Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Joshua Rovner and Austin Long - Intelligence Failure and Reform: Evaluating The 9/11 Commission Report

Uploaded by

AlarmakOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Joshua Rovner and Austin Long - Intelligence Failure and Reform: Evaluating The 9/11 Commission Report

Uploaded by

AlarmakCopyright:

Available Formats

Intelligence Failure and Reform: Evaluating the 9/11 Commission Report Joshua Rovner and Austin Long The

9/11 Commission report has been uniquely influential in the debate about the organization of intelligence in the United States. Many of its recommendations were incorporated into the recently passed legislation that will enact the most sweeping changes to the intelligence community since 1947. In this paper, we examine the theories of intelligence failure presented by the Commission, and assess how closely the proposed reforms are linked to those theories. We make two principal arguments. First, the theories of failure are underdeveloped at best. Second, the proposed reforms are mostly unrelated to the postulated causes of failure. For these reasons, the large organizational reforms currently underway are unlikely to significantly improve intelligence performance. We conclude by offering a few practical alternatives.

Imagination The 9/11 Commission found that the intelligence community suffered from a lack of institutional imagination before the September 11 attacks. This made it impossible for most analysts and policymakers to accurately gauge the terrorist threat. Had they better understood the danger of al Qaeda they could have taken steps to improve warning intelligence. More imagination also might have helped analysts reveal the crucial network of terrorists that planned and executed the attacks. In other words, the intelligence community could not connect the dots because it was not sufficiently imaginative. 1 Finally, according to the Commission, more imagination could have stimulated more aggressive counter-terror policies and more vigilant homeland security. Halting efforts to combat terrorists abroad during the Clinton and Bush administrations suggest that they never fully understood the threat. In terms of homeland security, wider distribution of CIA threat reporting on terrorist operatives might have brought much more attention to the need for permanent changes in domestic airport and airline security procedures. 2 Although some agencies were concerned about a possible hijacking before

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

September 11, they did not undertake standard procedures developed over the years to guard against a surprise attack. Specifically, they did not analyze how terrorists might use an aircraft as a weapon, or describe the telltale indicators that would have revealed planning for such an operation. The intelligence community did not, for instance, assign analytical teams to play the role of terrorists. These red teams might have stimulated creative thinking and alerted the community to the nature of the threat. 3 Surprisingly, the Commission did not explicitly link any of its proposals to this theory of failure, despite the emphasis on imagination in the Commissions explanation of what went wrong. Chapter 8 of the report goes into great detail about how the intelligence community did not fully understand the warning signs, even though the system was blinking red with them in the summer of 2001. Chapter 11 describes the many missed opportunities to disrupt al Qaeda operations. The community had critical information at is disposal, but it could not sense the importance of what it was seeing. Still, none of the 9/11 Commission proposals offer clear suggestions about how to institutionalize imagination. It never says which proposals are supposed to help the intelligence community foresee threats to national security. Five proposals, however, are indirectly related to the issue. National Intelligence Centers. The Commission proposed the creation of an expanded National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) as well number of smaller issuespecific analytic centers. This recommendation was included as part of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004. Modeled after the militarys combatant commands, these national intelligence centers would focus on specific issues and regions. The primary purpose of the centers would be to help policymakers coordinate information by pooling intelligence and streamlining information channels. They would also help institutionalize imagination, because dedicated centers would allow analysts to probe more deeply into specific issues. The NCTC would build upon the existing Terrorist Threat Integration Center (TTIC), increasing the number of analysts working on the problem. Presumably, analysts would enjoy more time to implement the threat assessment and warning techniques that were neglected before September 11. This logic is hard to follow. The Commission observed, Imagination is not a gift usually associated with bureaucracies, yet it recommended enlarging the bureaucracy by

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

substantially expanding TTIC. 4 This is not consistent with a theory of failure based on imagination, because adding analysts does not ensure analytical creativity. Without rigorous hiring procedures and improved professional training programs, an increase in the size of the counterterrorism center may lower the quality of its work. In the 1990s, by comparison, the workforce at the CIAs Directorate of Intelligence was reduced by 22%. Near the end of the decade, DI chiefs came to the radical admission that their work needed to become more rigorous and relevant to policymakers. 5 They created the Career Analyst Program to train new employees, the Sherman Kent Center for Intelligence Analysis, and the Senior Analyst Service to retain top analysts at higher pay grades without having to move them to management roles. 6 In short, the reduction in the size of the bureaucracy forced a reconsideration of its methods. A large unstructured increase in NCTC resources will remove its incentive to do likewise. To be clear, we are not in principal opposed to adding intelligence resources to the counterterrorism effort. But any increase must be accompanied by complimentary professional training initiatives and incentive-laden retention programs. Another problem is that agency managers have little incentive to send their best analysts to the new intelligence centers. The Commission approves of the GoldwaterNichols legislation of 1986, which required military officers to serve joint tours in order to win promotion. 7 We assume that the Commission supported such an arrangement for staffing decisions with respect to the national intelligence centers. Indeed, the final reform bill gives the DNI the authority to offer incentives for service in his staff, the NCTC, or any of the centers. 8 This is certainly a good idea, but managers will still be reluctant to part with their best and brightest. The problem is compounded by the Commissions recommendation that the director of NCTC perform personnel evaluations. In theory he could monitor the performance of his staff and blow the whistle on agency managers for assigning sub par analysts to the center. But the perils of organizational self-evaluation are well known; honest assessment is unlikely because it threatens the status of the existing hierarchy. 9 The upshot of all this is that agency managers will send lesser analysts to the NCTC, and the NCTC will be inclined to overrate their performance. It remains to be seen whether the financial and career incentives for joint intelligence tours will be enough to overcome

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

these problems. If not, then the creation of national intelligence centers will do little to institutionalize imagination. The Commission also argued that the centers would present a straightforward way for policymakers to receive alternative analyses. By providing a benchmark for issuespecific intelligence, the Commission hopes that the White House will learn to balance the advice of these intelligence chiefs against the contrasting viewpoints that may be offered by department heads at State, Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, and other agencies. 10 This hopeful outcome, however, is predicated on an unrealistic faith in policymakers. It assumes that they will conduct a thorough and objective review of competing views, rather than rely on analyses that support preferred policy positions. Policymakers suffer the same psychological biases as anyone else; they develop worldviews that frame how they perceive world events, and lean toward analyses that support their own predispositions. 11 Moreover, policymakers are subjective consumers of intelligence, with strong political incentives to disregard unsettling estimates. Unsurprisingly, leaders have a long history of ignoring such intelligence. 12 In any case, leaders already have the opportunity to weigh competing analyses from the intelligence community and request specific products. Unsatisfied policymakers can even create ad hoc bodies to review intelligence and explore alternative hypotheses. (This was the purpose of the Office of Special Plans, the Pentagon working group that challenged existing estimates on Iraq and al Qaeda before the war.) If the 9/11 Commission was truly interested in fostering imagination, it made little sense to propose consolidating intelligence in national intelligence centers. Such consolidation is likely to decrease the number of competing analyses that make it to the White House. Director of National Intelligence. 13 The second proposal to improve imagination relates to the creation of a director of national intelligence. The Commission argued that DNI would allow the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) to focus on rebuilding analytic capabilities in the CIA. The DCI has traditionally served as the head of CIA, the principal intelligence advisor to the president, and the nominal leader of the entire intelligence community. By stripping the DCI of his advisory and coordinating duties, the Commission concluded that he could concentrate on improving CIA analyses. 14

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

While this sounds reasonable, the Commission is vague about how this will actually take place. One section of the report encourages the DCI to increase diversity at CIA. This makes some sense in terms of institutionalizing imagination, because analysts with diverse backgrounds bring different language skills and perspectives to the job. But it also raises important questions. When the Agency is making hiring decisions, for example, will diversity trump analytical skill? If so, then analysis may become unfocused or misguided. The Commission assumes that diversity is a good in itself. This may be true, but there is no supporting discussion in the report. 15 The congressional reform bill is unclear about the future role of the DCI. Breaking from the 9/11 Commission, it places primary responsibility for institutionalizing imagination with the DNI. 16 The legislation also includes provisions that direct the DNI to ensure high-quality analytic methods and protect the objectivity of analysis. 17 But the real authority of the DNI is ambiguous. Although given broad nominal control over budgets, personnel, and tasking, there is no guarantee that the DNI will have the bureaucratic influence to impose his will over the community, especially because the reform bill states that the DNI cannot abrogate the statutory responsibilities of the Secretary of Defense. 18 Meanwhile, the DCI will fight to retain control over the CIA after being stripped of other responsibilities. Under these conditions, it is hard to imagine how the DNI will be able to force the community to become more imaginative. Declassifying the intelligence budget. The Commission recommended declassifying intelligence spending, which is currently hidden in the defense budget. It correctly argues that no informed public debate over priorities can occur as long as the public is kept unaware of the total spending and basic distribution of funds in the intelligence community. This proposal is both sensible and long overdue. Unfortunately, Congress did not include it in the final reform package. 19 FBI intelligence. The Commission recommended building a special national security workforce within the FBI. The Bureaus traditional focus has been criminal justice, which the Commission notes is a wholly different discipline from national security. As a law enforcement agency, its evidentiary standards are far higher than those of intelligence agencies that work abroad. Intelligence agencies need only provide

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

reasonably actionable intelligence for policymakers; law enforcement must provide evidence that can stand up in a court of law. The legal and doctrinal gap between the FBI and national intelligence agencies inhibits cooperation within the intelligence community, and the proposal to bolster the FBIs intelligence apparatus is primarily concerned with improving coordination. 20 But it may also improve imagination by adding analysts with domestic intelligence experience. This recommendation is sound, even though it is only tangential to the theory of insufficient imagination. Congress acted on the proposal by expanding the renamed FBI Directorate of Intelligence to include both oversight of FBI field operations and strategic analysis. 21 Threat and readiness assessments. Finally, the Commission recommended that the Departments of Homeland Security and Defense conduct regular threat and readiness assessments. 22 It criticized North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) for ignoring the threat posed by planes taking off from domestic runways before September 11. This was implicitly a failure of imagination, and regular DOD threat assessments will take steps to avoid tunnel vision in the future. The DHS readiness checks serve a similar purpose, even though they are geared mainly towards improving the efficiency and reliability of first responders. Both of these proposals were incorporated into the congressional reform bill. 23 Summary. There is a significant gap between the Commissions theory of insufficient imagination and its proposed solutions. It is unlikely that any of the major changes will help generate analytical imagination. The creation of national intelligence centers is a costly enterprise that rests on unrealistic faith in policymakers objectivity. The call for a larger and more diverse community of analysts may perversely drive down the quality of its work. And there is no reason to expect that the DCI will be more able to stimulate imagination after he is stripped of his title as principal intelligence advisor. More sensible proposals in the Commission report are only peripheral to the imagination problem. These include expanding the FBIs intelligence capabilities and mandating regular DOD and DHS threat and readiness assessments. These plans build upon existing resources and should offer some gain. One recommendation, declassifying the intelligence budget, was both logical and clearly relevant to the theory of failure. Ironically, this was the proposal Congress chose to reject.

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

Management and Coordination The 9/11 Commission detailed a second theory of intelligence failure, failure of management, or more precisely, failure of coordination. The Commission's report notes information was not shared, sometimes inadvertently or because of legal misunderstandings. Analysis was not pooled. Effective operations were not launched. 24 The report goes on to make an analogy of the intelligence community as a hospital full of specialists with no attending physician to ensure unity of effort. The intelligence community was therefore unable to connect the dots not only due to a failure of imagination but a failure of coordination. If only Agency X had known what Agency Y knew, they could have done more or better. The report labels this a failure of operational management with the primary example used being the relationship of the National Security Agency (NSA), CIA and FBI regarding the entry of 9/11 hijackers Mihdhar and Hazmi into the United States. 25 In addition to failures of operational management, the 9/11 Commission identifies failures of institutional management. In contrast to operational management, which deals with day-to-day issues of coordination and tactics, institutional management is strategic. The Commission defines institutional management as dealing with the broader management issues pertaining to how the top leaders of the government set priorities and allocate resources. 26 The primary example given is the failure of a 1998 memo from DCI George Tenet declaring that the U.S. intelligence community was at war with terrorists to generate a substantial reprioritization of resources. 27 The Commission further argues that the DCI did not generate a management strategy for a war against Islamist terrorism before 9/11. 28 Two of the Commission's specific recommendations related to failures of management are worth addressing in detail. Creation of a Trusted Information Network/Shared Information Environment. The Commission report recommends that the President lead an effort to create a decentralized network that would allow all national security agencies to access one another's databases. This network would be highly secure and allow some retention of information rights by specific agencies, but its overall purpose would be to break down

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

barriers between agencies. In theory, this would allow the intelligence community to utilize the benefits of the information revolution to prevent failures of operational coordination, such as the NSA/CIA/FBI problem with Mihdhar and Hazmi. This recommendation is problematic for at least two reasons. First, it mirrors the argument of revolution in military affairs supporters in the defense community that networks of sensors can lift the fog of war, to use Vice Admiral Bill Owenss term. 29 This belief that information technology can remove most if not all of the uncertainty from warfare has been dealt a serious blow by the conflict in Iraq. Despite a major investment in information technology by the Defense Department, the fog of war was not lifted even during the relatively straightforward period of major combat operations culminating in the fall of Baghdad. This technology has also proved unable to deal with the ongoing insurgency in Iraq as well. 30 The problem of uncertainty in an environment in which a responsive adversary is actively attempting deception cannot be dispelled by information technology, either for the military or the intelligence community. Second, apart from the inherent uncertainty of military and intelligence activity, total sharing of information can lead to a very real danger of data overload. This data deluge is compounded by the often fragmentary nature of intelligence reporting, as it may be unclear whether an al-Hazmi intercepted talking to Osama Bin Laden on a cell phone is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's friend Nawaf or a different individual entirely. The foregoing is not to argue that information technology and data sharing are inherently bad, but should instead be viewed with at least a healthy skepticism. Many of the problems of coordination between agencies can be (and in some cases already have been) overcome by the simpler expedient of analysts cultivating relationships with colleagues in the community. An analyst at CIA who forms a relationship with colleagues at NSA will receive more than just data, they will also benefit from the colleague's expertise, experience and opinion. Convincing individual analysts to take the initiative to form relationships with colleagues is both less sexy and more difficult to mandate than the congressional intelligence reform bill's Information Sharing Environment. 31 However, it is both cheaper and more likely to produce long-term benefits.

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

The Director of National Intelligence. While the DNI has been discussed in the previous section on imagination, it is in the realm of management/coordination that the DNI is supposed to have the largest impact. Having one individual to oversee all budgets, coordinate action, and if necessary force compliance seems like an ideal solution to fractious infighting between government agencies. Yet the history of the United States government is littered with coordinators and czars who have made little difference, the drug czar of the Office of National Drug Control Policy and the Director of Central Intelligence being two among many. The difference with a DNI, supporters argue, is that he will have budgetary and personnel authority, enabling him to reward compliance and punish non-compliance. Even ignoring the previously noted limitations on the DNIs authority with regard to other cabinet officials, there is little reason to think that mere centralization and budget authority can tame unruly agencies. 32 Again, the forgoing is not to argue that attempting centralization or improving jointness are inherently bad ideas. Instead, the point is to highlight the enduring nature of interagency disputes and indicate that a quick fix though centralization is unlikely at best. Further, centralization is not without consequence, as discussed in more detail below.

Shallow Theories The 9/11 Commission Report is problematic on its own terms because of the conspicuous gap between its posited theories of failure and the recommended reforms. But there are also serious problems with the theories themselves. Both are badly underdeveloped, neglecting most of the literature on warning intelligence and strategic surprise. Thus it is no surprise that many of the Commissions recommendations are not logical solutions for improving intelligence. The theory of insufficient imagination is especially vague. It seems to refer only to the ability to anticipate spectacular attacks by transnational terrorist organizations. But individuals and intelligence agencies can imagine any number of possible scenarios. 33 In this light, it becomes clear that the 9/11 Commission left important questions unasked: Is there such a thing as too much imagination? How much is enough? And how can we

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

evaluate institutional imagination before something actually happens? In other words, how can the intelligence community ensure that it is being appropriately imaginative? Imagination comes at a cost, because unchecked scenario building gets in the way of setting priorities. In the 1990s, defense analysts criticized how concepts like capability-based planning justified military investment wholly disproportionate to genuine threats. Freed from what James Winnefeld called the tyranny of scenario plausibility, the Pentagon could spend lavishly on new technologies without regard to their real utility. Today it is trying to reign in these costs, partly because it has to pay for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. 34 The intelligence community needs to set priorities for the same reason. It cannot entertain all possibilities without diverting its attention from more realistic threats. Intelligence critics commonly decry the effects of psychological mindsets, which blind analysts to alternative possibilities. 35 But without the benefit of hindsight, it is very difficult to distinguish a mind-set from a rational appreciation of existing data. Indeed, analysts would be irresponsible if they failed to focus on the most likely risks. The 9/11 Commission report does not explore the fuzzy line between analytical tunnel vision and a healthy evaluation of the best available information. 36 The two variants on the theory of managerial failure are also flawed. The theory of failure resulting from poor operational management is not without some merit. Many of the agencies comprising the intelligence community have not historically interacted well. The derogatory rendering of the acronym DIA as Da Idiot Agency, has been used at CIA's Langley campus, while DIA analysts at Fort Belvoir respond with Clowns In Action. 37 Even within the CIA a cultural divide exists between the spies of the Directorate of Operations and the analysts of the Directorate of Intelligence. 38 However, to make the argument that poor centralization was the cause of 9/11 requires a number of what-ifs. Taking the Commission's main example, suppose perfect coordination existed and Hazmi and Mihdhar had been watchlisted. Would this have stopped 9/11? The Commission's report acknowledges that watchlisting alone was unlikely to have stopped the attack. 39 So it is unclear whether this failure materially resulted in the outcomes of 9/11.

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

10

Further, the argument that NSA should have done more to research the identities of Hazmi and Mihdhar without being asked shows a misunderstanding of the role of specific agencies in the community. Agencies like the NSA, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), and the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) are primarily producers of raw intelligence from national technical means. They are extremely proficient at their primary functions, but have relatively small, highly specialized analytic components. When the Commission argues that NSA saw itself as an agency to support intelligence consumers, it seems to indicate that NSA was mistaken in this belief. 40 In fact, this is exactly the role given to the NSA in Executive Order 12333, which defines the NSA's role as the collection, processing, and dissemination of signals intelligence in accordance with direction from the DCI. 41 In other words, NSA collects what other agencies task it to collect. Otherwise, the potentially infinite realm of signals to intercept or images to acquire would rapidly overwhelm the NSA or any of the other technical agencies. The second managerial theory, weak institutional management, is more tenuous than the first. The primary reason that DCI Tenet's memo had little impact is that, for obvious reasons, the DCI does not have the power to declare war. When the memo was issued, the Clinton Administration had spent much of the previous six years ignoring the intelligence community and was distracted by domestic scandal and other crises abroad. Even after the embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, the administration only launched a desultory military response. In light of this obvious ambivalence about terrorism in the Oval Office, it mattered little what DCI Tenet or any other official stated. Congress was equally uninterested. 42 The failure to develop a strategy for war with Islamic terror before 9/11 must be shouldered primarily by policymakers. It is not the role of the intelligence community to create national strategy. Instead, intelligence agencies, like the military, are advisors on and implementers of national strategy. 43

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

11

Conflicting Reforms The 9/11 Commission report assumes that imagination and coordination are symbiotic. Coordination, it argues, is only possible when analysts can accurately foresee the nature of future threats. With sufficient imagination, analysts can efficiently search through an avalanche of data to untangle the important signal from the background noise. Others have made the related point that consulting outside experts will help the community recognize previously hidden patterns. To protect the US, argue Gregory Treverton and Peter Wilson, every agency controls its own information, with access granted on a need to know basis. Yet creativity in analysis will come precisely from having people with no need to know look at data, because they may see patterns that current experts do not. 44 But what if the opposite is also true? What if efforts to increase institutional imagination end up conflicting with efforts to increase coordination? The Commission did not consider the possibility that its two core recommendations are at odds. A more comprehensive theoretical treatment would have at least addressed the latent tension between imagination and coordination. Imagination involves unconventional thinking; it means paying heed to alternative analyses and developing working scenarios from speculation. Coordination, on the other hand, involves getting analysts to focus on the same threats and scenarios. Here creativity gets in the way of the Commissions call for a unity of effort. For example, consider the tension between seeking a decentralized approach to operational management (in the form of the Information Sharing Environment and institutionalized alternative analysis) and a centralized approach to institutional management under the DNI. Centralized priorities and budgets may help the community effectively mine the data for relevant patterns. On the other hand, centralization may also lead to increased levels of consensus-seeking in the intelligence community, with all the perils of least common denominator analysis and groupthink. We suspect that the Commission overlooks these tradeoffs because it conflates coordination with data sharing, lumping them together under the rubric of management. Data sharing means making information more accessible to a wider number of analysts. Coordination means directing analysts, collectors, and operators to focus on the same issue. The Commission implicitly assumes that making information more transparent will lead to coordination

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

12

because important patterns will be revealed. 45 But there is no reason that this will automatically occur; experts often come to very different conclusions even when data is completely unrestricted. 46 What does this mean in terms of the recently passed intelligence bill? One consequence is that reforms cannot simultaneously improve institutional imagination as well as coordination. If they enhance coordination, the community will become less imaginative. More likely, however, is that the sweeping organizational changes will not do much for either problem. This is because in each case, the reforms are logically disconnected from the theorized causes of failure. Without specifically tying them to convincing theories, the reforms are nothing more than an expensive and time-consuming bureaucratic reshuffle.

Practical Recommendations This is not to say that the intelligence community cannot improve its performance by implementing more practical recommendations. Such reforms will probably never be front-page news, but they may have a positive and lasting effect on community performance. The 9/11 Commission included some of these ideas in its report. Declassifying the top line intelligence budget and standardizing clearance procedures, for example, would be welcome if unspectacular changes To those recommendations we add a few of our own. One of the great ironies of intelligence is that those with the broadest and most relevant experience are the most likely to be denied clearance. Arabic speakers, for instance, usually have family and friends in the Arab world; this sets off alarm bells among counterintelligence officers. If the DNI is to implement the intelligence reform bills call for diversity, he must address this paradox. The current clearance process does not allow for much managerial input or appeal. If the counterintelligence staff denies clearance to a qualified applicant, managers have almost no recourse to appeal the decision. Due to privacy concerns, managers are often not even informed of the reason clearance was denied. Reforming the clearance process to allow applicants the opportunity to waive their right to privacy would allow managers greater ability to appeal if they believe the risk is acceptable.

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

13

Second, any increase in hiring should be accompanied by new professional training courses and field tours. Additional hiring would make it easier for analysts to develop professional expertise away from the office, because more full-time analysts can pick up the slack while they are away. For example, only one or two analysts currently cover many accounts at the CIA. The unrelenting demand for day-to-day reporting makes it difficult for them to find the time for area-specific and language training. Any additional slack in the system to alleviate this problem would be useful. But without establishing complementary training programs, the net result of expanded hiring will be to dilute the talent base. Coordination will also become more difficult as more people are brought on board. Third, the community must come to grips with the problem of retaining good analysts. Improving intelligence depends critically on the long process of cultivating professional experts. Unfortunately, it is no secret that many analysts can make more money in the private sector, both because of their specialized knowledge and because they hold security clearances. They may also leave government service to escape from policy and media scrutiny. Overcoming the retention problem will require solutions that insulate analysts from external pressure while demanding internal accountability. One possibility would be to expand the Senior Analyst Service and create more openings for dedicated analysts at higher pay grades. This would allow the community to isolate top analysts and provide personal and financial incentives for them to remain in government service. Absent such programs, the community is vulnerable to unstructured cycles of binge hiring and general purges.

Conclusion Although many of the 9/11 Commissions recommendations are now written into law, the story of intelligence reform is far from complete. The legislative language is vague, meaning that the process of implementation will be critically important. An informed debate on the theories of intelligence failure will be essential to ensuring that reform leads to improvement. The current high profile organizational changes offer a sense that the community is taking action. This is comforting, perhaps, but unlikely to do much good.

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

14

The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, The 9/11 Commission Report (New York: W.W. Norton, 2004), pp. 339-348. 2 9/11 Commission Report, p. 344. 3 9/11 Commission Report, p. 346. 4 9/11 Commission Report, p. 344. 5 Roger Z. George, Fixing the Problem of Analytical Mind-Sets: Alternative Analysis, International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Autumn 2004), pp. 385-404, at 391. 6 George, Fixing the Problem, and Stephen Marrin, CIAs Kent School: Improving Training for New Analysts, International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, Vo. 16, No. 4 (Winter 2003), pp. 609-637. 7 9/11 Commission Report, pp. 408-409. 8 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, S.2845, sec. 102A; http://thomas.loc.gov/cgibin/query/C?c108:./temp/~c108Lpf8R0. 9 Aaron Wildavsky, The Self-Evaluating Organization, Public Administration Review, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September/October 1972), pp. 509-520. 10 9/11 Commission Report, p. 411. 11 Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), pp. 117-202. 12 For an excellent history of intelligence-policy relations, see Christopher Andrew, For the Presidents Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush (New York: HarperCollins, 1995). For discussions of why policymakers ignore intelligence, see Richard Betts, Analysis, War, and Decision: Why Intelligence Failures are Inevitable, World Politics, Vol. 32, No. 1 (1978), pp. 61-89; Michael Handel, The Politics of Intelligence, Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 2, No. 4 (October 1987), pp. 5-46; Thomas L. Hughes, The Fate of Facts in a World of Men (New York: Foreign Policy Association, Headline Series No. 233, 1976); and Hans Heymann, Intelligence/Policy Relationships, in Alfred C. Maurer, Marion D. Tunstall, and James M. Keagle, eds., Intelligence: Policy and Process (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985), pp. 57-66. 13 The Commission actually called for a National Intelligence Director (NID), while the final legislation designated a Director of National Intelligence (DNI). For the sake of clarity we use only the latter title. 14 9/11 Commission Report, p. 415. 15 Diversity is a laudable goal because the intelligence community badly needs an injection of professional analysts with linguistic and area-specific expertise. Broader outreach efforts will also increase the available talent pool. But we must be very clear about the goals of diversity and the trade-offs involved. Past discussions have argued for diversity on legal and moral grounds, while remaining quite vague on the substantive impact of diversification. See, for example, Alton Dunham, Leading a Diverse Workforce into the 21st Century, Defense Intelligence Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1998), pp. 89-105. 16 The DNI shall establish a process and assign an individual or entity the responsibility for ensuring that, as appropriate, elements of the intelligence community conduct alternative analysisof the information and conclusions in intelligence products. Intelligence Reform Act, sec. 1017. 17 Intelligence Reform Act, secs. 1019-1020. 18 Intelligence Reform Act, sec. 1018. 19 9/11 Commission Report, p. 416. 20 Gregory F. Treverton, Reshaping National Intelligence for an Age of Information (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), pp. 167-176. 21 Intelligence Reform Act, sec. 2002. 22 9/11 Commission Report, pp. 427-428. 23 Intelligence Reform Act, secs. 7306-7307. 24 9/11 Commission Report, p. 353. 25 9/11 Commission Report, p. 353-354. The NSA had some information on the two terrorists in late 1999, but did little to follow up, as it was not asked to by any of its customers in the intelligence community. The CIA failed to appreciate the significance of the two names and did not launch a major effort to track

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

15

them prior to their entry into the U.S., though some efforts were made. This failure was compounded when the FBI was not informed that the two might attempt to enter the U.S. and therefore failed to place the names on a watchlist. 26 9/11 Commission Report, p. 357. 27 Tenet specifically designated Osama bin Laden a Tier 0 priority, the highest tier in the prioritization matrix then in use. See Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, From the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan to September 10, 2001 (New York: The Penguin Press, 2004), p. 435. 28 9/11 Commission Report, p. 357-358. 29 See Bill Owens with Ed Offley, Lifting the Fog of War (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2000). 30 See David Talbot, How Technology Failed in Iraq, MIT Technology Review, November 2004. 31 On the Myers-Briggs personality test administered by the CIA to new personnel, many analysts score as highly introverted, making the formation of these interagency relationships difficult apart from any bureaucratic restrictions. 32 The best example of the failure of centralization to solve infighting is provided by the history of the Secretary of Defense (SecDef). The SecDef was originally intended to coordinate the budget and actions of the Army, Air Force and Navy Departments. Yet after nearly four decades and several strong-willed SecDefs such as Robert McNamara, Congress concluded that the services were still just as fractious as ever. This led to the oft-heralded Goldwater-Nichols reform of 1986, promoting jointness between the services. Nearly twenty years after its passage, Goldwater-Nichols has not ended tension between services over priorities. At best it has mutated fierce competition between services into an exercise in log-rolling, so that each service gets its piece of the budgetary pie to spend as it wishes. The Air Force's continued pursuit of the expensive F/A-22 despite its unclear role in supporting near-term joint operations such as counterinsurgency is one example of this continuing problem. 33 I can look at a knot in a piece of wood, said poet William Blake, until it frightens me. 34 Winnefeld is quoted in Carl Connetta and Charles Knight, Dealing with Uncertainty: The New Logic of American Military Planning, Project on Defense Alternatives, February 1998; http://www.comw.org/pda/bullyweb.html. Futuristic weapons systems are also up against generous military pay and benefit policies. See James Flanigan, Troop Costs Take Bigger Bite out of DefenseContract Pie, Los Angeles Times, January 2, 2005, p. C1; and Cindy Williams, Making the Cuts, Keeping the Benefits, New York Times, January 11, 2005, p. 19. 35 Post-hoc reviews of Pearl Harbor, the Yom Kippur War, and the 1998 Indian nuclear test all emphasize this problem. On Congresss 1946 review of Pearl Harbor, see Roberta Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1962). On Israels post-mortem, see Ephraim Kahana, Early Warning Versus Concept: The Case of the Yom Kippur War, Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Summer 2002), pp. 81-104, and Eliot A. Cohen and John Gooch, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War (New York: Free Press, 1990), pp. 95-132. On the Jeremiah Commission report that examined the U.S. failure to anticipate Indias nuclear test, see Walter Pincus, Spy Agencies Faulted for Missing Indian Tests, Washington Post, June 3, 1998, p. A18. For a more general description of analytical tunnel vision, see Richard S. Heuer, Jr., Psychology of Intelligence Analysis (Washington, DC: CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence, 1999); ww.cia.gov/csi/books/19104/art3.html. 36 The basic response to 9/11 has been to increase the size and funding of the intelligence community. Its budget has risen by an estimated $10 billion since the attacks, and President Bush has called for a substantial increase in the number of analysts. Along with calls for more imagination, this heady expansion may undermine efforts to prioritize among threats. Stephen Daggett, The U.S. Intelligence Budget: A Basic Overview, Congressional Research Service, September 24, 2004; http://www.fas.org/irp/crs/RS21945.pdf. 37 Terms taken from conversations with intelligence community personnel. For additional examples of historic DIA-CIA tension, see Thomas Powers, The Man Who Kept the Secrets: Richard Helms and the CIA (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1979), p. 160-161, 173-176, and 212-213. 38 On the differences between the operational and analytic components of the CIA, see Powers, Man Who Kept the Secrets, p. 35-37. 39 9/11 Commission Report, p. 354. 40 9/11 Commission Report., pg. 353

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

16

Executive Order 12333, United States Intelligence Activities, December 4, 1981, section 1.12(b). Text available online at: http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/resource/speeches/1981/120481d.htm. 42 For more detailed discussion of Tenet's memo and the lack of response in the community, see Coll, Ghost Wars, p. 435-436. Coll argues that resource allocation could have been changed by the President and/or Congress and that Tenet's attempts to get more money for the war on terror were denied by both the White House and Congress. 43 This point is not a new one. The 1996 Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the U.S. Intelligence Community chaired by Harold Brown notes: Intelligence agencies cannot operate in a vacuum. Like any other service organization, intelligence agencies must have guidance from the people they serve. They exist as a tool of government to gather and assess information, and if they do not receive direction, chances are greater that resources will be misdirected and wasted. Intelligence agencies need to know what information to collect and when it is needed. They need to know if their products are useful and how they might be improved to better serve policymakers. Guidance must come from the top. Policymaker direction should be both the foundation and the catalyst for the work of the Intelligence Community. Preparing for the 21st Century: An Appraisal of U.S. Intelligence (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1996), p. 29. 44 Gregory F. Treverton and Peter A. Wilson, True Intelligence Reform is Cultural, Not Just Organizational Chart Shift, Christian Science Monitor, January 13, 2005; http://search.csmonitor.com/search_content/0113/p09s02-coop.html. 45 It has become almost axiomatic to call for greater coordination since September 11. But this is nothing new. Ray Cline, former Deputy Director of Central Intelligence and head of the State Departments Bureau of Intelligence and Research, best summed up the attitude of many to intelligence coordination: Being in favor of coordination in the US intelligence community has come to be like being against sin; everyone lines up on the right side of the question. In fact, coordination has become what Stephen Potter calls an "OK" word - one which defies precise definition but sounds good and brings prestige to the user. Yet Cline added, Now I do not want to deny that coordination is a good thing, but I would like to suggest that there can be too much of a good thing. I am afraid the intelligence community is suffering from overcoordination. Cline was writing in 1957, yet the same automatic belief in the absolute good of coordination is still held by many. Ray S. Cline, Is Intelligence Over-Coordinated? Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 1, No.4 (Fall 1957). 46 Jonathan Kirshner, Rationalist Explanations for War? Security Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Autumn 2000), pp. 143-150.

41

Breakthroughs, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 10-21.

17

You might also like

- Osint UsageDocument6 pagesOsint Usageabel_get2000100% (1)

- Mark Felt Deep Throat FBI Files PDFDocument243 pagesMark Felt Deep Throat FBI Files PDFJo Aqu ÍnNo ratings yet

- The Majestic 12 Documents and Excerpt of "The Occult Connection: UFO's, Secret Socieities, and Ancient Gods" by Ken HudnallDocument9 pagesThe Majestic 12 Documents and Excerpt of "The Occult Connection: UFO's, Secret Socieities, and Ancient Gods" by Ken HudnallGrave Distractions Publications50% (2)

- Senate Intelligence Committee Report Volume IVDocument158 pagesSenate Intelligence Committee Report Volume IVStefan Becket33% (3)

- Executive SummaryDocument13 pagesExecutive SummaryFox News100% (3)

- Historic FBI File: March On Washington Part 1 of 2Document324 pagesHistoric FBI File: March On Washington Part 1 of 2Smiley Hill0% (1)

- Senate Judiciary Committee - Kavanaugh ReportDocument414 pagesSenate Judiciary Committee - Kavanaugh ReportThe Conservative Treehouse100% (4)

- Cointelpro The Naked TruthDocument4 pagesCointelpro The Naked TruthDäv OhNo ratings yet

- Barbeito WarrantDocument19 pagesBarbeito WarrantcitypaperNo ratings yet

- The Intelligence Community Debate Over Intuition Versus Structured TechniqueDocument23 pagesThe Intelligence Community Debate Over Intuition Versus Structured TechniqueClaudia TeoodorescuNo ratings yet

- The State of Strategic IntelligenceDocument22 pagesThe State of Strategic IntelligenceJohn Adams100% (1)

- Mattis-Understanding Chinese IntelDocument11 pagesMattis-Understanding Chinese IntelyakmzzNo ratings yet

- U S D C: Nited Tates Istrict OurtDocument26 pagesU S D C: Nited Tates Istrict OurtJ RohrlichNo ratings yet

- Open Source Intelligence: Assessing the Open Source CenterDocument22 pagesOpen Source Intelligence: Assessing the Open Source CenterMyriam FeninaNo ratings yet

- Consolidating Intelligence Analysis Under The DNIDocument48 pagesConsolidating Intelligence Analysis Under The DNIJeremy LevinNo ratings yet

- Truman Loyalty Oath 1947Document4 pagesTruman Loyalty Oath 1947Anonymous nYwWYS3ntV100% (1)

- July 28 2023 Letter From Ranking Member Raskin To Chair ComerDocument11 pagesJuly 28 2023 Letter From Ranking Member Raskin To Chair ComerFile 411100% (1)

- The Role of Bias in Intelligence AnalysisDocument16 pagesThe Role of Bias in Intelligence AnalysisJeremy LevinNo ratings yet

- Intelligence As A Tool of StrategyDocument16 pagesIntelligence As A Tool of Strategyjoanirricardo100% (1)

- Charles E. Smith - Feasibility of Thermite Sparking With Impact of Rusted Steel Onto Aluminum Coated SteelDocument66 pagesCharles E. Smith - Feasibility of Thermite Sparking With Impact of Rusted Steel Onto Aluminum Coated SteelAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Applying The Intelligence Cycle Model To Counterterrorism Intelligence For Homeland SecurityDocument22 pagesApplying The Intelligence Cycle Model To Counterterrorism Intelligence For Homeland SecurityMatejic MilanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Intelligence A Concentrated and Diffused Intelligence ModelDocument17 pagesStrategic Intelligence A Concentrated and Diffused Intelligence ModelRisora BFNo ratings yet

- Strategic Intelligence for American National Security: Updated EditionFrom EverandStrategic Intelligence for American National Security: Updated EditionNo ratings yet

- Why Intelligence Fails: Lessons from the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq WarFrom EverandWhy Intelligence Fails: Lessons from the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Intelligence PaperDocument11 pagesIntelligence PaperDylan HenrichNo ratings yet

- Occasional Paper N O2 PDFDocument9 pagesOccasional Paper N O2 PDFAndrés Acosta HerreraNo ratings yet

- Arthur S. HulnickDocument23 pagesArthur S. HulnickJosé António RoseiroTeixeiraNo ratings yet

- 911 ShelbyDocument84 pages911 ShelbyGabi ZotaNo ratings yet

- T2 B15 1014 Hearing 2 of 2 John Deutch 739Document7 pagesT2 B15 1014 Hearing 2 of 2 John Deutch 739ucsd_researchNo ratings yet

- Chinese Cyber PowerDocument12 pagesChinese Cyber PowerAgung Guntomo RaharjoNo ratings yet

- Predictive, Net-Centric Intel, TimSmith, Galileo 2006Document16 pagesPredictive, Net-Centric Intel, TimSmith, Galileo 2006TimSmith56No ratings yet

- Better Ways To Fix US Intelligence - BerkowitzDocument11 pagesBetter Ways To Fix US Intelligence - BerkowitzFelipeMgrNo ratings yet

- CIA Research PaperDocument6 pagesCIA Research Paperyelbsyvkg100% (1)

- Truth To Power? Rethinking Intelligence Analysis: Gary J. SchmittDocument24 pagesTruth To Power? Rethinking Intelligence Analysis: Gary J. SchmittMoamen WahbaNo ratings yet

- Congressional Research ServiceDocument19 pagesCongressional Research ServiceDisclosure731No ratings yet

- Intelligence in 2021Document16 pagesIntelligence in 2021J. K.No ratings yet

- FO B2 Public Hearing 10-14-03 FDR - Tab 2 - Suggested Questions On Leadership of US Intelligence 647Document2 pagesFO B2 Public Hearing 10-14-03 FDR - Tab 2 - Suggested Questions On Leadership of US Intelligence 6479/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- WMD Commission Report, 2005Document618 pagesWMD Commission Report, 2005shmouseNo ratings yet

- CIA and Executive Failures Prevented 9/11 AttacksDocument6 pagesCIA and Executive Failures Prevented 9/11 AttacksBailey DaltonNo ratings yet

- ©fftce of Tye Jjepttu Ttnrneu: TefafsssslfDocument13 pages©fftce of Tye Jjepttu Ttnrneu: Tefafsssslf9/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- Home Missing IntelligenceDocument2 pagesHome Missing IntelligenceGeovani Hernandez MartinezNo ratings yet

- Marrin EvaluatingtheQualityofIntelligenceAnalysisDocument14 pagesMarrin EvaluatingtheQualityofIntelligenceAnalysisStephen MarrinNo ratings yet

- BattlespaceAwareness PDFDocument17 pagesBattlespaceAwareness PDFYesika RamirezNo ratings yet

- Marrin - Homeland Security and The Analysis of Foreign Intelligence - Markle 2002Document17 pagesMarrin - Homeland Security and The Analysis of Foreign Intelligence - Markle 2002Stephen MarrinNo ratings yet

- The U.S. Intelligence Community: History, Role, and OrganizationDocument7 pagesThe U.S. Intelligence Community: History, Role, and OrganizationPatriciaSugpatanNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Crime RatesDocument11 pagesResearch Paper On Crime Ratesepfdnzznd100% (1)

- Occasional Paper - Strategic Considerations For Philippine Cyber SecurityDocument15 pagesOccasional Paper - Strategic Considerations For Philippine Cyber SecurityStratbase ADR InstituteNo ratings yet

- 13dec Swedlow AndrewDocument73 pages13dec Swedlow AndrewMark StanhopeNo ratings yet

- National Intelligence Reforms: Background: The Attacks On The United States On September 11,2001 Exposed SevereDocument6 pagesNational Intelligence Reforms: Background: The Attacks On The United States On September 11,2001 Exposed Severe9/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- Developing Tomorrow's Intelligence AnalystDocument4 pagesDeveloping Tomorrow's Intelligence Analystshakes21778No ratings yet

- T2 B2 10-14-03 Hearing - Intelligence Background 2 of 3 FDR - Tab 15 - Undated Briefing Paper - National Intelligence Reforms - 2 Pgs 912Document2 pagesT2 B2 10-14-03 Hearing - Intelligence Background 2 of 3 FDR - Tab 15 - Undated Briefing Paper - National Intelligence Reforms - 2 Pgs 9129/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- RL32597 - Info Sharing For HLSDocument38 pagesRL32597 - Info Sharing For HLSChrisBecknerNo ratings yet

- Border Drones Affirmative - Northwestern 2015 6WSDocument79 pagesBorder Drones Affirmative - Northwestern 2015 6WSMichael TangNo ratings yet

- Marrin - CIA Kent School and University-2000Document3 pagesMarrin - CIA Kent School and University-2000Stephen MarrinNo ratings yet

- Competencies Needed for Different Types of Intelligence AnalysisDocument35 pagesCompetencies Needed for Different Types of Intelligence AnalysisPapa Yp IusNo ratings yet

- Sample Policy MemoDocument2 pagesSample Policy MemoTong LinNo ratings yet

- SSH Assignment Tayyab (22-ARID-1189)Document4 pagesSSH Assignment Tayyab (22-ARID-1189)TerimaakichutNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT (Centring On Int-Policy Relations)Document1 pageABSTRACT (Centring On Int-Policy Relations)Gcwelumusa Chrysostomus KhwelaNo ratings yet

- Question and Answer Ic Post 911Document5 pagesQuestion and Answer Ic Post 911Anonymous QvdxO5XTRNo ratings yet

- Iac Foreign Intelligence Program 15 Aug 1952Document13 pagesIac Foreign Intelligence Program 15 Aug 1952api-52146767No ratings yet

- Radical Technological Innovation in Satellite Reconnaissance: From CORONA To CLASSIC WizardDocument28 pagesRadical Technological Innovation in Satellite Reconnaissance: From CORONA To CLASSIC WizardVisal SasidharanNo ratings yet

- Joy Rafael PrivadoDocument7 pagesJoy Rafael PrivadoKimuel Robles ArdienteNo ratings yet

- T2 B4 Mellon Letter FDR - Entire Contents - Letter From Christopher Mellon Re Intelligence Community Structure 596Document4 pagesT2 B4 Mellon Letter FDR - Entire Contents - Letter From Christopher Mellon Re Intelligence Community Structure 5969/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- CCTV Cctv-Cover CDRDocument39 pagesCCTV Cctv-Cover CDRRendy Adam FarhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2, Section 3 - China's Intelligence Services and Espionage Threats To The United StatesDocument24 pagesChapter 2, Section 3 - China's Intelligence Services and Espionage Threats To The United StatesRamadani pasaribuNo ratings yet

- The U.S. Intelligence Community Is Not Prepared For The China Threat - Foreign AffairsDocument8 pagesThe U.S. Intelligence Community Is Not Prepared For The China Threat - Foreign AffairsSyed Ali WajahatNo ratings yet

- Covert Action and Clandestine Activities of The Intelligence Community: Selected Definitions in BriefDocument13 pagesCovert Action and Clandestine Activities of The Intelligence Community: Selected Definitions in BriefGlen YNo ratings yet

- 1971-07-30 Smith and Marshall To Kissinger PDFDocument2 pages1971-07-30 Smith and Marshall To Kissinger PDFJamesWilsonNo ratings yet

- CIA Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesCIA Research Paper Topicsuylijwznd100% (1)

- T2 B5 Teams Major Policy Issues FDR - Entire Contents - Memo Re Major Policy Issues Under Consideration - by Team 609Document6 pagesT2 B5 Teams Major Policy Issues FDR - Entire Contents - Memo Re Major Policy Issues Under Consideration - by Team 6099/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Framework for Adapting National Intelligence for Domestic Law EnforcementFrom EverandA Comprehensive Framework for Adapting National Intelligence for Domestic Law EnforcementNo ratings yet

- Boris Khasainov, Allen Kuhl and Sergey Victorov - Equilibrium-Chemistry Model For Multiphase Reactive Premixed and Nonpremixed FlowsDocument4 pagesBoris Khasainov, Allen Kuhl and Sergey Victorov - Equilibrium-Chemistry Model For Multiphase Reactive Premixed and Nonpremixed FlowsAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Timothy J. Campbell Et Al - Oxidation of Aluminum NanoclustersDocument14 pagesTimothy J. Campbell Et Al - Oxidation of Aluminum NanoclustersAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Allen L. Kuhl - Thermodynamics of Combustion of TNT Products in A ChamberDocument7 pagesAllen L. Kuhl - Thermodynamics of Combustion of TNT Products in A ChamberAlarmakNo ratings yet

- T.M. Tillotson Et Al - Sol-Gel Processing of Energetic MaterialsDocument13 pagesT.M. Tillotson Et Al - Sol-Gel Processing of Energetic MaterialsAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Steven W. Dean - The Influence of Gas Generation On Flame Propagation For Nano-Al Based Energetic MaterialsDocument51 pagesSteven W. Dean - The Influence of Gas Generation On Flame Propagation For Nano-Al Based Energetic MaterialsAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Michael E. Brown, Steven J. Taylor and Michael J. Tribelhorn - Fuel-Oxidant Particle Contact in Binary Pyrotechnic ReactionsDocument8 pagesMichael E. Brown, Steven J. Taylor and Michael J. Tribelhorn - Fuel-Oxidant Particle Contact in Binary Pyrotechnic ReactionsPomaxxNo ratings yet

- Bryan S. Bockmon - Burn Rates in Nano-Composite Energetic MaterialsDocument39 pagesBryan S. Bockmon - Burn Rates in Nano-Composite Energetic MaterialsAlarmakNo ratings yet

- C. Rossi and D. Esteve - Micropyrotechnics, A New Technology For Making Energetic Microsystems: Review and ProspectiveDocument32 pagesC. Rossi and D. Esteve - Micropyrotechnics, A New Technology For Making Energetic Microsystems: Review and ProspectiveAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Ashish Rai Et Al - Importance of Phase Change of Aluminum in Oxidation of Aluminum NanoparticlesDocument3 pagesAshish Rai Et Al - Importance of Phase Change of Aluminum in Oxidation of Aluminum NanoparticlesAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Allen L. Kuhl and John B. Bell - Thermodynamic Solution For Combustion of PETN/TNT Products With AirDocument11 pagesAllen L. Kuhl and John B. Bell - Thermodynamic Solution For Combustion of PETN/TNT Products With AirAlarmakNo ratings yet

- T.M. Tillotson Et Al - Nanostructured Energetic Materials Using Sol-Gel MethodologiesDocument8 pagesT.M. Tillotson Et Al - Nanostructured Energetic Materials Using Sol-Gel MethodologiesPomaxxNo ratings yet

- Kaili Zhang Et Al - A Nano Initiator Realized by Integrating Al/CuO-Based Nanoenergetic Materials With A Au/Pt/Cr MicroheaterDocument5 pagesKaili Zhang Et Al - A Nano Initiator Realized by Integrating Al/CuO-Based Nanoenergetic Materials With A Au/Pt/Cr MicroheaterAlarmakNo ratings yet

- K. Park Et Al - Size-Resolved Kinetic Measurements of Aluminum Nanoparticle Oxidation With Single Particle Mass SpectrometryDocument10 pagesK. Park Et Al - Size-Resolved Kinetic Measurements of Aluminum Nanoparticle Oxidation With Single Particle Mass SpectrometryAlarmakNo ratings yet

- A. Prakash, A. V. McCormick and M. R. Zachariah - Tuning The Reactivity of Energetic Nanoparticles by Creation of A Core-Shell NanostructureDocument4 pagesA. Prakash, A. V. McCormick and M. R. Zachariah - Tuning The Reactivity of Energetic Nanoparticles by Creation of A Core-Shell NanostructureAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Kaili Zhang, Carole Rossi and G. A. Ardila Rodriguez - Development of A nano-Al/CuO Based Energetic Material On Silicon SubstrateDocument4 pagesKaili Zhang, Carole Rossi and G. A. Ardila Rodriguez - Development of A nano-Al/CuO Based Energetic Material On Silicon SubstrateAlarmakNo ratings yet

- L. Menon Et Al - Ignition Studies of Al/Fe2O3 Energetic NanocompositesDocument3 pagesL. Menon Et Al - Ignition Studies of Al/Fe2O3 Energetic NanocompositesAlarmakNo ratings yet

- WTC ThermitaDocument13 pagesWTC ThermitarobertorojasfeijoNo ratings yet

- S. F. Son Et Al - Combustion of Nanoscale Al/MoO3 Thermite in MicrochannelsDocument1 pageS. F. Son Et Al - Combustion of Nanoscale Al/MoO3 Thermite in MicrochannelsAlarmakNo ratings yet

- A. Rai Et Al - Understanding The Mechanism of Aluminium Nanoparticle OxidationDocument17 pagesA. Rai Et Al - Understanding The Mechanism of Aluminium Nanoparticle OxidationPomaxxNo ratings yet

- S. Apperson Et Al - Generation of Fast Propagating Combustion and Shock Waves With Copper Oxide/aluminum Nanothermite CompositesDocument3 pagesS. Apperson Et Al - Generation of Fast Propagating Combustion and Shock Waves With Copper Oxide/aluminum Nanothermite CompositesPomaxxNo ratings yet

- M. Comet and D. Spitzer - Elaboration and Characterization of Nano-Sized AlxMoyOz/AI ThermitesDocument13 pagesM. Comet and D. Spitzer - Elaboration and Characterization of Nano-Sized AlxMoyOz/AI ThermitesAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Valery I. Levitas Et Al - Mechanochemical Mechanism For Fast Reaction of Metastable Intermolecular Composites Based On Dispersion of Liquid MetalDocument20 pagesValery I. Levitas Et Al - Mechanochemical Mechanism For Fast Reaction of Metastable Intermolecular Composites Based On Dispersion of Liquid MetalAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Valery I. Levitas Et Al - Melt Dispersion Versus Diffusive Oxidation Mechanism For Aluminum Nanoparticles: Critical Experiments and Controlling ParametersDocument3 pagesValery I. Levitas Et Al - Melt Dispersion Versus Diffusive Oxidation Mechanism For Aluminum Nanoparticles: Critical Experiments and Controlling ParametersAlarmakNo ratings yet

- S. F. Son - Energetic Materials Combustion Laboratory (EMCL)Document8 pagesS. F. Son - Energetic Materials Combustion Laboratory (EMCL)AlarmakNo ratings yet

- Valery I. Levitas Et Al - Melt Dispersion Mechanism For Fast Reaction of NanothermitesDocument6 pagesValery I. Levitas Et Al - Melt Dispersion Mechanism For Fast Reaction of NanothermitesAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Modern History of Al-Qaeda and Terrorism Against The USA: 1979-2008Document91 pagesModern History of Al-Qaeda and Terrorism Against The USA: 1979-2008AlarmakNo ratings yet

- LNG Storage & TransportDocument5 pagesLNG Storage & TransportAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Tom Bender - LNG Imports: Neither Safe Nor WiseDocument11 pagesTom Bender - LNG Imports: Neither Safe Nor WiseAlarmakNo ratings yet

- Pcast: President's Council of Advisors On Science and TechnologyDocument26 pagesPcast: President's Council of Advisors On Science and TechnologyGouri UplenchwarNo ratings yet

- Statement of Qualifications: ASCLD/LAB-InternationalDocument6 pagesStatement of Qualifications: ASCLD/LAB-InternationalAkindele O AdigunNo ratings yet

- Document 157Document3 pagesDocument 157shazmin escalanteNo ratings yet

- Testimony of Special Agent Robert Schaefer After Being Accused of Doing A Fake Investigation Into The Police Impersonating FBI AgentsDocument10 pagesTestimony of Special Agent Robert Schaefer After Being Accused of Doing A Fake Investigation Into The Police Impersonating FBI AgentsGuy Madison NeighborsNo ratings yet

- Empagawards 04Document21 pagesEmpagawards 04politixNo ratings yet

- Robin Ducore AffidavitDocument8 pagesRobin Ducore Affidavittom clearyNo ratings yet

- Manager or Corporate SecurityDocument2 pagesManager or Corporate Securityapi-121417524No ratings yet

- Iseetrust Delitos InternacionalesDocument1 pageIseetrust Delitos InternacionalesGonzalo Tarifa IllanesNo ratings yet

- Fluid Terror Threat: A Genealogy of The Racialization of Arab, Muslim, and South Asian AmericansDocument34 pagesFluid Terror Threat: A Genealogy of The Racialization of Arab, Muslim, and South Asian AmericansjunaidkabirNo ratings yet

- I786 Credit Card Payment Form 06012020Document1 pageI786 Credit Card Payment Form 06012020Dayana HernandezNo ratings yet

- American Dissident Prince Judge MatthewDocument25 pagesAmerican Dissident Prince Judge MatthewIgnita Veritas University Law CentreNo ratings yet

- Criminal Investigation 3rd Edition Brandl Test BankDocument25 pagesCriminal Investigation 3rd Edition Brandl Test BankMelissaBakerijgd100% (66)

- Trump Presidency 33 - May 5th, 2018 To May 14th, 2018Document513 pagesTrump Presidency 33 - May 5th, 2018 To May 14th, 2018FW040100% (1)

- Affidavit in Support of A Criminal ComplaintDocument10 pagesAffidavit in Support of A Criminal ComplaintDaily KosNo ratings yet

- Covenant The Sword The Arm of The Lord Part01Document70 pagesCovenant The Sword The Arm of The Lord Part01api-278549254No ratings yet

- CIA ResumeDocument7 pagesCIA Resumec2r7z0x9100% (1)

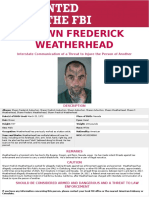

- Shawn Frederick WeatherheadDocument2 pagesShawn Frederick WeatherheadSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNo ratings yet

- Michael Seelman Leadership Coach ProfileDocument9 pagesMichael Seelman Leadership Coach ProfileALI HUSSAINNo ratings yet

- 2021-09-09 Calvert County TimesDocument32 pages2021-09-09 Calvert County TimesSouthern Maryland OnlineNo ratings yet

- Elias Diggins Arrest ReportDocument3 pagesElias Diggins Arrest ReportMichael_Lee_RobertsNo ratings yet