 resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations1 clearly state that whether in armed conflict or in general, the participation by a health professional in corporal punishment constitutes a grave breach of the ethical codes of the medical profession. The declaration made in Tokyo by the World Medical Association in 1975 (adopted by the 29th World Medical Assembly) is more specific and states that a doctor must never participate in any such act in any situation; must never provide the place, means, knowledge, or materials to facilitate such an act; and must never be present during such an act. The 1997 declaration made by the World Medical Association in Hamburg (adopted by the 49th World Medical Assembly) was aimed at uniting the profession to support doctors who refuse to participate in, or to condone, the use of torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. In addition to these ethical guidelines, the World Medical Association has stated in a number of declarations that all patients have the right to receive appropriate medical care without discrimination. Although a doctor has a right to choose which patients to treat, it is clear that "physicians have a compelling professional and ethical duty to attend to a patient in an emergency." The International Conference on Islamic Medicine in Kuwait in 1981 stated: "Health is a basic human necessity and is not a matter of luxury. It follows that the medical profession is unique in that the client is not denied the service even if he cannot afford the fee." With respect to a doctor's practice, the conference stated that: "He should be an instrument of God's mercy not of God's

justice, forgiveness and not punishment, coverage and not exposure." The conference also stated: "The medical profession shall not permit its technical, scientific, or other resources to be utilised in any sort of harm or destruction or infliction upon man of physical, psychological, moral, or other damage ... regardless of all political or military considerations."

Guidelines for action

The first Geneva Convention clearly gives anyone wounded in armed conflict the right to treatment; this is the reason for the existence of the International Committee of the Red Cross' surgical teams. However, in the case of sharia amputations, the international committee recognises that the ethics of an individual doctor working for the organisation might be in conflict with both the ethics of the medical profession and the ethics of the international committee. Every measure is taken to avoid such a conflict occurring. This means that health professionals recruited for such work are informed of the possibility that this situation might arise before they are sent overseas. They are not accepted for the mission if they disagree with established professional or institutional ethics. The International Committee of the Red Cross has not changed its position on corporal punishment. However, in the case of amputations carried out under sharia, the international committee has decided that it will take action. The international committee will: State its objection to amputations based on sharia law but will not do so publicly Refuse to allow personnel employed by the international committee to participate in performing amputations under sharia Refuse to provide the premises, the knowledge, or material for performing these amputations Call for leniency in each case Protect doctors who refuse to participate in sharia amputations Support the World Medical Association in working to develop national legislation against such practices, and Support the World Medical Association in its efforts to develop national medical associations to provide support for doctors who refuse to carry out sharia sentences.

The International Committee of the Red Cross informs all health professionals

of its position on these issues. The international committee will treat all people who have had amputations as a result of sharia. It will remind all doctors that they have a duty to treat them. And it will inform the doctors who treat them that they have the support of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

References

1. United Nations. Principles of medical ethics relevant to the role of health personnel, particularly physicians, in the protection of prisoners and detainees against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. New York: United Nations , 1994(A/RES/37/94.)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Christianity and Islam: Two Worldviews and Why They MatterDocument3 pagesChristianity and Islam: Two Worldviews and Why They MatterLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Us MarriagesDocument6 pagesUs MarriagesLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Same Sex ParentingDocument7 pagesSame Sex ParentingLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Jihad Vs - Rel - LibertyDocument1 pageJihad Vs - Rel - LibertyLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Nag Hammadi GospelsDocument3 pagesNag Hammadi GospelsLeah Mclellan0% (1)

- Jesus Vs - MuhammedDocument1 pageJesus Vs - MuhammedLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- News You Didn't Hear From Tom BrokawDocument7 pagesNews You Didn't Hear From Tom BrokawLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- BR 9329Document5 pagesBR 9329Leah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Honor Killing" Is Absolutely Islamic!: Syed Kamran MirzaDocument11 pagesHonor Killing" Is Absolutely Islamic!: Syed Kamran MirzaLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- One Nation, Under GodDocument2 pagesOne Nation, Under GodLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- What Do Leading Authorities Say About When Life BeginsDocument6 pagesWhat Do Leading Authorities Say About When Life BeginsLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- The Trinity-Part 4Document2 pagesThe Trinity-Part 4Leah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Christianity Vs IslamDocument3 pagesChristianity Vs Islammmcelhaney0% (1)

- Jesus Vs - MuhammedDocument1 pageJesus Vs - MuhammedLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Is Allah Just Another Name For The God of The BibleDocument1 pageIs Allah Just Another Name For The God of The BibleLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Islam Vs - GraceDocument1 pageIslam Vs - GraceLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- How Do Muslims View Jesus ChristDocument2 pagesHow Do Muslims View Jesus ChristLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Islam Vs - GraceDocument1 pageIslam Vs - GraceLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Abu Atallah - Answers For Muslims - Has The Bible Been Corrupted PDFDocument2 pagesAbu Atallah - Answers For Muslims - Has The Bible Been Corrupted PDFmsdfli0% (1)

- Glossary of Arabic TermsDocument5 pagesGlossary of Arabic TermsLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Outstretched HandDocument1 pageOutstretched HandLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Christianity Vs IslamDocument3 pagesChristianity Vs Islammmcelhaney0% (1)

- Right WomanDocument22 pagesRight WomanLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Are Allah and The Biblical God The SameDocument2 pagesAre Allah and The Biblical God The SameLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Bride and GroomDocument1 pageBride and GroomLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- FlirtingDocument8 pagesFlirtingLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- The BoxDocument1 pageThe BoxLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- The Right StuffDocument11 pagesThe Right StuffLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- An Unpopular Message: Pre-Marital Sex and The Biblical Obligations of MenDocument13 pagesAn Unpopular Message: Pre-Marital Sex and The Biblical Obligations of MenLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- Hurt in Flirt inDocument9 pagesHurt in Flirt inLeah MclellanNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- (Grade Code 6404) : Louise - Collins4@hse - IeDocument7 pages(Grade Code 6404) : Louise - Collins4@hse - IeeimearNo ratings yet

- Childhood Emotional Disorders: Treatments and Interventions for NursesDocument28 pagesChildhood Emotional Disorders: Treatments and Interventions for NursesjoycechicagoNo ratings yet

- FINAL History of Psychiatric ClassificationDocument89 pagesFINAL History of Psychiatric ClassificationAli B. SafadiNo ratings yet

- The Nursing ProfessionDocument22 pagesThe Nursing ProfessiongopscharanNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Disorder and Alcoholism: Susan C. Sonne, Pharmd, and Kathleen T. Brady, M.D., PH.DDocument6 pagesBipolar Disorder and Alcoholism: Susan C. Sonne, Pharmd, and Kathleen T. Brady, M.D., PH.DFrisca Howard Delius CharlenNo ratings yet

- Delirium, Dementia, PsychosisDocument2 pagesDelirium, Dementia, PsychosisLagente EstalocaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Violations and Board DisciplineDocument4 pagesEthical Violations and Board DisciplineRotich KorirNo ratings yet

- INDIAN LEGAL PERSPECTIVE ON MEDICAL NEGLIGENCEDocument15 pagesINDIAN LEGAL PERSPECTIVE ON MEDICAL NEGLIGENCEGitanshu SamantarayNo ratings yet

- Clinical Ethics For The Treatment of Children and AdolescentsDocument15 pagesClinical Ethics For The Treatment of Children and AdolescentsPierre AA100% (1)

- Music Therapy and Eating DisordersDocument21 pagesMusic Therapy and Eating DisordersChristie McKernanNo ratings yet

- Informed Consent JournalDocument8 pagesInformed Consent JournalRhawnie B. GibbsNo ratings yet

- How To Speak Up For LifeDocument12 pagesHow To Speak Up For LifeThe Heritage Foundation100% (4)

- Cornerstone CEU Descriptions HoustonDocument3 pagesCornerstone CEU Descriptions HoustonRenzo BenvenutoNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia and SuicideDocument27 pagesEuthanasia and SuicideJa DimasNo ratings yet

- Fetish Is MeDocument7 pagesFetish Is MeErna YuliantiNo ratings yet

- ECT AssignmentDocument27 pagesECT AssignmentJennifer Dixon100% (1)

- Psychiatric Sample QuizDocument4 pagesPsychiatric Sample QuizAriesChanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 022Document9 pagesChapter 022api-281340024100% (2)

- Bioethics and Professionalism in Medical - MK EthumDocument49 pagesBioethics and Professionalism in Medical - MK EthumKhanza malahaNo ratings yet

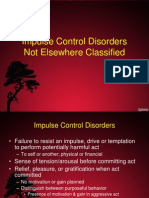

- Impulse Control DisordersDocument97 pagesImpulse Control DisordersGanpat VankarNo ratings yet

- OCD Facts: Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentsDocument2 pagesOCD Facts: Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentsyoyoyoNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates: Region Xiii Agusan Del Sur Provincial GovernorDocument21 pagesCertified List of Candidates: Region Xiii Agusan Del Sur Provincial GovernorDrakeNo ratings yet

- O&G SyllabusDocument8 pagesO&G SyllabusHo Yong WaiNo ratings yet

- Belize Rural North PDFDocument99 pagesBelize Rural North PDFSeinsu ManNo ratings yet

- DelusionsDocument8 pagesDelusionsvenkyreddy97No ratings yet

- Timeline of Abortion Laws in TexasDocument1 pageTimeline of Abortion Laws in TexasProgressTX100% (1)

- CRAFFT English PDFDocument2 pagesCRAFFT English PDFYudha KhusniaNo ratings yet

- Mental Disorders-A MindHeal Homeopathy CaseStudyDocument2 pagesMental Disorders-A MindHeal Homeopathy CaseStudyDr. Anita SalunkheNo ratings yet

- Oriental Mindoro voters list by precinctDocument32 pagesOriental Mindoro voters list by precinctAngelika CalingasanNo ratings yet

- Difficult Parent Questionnaire: E. Self-Destructive BehaviorsDocument1 pageDifficult Parent Questionnaire: E. Self-Destructive BehaviorsAbo Ahmed TarekNo ratings yet