Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BkRev Buchanan Reckoning

Uploaded by

Dwight MurpheyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BkRev Buchanan Reckoning

Uploaded by

Dwight MurpheyCopyright:

Available Formats

Book Review Day of Reckoning: How Hubris, Ideology, and Greed are Tearing America Apart Patrick J.

Buchanan St. Martins Press, 2007 We have often reviewed Patrick J. Buchanans books in these pages. In our opinion, he is one of the more profound commentators on the complex of problems that bedevil the United States. He was three times a candidate for president of the United States; this is his ninth book; and he is a prominent participant in public affairs shows on television. It has been no surprise to us that he did not succeed in his quest for the presidency, since it is not to be supposed that candor and perspicacity (as distinct from a mere appearance of those qualities) mix well with the need to satisfy multiple constituencies that is essential to political success. This book brings together in one place the major themes of Buchanans previous volumes. In two books, The Death of the West and State of Emergency, he examined the demographic challenge to Europe and America posed by the combination of belowreproduction birth rates and massive Third World immigration. In A Republic, Not an Empire, he flew directly in the face of the conventional wisdom that has for the most part prevailed in the United States since as far back as 1898, that America should intervene globally to rectify the worlds wrongs. In The Great Betrayal, he reasserted the traditional American position favoring protection of American jobs and industry, arguing that the ideology of free trade (and unbridled greed) in the context of todays globalization is leading to a hollowing-out of the American economy. Now, in Day of Reckoning, he examines all three together. That he is doing so wont necessarily be immediately apparent. The issues are spread over eight chapters, which flow along as if they were a series of articles (which they may have been); and although each subject receives ample discussion in itself, the book isnt structured into compartments to demarcate clearly the issues from each other. It is a good introduction to his thought (or, more appropriately, a summation), but those who wish most seriously to study the issues he raises will want to read the earlier books weve mentioned. Even though Day of Reckoning is a revisiting of important subjects Buchanan has explored before, it is not lacking in provocative new ideas. These offer much grist for thought on matters that, in themselves, might well prove explosive. The issues deserve more exploration than this reviewer has given them, but Buchanans insights are worth noting. They add to the conventional discussion of American policy toward Taiwan, Iran and North Korea: : The George W. Bush administration has taken a strongly confrontational position vis a vis Iran. What Buchanan has to say will surprise many. He describes what Iran itself seeks, and what the United States wants from Iran, and then reports that it is said that,1 in 2003, after the U.S. occupation of Iraq, Tehran made, through the Swiss embassy, an offer to negotiate with the United States just such a grand bargain [granting what each side was seeking]. Buchanan quotes the editor of UPI about the Iranians offer: The bargain, as spelled out by the Iranians, offered to accept a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine,

1

Buchanan bases his discussion on it is said that. A reader will want something more solid.

to rein in Iranian support for what the United States considered terrorist groups, cooperation with the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan and against al-Quida, and to join a comprehensive security agreement with the countries of the Persian Gulf. This would include an agreement to exclude nuclear weapons In return, Iran wanted full diplomatic recognition from the United States, along with a suspension of U.S. sanctions and an agreement to drop plans for regime change. The U.S. response? Dick Cheney and the neocons vetoed it. For his part, Buchanan says such a bargain looks good today, especially if it included an Iranian agreement to renounce nuclear weapons and allow inspection of all nuclear facilities. The importance of this conclusion is grasped, of course, in light of how close the United States has come to war with Iran and of the chaotic effects such a war would have. Taiwan and South Korea are each flashpoints for possible future war. For many years, the United States has served as the guarantor of bothand it is may well be an atavism from the now long-past confrontation between the United States and world Communism that successive American governments continue their military commitment to each. In keeping with his overall view that under the present circumstances the United States should not undertake to be the policeman of the world, Buchanan would have the United States call a halt to each commitment. We cannot be committed forever to go to war to prevent Taiwan from assuming the status of Hong Kong. With regard to South Korea, he argues that half a century after the first Korean War, there is no reason U.S. troops should be the first to die in a second. North Korea is no longer a frontier province of Stalins empire. Any new conflict would be a Korean civil war in which no vital U.S. interest would be imperiled. He points out that South Korea has forty times the economy of the North and twice the population. For readers who like to examine critically the many shibboleths that can lead a country to disaster, Buchanan offers a provocative smorgasbord in his chapter on The Gospel of George Bush. He takes ideas contained in each of President George W. Bushs main speeches, and parses them for their truth-value. One is the statement that Bush made at West Point that moral truth is the same in every culture, in every time, and in every place. Buchanan says transparently, this is untrue Behind the clash of civilizations lies a clash of beliefs about moral truth. Do we not ourselves disagree, vehemently, on the morality of capital punishment, assisted suicide, premarital sex, pornography, abortion, homosexuality, war, drug use, gambling? Bush told the cadets the requirements of freedom apply fully to the entire Islamic world, but Buchanan points out that Muslims see Western tolerance of all faiths as indifference to all. To serious Muslims, religion is a deadly serious matter. He adds: Imagine the reaction among Americans if Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran, in defiant echo of President Bush, declared from the rostrum of the United Nations: The requirements of Islam apply fully to the entire Western world. Whereas Bush generalizes that successful societies limit the power of the state and the power of the militaryso that governments respond to the will of the people, and not the will of an elite, Buchanan asks whether it is not true that fifth-century Athens, the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire were successful societies. And when Bush says successful societies recognize the rights of women, Buchanan inquires: Has there ever been a greater example of hubris by a president than to lay down the essential principles for successful societies and cast into outer darkness every society that does not

resemble America after we ratified the Nineteenth Amendment and enlisted in the feminist revolution? The chapter goes through many statements such as those cited here, doing much to clear away mental cobwebs. Buchanan doesnt mention it, but one thing that strikes us about Bushs universalist pretension is how totally it clashes with the multiculturalism that is de rigueur in todays conventional thinking in the United States. So far as we know, there has been no public recognition of this contradiction. It is almost certainly true that those who preach American universalism also preach multiculturalismand do so without sensing any incongruity. Dwight D. Murphey

You might also like

- Jspes DDM Bkrev NaderDocument4 pagesJspes DDM Bkrev NaderDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Jspes DDM Bkrev NaderDocument4 pagesJspes DDM Bkrev NaderDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review, "Stalin's Secret Agents"Document7 pagesBook Review, "Stalin's Secret Agents"Dwight Murphey100% (1)

- Book Review of Ronald Coase's "How China Became Capitalist"Document9 pagesBook Review of Ronald Coase's "How China Became Capitalist"Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of John M. Pafford's "The Forgotten Conservative: Rediscovering Grover Cleveland."Document10 pagesBook Review of John M. Pafford's "The Forgotten Conservative: Rediscovering Grover Cleveland."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- A Preeminent Book On The Financial Crisis: Timothy F. Geithner's Memoir As Secretary of The TreasuryDocument20 pagesA Preeminent Book On The Financial Crisis: Timothy F. Geithner's Memoir As Secretary of The TreasuryDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- With Liberty and Dividends For All: How To Save Our Middle Class When Jobs Don't Pay EnoughDocument6 pagesWith Liberty and Dividends For All: How To Save Our Middle Class When Jobs Don't Pay EnoughDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- One Man's Fight For Stewardship and Professionalism: A Lesson in Business EthicsDocument5 pagesOne Man's Fight For Stewardship and Professionalism: A Lesson in Business EthicsDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- A Provocative Look at Robert Gates' 'Memoirs of A Secretary at War'Document13 pagesA Provocative Look at Robert Gates' 'Memoirs of A Secretary at War'Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- A Provocative Look at Robert Gates' 'Memoirs of A Secretary at War'Document13 pagesA Provocative Look at Robert Gates' 'Memoirs of A Secretary at War'Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Jared Diamond's "The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn From Traditional Societies?"Document7 pagesBook Review of Jared Diamond's "The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn From Traditional Societies?"Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Jared Diamond's "The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn From Traditional Societies?"Document7 pagesBook Review of Jared Diamond's "The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn From Traditional Societies?"Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Alan S. Blinder's "After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead," published in the Summer 2013 issue of The Journal of Social, Political and Economic StudiesDocument9 pagesBook Review of Alan S. Blinder's "After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead," published in the Summer 2013 issue of The Journal of Social, Political and Economic StudiesDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- In The Wake of Mandela: Paul Theroux's Latest Book On Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesIn The Wake of Mandela: Paul Theroux's Latest Book On Sub-Saharan AfricaDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- One Man's Fight For Stewardship and Professionalism: A Lesson in Business EthicsDocument5 pagesOne Man's Fight For Stewardship and Professionalism: A Lesson in Business EthicsDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Document9 pagesBook Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Hall and Lamont (Ed.s), "Social Resilience in The Neoliberal Era"Document5 pagesBook Review of Hall and Lamont (Ed.s), "Social Resilience in The Neoliberal Era"Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- David Stockman's "The Great Deformation"Document8 pagesDavid Stockman's "The Great Deformation"Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Jspes DDM Bkrev BairDocument5 pagesJspes DDM Bkrev BairDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book review, co-author with space physicist David Miller, of Colin Gillespie's "Time One: Discover How the Universe Began," published in the Summer 2013 issue of The Journal of Social, Political and Economic StudiesDocument12 pagesBook review, co-author with space physicist David Miller, of Colin Gillespie's "Time One: Discover How the Universe Began," published in the Summer 2013 issue of The Journal of Social, Political and Economic StudiesDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Document9 pagesBook Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review: International Center For 9/11 Studies, 2013Document6 pagesBook Review: International Center For 9/11 Studies, 2013Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review Article About Gregg Jones' '"Honor in The Dust: Lessons of The Spanish-American War."Document16 pagesBook Review Article About Gregg Jones' '"Honor in The Dust: Lessons of The Spanish-American War."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Jspes DDM Bkrev (2) CancerDocument5 pagesJspes DDM Bkrev (2) CancerDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Anne Applebaum's "Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-1956."Document10 pagesBook Review of Anne Applebaum's "Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-1956."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- JSPES DDM BkRev WilcoxRePattonDocument8 pagesJSPES DDM BkRev WilcoxRePattonDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Jspes DDM Bkrev ConfidgameDocument6 pagesJspes DDM Bkrev ConfidgameDwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Document9 pagesBook Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Document9 pagesBook Review of Peter Van Buren's "We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose The Battle For The Hearts and Minds of The Iraqi People."Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Political and Economic Studies, Pp. 397-406.)Document5 pagesBook Review: Political and Economic Studies, Pp. 397-406.)Dwight MurpheyNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Major Legal Systems in the WorldDocument5 pagesMajor Legal Systems in the WorldMuhammed Zahangir HossainNo ratings yet

- Report of Islamic Banking Product DevelopmentDocument3 pagesReport of Islamic Banking Product DevelopmenttisuchiNo ratings yet

- Al-Fauz Al-Kabir Fi Usul Al-Tafsir - The Principles of Quran Commentary by Shah WaliyullahDocument105 pagesAl-Fauz Al-Kabir Fi Usul Al-Tafsir - The Principles of Quran Commentary by Shah WaliyullahRicardo Almeida100% (1)

- In The Age of Averroes PDFDocument32 pagesIn The Age of Averroes PDFGreg LewinNo ratings yet

- HashimiyyatDocument23 pagesHashimiyyatAbbasNo ratings yet

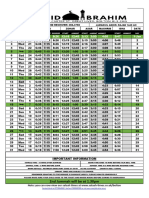

- Masjid Ibrahim 2024 TIMETABLEDocument13 pagesMasjid Ibrahim 2024 TIMETABLEj2yhspmj6cNo ratings yet

- How Did Shirk Begin and What Were The Main CausesDocument4 pagesHow Did Shirk Begin and What Were The Main Causesharoons201No ratings yet

- Making Dhikr After Prayer Boosts RewardsDocument16 pagesMaking Dhikr After Prayer Boosts RewardsdNo ratings yet

- The Andhra Pradesh Gazette: Published by AuthorityDocument3 pagesThe Andhra Pradesh Gazette: Published by Authoritybmahdi4176No ratings yet

- ملخص رسالة شرح مختصر الكرخي لأبي الحسين القدوري باللغة الإنجDocument5 pagesملخص رسالة شرح مختصر الكرخي لأبي الحسين القدوري باللغة الإنجrnharveyNo ratings yet

- Thorough Study of DemocracyDocument52 pagesThorough Study of DemocracyalenNo ratings yet

- Ruby in The DuuDocument373 pagesRuby in The DuuGaneshNo ratings yet

- 3M 2016Document32 pages3M 2016Hidup Sebelum MatiNo ratings yet

- Women's Taraweeh Prayer at Home or MosqueDocument4 pagesWomen's Taraweeh Prayer at Home or MosqueSamiha TorrecampoNo ratings yet

- The Stony Brook Press - Volume 23, Issue 3Document28 pagesThe Stony Brook Press - Volume 23, Issue 3The Stony Brook PressNo ratings yet

- World ReligionDocument1 pageWorld ReligionIsséNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Significance of Mulla Sadras Quranic Writings JIP 6 2010 109 130 PDFDocument27 pagesThe Nature and Significance of Mulla Sadras Quranic Writings JIP 6 2010 109 130 PDFSam FrostNo ratings yet

- Musannaf e Abdur RazzaqDocument82 pagesMusannaf e Abdur RazzaqFarijul Bari TalukderNo ratings yet

- List of Names of Allah With The Evidences - by Ash-Shaykh Yahyaa Bin 'Alee Al-HajooreeDocument17 pagesList of Names of Allah With The Evidences - by Ash-Shaykh Yahyaa Bin 'Alee Al-Hajooreehttp://AbdurRahman.org100% (2)

- A Selection of Wise Sayings of Ibn Taymiyyah.Document2 pagesA Selection of Wise Sayings of Ibn Taymiyyah.zaki77100% (3)

- Islam and The Destiny of ManDocument250 pagesIslam and The Destiny of ManFaten Mohsen-Clark100% (1)

- Military StrategistDocument7 pagesMilitary Strategisthunaiza khanNo ratings yet

- The Muslim December 2007Document4 pagesThe Muslim December 2007ramadNo ratings yet

- List of Cbcs Kutawato Cluster Network Member-Org. 1. Kutawato Region Name of Organization Head of Office Office Address Email Address Contact Numbers Status RemarksDocument4 pagesList of Cbcs Kutawato Cluster Network Member-Org. 1. Kutawato Region Name of Organization Head of Office Office Address Email Address Contact Numbers Status RemarksRuben UmalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Fiqh (Era of Khulafa' Ar-Rasyidin)Document19 pagesIntroduction To Fiqh (Era of Khulafa' Ar-Rasyidin)Ummu Mukhlis100% (1)

- Ploting Pengawas To Uin Gusdur PekalonganDocument43 pagesPloting Pengawas To Uin Gusdur PekalonganImam GozaliNo ratings yet

- Tugas Dan Pemberian Identitas TanamanDocument1 pageTugas Dan Pemberian Identitas TanamanIka NurhayatiNo ratings yet

- Word GodDocument5 pagesWord GodAsad HoseinyNo ratings yet

- Milad ProofDocument9 pagesMilad Proofmrpahary100% (1)

- The Maqtal of Imam Al Hussain Narrated by Imam Al-SajjadDocument17 pagesThe Maqtal of Imam Al Hussain Narrated by Imam Al-SajjadThe Purified Truth الحق المبين86% (7)