Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CHP Obesity 2005

Uploaded by

angus83Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CHP Obesity 2005

Uploaded by

angus83Copyright:

Available Formats

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Central Health Education Unit Centre for Health Protection Department of Health 2005

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Department of Health Copyright 2005

Produced and published by Central Health Education Unit, Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 7/F, Southorn Centre, 130 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong. Copies of this publication are available from the Central Health Education Unit and from the website http://www.cheu.gov.hk.

Printed by the Government Logistics Department (Printed with environmentally friendly ink on paper made from woodpulp derived from sustainable forests) Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Foreword

Obesity is a major public health problem worldwide. Its rising trend is evident in both developed and developing countries. There is also a significant increasing trend among the younger age groups to become obese. Hong Kong is also affected by the global epidemic of obesity. Local data suggest that 20.1% of men and 15.9% of women are overweight, and 22.3% of men and 20.0% of women are obese.i Obesity threatens our health and creates an enormous burden to our society. It results in ill health, reduced quality of life, premature deaths, increased health care costs and reduced productivity. Urgent actions are required to address the obesity epidemic. The Department of Health of the HKSAR Gover nment is committed to reducing the prevalence of obesity in Hong Kong. However, to effectively manage the obesity epidemic, everyone in the community must take responsibility and action. The synergy generated from our collaborative efforts will enable us to tackle the whole range of factors that contribute to the obesity epidemic. This document serves as the first step in our campaign against obesity. It aims to: 1. increase awareness of the problem of obesity/ overweight among health promoters and relevant stakeholders;

2.

encourage health promoters to adopt evidencebased initiatives in the management of obesity/ overweight in the population; and

3.

facilitate planning and development of strategies for managing obesity/overweight in the population.

The contents of this document include: 1. an overview of the problem of obesity and overweight, and their consequences both locally and globally; 2. 3. a brief introduction of the different initiatives conducted locally and overseas; and a summary of the effectiveness of various antiobesity initiatives. There are a number of ways to manage obesity. They range from preventive measures that maintain healthy weight and prevent weight gain to treatment options such as dietary modification, physical activity, behavioural therapy, drug therapy, combined therapy and surgery. The discussion in this document, however, is confined to initiatives that prevent obesity/overweight. Treatment of obesity/ overweight using medications and different therapies is beyond the scope of this document. Furthermore, this document mainly makes reference to initiatives known to the Department of Health.

Dr Ray Y L CHOY

Head, Central Health Education Unit, Department of Health

Department of Health. Population Health Survey 2003/2004 (provisional data). Hong Kong: Department of Health.

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions i

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

vi

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Contents

Foreword List of Tables List of Charts List of Diagrams Abbreviations CHAPTER 1 HOW DO WE MEASURE OBESITY? Adulthood Obesity Childhood Obesity WHY SHOULD WE BE CONCERNED ABOUT OBESITY? Physical Problems Psychosocial Problems Deaths Childhood and Adolescence Obesity Economic Costs HOW COMMON IS OBESITY? Global Situation Obesity in Hong Kong Obesity Related Diseases in Hong Kong Dietary Habits and Physical Activity of Hong Kong People WHO ARE AT RISK? Biological Factors Nutrition Physical Activity Environmental Factors Micro-environments Macro-environments INITIATIVES TO PREVENT OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY Infancy Childhood and Adolescence Adulthood Old Age General (all age) Environment and Policy RECOMMENDATIONS

i iv iv v v 1 2 5 7 8 9 9 9 10 11 12 12 15 15 17 18 18 19 20 20 21 23 24 27 31 33 35 36 41 46 60 65 66

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6 References Appendices Resources Link Glossary

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

iii

List of Tables List of Charts

List of Tables

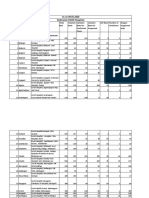

1.1 Classification of BMI and risk of co-morbidities 1.2 Co-morbidities risk associated with different levels of BMI and ranges of waist circumference in adult Asians in 2000 1.3 Recommended sex-specific cut-off points of waist circumference by WHO and WHO WPRO 2.1 Relative risk of health problems associated with obesity 3.1 Prevalence of obesity by gender in Hong Kong, 1995-1996 3.2 Prevalence of obesity by gender in Hong Kong, 2003 (self-reported data) 3.3 Prevalence of obesity by gender in Hong Kong, 2003/2004 (provisional data) 5.1 Ten steps to successful breastfeeding 5.2 Summary of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes 5.3 Definition of one serving size of fruit and vegetable 5.4 Items for sale at tuckshops (extract of guidelines on meal arrangements in schools) 5.5 Lunch box ingredients (extract of guidelines on meal arrangements in schools) 3 3 5 9 12 13 13 25 26 29 38 40

List of Charts

1.1 Median BMI by age and gender in six nationally representative datasets 2.1 Relationship between BMI and relative risk of mortality 6 10

3.1 Prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI 23) by age group and sex in Hong Kong, 2003/2004 14 3.2 Prevalence of childhood obesity in primary schools by gender and school year in Hong Kong, 1997-2002 3.3 Prevalence of childhood obesity in secondary schools by gender and school year in Hong Kong, 1997-2002 14 14

iv

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

List of Diagrams Abbreviations

List of Diagrams

1.1 Measuring tape position for waist circumference in adults 5.1 An advertisement of promoting breastfeeding in MTR station in 2003 5.2 Promoting breastfeeding - Baby Expo 2003 5.3 Healthy Eating Movement for kindergartens and nurseries in 1999 5.4 An example of exercise prescription prescribed by doctors 5.5 Posters and stickers of point-of-decision prompts in public housing estates 5.6 Consultation paper on labelling scheme on nutrition information, issued by Health, Welfare and Food Bureau in November 2003 4 26 27 30 31 35 39

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this report: AIDS BFHI BMI DH EMB IASO IOTF NCD NGO PE SES UNICEF WHO WPRO Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative Body Mass Index Department of Health Education and Manpower Bureau International Association for the Study of Obesity International Obesity Task Force Non-Communicable Disease Non-Governmental Organisation Physical Education Socio Economic Status United Nations Childrens Fund World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Chapter 1 How do we measure obesity?

1.1 Overweight refers to an abnormally high body

weight which may come from bone, lean muscle, fat tissue and water. Obesity is a condition in which the body stores an excessive amount of fat to such an extent that health may be adversely affected.1-3

simple and inexpensive tools for obesity assessment. Reference criteria have been set up for the purposes of defining obesity and identifying associated health risks. It should, however, be noted that they are only guidelines and should not be the sole cr iter ion to determine whether an individual is overweight or obese.

1.2 A certain amount of fat is necessary for normal

body functions such as energy storage, heat insulation, protection of vital organs and carrier for fat-soluble vitamins, etc.

Adulthood Obesity

Body mass index

1.6 Body mass index (BMI) is an internationally 1.3 Our body can normally regulate overall energy

intake with overall energy expenditure without a persistent change in body weight. It is only when energy intake exceeds energy used for a considerable period of time that obesity is likely to develop. recognised measurement of obesity for adults based on weight and height. It is calculated by dividing a persons weight in kilograms by the square of his/her height in metres (BMI= weight in kg/ (height in m)2).

1.7 BMI is the most commonly used method of 1.4 Overweight and obesity can be measured by

assessing weight and height as well as the amount and distr ibution of body f at. Computerised tomography (CT), dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are examples of body fat measurement but they are usually not the preferred methods by health professionals because of high cost and sophisticated equipment required. obesity classification among scientific researchers and health institutes of different countries. It is economical and highly practical because height and weight can be easily obtained without demanding sophisticated skills and equipment. Moreover, BMI is strongly correlated with the degree of fatness and obesity-related health risks (co-morbidities). Therefore, it is used by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the international s t a n d a rd o f o b e s i t y d e f i n i t i o n . T h e recommended BMI classifications and associated risk of co-morbidities are shown in table 1.1.

1.5 Instead of direct measurement of body fat,

body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and growth charts serve as

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

How do we measure obesity?

Table 1.1

Classification of BMI and risk of co-morbidities2 BMI (kg/m2) < 18.50 18.50-24.99 25.00 25.00-29.99 30.00-34.99 35.00-39.99 40.00 Risk of co-morbidities Low (with increased risk of clinical problems related to underweight) Average Increased Moderate Severe Very severe cut-off point for the Asian populations. These recommendations were based on studies suggesting that obesity-related health risks occur red at lower BMI in certain Asian populations (including Hong Kong Chinese) which were prone to general and central obesity. 4 Table 1.2 shows the proposed re f e re n c e r a n g e s f o r B M I a n d wa i s t circumferences and their related comorbidities risk in adult Asians.

Classification Underweight Normal range Overweight Pre-obese Obese class I Obese class II Obese class III

1.8 As the risk of co-morbidities in relation to

BMI differs among different ethnic groups, different cut-off values have been proposed to classify overweight and obesity for different populations. In 2000, a joint expert panel of the Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO) of the WHO, the International O b e s i t y Ta s k Fo rc e ( I OT F ) a n d t h e International Association for the Study of Obesity (IASO) recommended a lower BMI Table 1.2

Co-morbidities risk associated with different levels of BMI and ranges of waist circumference in adult Asians in 2000 4 BMI (kg/m )

2

Classification

Risk of co-morbidities Waist circumference < 90 cm (men) < 80 cm (women) 90 cm (men) 80 cm (women) Average

Underweight

< 18.5

Low (with increased risk of clinical problems related to underweight) Average Increased Moderate Severe

Normal range Overweight At risk Obese I Obese II

18.5 - 22.9 23 23 - 24.9 25 - 29.9 30

Increased Moderate Severe Very severe

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

How do we measure obesity?

1.9

Although the WHO experts did not recommend re-defining BMI cut-off points for different populations after reviewing the proposal, they suggested Asian countries define obesity-related health risks for their populations based on national data and considerations. A few Asian countries such as mainland China and Japan have developed their own BMI cutoff points for obesity classifications.

the elderly) may be classified as normal even when they are overweight. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio

1.11 The health risk associated with obesity is

determined not only by the amount of excessive fat being stored in the body but also where it is stored.2;5 Excess abdominal fat (central obesity) is as great a risk factor for developing diseases as excess body fat itself. It can be identified by measur ing waist circumference or calculating waist-to-hip ratio.

1.10 Despite its wide acceptance, BMI has its

limitations. BMI is neither age-nor sexspecific. It does not provide a direct estimation of body fat accumulation. Thus it may not be suitable for certain population groups. For example, athletes and individuals with large body frame and muscle bulk may wrongly fall into the obese group, while those who have reduced lean muscle mass (such as

1.12 Waist circumference correlates closely with

BMI6 and is a rough estimation of the amount of abdominal fat7-8 and total body fat9 that a body holds. It is measured at the midpoint between the lower border of the rib cage and the iliac crest (Diagram 1.1).

Diagram 1.1 Measuring tape position for waist circumference in adults

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

How do we measure obesity?

1.13 People of different sexes and ethnic origins

differ in the level of risk associated with a particular waist circumference. Table 1.3 shows the international recommendations made by WHO and the recommendations for adult Asians by WHO WPRO. Table 1.3 Gender Recommended sex-specific cut-off points of waist circumference by WHO and WHO WPRO 2;4 WHO recommendations (1998) Men Women < 94 cm < 80 cm WHO Western Pacific Region Office recommendations for adult Asians (2000) < 90 cm < 80 cm

1.14 The waist-hip ratio (WHR) is another

measure of abdominal obesity. It correlates closely with waist circumference. WHR is calculated by dividing the waist measurement (taken at its narrowest point) by the hip measurement (taken at its widest point). For example, a woman with a 76 cm waist and 94 cm hip would have a WHR of 0.81 (76 divided by 94 = 0.81). A WHR value greater than 1.0 in men or 0.85 in women indicates an excess in abdominal fat accumulation and an increased health risk.10

9

Growth charts

1.16 Reference charts for growth based on weightfor-age and height-for-age have been produced in different countries. However, the charts only compare the size of a child with that of other children of the same age. They do not take into account the variation in growth among these children. Therefore, an index of weight adjusted for height can provide a better measure of fatness.

1.17 In the Hong Kong Growth Survey 1993, sexspecific reference charts of weight-for-height (Appendix 1) along with a series of growth charts were developed for local references. 1112

Childhood Obesity 1.15 Measuring overweight and obesity in children

and adolescents is difficult because their rates in gaining weight and height vary during developmental stages. At present, there is no universally accepted method to measure childhood obesity.

The survey was a territory-wide cross-

sectional growth survey which covered around 25,000 Hong Kong Chinese children from birth to 18 years of age. Childhood obesity in this survey was defined as weight

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

How do we measure obesity?

> median weight for height x 120%. For example, if the height of a child is 140 cm, the corresponding median weight-for-height is 35kg. If his/her weight is greater than 42kg (35kg x 120%), then he/she is defined as obese. BMI-for-age reference curves

1.19 An international BMI-for-age reference curve

for defining overweight and obesity in children 2 to 18 years of age has been developed jointly by the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the IOTF in 2000 (see Appendix 2). The reference population was obtained from six large nationally representative cross-sectional growth surveys in the US, the UK, the Netherlands, Brazil, Hong Kong and Singapore. These surveys had over 10,000 subjects each and together covered 97,876 males and 94,851 females from birth to 25 years of age (Chart 1.1).13 This may help provide internationally comparable prevalence rates of overweight and obesity in children.

1.18 As for adults, BMI provides a useful measure

of fatness in children. However, BMI in children varies substantially with age. It rises steeply in infancy, falls during the preschool year s and r ises again dur ing adolescence. Therefore, BMI in children needs to be assessed using age-related reference curves.2

Chart 1.1

Median BMI by age and gender in six nationally representative datasets (from Brazil, Hong Kong, Netherlands, Singapore, the UK and the US) from an international growth survey in 200013

Brazil Great Britain Hong Kong Netherlands 23 Singpore United States

Body mass index (kg/m2)

23

Males

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Age (years) 14 16 18 20 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 0

Females

10 12 Age (years)

14

16

18

20

For adults, the most widely accepted criteria for obesity are based on BMI. For children, there is no universally agreed method to measure obesity.

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 6

Chapter 2 Why should we be concerned about obesity?

2.1 Obesity poses a growing threat to public health

all over the world. It is prevalent in both developed and developing countries, and affects men as well as women, children as well as adults. Gradually replacing the more traditional public health concerns such as under-nutrition and infectious diseases, obesity has become one of the most significant contributors to ill health. Obesity brings about health consequences that range from physical to psychosocial problems and results in conditions that vary from nonfatal conditions affecting the quality of life to premature death.

2.5 Obesity is associated with the development of

musculoskeletal problems, e.g. osteoarthritis at major weight-bearing joints in the knees, hips and lower back may be caused by extra weight. Gout is also more common among overweight people.

2.6 In women, obesity is related to several

reproductive disorders including infertility, general menstrual disorders and poor pregnancy outcome.

2.7 Sleep apnoea is a sleeping disorder suffered by

many obese people. The airway at the back of the throat collapses as an individual breathes in during his/her sleep. It can cause daytime sleepiness, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure and even sudden death.

Physical Problems 2.2 Health problems associated with obesity have

been studied in various industrialised countries. There is strong and consistent evidence on the relationship between obesity and risk of ill health. Alarmingly, the association begins at a not very high level of BMI.2

2.3 Obesity is associated with lipid disorders termed

dyslipidaemia and through which, it makes an individual more vulnerable to a number of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases including coronary heart disease, hypertension and stroke.

2.4 Overweight and obese people are more likely

to develop type II diabetes mellitus which is a major cause of early death, heart diseases, kidney diseases, stroke and blindness.

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 8

Why should we be concerned about obesity?

Table 2.1

Relative risk of health problems associated with obesity2 Moderately increased by two- to three-fold Coronary heart diseases Hypertension Osteoarthritis Gout Slightly increased by one- to two-fold Certain forms of cancers (breast cancer in postmenopausal women and colon cancer) Reproductive hormonal abnormalities Low back pain Impaired fertility psychosocial functioning. Studies

Greatly increased by more than three-fold Diabetes mellitus Gall bladder diseases Abnormal lipid or cholesterol levels Sleep apnoea

2.8 Table 2.1 summarises the increase in risk of

health problems associated with obesity.

consistently showed an inverse relationship between body weight and both overall selfesteem and body image among adolescents.15 Overweight in adolescence may also be associated with social and economic problems in adulthood.14

2.9 The WHO estimates that globally approximately

58% of diabetes mellitus, 21% of ischaemic heart disease and 8 to 42% of certain cancers are attributable to BMI greater than 21 kg/m .

2 1

Psychosocial Problems 2.10 Obesity is associated with a number of

psychosocial problems including body shape dissatisfaction and eating disorders. People with obesity are often confronted with social bias, prejudice and discrimination.14

Deaths 2.13 The death rate increases with rising degree

of overweight, as measured by BMI. The increase in death rate with rising BMI is steeper for both men and women under the age of 50. Moreover, the overweight effect persists well into the ninth decade of life.16-18 The death rate increases greatly at a BMI above 30kg/m2 (Chart 2.1).19 Studies for all adults implied a similar relationship between BMI and risk of mortality.2

2.11 The mechanisms leading to impaired

psychological well-being are different from those leading to physical illness. It is important to acknowledge that undesirable psychosocial consequences of obesity are derived from labelling effect that regards fatness as unhealthy and ugly.

Childhood and Adolescence Obesity 2.14 Studies have shown a tendency for obese

children to remain obese in adulthood. 21 Childhood obesity is also associated with elevated r isk factors for cardiovascular

2.12 A common consequence of obesity in

childhood and adolescence relates to

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Why should we be concerned about obesity?

Chart 2.1

Relationship between BMI and relative risk of mortality 20

Average risk

2.5

Moderate risk

High risk

2.0

Relative risk

1.5

1.0

0.5

20

25

30

35

BMI

diseases such as raised blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance and elevated fasting glucose; all these factors can continue into adulthood.

21-22

Economic Costs 2.17 Overweight and obesity, together with their

associated health problems, have substantial economic impact on the health care system by bringing about both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs refer to those incurred by the preventive, diagnostic and treatment services related to overweight and obesity (for example, doctor consultations, hospitalisation and nursing home care). Indirect costs refer to the loss in wages for people unable to work because of illness or disabilities as well as the loss in future earnings caused by premature death. Little data are available for quantifying the economic consequences of obesity in Asian countries.

In particular, childhood

obesity is associated with early development of type II diabetes mellitus.

2.15 Childhood obesity can lead to orthopaedic

complications due to excessive weight bearing upon joints.2 The most serious conditions include slipped capital femoral epiphyses in which the hip joint is forced out of the alignment, and bone growth deformities such as Blounts disease.

2.16 Obstructive sleep apnoea is another important

complication of childhood obesity and can lead to hypoventilation, daytime sleepiness and in rare cases, sudden death.

2

Obesity not only causes human sufferings from ill health, but also creates significant economic burden to the society. Direct economic costs of obesity assessed in several developed countries are in the range of 2 to 7% of total health care costs.2

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

10

Chapter 3 How common is obesity?

Global Situation 3.1 The WHO estimated that more than one billion

adults are overweight and at least 300 million of them are clinically obese which is defined by BMI greater than or equal to 30. Moreover, childhood obesity is already epidemic in some areas and on the rise in others. Around 22 million children under five are estimated to be overweight worldwide.

23

Obesity in Hong Kong 3.4 The severity of the problem of obesity in Hong

Kong has not yet reached that in developed countries such as the US. Table 3.1 shows the percentage of overweight and obesity in Hong Kong from a local study conducted in 1995 to 1996.29 The prevalence of overweight and obesity was also found to increase with age in women. Nearly 50% of women aged above 45 were overweight and nearly 10% of them were obese. For men, however, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was similar among different age groups.

3.2 The prevalence of obesity is rising rapidly in

developed countries. In the US, the UK and Japan, the prevalence of adult obesity has nearly doubled or even more since the 1980s. 2;24-26 A similar trend is also seen in adolescents.27-28

3.5 A telephone survey commissioned by the

Department of Health (DH) was conducted in early 2003 to assess the prevalence of overweight and obesity, as well as related health behaviours. Among 1,700 subjects aged 20 to 64, 19.7% of men and 13.8% of women were overweight, while 23.4% of men and 12.7% of women were obese (Table 3.2).30 While the prevalence of overweight and obesity are higher than that of the study described in paragraph 3.4,29 it should

3.3 In general, obesity is more prevalent in urban

than in rural areas. In developing countries, obesity is more common in people of higher socioeconomic status and in those living in urban areas. In developed countries, it is common in people, especially in women, of lower socioeconomic status, and among people living in rural areas. Table 3.1

2

Prevalence of obesity by gender in Hong Kong, 1995-199629 BMI (kg/m2) < 20 20 - 25 25.1 - 30 > 30 Male 9.2% 52.8% 32.6% 5.4% Female 12.9% 53.4% 26.7% 7.0%

Classification Underweight Normal Overweight Obese

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

12

How common is obesity?

be noted that the study conducted in 19951996 was based on actual measurements. The survey conducted in 2003 collected selfreported values for height and weight. The cutoff points for defining weight status differed between the two studies as well.

the obesity prevalence (BMI 30.0) in both sexes (males 22.3%, female 20.0%).31

3.7 The same study showed that the prevalence of

overweight and obesity generally increased with age (Chart 3.1). In males, the problem was most prevalent among those aged 55-64 (55.4%), followed by those aged 45-54 (52.7%) and 35-44 (51.2%). In females, the prevalence was highest among those aged 55-64 (53.9%). The prevalence decreased for both males and females who are aged 75 and above. However, as mentioned in section 1.10, the reduced lean muscle mass in elderly may lead to underestimation of the degree of overweight.31

3.6 The Population Health Survey 2003/2004

commissioned by the Department of Health (DH) estimated that 17.8% of the population aged 15 and above were overweight and 21.1% were obese (Table 3.3). Overall, overweight was more common among males than females (20.1% vs.15.9%). Similar trend was found for Table 3.2

Prevalence of obesity by sex in Hong Kong, 2003 (self-reported data)30 BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 18.5 - 22.9 23.0 - 24.9 Above 25.0 Male 8.2% 48.7% 19.7% 23.4% Female 15.8% 57.7% 13.8% 12.7% Overall 12.5% 53.7% 16.4% 17.4%

Classification Underweight Normal Overweight Obese

Table 3.3

Prevalence of obesity by sex in Hong Kong 2003/2004 (provisional data)31 BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 18.5 - 22.9 23.0 - 24.9 Above 25.0 Male 7.8% 46.8% 20.1% 22.3% 3.0% Female 12.4% 48.8% 15.9% 20.0% 2.9% Overall 10.3% 47.9% 17.8% 21.1% 3.0%

Classification Underweight Normal Overweight Obese Unknown/ missing

13

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

How common is obesity?

Chart 3.1

Prevalence of obesity (%)

60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0%

Prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI 23) by age group and sex in Hong Kong, 2003/200431

Female Male Total

15-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-64

65-74

75+

Age (Years)

Chart 3.2

Prevalence of childhood obesity

25%

Prevalence of childhood obesity in primary schools by gender and school year in Hong Kong, 1997-200232

Male

20% 15% 10% 5%

Female Total

0%

97/98

98/99

99/00

00/01

01/02

Year

Chart 3.3

Prevalence of childhood obesity

25%

Prevalence of childhood obesity in secondary schools by gender and school year in Hong Kong, 1997-200233

Male

20% 15% 10% 5%

Female Total

0%

97/98

98/99

99/00

00/01

01/02

Year

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

14

How common is obesity?

3.8 The Student Health Service of the DH found

that the prevalence of obesity among local pr imary and secondary school students increased gradually from 12.1% in 1997/1998 to 14.1% in 2000/2001, and dropped slightly afterwards using the definition of obesity as having a weight > median weight for height x 120%. The problem was more serious in primary school students than in secondary school students. The prevalence remained higher among boys with the difference between boys and girls widening slightly over the years (Charts 3.2 and 3.3).

32-33

of males and 9.8% of females had diabetes mellitus (either already on medication to treat diabetes or had a glucose level 11.1mmol/L after a 75g oral glucose tolerance test); another 14.2% of males and 17.1% of females had impaired glucose tolerance which was an early sign of diabetes mellitus (plasma glucose level two hours after the 75g glucose load was in range 7.8-11.0mmol/L).29

Dietary Habits and Physical Activity of Hong Kong People

Dietary habits

Obesity Related Diseases in Hong Kong 3.9 The majority of obesity-related diseases are

multi-factorial. Given the strong association between increasing BMI and type II diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, it is reasonable to attribute a significant proportion of these diseases to obesity.

3.12 Healthy Living Survey 2001 found that only

21% of adult respondents consumed fresh fruit at least twice a day and only 49% consumed vegetables at least twice a day. The mean quantity of daily fr uit and vegetable consumption for those who ate fruit or vegetable at least once a day was 1.4 fruit and 1.2 bowls. Only 3% of respondents consumed high-fat food at least once a day and 10% ate all visible fat in their food.35

3.10 Heart diseases (coronary heart disease being the

major component) and cerebrovasular diseases account for 14.6% and 9.5% respectively of the total deaths in 2003 in Hong Kong.34

3.13 A telephone survey commissioned by the DH

in 2004 estimated that the daily average consumption of fruits and vegetables was 3.3 servings per person and less than one in five (17.7%) of respondents reported consuming five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day. Females (21.3%) were more likely than males (13.8%) to consume five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day. In females, the proportion who consumed five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day

3.11 A local prevalence study of 2,800 adults aged

25 to 74 in 1995/1996 found that 1 in 10 men and 1 in 9 women had definite hypertension (systolic blood pressure (SBP) 160mm/Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 95mmHg), and 1 in 12 men and 1 in 16 women had borderline hypertension (SBP 140-159mm/Hg and/or DBP 9094mmHg). The study also found that 9.5%

15 Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

29

How common is obesity?

increased with age, from 15.2% for those aged 18-24 to 38.2% for those aged 55-64. In males, the proportions were the lowest in the 35-44 age group and the highest for those aged 55-64 (11.2% and 17.3% respectively).

36

3.16 The Population Health Survey in 2003/2004

commissioned by the DH estimated that 33.3% of the Hong Kong population aged 15-64 (33.0% for males and 33.5% for f e m a l e s ) we re p hy s i c a l l y i n a c t ive. Comparatively, the 25-34 age group was the mostly sedentary age group (37.9%), followed by the 35-44 age group. Analyzed by occupation, the mostly sedentary occupation was clerks (42.8%).31 The recommendation for individuals to accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on most days is largely aimed at reducing cardiovascular diseases and overall mortality.The amount needed to prevent unhealthy weight gain is uncertain. Recommendation made by consensus during two international conferences stated that about 45 to 60 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity is needed on most days or every day to prevent unhealthy weight gain.37

Low intake of fruits and vegetables is estimated to cause about 19% of gastrointestinal cancers, 31% of ischaemic heart disease and 11% of stroke worldwide. The WHO recommends 400 g daily intake of fruits and vegetables for adults per day for the prevention of chronic diseases such as heart diseases, cancer, diabetes and obesity.37 Physical activity

3.14 In Hong Kong, sedentary lifestyle is prevalent

among the local population and television viewing is a very popular pastime. A survey found that more than 80% of children watched TV at leisure time, while only 33% chose to exercise.38 Moreover, nearly half of the children (45%) watched TV for over 3 hours per day. In 2001, Hong Kong people on average spent 2.4 hours daily on watching television,35 although this figure is 18 minutes less than that noted in 1999.39

3.15 A survey conducted in 2001 found that 55%

of local adults had done exercise within the previous month. Around 40% and 12% of these respondents exercised 1 to 7 times and 8 to 11 times respectively within the preceding month for duration of over 30 minutes each time.35 Another study conducted in 2001 showed that children in Hong Kong exercised less than those in other developed countries.40

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 16

Chapter 4 Who are at risk?

4.1 Obesity results from an imbalance between

energy intake and energy expenditure. Energy derived from food is used to sustain body mass, to fuel metabolic functions and to perform physical activity. When we take in more dietary energy than we can consume, the excess is stored in the body as fat.

members of the same family also share the same diet and similar lifestyle which contribute to obesity. Ethnic origin

4.5 Certain ethnic groups are more susceptible

to the development of obesity and its complications, and the effects become apparent when the individuals are exposed to a more affluent lifestyle. For the majority, t h i s p ro bl e m s e e m s t o re s u l t f ro m a combination of genetic tendency and a change from a traditional to a more affluent and sedentary lifestyle and its accompanying dietary pattern.2 Biological factors may help to explain why obesity occurs in certain individuals but not the others. These irreversible factors are relatively less important than the reversible ones such as nutrition and physical activity, from the health promotion point of view.

Biological Factors

Age

4.2 In general, obesity in both sexes becomes more

prevalent as age increases up to at least 50 to 60 years old. The older population has a higher tendency of being overweight or obese because of the decreased lean muscle mass, metabolic rate and physical activity that occur along with the ageing process. Sex

41

4.3 Women generally have higher rates of obesity

while men have higher rates of overweight. It is widely recognised that women usually have a higher percentage of body fat and a lower resting metabolic rate than men, which may predispose women to obesity. The difference of obesity prevalence in women and men may also be attributed to their difference in hormonal regulation and fat metabolism which are not fully understood. Genetic susceptibility

2

Nutrition 4.6 Modern diet has changed from one consisting

of more complex carbohydrates, whole grains and fibres to one with high animal fats and proteins, refined carbohydrates, sugars and few fruits and vegetables.

4.4 Obesity tends to run in families. The risk of

developing obesity is one- to two-fold for the first-degree relatives of an overweight person, and about two- to three-fold for those of an obese person.42 While genes influence weight,

4.7 Taking into account all developing countries,

the per capita consumption of meat and dairy products rose by an average of 50% per person between 1973 and 1996.43 Traditional cuisines and homemade food are increasingly saving

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 18

Who are at risk?

naturally present in honey, syrups and fruit juices, increase the energy density of diet without providing much specific nutrients and result in a positive balance of total energy intake. In the expert consultation commissioned by the WHO, and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2003, a set of guidelines was developed as population nutrient intake goals for the prevention of diet-related chronic diseases replaced by high-fat, energy-dense fast foods and soft drinks. such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes and obesity. One recommendation is that consumption of free sugars should not exceed 10% of total energy intake.37

4.8 People choose energy-dense, nutr ientpoor fast foods because they are cheap, t a s t y, w i d e l y p ro m o t e d a n d r e a d i l y available. Energy-dense foods tend to be high in fat (such as butter, oil and fr ied foods), sugar or starch, while energydilute foods have high water content (such a s f r u i t s a n d ve g e t a b l e s ) . T h e r e i s convincing evidence that a high intake of energy-dense foods induces weight gain, whereas a high dietary fibre intake helps protect against weight gain. 37

4.10 Eating habit has a bearing on the development

of obesity. Skipping breakfast may lead to over-consumption later in the day.44 Besides, those who eat out more, on average, have a higher BMI than those who eat at home more often.44-45

Physical Activity 4.11 Studies have revealed an inverse relationship

between BMI and physical activity. 46-49 People in developed countries lead a more sedentary lifestyle because of increasing use of public transport coupled with affordability of cars, automation of work, use of labour-

4.9 There are evidences suggesting that free sugars,

which are defined as sugars added to foods by manufacturer, cook or consumer, plus sugars

19

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions Who are at risk?

devices both at home and at work, and more sedentary leisure pursuits such as TV viewing.

50

activity patterns have overwhelmed our bodys regulatory processes that keep weight stable in the long term. Obesity is not just a problem of the individual. It is a population problem and should be tackled as such.

The global estimate for the prevalence of

physical inactivity among adults is 17%. Estimates for prevalence of some, but insufficient physical activity (<2.5 hours per week of activities of moderate intensity) range from 31% to 51%.

51

4.12 It is suggested that a total of one hour per

day of moderate intensity activity, such as brisk walking, on most days of the week is needed to maintain a healthy body weight, particularly for people with sedentary occupations.

42

Micro-environments

Home environment

4.15 The home environment is the most important

setting in shaping childrens eating behaviours and physical activity patterns which may promote the development of obesity. It has been shown that food consumption by children is influenced by the food availability and accessibility, parents nutr ition knowledge, attitudes and practices, TV viewing and child-parent interactions concerning food. For example, using foods as rewards and restricting access to foods

Regular exercise raises the resting metabolic rate.52 People who perform regular moderate levels of physical activity increase their capacity to utilise fat.53

Environmental Factors 4.13 The rapid increase in obesity rate over recent

years has occurred in too short a time for significant genetic changes to take place within populations. This suggests that the rapid global rise in obesity is likely attributable to a changing environment that causes overconsumption of food and promotes a sedentary lifestyle.

increase childrens preferences for and intake of those foods.54-57

4.14 Environmental and social factors exist to

influence individual lifestyle and behaviours. Their effects on food intake and physical

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

20

Who are at risk?

School environment

TV advertisement

4.16 Schools are the key setting for influencing

childrens behaviour. Hence, tackling obesitypromoting elements in schools is important to prevent childhood obesity. For example, soft drink vending machines are increasingly available in schools. A study has shown that excessive consumption of high-sugar soft drinks is associated with obesity in children. Fast food restaurants

58

4.18 Fast food restaurants and energy-dense foods and

drinks are among the most advertised products on television. These commercials are often targeted at children. M o r e ove r, t h e amount of TV viewing was associated with childrens demand for the highly advertised foods.60

4.17 Fast food outlets which provide high-fat,

energy-dense foods and soft drinks are increasingly popular throughout the world. An average fast food restaurant meal provides 1,000-2,000 kilocalories, i.e., up to 100% of the recommended daily intake for adults, and the portion size is also increasing. advertising and low price.

59

Macro-environments

Socio-economic environment

4.19 Obesity is more prevalent in individuals with

high socio-economic status (SES) in developing countries than individuals with low SES in developed countr ies. In developed countries, high SES protects people from becoming obese as these individuals are better educated and live in less obesity-promoting environment with more physical recreational facilities and less fast food outlets.61 They are thus more likely to follow dietary guidelines, eat healthily and engage in physical activity. Urbanisation

Their

popularity is further enhanced by mass

4.20 With urbanisation, food is more abundant and

TV penetration is increased. With more women working, the demand for high-fat, energy-dense and low-nutrient ready-to-eat food and labour-saving devices such as washing machine is increased. Also, less time

21 Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions Who are at risk?

is allocated to cooking. All these have profound effects on the dietary habit and physical activity level of the population. Cultural environment

in the last three decades. A slim figure in women has come to symbolise competence, success, control and sexual attractiveness, while obesity represents laziness, selfindulgence and a lack of will power.2 These values are reinforced by television and popular magazines 62-63 that lure people to adopt unhealthy weight control practices such as inappropriate dieting, which very often results in weight cycling, eating disorders and failure to achieve weight goals.64-66 Men do not generally recognise being overweight or obese as a problem. This phenomenon raises concern because men are more at risk of abdominal fat accumulation and yet tend to ignore it.2

4.21 Throughout most of human histor y,

increased weight has been viewed as a sign of health and wealth. This is still the case in many cultures, especially where conditions make it hard to gain weight or where thinness in babies is associated with increased risk of infectious diseases.2

4.22 On the other hand, in many industrialised

countries, there has been a marked change in the expectation of body shape and weight

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

22

Chapter 5 Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.1 This section will discuss the initiatives which

aim at preventing overweight and obesity mainly through lifestyle measures, chang ing environment and setting policy. Literature review was conducted by means of EBSCO research database. Initiatives quoted in several obesity prevention review papers are also included in this section. Both initiatives either with or without BMI/body weight change as the outcome measurements are covered. For example, studies aiming at increasing intake of fruits and vegetables and decreasing sedentary activities are also included. However, specific treatments for obesity (e.g., drug treatment, surgical treatment) are excluded. A life-course approach is adopted to summarise the initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity. growth and development of infants. 67 It is recommended that inf ants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life to achieve optimal growth, development and health.68

5.5 There is growing evidence suggesting that

breastfeeding can prevent subsequent childhood overweight and that longer breastfeeding period gives greater protection for children though the mechanism of this protection is not clear.69-72 Besides, breastfeeding has a lot of other benefits to mothers and children. The continued protection, promotion and suppor t of breastfeeding remain a major health priority.

5.6 The US Government has included breastfeeding

as a key objective in its national prevention agenda - Healthy People 2010. The agenda aims to attain a breastfeeding rate of at least 75% during early postpartum period, 50% at 6 months and 25% at 1 year by 2010.73

Infancy 5.2 Infancy is an important stage of growth and

development. During infancy, nutrition is the most important factor that affects growth of infants. Therefore, this stage plays a key role in controlling obesity. The level of physical activity of infants should normally be within a limited range.

5.7 Three types of initiatives have been shown to

be useful in promoting breastfeeding when delivered as a single initiative. They include small group health education, peer support programmes and one-to-one health education. Packages of initiatives have also been shown to be effective at increasing the initiation and, in most cases, extending the duration of breastfeeding in developed countries. Effective packages include a peer support programme and/or a media campaign combined with policy changes in the health sector.74

5.3 Infancy is also a stage of dependency. Parents

and carers are the key providers of nutrition for infants. Hence, it is important that they choose suitable food for infants in order to maintain their normal growth and development. Breastfeeding

5.4 The WHO recommends breastfeeding as the

way of providing ideal food for the healthy

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

24 25

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.8 The WHO and the United Nations Childrens

Fund (UNICEF) launched the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in 1991 as a key strategy for promoting breastfeeding.75 Under the BFHI, hospitals and maternity facilities can be designated baby-friendly when they do not accept free or low-cost breastmilk substitutes, feeding bottles or teats, and have implemented the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (Table 5.1).

76

5.9 Breastfeeding rate in Hong Kong is still relatively

low but a rising trend has been noted since 1991.78 A local study found that from 1987 to 1997, the breastfeeding initiation rate increased by 6.7% (from 26.8% to 33.5%).79 Moreover, the rate of breastfeeding for more than 3 months increased from 3.9% in 1987 to 10.3% in 1997. Annual breastfeeding surveys conducted by the DH reveal that both the prevalence and the duration of breastfeeding in Hong Kong have increased since 1997. The percentage of babies ever breastfed increased from 50% in 1997 to 62% in 2000.78

Moreover, the WHO and the

UNICEF have jointly developed the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes to guide appropriate marketing practices and to protect breastfeeding (Table 5.2).77 Table 5.1 Ten steps to successful breastfeeding76

Every facility providing maternity services and care for newborn infants should: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff. Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy. Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding. Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within half an hour of birth. Show mothers how to breastfeed, and how to maintain lactation even if they should be separated from their infants. Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicated. Practise rooming-in - that is, allow mothers and infants to remain together - 24 hours a day. Encourage breastfeeding on demand. Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants. from the hospital or clinic.

10. Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge

25

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

Table 5.2

Summary of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes77

The Code includes these 10 important provisions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. No advertising of all breastmilk substitutes* to the public. No free samples to mothers. No promotion of products in health care facilities, including no free or low-cost formula. No company representatives to contact mothers. No gifts or personal samples to health workers. Health workers should never pass products on to mothers. No words or pictures idealizing artificial feeding, including pictures of infants, on the labels. Information to health workers must be scientific and factual. All information on artificial infant feeding must explain the benefits and superiority of breastfeeding, and the costs and hazards associated with artificial feeding. Unsuitable products, such as sweetened condensed milk should not be promoted for babies. not acted to implement the Code.

* Breastmilk substitutes include: infant formula, follow-up formula, feeding bottles, teats, baby food and beverages etc.

10. Manufacturers and distributors should comply with the Codes provisions even if countries have

5.10 Various efforts have been made to promote

breastfeeding in Hong Kong. Since the early 1980s, a designated team has been set up by the former Medical and Health Department to promote breastfeeding. Promoting work includes running antenatal classes at Maternal and Child Health Centres and public hospitals for expectant mothers, visiting postnatal wards and providing counselling and active support for those who chose to breastfeed. In 2000, the Family Health Service of the DH formalised the existing breastfeeding guidelines into a written breastfeeding policy.80 The main points in the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes have been incorporated into the policy. In support of the annual World Breastfeeding Week (1st to

7th of August), the DH organised a publicity campaign to raise public awareness of breastfeeding in 2003 and 2004 (Diagram 5.1 and 5.2). Diagram 5.1 An advertisement of promoting breastfeeding in MTR station in 2003

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

26

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

Diagram 5.2 Promoting breastfeeding - Baby Expo 2003

dur ing childhood and adolescence is associated with obesity in adulthood. 82-83 A study reported that obese children will have a risk as high as 80% of developing adult obesity (BMI > 28) when they are 35 years old. 84

5.13 School-based programmes for obesity

prevention are attractive for several reasons, including the large amount of contact time with school children; the utilisation of the existing organisational, social and communication structures; and the ability

Childhood and Adolescence 5.11 Childhood and adolescence are the stages of

maximal physical development. Both nutrition and physical activity are crucial for normal development, as well as the prevention of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Unlike infants, the nutritional intake of children and adolescents is only partially controlled by their parents. Many of them purchase snacks and lunch themselves. Thus, health education is important to increase their knowledge and alter their attitudes towards healthy eating. On the other hand, nutritional adequacy for normal growth and development must be ensured in any childhood obesity prevention effort.

81

to reach a large percentage of children in the population at a low cost.85 There have been controversies about banning the sale of unhealthy food and drinks in schools. However, increasing the availability of more healthy food and dr inks in schools, especially at lower prices, could be an alternative.86

5.14 Many school-based obesity preventive

prog rammes do not target at obesity specifically but rather at reducing risk factors of non-communicable diseases (NCD) such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Such programmes focus on improving diet and increasing physical activity level in general. These initiatives generally include classroom components that teach students about and motivate them to acquire healthier habits.87-100 These programmes are usually successful in increasing healthy behaviours such as physical activity and consumption of fruits and vegetables.

5.12 BMI begins to increase rapidly after a period

of reduced adiposity during preschool years. Children at the age of around 5 to 7 will easily get fat, a phenomenon known as adiposity rebound.

27

2

Moreover, obesity

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.15 Although obesity is common among school

children, it is not considered to be a top priority in the school agenda. The issue of obesity has to compete with many other health issues, such as anti-smoking, sexuality and other non-health topics including environmental protection, fire safety, etc.

101

three mechanisms: (1) reduced energy expenditure due to the displacement of physical activity by TV viewing, (2) increased energy intake from eating during viewing or consuming extra food bought after watching food advertisements, and (3) decreased resting metabolic rate during viewing.105

5.16 The concept of health-promoting school is

an extension of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion initiated by the WHO in 1986. In a health-promoting school, students are encouraged to enjoy healthy school life, promote healthy living in their families and communities, and protect their own health.

102

5.18 Two school-based programmes aiming at

reducing the amount of time spent on sedentary behaviour showed a consistent and sizable decrease in TV viewing among children. One of these programmes showed a significant decrease in the participants BMI, skinfold thickness, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio, 106 while the other showed a 24% reduction in the prevalence of obesity among girls but no change among boys. 107 These prog rammes included instructions in behavioural management techniques or strateg ies such as selfmonitoring of viewing behaviour, limiting access to TV and video games, and limiting the time for watching TV and playing video games. M o re ove r, l e s s o n s o n s e l f monitoring and reduction of TV and video

Different health education and promotional activities on various health topics, including healthy lifestyles, are organised by the school to create a healthy school environment that facilitates the healthy development of students. For example, a large-scale health promotion campaign called The Biggest Healthy Breakfast Day was organised in 2002 to promote healthy eating habit to students, parents and teachers.103 School-based programmes to reduce sedentary activities

game usage were incorporated into the c u r r i c u l u m f o r s t u d e n t s . Pa re n t a l involvement was also a prominent part of the programme. Newsletters that were designed to motivate parents to help their children adhere to their time schedules and provide suggested strategies for limiting TV, videotape and video game use for the whole family were distributed to parents.106

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 28

5.17 Wa t c h i n g T V i s t h e m o s t c o m m o n

sedentary activity of children, which is one of the most modifiable causes for obesity in children. Young people have become more physically inactive in the last 30 years, largely because they spend much time watching TV.

104

TV viewing is believed to

have caused obesity by one or more of the

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

School-based programmes on physical education (PE)

project, rope skipping, etc). The DH has also promoted physical activity in kindergartens through the use of kid songs. Short-term results showed that over 60% of children continued to exercise 20 minutes each day for at least 20 days after the programme.116 School-based programmes on dietary modification

5.19 School-based PE programmes promote physical

activity by modifying curricula or policies in schools. These programmes increase the amount of time students spent on moderate and/or vigorous activities. This can be done in a variety of ways, including having more PE classes, lengthening existing PE classes, or increasing the intensity level of physical activity of students dur ing PE classes without necessar ily lengthening class time. 108 Some schools encourage extracurricular activities such as sports days and outings to increase physical activity time and levels among students.

5.22 Many school-based programmes advocate

healthy eating as a means of preventing obesity. Increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables, and decreasing the amount of fat intake have been the main aims of many programmes. The WHO recommends that the consumption of fruits and vegetables be increased for both adults and children. Adults and children should consume at least five servings of fruits and vegetables each day (for the definition of one serving size of fruits and vegetable, see Table 5.3).117 However, the adoption of the recommended standard by the American children and adolescents has been unsuccessful. A study showed that among American children aged 6 to 11, only 16% of them ate 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day.118 Table 5.3 Definition of one serving size of fruit and vegetable119

5.20 There is strong evidence that school-based

PE is effective in increasing levels of physical activity and improving physical fitness among students. However, BMI measurements mostly show small decreases or no change.109-115 The varied results may be due to limited efforts being put on dietary education.115 However, increasing physical activity levels can bring about many benefits, such as reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and certain forms of cancers, and improving musculoskeletal health.

5.21 Compared with other countries where daily PE

classes are recommended, primary schools in Hong Kong generally allocate only two 35minute lessons per week to PE. To fill the gap, the Education and Manpower Bureau (EMB) and other organisations have organised many school-based physical activity programmes (e.g., morning exercise, comprehensive dance

29 Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

One medium fruit (e.g., apple, orange, banana, pear) 3/4 cup (6 oz.) 100 percent fruit or vegetable juice 1/2 cup cut-up fruit 1/4 cup dried fruit (e.g., raisins, apricots, mango) 1 cup raw, leafy vegetables 1/2 cup raw or cooked vegetables 1/2 cup cooked or canned peas or beans

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.23 Educational programmes on nutrition have

been implemented worldwide and are successful in increasing the knowledge of healthy eating among students. Changes in attitude and behaviour are noted.

120-122

s c h o o l s a n d H e a l t hy L u n c h We e k Competition in secondary schools were conducted by the DH to promote healthy eating among students. The programmes aimed at increasing the knowledge of healthy eating among teachers, parents, students and tuckshop operators, and improving the availability of healthy food in schools.124-125 All of the three movements were co-organised with non-governmental organisations (NGO) and academic institutions. Healthy eating was promoted through various channels, e.g., pamphlets, posters, exhibitions, health talks, etc. Parents, teachers and tuckshop owners were involved. A teaching kit was developed for each healthy eating movement to facilitate sustainability of the programme in schools.124-125 Similar programmes were also conducted in kindergartens and nurseries to promote healthy birthday parties. All of these healthy eating programmes had favourable short term results in improving the knowledge of children, but they did not show any behavioural change in the eating habits of children.126

5.24 School-based programmes aimed at educating

students to reduce intake of carbonated drinks were shown to be effective. A cluster randomised controlled trial conducted in the UK found that consumption of soft drinks was reduced among the students by an educational programme to discourage them from consuming carbonated dr inks. Moreover, the percentage of overweight and obese children decreased in the intervention group, compared with an increase in control group.123

5.25 Similar programmes have been tried out in

Hong Kong. Three movements, namely, H e a l t h y E a t i n g M ove m e n t f o r kindergartens/nurseries (Diagram 5.3), Healthy Tuckshop Movement in primary

Diagram 5.3 Healthy Eating Movement for kindergartens and nurseries in 1999

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

30

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.26 The EMB has incorporated teaching of

healthy eating into the school curriculum. In primary schools, knowledge and correct attitudes towards healthy eating are taught in the General Studies curriculum. The teaching becomes more advanced in secondary schools. In addition to learning the importance of a balanced diet in the classes of biology, social education and home economics, students also explore the issue of obesity in their science and technology subjects.

verbal advice, written materials, assessment, etc.) concluded that the effect is uncertain.127 It was suggested in the review that singlefacet initiatives targeted to patients in primary care to address physical activity alone could not achieve significant results. The programmes had to be incorporated into multi-faceted, community-wide strategies to become effective. However, examples to elaborate on details of such strategies were not included. Exercise prescription (Diagram 5.4) is a piece of advice on physical activity prescribed by doctors to patients, like medication prescription. It clearly indicates the type, frequency and duration of exercises that the patient needs to do. Diagram 5.4 An example of exercise prescription prescribed by doctors

Adulthood 5.27 Adulthood is a stage in which growth has been

stabilised and degeneration gradually sets in, especially in late adulthood. Caloric intake needs to be reduced as metabolic rate decreases. In Hong Kong, adults are often occupied with work and lack time for regular exercise. According to the 2001 Healthy Living Survey, around 45% of the respondents had not exercised for at least 30 minutes in the month before the study took place.35 This lifestyle predisposed them to obesity. Promoting physical activity in primary care settings

5.28 Doctors working in primary care settings are

ideally placed to provide health education to the general adult population. They have the opportunity to inform and influence patients on measures that enhance health at a time when patients are generally receptive to health advice dur ing medical consultation. However, a systematic review of the initiatives to promote physical activity in primary care settings (including exercise prescription,

31 Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.29 A randomised controlled trial on exercise

prescription was conducted in 2003 by the DH. General practitioners were recruited from government and private clinics to participate in the study. The results showed that exercise prescription brought about significant changes in stage progression in Prochaskas Stages of Change Model. However, concomitant changes in physical activity levels were not noted. This indicates that the intervention could have an impact to motivate sedentary patients to exercise but the intensity is not strong enough to bring about a change in physical activity level. Developing methods to reinforce the programme used in this study is a future challenge. Reinforcement can be provided by a conducive environment for the patients to exercise or following up the exercise prescription recommendations by d o c t o r s i n s u b s e q u e n t m e d i c a l consultations. Tailor-made physical activity programmes

Workplace initiatives on physical activity and/or dietary modification

5.31 Workplaces are ideal community settings to

implement health promotion initiatives. They offer not only the ready access to a large proportion of the adult population who spend over half of the day there, but also the use of existing organisational structures for delivering these initiatives.133

5.32 Workplaces initiatives to promote physical

activity are generally about providing easy access to facilities (e.g. gymnasium) where people can do exercise. 134-135 They also provide training and health education to participants. 136-140 These programmes are effective in getting people to exercise more. O t h e r wo r k s i t e i n i t i a t ive s p rov i d e comprehensive health promotion activities to target behavioural risk factors such as low level of physical activity and unhealthy diet. The prog rammes mainly consist of workshops, educational classes, support g ro u p s , e x h i b i t i o n s a n d s o m e t i m e s environmental modifications. These programmes can effect a positive change of lifestyle habits. Promoting physical activity using social support initiatives

5.30 Tailor-made physical activity programmes are

designed to suit each participants interests and preferences, and incorporate physical activity into daily routines. Programme components usually include skills such as goal-setting and self-monitoring of progress towards the goal.

128-132

5.33 Programme sustainability is an important

consideration for effective promotion of physical activity. This can be achieved through social support, which is defined as the presence of interpersonal liking, attraction and group cohesiveness among individuals exercising together. Initiatives of social

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 32

These programmes are generally

effective in increasing physical activity level among both men and women, and in a variety of settings.108 A decrease in body weight128 or percentage of body fat some studies.

132

was reported in

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

support include making a contract with other participants to achieve specified levels of physical activity or setting up walking groups to provide companionship and support. Project staff will also phone participants to monitor prog ress and encourage continuation of activities.108

adults. Despite this, many old people remain active and enjoy a good quality of life.

5.37 The 2001 Healthy Living Survey found that

compared to younger adults, more older people had exercised in the month prior to the study.35 Older people had a participation rate of 63.5%, which was higher than that of people aged 40 to 49 at 45.3%.

5.34 Most social support initiatives are effective in

getting people to become more physically active. 141-145 The programmes enhance participants fitness levels, knowledge about exercise and confidence in exercising. These initiatives are effective in various settings and among adults of different sexes, ages and interests to exercise.

108

5.38 Older people usually do not engage in

vigorous exercise. Most of them prefer stretching exercise or mild aerobic exercise, such as morning walks and Tai Chi. These exercises provide an opportunity for social gatherings as well as benefiting their health. To prevent obesity in elderly, physical activity plays an equally important role as nutrition. Nutritional education classes

Commercial services or products for weight control

5.35 There are many commercial companies in

Hong Kong providing a range of services and products for slimming and maintaining fitness. Slimming has become a popular trend in recent years. Many slimming or beauty centres have been established in Hong Kong. They claimed that they help clients reduce weight in a very short period of time. However, most of these services and products lack scientific evidence for their effectiveness in weight loss or weight control.

5.39 Group nutritional education classes are

commonly held in different settings, such as elderly centres, clinics, etc. Many elderly acquire nutritional knowledge through these classes. These classes provide a social environment for the elderly, where their problems can be shared and addressed collectively. However, effects of nutritional programmes on older people are inconclusive. For dietary practices, one study showed no significant improvement,146 while another study showed improvement in the short term though the effects were not maintained at the 6-month interval.147 However, there are no standardised instruments currently available that assess eating behaviours and nutrition knowledge in older adults.

Old Age 5.36 From a physiological perspective, old age is

the stage of degeneration. Because of the physiological changes associated with aging, elderly usually have slower and much more restricted range of movements than younger

33 Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

5.40 The Elderly Health Services of the DH often

organise health talks and support groups for the elderly. Some of these activities are organised in collaboration with other community service units. The objectives of the health talks are to motivate elderly to adopt healthy lifestyles and to increase their health knowledge on common health problems such as weight control. Support groups for weight reduction and healthy eating are also organised.

Physical activity groups (morning walk)

5.41 Morning walk is popular in Hong Kong.

Every morning, there are hundreds of small to large groups of people (usually elderly) gathering to do exercise. These groups are organised by government organisations and NGOs, or initiated by the group members themselves. The types of exercise they do are mostly stretching exercises of mild to moderate intensity (e.g., Tai Chi). There are successful overseas examples which have increased the physical activity level (especially for walking) among the elderly by using programmes such as walking training sessions and personal reinforcement by telephone follow-up.148-149

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

34

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

General (all age)

Point-of-decision prompts to promote physical activity

loss rather than to health benefits. However, the effects were mainly short-term. The percentage of people using stairs dropped when the prompts were removed.150

5.42 Point-of-decision prompts are signs placed

near escalators and elevators to encourage people to use stairs for health benefits or weight loss. This programme is shown to be effective in various settings including subways, train and bus stations, shopping malls, university libraries, and among various population subgroups including men and women, both obese and not obese. 150-154 Studies showed that point-of-decision prompts were effective in increasing the level of physical activity, as measured by an increase in the percentage of people choosing to use the stairs. More people would use the stairs when these signs were posted. Tailor-made prompts to describe specific benefits or to appeal to population subgroups may increase the initiatives effectiveness. For example, one study found that obese people used the stairs more if the signs linked stair use to weight

5.43 In 2003, the DH launched a point-ofdecision prompts pilot programme to promote stair use in selected public housing estates (Diagram 5.5). Twelve blocks were selected for the study, in which 9 were assigned as the intervention group and the remaining 3 as the control group.The results showed that the stair utility of the intervention group increased from 2.9% at the baseline level to 3.5% 3 weeks after the implementation of the programme. The increment was significant when compared to that of the control group. Moreover, a survey found that both environmental and personal factors were cited as the major enabling and disabling factors for the respondents to use the stairs.155

Diagram 5.5 Posters and stickers of point-of-decision prompts in public housing estates

35

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions

Initiatives to prevent overweight and obesity

Community-wide campaigns to reduce risk factors of noncommunicable diseases (NCD)

Campaign in 2000 to promote regular exercise to the public. This campaign comprised both health education and a mass media publicity programme.

5.44 Over the last 20 years, several large-scale,

community-wide and multi-component programmes aiming at reducing the risk factors for NCD like cardiovascular diseases were conducted in many developed countries including the US, Denmark, Finland, and so on. 156-162 The initiatives used in these programmes adopted a multidisciplinary approach and required multisectoral collaboration. Campaign messages were disseminated through mass media including TV, radio, newspaper, mails , billboards and advertisement to reach the target population. Results showed that these campaigns were successful in increasing the level of physical activity of participants and changing their diet towards healthy eating.

5.47 In 2001, 55% of the respondents of the

Healthy Living Survey reported to have exercised in the month prior to the study. This figure is significantly higher than that found in 1999 (47%).35 However, whether the increase is related to the campaign cannot be ascertained.

5.48 The DH has also conducted other physical

activity campaigns of smaller scale targeting special community groups, such as the Exercise with Your Neighbours project. The short-term results, such as increase in the proportion of active participants, were found in the campaign.163

5.45 Community-wide educational campaigns

may produce additional benefits of increasing social networking in the community. These campaigns, however, require careful planning and coordination, well-trained staff and sufficient resources for smooth implementation. Poor planning and insufficient resources generally result in illdeveloped messages and weak campaigns that are inadequate to achieve the dosage necessary to change the knowledge, attitude or behaviour of the people.

Environment and Policy 5.49 Environmental and societal changes in recent

years have improved the living standard of the population. Unfortunately, they have also brought about undesirable changes in the food supply and consumption. Nowadays fast food and snacks which are high in fat and low in complex carbohydrates are available almost everywhere in the world. A local study revealed that most of the fast food available in Hong Kong contained too much fat, carbohydrate and cholesterol.164 It is widely perceived that obesity has increased in industrialised society as people consume more fast food.2

Tackling Obesity: Its Causes, the Plight and Preventive Actions 36