Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Michel Serres - Science, Fiction, and The Shape of Relation

Uploaded by

rammellzeeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Michel Serres - Science, Fiction, and The Shape of Relation

Uploaded by

rammellzeeCopyright:

Available Formats

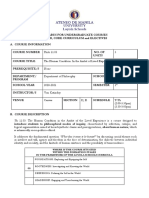

SF-TH Inc

Michel Serres: Science, Fiction, and the Shape of Relation Author(s): Laura Salisbury Reviewed work(s): Source: Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1, Technoculture and Science Fiction (Mar., 2006), pp. 30-52 Published by: SF-TH Inc Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241407 . Accessed: 21/02/2012 21:09

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

SF-TH Inc is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Science Fiction Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

30

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME (2006) 33

Laura Salisbury Michel Serres:Science,Fiction, and the Shape of Relation

In Eclaircissements: cinq entretiens avec Bruno Latour (1994, translatedas Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time), Bruno Latour suggestively reaches out to a figure from science fiction in his attempt to describe the strangelyundisciplined, interdisciplinary work of Michel Serres. Latourasks Serres, who has writtenon subjectsas diverse as information theory, the physics of the Roman poet and philosopherLucretius, fluid dynamics, contemporary ecological imperatives,and Emile Zola, "why in the space of one paragraph,do we find ourselves with the Romans then with Jules Verne then with IndoEuropeans,then, suddenly, launchedwith the Challengerrocket, before ending up on the bank of the Garonneriver?"(Serres and Latour43). Latourproposes that Serres proceeds throughthe use of a something like a conceptual "time machine"(79). After all, he seems resolutely indifferentto temporaldistances, being able to suggest that Lucretius may be more our contemporaryin his presentationof the world as a chaotic and turbulentswirl of atomsthanNewton is in imaginingthe world as a percussive and concussive collection of billiard balls.1 It is easy to see what Latourmeans here, for Serres's poetically resonant folding together of subjects, spaces, and times creates a map of new and unexploredshortcutsand pathways, wormholesthatjoin togetherpositions and momentsthatphilosophy,history, science, and literature have traditionally held quite distinct. Serres, however, rejects Latour'smetaphorof the time machine, which he fears is infected with the idea of travelingbackwardsalong the line of time. "[T]he words machine and backwardin time bother me," states Serres, for "set in motion on its railroadtrack, such a locomotive is the embodimentof linear time" (79). Serres's resistanceto Latour'sproposition revealsa ratherlimitedconception of the metaphoricalpossibilities offered by time travel, for he only sees within it suggestionsof a conventionaland even potentiallytyrannicalversion of linear time. Perhapsthe time machineremindsSerres of H.G. Wells's 1895 novella, in which time travel projects the future of the world as an inverted Hegelian dialecticof historicalprogressionthatleadsnot to pure Spiritbutto degeneration and the heat deathof the Earth. Serres wants no part of such a vision of linear, historical temporality,which he reads as taintedwith conflict and the violence of dialectical supersession. Serres presents himself instead as an irenic philosopher(a thinkerof peace ratherthan war) who is able to bring together temporallydistantelements and epochs throughan understanding time not as of a line in which the past is necessarily excluded andovercome, but as a turbulent and chaotic system of "stopping points, ruptures, deep wells, chimneys of thunderousacceleration,rendings, gaps" (Serres and Latour57). The time that interests Serres percolates-sometimes working through, sometimes working back-rather than passes (58).2 So Latour withdraws his metaphor. It is not

SERRES: AND THESHAPE RELATION SCIENCE, FICTION, OF

31

Serreswho travelsthroughtime, along its line; rather,the philosopheris simply attentiveto the way in which thingsbecome unexpectedlyclose or distantwithin a temporalitythatis chaotic and turbulent,a time that is more meteorologicalin its movementsthan classically historicist. It is perhapsno surprise,then, thatthe one authorSerreswho has writtenon that has a place within the canon of science fiction is Jules Verne ratherthan Wells (see Jouvences and "JulesVerne"). For Verne's version of time travel in Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) fmds a past that has not yet been overcome, a past hiddenwithin the center of the Earththat is accessible only by passing throughthe infinitecomplicationsof turbulent flows and a space that ice folds time-a volcanic shaft that links surface and center, presentand past. But Serreswrites thatin the works of Verne, "thereis only a technologyof vehicles and communication," only balloons, aerostats, submarines, steam engines, airplanes,railways, and "notone word of what commonly goes by the name of science fiction" ("Jules Verne" 175). Revealing again a rather limited conceptionof sf, he presumablymeansthatthereareno impossibletechnologies, no time machines. And Serres certainly works more to find suggestive symmetriesamong Verne, Greek myth, andAlice's Adventuresin Wonderland (1865), thanany connectionwith otherscientific romancesof the period. In fact, he displays a resistanceto such "genre fiction," revealing throughout work his a powerful preference for canonical authors: Zola, Moliere, Balzac, La Fontaine, Rousseau, and Musil, among others. Serres's relevance to sf studies clearly does not lie in his specific readings of texts, then. However, his insistence on mappingthe passages between discourses and genres that would conventionally appear to be spatially and temporally distinct, alongside his creationof a methodthatrevealsthe productivehybridityof disciplines, suggests that there could neverthelessbe linkages and relationshipsbetween his theories and science fiction that Serres himself has not explored. Hermes: Science and Literature. Despite a seemingsuspicionof science fiction as a category, Serres's work of the 1960s and 1970s persistentlydemonstrates an explicit interestin the passage between science and fiction. He complainsto Latourthatwhen he startedwriting, "thebifurcatedrelationship betweenscience and literaturewas so frozen, so distant,thattwo eternitiesseemed to be looking at each other like two porcelaindogs-like two stone lions flankinga doorway" (Serres and Latour47). His work explicitly opposes such ossified disciplinary purity, seeking out what he finds to be always already there in diverse philosophical, scientific and literary texts-a complex, twisted, and enfolded passage between the science and the humanities.One of Serres's maxims is that "[t]hereis no pure myth except the idea of a science that is pure of all myth" (Serres and Latour 162), and his monumental five-volume series Herme's, publishedbetween 1968 and 1980, works to demonstrate thatscience shouldnot be regardedas offering an objective or unmediatedview of the world; rather, it is a cultural formationthat has its history and complex place amongstother discourses.3 In a mode thatis now recognizableto us via Foucauldian historicism and the cultural history that has become so influential in the humanitiesand

32

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME (2006) 33

social sciences during the 1980s and 1990s, Serres insists, contrary to the institutionaldisciplinary separationsand the increasing specializationsof the period, on the developmentof scientific, literary,andphilosophicalworld-views that are imbricatedwith one anotherin complex and suggestive ways. Hermes IV: La distribution(1977), for example, explores the nineteenthcentury rejection of Cartesianmachines in favor of models of motors and the laws of thermodynamics. "As soon as one can build ... steam or combustion engines, chemical, electrical, andturbineengines, and so forth," writes Serres, "the notion of time changes. The second law of thermodynamicsaccounts for the impossibility of perpetual motion.... [E]nergy dissipates and entropy increases" (Hermes71). But the notion of the "heatdeath"of the universe and the inevitablecessationof all work, all change, which is foundin scientific tracts from the 1840s onwards, is not restrictedto a single discipline; instead, works from Marx to Freud, Zola to Turner, Nietzsche to Bergson, are connectedby the same models and metaphors,both reflecting and in some cases anticipating the production of seemingly "objective" scientific knowledges through a complex series of significantlynon-linearrelationships.In Hermes IV, Serres writes that he discovered duringhis writing of Feux et signaux de brume:Zola (1975) that the history of science "offers less interest as an object or domain than as a set of operators, a method or strategy of working on formations differentfrom itself" (Hermes39). He readsZola's texts as structured according to the scientific models of genetics with which the authorwas familiar. More significantly, though, Serres suggests that the horrors of heredity, the playing out of genetic flaws that structureand scar Zola's Rougon-Macquart novels, actually anticipatethe discovery of thermodynamicmodels of the world. As Harariand Bell point out in theirexcellent introduction the Englishtranslation to of Hermes, the imperatives of sex and death, heat and cold, that circulate throughthe structuralgenetics of these novels create a "genetictreatise that is itself the materialization a cosmology of heat-a steam engine" (Harariand of Bell xviii). Serres can thus write thatthe "steamengine [that]circulatestherein among the hereditaryflaws and murders"of Zola's novels and the "thermodynamic grill" that stretchesacross these texts, reveal much more of the cultural formationof the nineteenthcentury than a neat and hermeticallysealed history of the novel or an equally distinct history of science (Hermes 39-40). As soon as attentionis paid to the unexploredpassage between the apparentlydiscrete discourses of science and fiction, it becomes clear that the space of the relationshipis more complex than simply connective. Because Zola's texts are necessarily born in a space of communicationbetween multipledomains, there are other, seemingly more logically distant "sets of operators"that inform the texts. Serres ratherunexpectedlyreads Zola's explorationsof literarynaturalism, his scientific exploration of genetics and anticipationof thermodynamics,as bisected by the structuresand imperatives of myth. In Zola, he asserts that mythic discourse is "une entreprise de tissage" [a process of weaving], whereby, as AndrewGibsonputsit, "connectionsare establishedbetweenplaces and spaces that are remote or isolated or inaccessible from, closed to, danger-

SERRES: SCIENCE, AND THESHAPE RELATION FICTION, OF

33

ous, even deadly to each other" (90). Strangely, then, Zola's Paris can be read as having a mythic geography, because it is populatedby characterscirculating, accordingto the engines of their genetic instincts, throughand between spaces that initially seem as heterogeneousand distinct from one anotheras the island spaces of Homer's Odyssey. In Hermes IV, Serres describes how these isolated spaces in Zola's texts are woven together, connected and disconnected, by bridges, wells, labyrinths- "spatialoperators" -that aretopologicallyanalogous to the topographicalshapes of Greek myth (Hermes 42-43). Topology, which holds a fascination for Serres throughouthis work, is concerned with "the propertiesof figures and surfaces which are independent of size and shape .. .; hence, with those abstractspaces that are invariantunder homeomorphic translation" ("Topology" 2081). As Steven Connor puts it, topology is a mathematics of surfaces that involves "actions of stretching, squeezing, or folding, but not tearingor breaking"shapes ("Topologies" 106). Topologically speaking, then, a teacup and a doughnut are isomorphically identical: teacup and doughnutcan be stretched, squashed,or shaped into one another without piercing the surface of the form. One significant aspect of topology for Serres is the fact that points that seem metricallydistantfrom one another(say, the bottom of the teacup to the outer rim of the handle), can be shown to be adjacentto one anotherunder isomorphictranslation.Where both Euclideanandnon-Euclidean metricalgeometryis concernedwith measurement and with "the science of stable and well-defined distances," topology is "the science of nearness and rifts" (Serres and Latour 60), of continuity and contiguity. For topology is concerned with demonstratinghow the spatial relationsof measurementare subjectto unpredictable shifts, as what appearsat one moment to be the inside of the form can be warped into its outside under topological analysis. For Serres, Zola's texts are traversedby spaces that, once understood topologically, reveal unexpected passages, links, or similarities between realms that would usually remain socially distinct. Alongside the thermodynamicmotor of drive and decay, the figures and structuresthat are folded into Zola's scientific discourse and his literary naturalism can be understood as working in isomorphically identical ways to the chimerical spatialityof Greek myth. Borrowingequally from structuralism historicism,4SerresreadsZola so and that "thetext turnsinside out like a glove and shows its function"(Hermes47). The "spatial operators" at work in the texts produce an unexpected mythic geography within the scientific discourse of naturalismand the tragedies of social transgressionthat attend it, unfolding ways of reading that reconfigure character, language, and theme into new relationshipswith one another. So Serres can argue that within both myth and this nineteenth-century literary discourse, "connectionand non-connectionare at stake, space is at stake, an itinerary is at stake. And thus the essential thing is no longer this particular figure, this particularsymbol, or this particularartifact;the formal invariantis something like a transport, a wandering, a journey across separated spatial varieties" (43). For Serres, this "transport"is "the elementary program of topology" (44). At this historicalmoment, as conventionalaccountshave it, the

34

SCIENCE 33 FICTION VOLUME (2006) STUDIES,

modem discoursesof naturalismandrationalitytriumphover mythicalaccounts of the world: "Euclidean space ... repress[es] a barbarous topology" and "transport displacementwithoutobstacles" takes the place of "the ancient and journey from islandsto catastrophes,from passageto fault, frombridge to well, from relay to labyrinth" (52; emphasis in original). Spaces are separable, ordered,disciplined.But Serresdescribeshow mathematics returnsto its origins within this same historical moment. Just as mythicjourneys appearwithin the discourse of literary naturalism,topology emerges as a science in the work of Johann Listing and James Clerk Maxwell. So at the very moment when we appear to have "an aged Europe asleep beneath the mantle of reason and measure, mythology reappears as an authentic discourse" (53) within the nineteenthcentury. Of course, for an Anglophone readership,this warping of the topography between inside andoutside, this creationof unexpectedpassagesbetween realms that ought, conventionally, to remain discrete, is more reminiscentof a rather different genre of writing from the latter half of the nineteenth century. Although Serres makes no mention of it, thefin-de-siecle Gothic, which holds a centralplace within the conditionsof emergenceof science fiction, sharesand representsin even more sensationalterms Zola's fascinationwith the depravity and degenerationperceived to be at work within the labyrinthinemoderncity. Like Zola's "steamengine" of literarynaturalism,the evolutionaryparadigm, degenerationanxiety, and discourse of scientific naturalismthat all subtenda text like RobertLouis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), reveal it to be one of manynineteenthcentury"fictionsof science, even if it is not useful to call them science fiction" (Luckhurst23). And following Serres's readingof Zola, the illegitimateenfolding of diverse temporalitiesand spatialities within the Gothic, in which the threateninglyarchaic returns to menace the present and the borders and boundaries of both psychical and geographical space are subjected to unpredictable metamorphoses, might similarlybe understoodin topological terms. The descriptionof the house in which Jekyll and Hyde reside seems to resist the stablemeasurements conventionalgeometrymight wish to impose on it. that Entered from the front, the house appears to be one of "great wealth and comfort"; it is warm, homely, "afterthe fashion of a countryhouse" and thus far from the cold alienationof urbanspace (18). Jekyll's residence is set within the geometrical, gridded certainty of Cartesianspace-"a square of ancient, handsomehouses" (17)-and remainsreassuringlyintactand coherent, despite the fact that most of its neighboringdwellings have been separatedand "let in flats and chambers to all sorts and conditions of men" (17-18). But the laboratory throughwhich Hyde makeshis entrancesandexits is, by contrast,the most unheimlichof spaces. Approached througha dim bystreet, this windowless and "sinisterblock of a building," which bears "the marks of prolonged and sordidnegligence" (8), "seems scarcely a house" (11) at all. It is indeeda space that will not yield itself to measurement, "for the buildings are so packed together about that court ... it's hard to say where one ends and the other begins" (11). In the mythical space of the city as labyrinth, the house and

SERRES: AND THESHAPE RELATION OF SCIENCE, FICTION,

35

laboratoryare connectedthrougha rift or fault line in rationalspace, just as the of architecture the psyche, in which conscious and unconsciousare supposedto remainrelativelydistinct, is warpedinto the Gothicmonstrosityof Jekyll/Hyde. Topology also makes sense of the instabilityof outside andinside thathauntsthe scene. Jekyll, who is all outwardrespectabilityand the exteriorityof socially sanctionedbehavior, resides within descriptionsof cozy interiority-of hearths, furnitureanddomestic servants-while Hyde, who is nothingbut the interiority of libidinal forces, is only ever explicitly connected to the descriptionof the laboratoryas an unreadableblank of exterior surface that has no windows and a door that admits only him. In topological terms, Jekyll and Hyde could be thought of as a toroid (a doughnut shape). In place of the relative lack of complexity of a sphere or cube in which all visible surfaces are reassuringly exterior, the hole that rends the book into a textual toroid produces a shape in which inside and outside are disturbinglycontinuous. Science fiction's use of Gothic tropes is well-documented, as future is anxiously enfolded into the concerns of the present, or the integrityand proper limits of the humanbody are subjectedto more or less violent reconfigurations. Indeed, the codification of temporal and spatial instability within this genre allows the cyberpunkfictions of the late 1980s and 1990s to be read as part of what might be thought of as a second wave of fin-de-siecle Gothic. Dani Cavallaro notes a connection between the tropes of cyberpunk and Gothic architecture, in which the past is recuperatedand the meaning of its style reconfiguredby its eruptioninto the present(176). Borrowingmore of its visual language from cyberpunkthan from Philip K. Dick's Do AndroidsDream of Electric Sheep? (1968), Ridley Scott's 1982 film Blade Runner certainly explores a Gothic Los Angeles, full of crumbling edifices of the past, halfabandonedand hollowed-out buildings-the dark, uncanny interior spaces of memory and mourning. Cavallaroargues, however, that within cyberpunkthe Gothic also becomes the favored style for describingthe resultsof the interface between humans and technology. William Gibson's famous and founding definitionof cyberspaceas "[u]nthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non-space of the mind, clusters and constellationsof data, like city lights receding" (Neuromancer67), rendersit a "foundationless space" of "limitless surfaces"(Cavallaro175)-a space closely associatedwith Gothicaffect andthe terror of the ungraspablesublime. Drawing upon distinctions elaboratedby Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Cavallaro argues that Gothic space is a "smooth space ... denot[ing] fluidity, boundlessness and the collapse of rationalizinggrids" that can be contrastedwith "striatedspace, the symbol of order,classificationandcategorization" (177; emphasisin original). Cyberpunk, by this analysis, incorporatesGothic disorder into the spatial rationalism of traditionalsf. Cavallarodoes not note, however, thatGibsonworkswith two geometrically and politically opposed representationsof cyberspace in his texts. As Nick Binghampoints out, the version of cyberspacethat appearsat the beginningof the 1995 film of JohnnyMnemonic(for which Gibson wrote the screenplay)is "a gridded, Euclidean world, stretching uniformnlyand endlessly in all

36

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME (2006) 33

directions: a geo-metric totality" (248). In "Burning Chrome" (1982), the corporatecyberspacevisible to "legitimateoperators"is similarly represented as a "3-D chessboard, infinite and perfectly transparent"(195). Later, it is envisaged as "brightgeometries representingthe corporatedata.... Towers and fields of it in the colorless nonspaceof the simulationmatrix"(197). Here, the sublime is invoked through scale and the power of function. But despite corporations'wish to control the infinite networkof data by modulatingit into rational, totalizable forms and localities, the cowboy heroes of Gibson's texts are able to hack into these predetermined networks and pathways. The cyberpunk achieves a technologized version of the Situationist derive by rerouting corporate space and exploiting the topological peculiarities of the complex but continuoussurface of the network. The cyberspaceto be found in the second half of JohnnyMnemonic, which is entered using stolen hardware and hacking skills, is thus very different from the previous version of gridded totality. It takes on the appearanceof an infinitely malleable surfacethatcan be unfoldedandmoldedat will, as Johnny'shands, wired into a VR interface,work to uncover and unfold the pockets of data and informationthat exist in its unlocalizablespace. The network of cyberspace thus belies its corporate representationas totalizable,stablewithinthe realmof Euclideangeometry. For cyberspaceis not the agglomerationof discrete partsthatcould submitto being mappedfrom the outside or from above. Even Johnny's body, seemingly fixed in the Euclidean space of the "real" (connected to hardwareand moving little more than a few feet over a suggestively griddedboard), is actuallyenfoldedwithin an infinitely complex informationinterfacethatenables Beijing and Newark momentarilyto touch one another.Just as Gibson's conceptionof the technologicallyenhanced body in "BurningChrome" similarly blurs the boundariesbetween flesh and machine ("leads [are] clipped to the hard carbon studs that stick out of my stump"[201]) by turningembodimentinto a networkof technicalrelations, the matrix itself assumes a symbiotic and dispersedcorporealityto be imaginedas an "extendedelectronic nervous system" (197). As Jack implies, cyberspace, with its links to the embodieduser, is a networkthat always has the possibility of reshapingitself or undergoinghomeomorphictranslation:the "matrixfolds itself aroundme like an origamitrick"(216), statesJack, as he finally bends and scores Chrome'scorporatespace beyondrecognition.Following one of Serres's favorite theses that myth informs, enriches, and even subtendsthe discourse of science, the cyberspace of the console cowboy can thus be read as another mythic space-a space of journeys, displacements,translations,andtransformations-that cannotbe reducedto the totalizableor striatedshapes of Euclidean geometry.' It would also be importantto note that the scientific modeling of communications networks, andof cyberspacein particular,has takenits figures and tropes-sublime "[u]nthinkable complexity"and the topologicalpeculiarity of a space that is both global and local-from the discourse of both Gibson's science fiction and, more fundamentally,the languageof myth.6 Topology states that some geometric problems are not dependent on the precise shapeof the objects involved; what is significantis how these shapesare

SERRES: AND THESHAPE RELATION SCIENCE, OF FICTION,

37

mathematical connected together. The fundamental purposebehind topology is that by concentratingon the configurationof passages and connections rather than static points in space, it is possible to see structuralsimilaritiesbetween problemsthat seem, at first glance, to have little relationshipwith one another. Once the invariantqualities of the problemhave been identified, it is possible to work with a geometric problem that may have proved unsolvable in one particular form, within the potentially more welcoming environmentof the other. Serres's work is, of course, similarlyobsessed with such homeomorphic translations between seemingly radically distinct discursive environments. Readingtopologicalcomplexitydoes not simply enable Serresto drawnew maps of the stable terrainof literature,philosophy, myth, and science; instead,just as the teacup needs to be worked in order for its points to resemble the doughnut in metrical space, so Serres's philosophy stretches and explores the spaces of and passages between epistemologies that are usually kept distinct from one another. In the first phase of Serres's work, it is thereforeno surprisethatthe tutelary house-god of this projectis the cunningand ingenious Hermes, the protectorof boundarieswhose statueis placed at crossroads. Hermes-god of commerceand theft and founder of alchemy (hermeticism), among other sciences-is the demiurge of plural spaces, guiding travelers along and between uncertain topographies and standing, as Latour has it, for "mediation, translations, multiplicity"(Serres and Latour 1). The final volume of the Hermes sequence published in 1980 is thus subtitledLe Passage du nord-ouest (The Northwest Passage) because it tells of the difficult journey between disciplines whose itineraryis not predicted from the outset and whose map is the process of the passage. The space between disciplines through which Hermes passes is the realm of ice flows, jagged shores, and the randomly scattered islands. This journeythroughthe northwestpassage is thusa randonnee,what HarariandBell describe as "an expedition filled with random discoveries that exploits the varieties of spaces and times" (xxxvi). For the space in between disciplines is seen by Serres as still very much underexploredand far more complicatedthan the idea of an "interface"between two stable concepts would suggest. "It's more fractalthantruly simple," Serres tells Latour;it is "less a junctureunder controlthanan adventureto be had. This is an area strangelyvoid of explorers" (Serres and Latour70). Bruno Latour asserts that Serres's topologically complex philosophy is amodern:it does not accept the distinctionbetween the ordersof fundamentally things that divide the naturalfrom the culturalor social, and that is the legacy of what it means to consider oneself modern. In such "modern"terms, it seems nothing other than madness for Serres to assert in Statues (1989) that the explosion of the space shuttleChallengerin 1986 and the incinerationof human sacrifices within a brass statuededicatedto Baal in Carthagestrangelyresemble one another. It seems like science read as a most peculiarkind of mythological fiction.7 For, as Latourputs is, we moderns can only see the Challengeras a technicalobject, while religious sacrifice is a social phenomenon:"tobe modern is precisely to accept that Challengerhas nothingto do with Baal, because the

38

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME (2006) 33

Carthaginians were religiousandwe no longerare.... [T]herevolutionsthathave made us modem have in fact made these past states incommensurable" (Serres and Latour 138-39). In topological terms, though, they may be linked by structuralresemblances and connectivities. To see the relationshipbetween Challenger (the technological object of modem science) and Carthaginian sacrifice (the social object of a mythologicaland religious world-view) is to see how our scientific tools, technologies, and objects are implicated within those atavistic, libidinal, irrational,and transcendental impulsesthathave persistently appearedwithin culturalformationsas the Gothicundersideof a positivismthat drawsits strengthfrom the Enlightenment project. Of course, science fictionhas always worked precisely to explore the culturaleffects and affects of projected scientific advancement.Sf has continually read the rational space of modem science as implicated within the disruptive, irrational(in terms of Euclidean geometry), and often uncanny spatialitiesthat are figured by the humanhopes andfearsthatattenditsjourneys, translations,andtransformations. Serre'swork offers science fiction studiesa theoreticallanguagefor mappingthe contoursand bifurcationsof the passage between science and fiction; it also offers a language for creating and exploring the topologically complex cognitive and imaginative spaces within which such connectionsmight be projected. Noise and Sense. There is perhapsa familiar flavor to some of the ideas that Serres presentshere. The fetishes that injectedsuch frissons into the discourses of postmoderntheorizationsof culture in the 1980s and 1990s all seem to be there: multiplicity, liminal spaces, hybrid knowledges, chaos, the pluralityof meaning, incommensurability,and the revelationof the discursive qualitiesof seemingly objective disciplines such as history and science. Serres workedwith Foucault in the 1960s, and Hermes I includes specific engagementswith his work; Serres is referencedin TheArchaeologyof Knowledge(1969), Deleuze's TheFold (1988), Deleuze and Guattari'sCapitalismand Schizophrenia (1972), and Derrida's Given Time: Counterfeit Money (1991, see Berressem 52). It is clear, then, thathe can hardlybe thoughtof as being excluded from the climate of "French Theory" that dominated the Anglo-American academy and the of metalanguage postmodemliterarystudiesin the 80s and 1990s. Nevertheless, while sympatheticto the work of Foucaultand Deleuze (see Serres and Latour 38-39), Serres's work, particularlyfrom the 1980s, demonstratesan implicit critique of those theorists of postmodernitywhose interest lies primarily in reading the exchange of signs. It is thus perhaps this theoretical interest in "narratives,"and its sometime refusal to grantthe particularity quiddityof and things behind the circulation of signs, to which Serres's work can be most productively opposed. Indeed, Jean Baudrillard's lamenting acceptance of a technologizedworld of rapidlyexchangingsigns and simulacramight be taken as representative of what Serres finds to be the materially impoverished philosophiesof languagedominantwithinthe period. He worries that "language replaces experience. The sign, so soft, substitutesitself for the thing, which is hard. I cannot think this substitutionas an equivalence.... My book, Les cinq sens, cries out against the empire of signs" (Serres and Latour 132). In the

SERRES: SCIENCE, FICTION, AND THE SHAPE OF RELATION

39

work that follows the final volume of Hermes -Le parasite (1980; The Parasite), Gene'se (1981; Genesis), and Les cinq sens (1985; The Five Senses)-Serres neithercelebratesnor simply opposes the circulationof signs; instead, he pares back the philosophicalobsession with languageand discursive structuresof the 1970s and 1980s to its most basic elements. That interest in languageis reconfiguredas an engagementwith the very channelsof communication itself-those prepositionsthat precede statementsor postulates and that are the fundamentalground of language. For Serres, before language, before even the word, therewas noise, a "background noise, which precedes all signals and is an obstacle to their perception" (Serres and Latour 78). This noise, against which previous philosophies have blocked their ears, is both the very possibility of language and its interference; it is the multiple sound of the universe that "the intense sound of languagepreventsus from hearing" (78). Hermes was always interested in the transmission and unpredictable transformationof messages through topologically diverse spaces, but Serres extends the interest in informationtheory displayed in Hermes IV in the work that follows it. Information theoryuses mathematicsandprobabilityto describe the relationshipbetween intendedinformationand white noise in the channels of communication between a sender and receiver. As Serres puts it: "[i]nformationtheory follows directly from thermodynamics. It studies the transmissionof messages, the speed of theirpropagation,theirprobability,their redundancy"(Hermes IV; qtd in Harariand Bell xxiv). Serres is not the only writer to suggest thatthe deep metaphorthat structuresthoughtin the twentieth century-from the unconscious to the computerto the genome-is that of the code; but Serres asserts that all creationsof systematicorder, all the biological transformations life, every scientific system, are formsof coding thattransmit of informationdown diverse channels:

What is mathematicsif not languagethat assures a perfect communicationfree of noise? What is experimentationin general if not an informationalas well as an energeticevaluationof the laboratory? Whatis a living system if not an island of negentropy, an open and temporaryvortex that emits and receives flows of energy and information?What is a language, a text, history itself with its traces and marks, if not objects of which the theory of information defines the functioning?(HermesIV; qtd in Harariand Bell xxiv)

In order for these diverse systems of coding to speak to one another, the philosopher's work must establish pathways of communicationbetween this networkof systems; it must also read communicationitself as an enactmentof the turbulent between contingentpockets or figures of orderandthe relationship swirling disorderthat is its ground. In the later Genesis, Serres will write that "[n]oise is the basic element of the softwareof all our logic, or it is to the logos what matter used to be to form" (7). Communicationonly emerges from background noise, from signs differentiatedfrom an infinitecacophonyof other signs and from the static that will not admit to being read as a sign at all. In Herme'sII: L'Inteiference (1967), Serres also describes how communication between people, dialogue, is best thought of as "a game played by two interlocutorsconsidered as united against the phenomenaof interference and

40

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 33 (2006)

are confusion"(Hermes He suggeststhatthese interlocutors not dialectically 66). opposed; rather, "they are on the same side, tied togetherby mutualinterest: they battle againstnoise" (67). In fact:

To hold a dialogue is to presume a third man and to seek to exclude him; a successful communicationis the exclusion of the thirdman. The most profound dialecticalproblem is not the problemof the Other, who is only a variety-or a variation-of the Same, it is the problem of the third man. We might call this third man the demon, the prosopopeiaof noise. (67; emphasis in original)

By 1980, this prosopopeia has anotherface: the excluded third, the demon, is called the parasite. Serres chooses the figure of the parasite because the word bears a useful triple meaning in French: it is a biological organismthat invades and lives off another; a sponger or guest who outstays his or her welcome, giving only conversationratherthanmaterialremuneration; the term for noise or static and in information theory. In biological, social, and communicative terms, the parasite is a "thermalexciter" (Parasite190) that causes fever and inflammation, interruptingand incapacitatingthe functioning of a system through its noise. The parasite excites the system to the degree that a message sometimes cannot pass at all; nevertheless, it is also, significantly, the possibility of any communication."[W]hitenoise is the conditionfor passing(for meaning,sound, and even noise), and the noise is its prohibitoror interception.... Heat a little, I hear, I send, I pass; heat a little more, everything collapses" (194), writes Serres. The parasite, like the excluded third man in dialogue, is integralto the system from the start: its noise precedes and perturbsthe system; but noise is also part of the production of the system-indeed, it forces the system to increase in its complexity. Given thathe sees the actionof the parasitewithin all informationsystems, Serres's projectis thus to demonstratephilosophically,as chaos theory, informationtheory, and fluid dynamics have done within their disciplines, thatorderedsystems are significantexceptions ratherthanthe rule. As Harariand Bell put it, for Serres, "it is necessary to rethinkthe world not in terms of its laws and regularities, but rather in terms of perturbations and turbulences, in order to bring out its multiple forms, uneven structures, and fluctuatingorganizations"(xxvii). Genesis,which Serres later said should have been called Noise ("an old Frenchword thatexpresses clamorandfuror"[SerresandLatour74]), explores furtherthis static-the sound, the ur-conditionof the materialuniverse-and its complex relationshipwith systems of contingentorder. Still under the divine protection of Hermes, the philosophy of communications (in the broadest possible sense) that appears in Genesisis able to "conceive the message as order, meaning, or unit" but can also conceive "the backgroundnoise from which it emerges" (110). The figure of turbulencethat resounds and repeats within the poetic and incantatoryframework of Genesisis Serres's way of paying attentionto the multiplicity of the sensible world that philosophy and science reject in their quest for "a principle, as system, an integration ... of elements, atoms, numbers"(2). Again, he repeatsthat the multiple, appearing

SERRES: AND THESHAPE RELATION SCIENCE, OF FICTION,

41

as a complex interactionbetween undifferentiated noise andnegentropicislands of transient order, is not to be thought of as out of the ordinary or as "an epistemologicalmonster";instead, it is "theordinarylot of situations"(5). For Serres, "turbulence a multiplicityof local unities and of pure multiplicities," is or, with greater complexity, "a chaotic multiplicity of orderly and unitary multiplicitiesand chaotic multiplicities"(110). And these turbulentsystems, in which there are both ferment and quasi-staticeddies, are to be found in many places. Turbulenceis in the weather, in river flows, in a linguistic message, in twisting columnsof smoke, in the pulsingof blood throughthe body, even in the order/disorder of individual corporeality itself, which is a "temporary turbulence," a contingent and circumstantial linking together of smaller turbulences (110). Turbulenceis thus widespread, but, crucially, it exists in multiple distributionsratherthan as a universal state. The analysisof the flows andthrusts,the prepositionsthatlink togetherthese turbulentsystems, become, perhaps unexpectedly, part of Serres's project to construct "a decent philosophy of the object" (Genesis 91). Because the conventionalobject of modem thought "lies precisely outside of the relational circuits that determine society," writes Serres, he attempts "to think a new object, multiple in space and mobile in time, unstable and fluctuatinglike a flame, relational"(91). By producing"reflectionson the multiple"(91), Serres grants objects their rightful position within the construction of the world. Seemingly rejecting the phenomenologicaldesire to see the thing in itself as it really is, Serresconcentratesinsteadon the significanceof what he calls "quasiobjects." In Genesis, Serres uses the example of a ball to explain the figure of the quasi-objectthat appearsin The Parasite and Rome: le livre des fondations (1983; Rome: TheBook of Foundations).Althoughthe ball has certainparticular physical qualities, its significance lies in the fact that it is fundamentallya "relationalobject" (Genesis 87) ratherthan an object with its own distinct and separablebeing: "Aroundthe ball, the team fluctuatesquick as a flame, around it, through it, it keeps a nucleus of organization. The ball is the sun of the system and the force passing among its elements, it is a center that is offcentered, off-side, outstripped"(87-88). The kernel of the object itself has a limited significance, except that it forms a center of attraction;instead, it is within the relational network constellating around the ball that meaning is located. The ball is a quasi-objectratherthanan essential object, because when viewed as part of a network of communicationsand exchanges of information, it reveals itself to be "moreof a contractthana thing" (88). The ball as a quasiobject thus not only reveals its own presence and interventions,it demonstrates that human subjectivities and collectives must also be viewed as part of a multiple interfacewith the non-humanobject world. As Serres goes on to write

inLe'gende anges(1993;Angels: Modem des A Myth),"[l]iving thingsandinert

things bounce off each other unceasingly;there would be no world without this interlinkingweb of relations, a billion times interwoven" (47). Serres asserts the social importanceof the quasi-objectby explaining, in Genesis, that the crucial difference between humanand animal societies is the emergence of objects. "Ourrelationships,social bonds, would be airy as clouds

42

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME (2006) 33

were there only contractsbetween subjects"(87), he muses. As "the luminous tracer of the social bond" (87), objects slow down the relationshipsbetween subjectsand what would otherwise be their quickenedand simplified reactions to the world. Human societies are fundamentallystructured and stabilized according to exchanges within a network of objects that are invested with a culturalvalency thattranscendsany simple use value. Any object investedwith desire or fear traces a silent contractwith the human. A good, simple example of what Serres means by the quasi-object might be the vestige of human civilization representedby the conch shell in Lord of the Flies. The object itself is valueless; as a quasi-object,though, it "stabilizes ... relations"(87), it slows down instinctive interactionsto create a contractthat is "heavierand denser" (SerresandLatour201), addingcomplexityto the systemof humanrelationsand even fundamentally workingto constructa society thatvalues the voice of each individual.As Serresgoes on, ratherradically,to put it in Angels, it is a mistake to imagine that the ball in a game is simply being manipulated by human subjects; rather, Serres's peculiar empiricism leads him to assert that the ball itself "is creating the relationshipbetween them [human subjects]. It is in following its trajectorythat their team is created"(Angels 47-48). If the ball is a quasi-object,a "trackerof the relations in the fluctuatingcollectivity around it" thatactuallymakes it the "truesubject"of the game, the skilledplayer is also perhapsonly a quasi-subject,in that he "knows that the ball plays with him or plays off him, in such a way that he gravitates aroundit and fluidly takes the position it takes, but especially the relationsit spawns"(Serresand Latour108). This newly reconfiguredsubject is no longer an individual, a modem subject; instead, s/he is held together by multiple cords, contracts, and channels of communication.S/he is a constellationof relations and becomings ratherthan a being. As Serres puts it in The Parasite, the quasi-object that constructs, positions, and shines a light upon the subjectreveals that it is never simply and essentially itself (as nothingfor Serres ever is):

The quasi-objectthat is a markerof a subject is an astonishing constructorof intersubjectivity.We know, throughit, how and when we are subjectsand when we are no longer subjects. "We": what does we mean? We are precisely the fluctuating back and forth of the "I." The "I" in the game is the token exchanged.And this passing, this networkof passages, these vicariancesof subjects weave the collection. (227)

During the 1980s, Serres's peculiar empiricismattemptsto free itself from the discourse of rational science and from what he, not always convincingly, finds to be the crushingly second order investigationsof phenomenologyand linguistic critique. Although Serres states that science seeks to assert its objectivity,its freedomfromthe complex cordsof the quasi-object(Genesis90), in Les cinq sens he demonstrates thatsensory embodimentrendersit impossible to stand in front of or outside the world, to free oneself from its entangled networksandthe multiplespaces andtimes tracedby the circulationof objects.' As far back as Hermes IV, Serres writes that:

SERRES: SCIENCE, FICTION, AND THE SHAPE OF RELATION My body [...] is not plungedinto a single, specified space. It works in Euclidean space, but it only works there. It sees in projective space; it touches, caresses and feels in a topological space; it suffers in another;hears and communicates in a third.... My body lives in as many spaces as the society, the group or the collectivity have formed.... Consequently,my body is not plungedinto one space but into the intersectionor junctions of this multiplicity. (Hermes 44-45)

43

In Les cinq sens, however, Serres expandsupon this philosophyof the body by statingthat it does not simply inhabitmultiplespaces; rather,it constructsits sense of itself through and in terms of a structuralmultiplicity. For Serres, bodies are always "corps meles" (mingled bodies). Using the skin (which he says carriesthe message of Hermes)as merely one example, Serresreveals how "in the skin, throughthe skin, the world andbody touch, definingtheir common border. Contingencymeans mutualtouching:world and body meet and caress in the skin.... I mingle with the world which mingles itself in me. The skin intervenes in the things of the world and brings about their mingling" (qtd in Connor, "MichelSerres'sLes CinqSens" 157). As Connorsuggests, knowledge is no longer a process of unveiling the world (157); rather, knowledge arrives both from being thrustinto the midst of things, from being implicatedin a world of relationshipswith objects and others that brings diverse local spatialities together, and from also understandingoneself as a similarly imbricatedand implicatedbundle of multiple relations. Strangely, for a thinkerwho so relishes being deridedas a poet and whose philosophicalmethodrelies so heavily on metaphorto give a rapidcontiguityto what would normally remain spatially distinct, Serres uses the embodied philosophy of Les cinq sens to cry out against language and "the empire of signs" that informedthe Westernintellectualand social dominantof the 1980s. Part of this refusal of language is a turning away from the discourse of phenomenology,which has a lineage thatlinks the poststructuralism Derrida of back throughHeidegger's fundamental ontologyto Husserl.9Serrestells Latour that the "returnto things" always runs up against the barrierof logic within philosophy; phenomenology, in particular, always filters sensory experience throughstructuresof language. He criticizes Merleau-Ponty'sassertionin The Phenomenology of Perception that "'we find in language the notion of sensation.' ... What you can decipher in this book is a nice ethnology of city dwellers, who are hypertechnicalized,intellectualized,chainedto their library chairs, and tragicallystrippedof any tangibleexperience. Lots of phenomenology and no sensation-everything via language"(132). But, as Connorpointsout, the final section of Les cinq sens reworksSerres's critiqueof philosophiesthatclose their ears to the sensible word and listen only to language, by renderingthe postmodernobsession with signs redundant rather than erroneous (166). Serres writes that ratherthan opposing the world where signs are dominant,his text "celebratesthe death of the word" (Les cinq sens 455), for the world of languagehas alreadybeen decentralizedandredistributed as part of a wider network of codes and information. As Connor puts it, "[wihere language [for Serres] sought to fix and petrify objects, distributing them in patternsof invariantconversionandexchange, information dissolves the

44

VOLUME (2006) 33 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES,

object by operationalizingit" ("Michel Serres's Les Cinq Sens" 166). A world that is conceived of according to the complex, unpredictableand turbulent circulationof information,ratherthan under the delimited arena of agreement that Serres problematicallysuggests is requiredby the exchange of signs, takes Serres back to "the primal adventureof philosophy ... the bottomlessmystery of the givenness of things, now, and perhaps just for now, apprehensible otherwise than as the mere task or antagonistof the linguistic subject-protagonist" (Connor, "Michel Serres's Les Cinq Sens"167). Most postmodem theorizations of the body have sought to emphasize its hybridity, its dispersal, its multiple interfaces with technologies-humanity as the apotheosisof Freud's "prosthetic god. " Serres's version of embodimentmay have none of the jacked-in enjoyments or prosthetic appendages of which theoreticalexplorers of cyberspacewere once so fond; nevertheless, it cannot be read as an agrarianrejection of technology or some nostalgic return to an essential and stable matter either. Instead, the processes through which the embodied subject feels, thinks, and constructs itself are shown to have been always alreadymultipleeffects of the dispersaland coagulationof information, the centripetaland centrifugalforces thatmake center and peripheryimpossible to locate and that are the sensory body's work of self-makingand self-transformation. The sensory body is not a coherentmodem subject, distinctive within anddistinctfrom its environment;it is a multiple, a bundleof relations-a quasibody, perhaps. Serres's distinctiveaccountof embodiment,his desire to figure the world as a network of relationships in which objects play constitutive roles, and his continuinginterest in the topologically complex passages between systems and disciplines, makes this work particularly relevantto contemporary texts thatare attemptingto explore the intersticesof the traditionalgenres of science fiction, horror, and fantasy. Sf's persistent attempt to impose a certain disciplinary purity on itself, most famously articulatedin Darko Suvin's assertion that the genre is constructedthroughthe "presenceand interactionof estrangementand cognition"(61), borrowsmuch from science's fundamentally modem claims for the impermeabilityof its borders. But where sf has traditionallybeen representedas a genre thatimaginesdifferentworlds, spaces, andtechnologieswithin the framework of rational laws of causality and logical possibility, China Mieville has recently sought to rethinkscience fiction as a "subsetof a broader fantastic mode" ("Symposium"43), suggesting that sf simply represents the "not-yet-possible"ratherthan the "neverpossible" that has more traditionally characterized fantasy. Serres's account of the mythological paratext and crumpled time-lines that run alongside the positivist narrative and linear temporalityof science is very suggestive for a readingof the "darkfantasy"of a writer such as Mieville. For this work, which has variously been called the "New Weird," "slipstream," "span," or "interstitial"fiction (see Luckhurst 241), can also be thought of as exploring the topological similarities and unexpected passages between areas of thoughtand genres that philosophyand literaturewould normallyhold distinct.

SERRES: SCIENCE, FICTION, AND THE SHAPE OF RELATION

45

M. John Harrison,who coined the moniker "New Weird" in homage to the WeirdTales of the 1920s that similarly combined science fiction, fantasy, and horror, suggests that such texts can "replaceboundarymetaphors... [and] get rid of the old Newtonian spatialmetaphorsof 'barriers'and 'ghettos"' (qtd in Luckhurst240). One must imagine that, as in Serres's work, such "boundary would be replacedby passages, conjunctures, connectivities.A short metaphors" story such as Mieville's "Reports of Certain Events in London" certainly translations exploresvarioushomeomorphic amongrealism, fantasy,conspiracy narratives, and the Gothic, as it describes how the narratoris drawn into a meticulously detailed occult science that explores the Via Ferae (feral streets) thatappearand disappearin London. As with Mieville's earlierKingRat (1998) and the Gothic Jekyll and Hyde, generic transgressionis figured in terms of topological complexity; but here, the very subjectof the narrativehas become the unpredictablepassage-the wild alleyway and untamed boulevard-that enacts a form of mythic spatialtranslation.One way of readingthis remapping of the corporate, institutional,and diversely social spaces of the city according to the wild and illegible logic of Via Ferae is to view it as a reworkingof the Situationistderive thatpays even closer attentionto the role of objects in the coconstructionof urbanspace. Partof what makes Mieville's work so compelling is the astonishingattentionhe gives to the world of things, as he imagines the city streets that are constitutiveof the social world as possessed with powerful but unreadableintentions: "Theirmotivationsare unimaginable,as opaque as brickworksphinxes. If they consider us at all, I doubt they care what's in our interests" ("Reports" 75). The text imagines urban space as transcribedand transfigured by the turbulent and chaotic appearance of these literalized prepositions, which occur like parasitical "patterns of interference" (59), constitutingand scramblingthe distributionof information that makes up the networkof relationshipsthat is London. The Via Ferae and the city itself might thus be imagined as quasiobjects-"multiple in space and mobile in time, unstableand fluctuatinglike a flame, relational"(Serres, Genesis 91)-rather than essential objects that are nothing other than tools to be used by powerfully coherent subjectivities. "VarminWay," which appears and disappearsin "Reports," is in fact both quasi-objectand quasi-subject:it intentionallypushes throughthe stable urban environment,but it is neverthelessreshapedby the city, as it sometimesappears in "abuckledconfigurationdue to the constraintsof space" (61). The Via Ferae, which are multiplein space and time, have their own unreadableintentions;but they can also potentiallybe used by humans.There are legends of those who can tame and ride these streets; but the Via Ferae are just as capable of using the humanbuilding and planningefforts throughwhich Londonis constantlybeing reconstructedfor their own purposes. "Maybethis is how they will occur now, arrivingnot suddenlybut slowly, ushered in by us, armouredin girders, pelted in new cement and paving" (77), suggests the narrator. Of course, Serres insists thatthis is how things generally are, thatthis is the quotidianexperience of embodimentand of being throwninto an object world; Mieville, in contrast, relishes the Gothic frisson at the presentationof what

46

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME (2006) 33

seems like monstrosity.In "Familiar,"a witch attemptsto conjurea powerful fetish for himself that will work as a "conduitto fecundity" (83). A visceral conglomerationof his own flesh and bodily fluids, the familiaris rejected, but grows by wordlessly incorporating everythingand anyone it encountersinto its own horrifying multiple and mingled corporeality. This "corps meles" is however still boundto its progenitorthatwished to use it as a tool; and it grows at the expense of the integrityof the witch's body, which fades away in "random holes" and "[e]ntropicwounds" (95). This is a singularly Gothic account of embodiment;but Mieville's fantasticallyimaginedcorporeality,combinedwith the supernatural power of the object world, uses the affective disturbances they enact as part of an explicitly political attemptto imagine and think outside of "realist"capitalistepistemologiesandontologies. Mieville assertsthatthe "New Weird" is a genre that both imagines and "is born out of possibilities, its freeing-upmirroringthe freeing-up,the radicalisation the world. This is postof Seattle fiction" ("Long Live the New Weird" 3). As Luckhurst notes, Mieville has recently extended this argumentto state that "Neoliberalismcollapsed the social imagination,shuntingthe horizons of the possible. With the crisis of the "WashingtonConsensus" and the rude grass-roots democracies of the movements for social justice, millions of people are remembering what it is to imagine" (qtd in Luckhurst 240). For Mieville, as for Serres, there are ungainsayable, constitutive relations between subjectivity and the world of others. But where Serresuses philosophyinflectedwith the tropesof fiction and poetry to mapthe intersticesof orthodoxaccountsof the world, Mieville fleshes out the role of a philosophicallyrigorousfantasyin imaginingalternativesto the accountof an empoweredmodernsubjectthatis distinctin andfor itself andthat representsthe world as a playgroundfor its projects. For Mieville, there is an enduring political significance in imagining a quasi-subject that remains separableneither from the object world nor from those other subjects that it would seek to objectify. Of Air and Angels. Theoristsof the postmodern have consistentlywrittenof the importanceof contingentepistemologies, of "situatedknowledges" (in Donna Haraway's terms) that refuse to speak globally in one stridentvoice. Serres similarly asserts the value of regional domains that do not circulate, as in the philosophicalsystems of modernity, "an autonomoustype of truth,"with each domainhaving "a philosophyof its relationsof its truthto its system and of the circulationalong these relations"(HermesII; qtd in Harariand Bell xiv). For Serres, there are only ever regionalepistemologies. However, as his work from the 1990s onwards makes clear, the task of philosophy now may be to pay attentionto the local, but only insofaras it reveals multipleand chaotic relations with the global. In a rathermore synthesizingfashion than previously, Serres writes thatbecause globalized telecommunications (de)materializea world that seems structuredas and throughexchanges of informationor messages more completely than ever before, it is possible and indeed necessary to write "a general theory of relations" (Serres and Latour 108). In the last chapterof Le Contrat naturel (1992; The Natural Contract) he meditates on the word

SERRES: SCIENCE, FICTION, AND THESHAPE RELATION OF

47

contract-literally, the connection,the cordthroughwhich "information, forces, and laws" (108) pass-and begins to see how, throughscientific progress, the bonds and relationsthatattachhumansto objects, to the earthand to each other, will need to be rethought.The first quasi-objectsconstructedthe social contract, but but thatcontract"comprehended a few objects, drawnby a modest number of members" (109). There was no totality of humans, just as "there was no nature, in the global sense of the word" (109). The modern social contract constructed around Enlightenmentscientific accounts of the world was also unaware of nature, "for the collectivity live[d] only in its history, and that history lives nowhere" (109). Nature was reduced to human nature. The world of globalized telecommunications,however, gives us new contemporary quasi-objects,new tools that link local to global. In Angels, and, more recently in Hominescence (2001), Serres explores how technoscience has produced conditionswherebythe world, reformedas both a multiplylocalized and global network of matter-information,requires that those traditionalcords be both detached and reattached in ways that bring metrically distant spaces into a topological contiguity. Serres goes on to write a book on angels because they are the airborne "message bearers"of the world of global telecommunications:"Each angel is a bearer of one or more relationships;... every day we invent billions of new ones." (Angels 293). Serres states in Angels, as he hints in The Natural Contract,that a particularsubsetof quasi-objectshas enabledthis volatilization of matter into message. These objects are what Latour calls "immutable mobiles," which, as Nick Binghamexplains, carryinformation reconfigure, and through the contractsthey create, the metrical spatialityof distant and near: "writing, print, paper, money, a postal service, cartography,navigation, and telephony have all generated new forms of immutablemobiles and (consequently) the potential for new configurationsof centres where they may be combined and peripheriesfrom which they may be gathered"(Bingham253). These "immutable mobiles" that "thinkfor us, with us, among us, and ... even within which, we think" (Angels 50), are not new. Serres insists that the "artificial intelligence revolution dates from at least as far back as neolithic times" (50), when we began to encounterquasi-objects.Nevertheless, because we now exchange increasingamountsof informationwith "objectsthat appear more as relations,tokens, codes andtransmitters" (52), becausewe interactwith quasi-objectssuch as computers, which break old contracts and produce new materialand social relationships,we are "living like angels" (62). We are able to function in multiple localities throughthe use of media that are no longer bound, as books, like "differentsheets, piled one on top of the other ... isolated in their own dimension.... [T]oday's interconnectednesspierces vertically throughthe stack, or punches throughbetween vertices, thus enablingthem to communicate" (68). This space of elsewhere, inside out-there, in which communication takesplace, is called in Atlas (1994) the "hors-la"-the multiple space of sensory experience, which also appearsin Les cinq sens. This space is, however, illuminated,renderedairborne, and translatedthroughgeographical space by telecommunications.

48

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 33 (2006)

It is becomingincreasinglyclear thattheoryis moving away from the overlytotalized versions of postmodernity, which kept such a strangleholdon the humanities in the latter part of the twentieth century, towards more flexible, more multipleaccountsof globalizationandthe global contemporary.Although Serres has shared certain kinships with the postmodern,a text such as Angels might also be seen as an attemptto considerthe relationsand linkageswithinthe global contemporary that bring together spaces and times other than the dominant.His text thus attemptsto do justice to andmap the relationshipsof the local to the global. In TheNatural Contract,Serres considers the way in which the network of global telecommunicationsinauguratesa new contractwith the earth in its totality-a symbiotic relationshipthat reveals our responsibilityto and for the naturalworld and makes it all too clear that the earththreatensour survival, as much as we threatenits: "Bound togetherby the most powerfulweb of communicationlines we have ever spun, we comprehendthe earth and it comprehendsus ... in an enormousplay of energies that could become deadly to those who inhabitthis contract"(110). Some of the frustratinglyeuphoricpanegyrics to the possibilities of global communicationin Angels are similarly tempered by Serres's concern for the exclusions and bonds that necessarily attend technological connection. The "angels" of the virtual community inhabit what Marcel Henaff calls the "telepolis" (187) and Serres calls "Newtown"-a sphere that floats above and is illegitimatelyopposed to the fourthworld, which is excluded from the world of telecommunications(Angels 59-78). Serres's suspicion of "the empire of signs" remainseven in this new world orderof expanded,turbulent,circulating information;for as Henaff rightlyobserves, for Serres "languagehas remained the best and the worst of things" (188). So there are importantquestions to be asked of the new contractsforged by quasi-objects:who stores, controls, and programs information; who is excluded from both the hardware and the software? Serres remains hopeful, however, that this newly networkedworld will make it harderfor the soundof the local to be drownedout completely. As Henaff points out (whilst reserving some doubt as to whetherthings will really turn out like this):

It has become not only useless, but irrational and even criminal to erase

in landscapes orderto insertthem in mass production, createindustrial to

conglomerateswhere work is Taylorizedand dwellings are stupidlyuniform, to destroy ancient cultures in the name of a technical and centralizingmodernity. Local spaces andculturescan easily find a way to become global by means of the network. (188)

Perhaps.It remainsto be seen whetherthe informationthat is fed into the global network from the third and fourth worlds will be heard as languageand sense ratherthan filtered out as inevitable static within the system. Some recent science fictions have also begun to pay attentionto this space of exclusion. Geoff Ryman's novel Air (2005) is an account of a village in the imaginedterritoryof Karzistan,the last in the world to go online. It concentrates on the introduction a new technology, "Air," thatoffers to bring the benefits of

AND THESHAPE RELATION OF SERRES: SCIENCE, FICTION,

49

of the Internetinto the nonspaceof the mindby formattingthe brainto interface with communicationstechnology. By doing away with the need for hardware, Air seems to evaporate the material problems of exclusion from the technologizednetwork. Despite exploringvariouspolitical anxietiesconcerning who controls these formatting structuresand the loss of indigenous cultural formations,the novel presentsAir as a fundamentally utopianpossibility. Ryman negatively articulates the problems facing an increasingly networked global society-exclusion from that network, the loss of culturalspecificity, the lack of connectionbetweenpeople who live in geographicalproximityto one another, the severing of the cord thatconnects people both to their location andpast-by finally renderingthem obsolete in the impossibleworld of Air. Air works in the eleven dimensions projected by contemporary string theory, which some physicists believe will offer a totalized explanation of the world; it thus mystically allows communionbetween all bodies and all souls, past and future. Air can speak, hear, and see for the protagonistMae's burnedand profoundly disabledbaby, placinghim withinan infinitelyaccessible networkof others. The final vision of the novel also brings the warring factions of Mae's extended communitytogether as they "[turn]and [walk] together into the future"of Air (390). It could be arguedthat this utopianismcritiquesjust how far the present networkof communicationsreally is from being either truly global or infinitely accessible; but there remains an unexamined assertion that the free trade in which Mae is now able to take part can simply evaporate social and cultural exclusion. Of course, there is also a political problemin imaginingthe space of thirdand fourthworlds as a new territory,a new world, thatenables first-world writers of sf to explore, in brightly colored relief, their own anxieties about technologicalchange. And perhapsit will become more significantin the future to listen to the ways in which culturesthatare newly assuminga place withinthe networkof global communications begin to write andimaginethese reconfigured relationshipsin their own fictions of science. Michel Serresremainsan authentically perversethinker,in the sense thathis work represents a fundamental and productive deviation or swerve from philosophies of modernity. He is not interested in Habermasian rational communication dialogue, in the notion of history as progressor even regress, or nor, more fundamentally,in the separationof the social and naturalinto neatly separable categories that Latour sees as a fundamentalpart of the modern settlement.For the amodernSerres, the multiple, turbulentspace of the relation between objects andhumans, the planetand its inhabitants,is philosophy'svital task to explore, just as it has been science fiction's role to map and describe. In a world that materializes itself more and more as exchanges of information within plural and chaotic networks, Serres thus attempts,not always successfully, to do justice to the complexity of the relation without writing out the scenes of local and global injustice. Serres representsthis technologizedworld, as many sf texts have done, as a space and time of desire and fear, hope and terror. Serres's work may be useful for sf studies, however, not simply because it offers another theoretical language with which to describe the global contemporary;instead, it offers, more fundamentally,a way of reading the

50

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 33 (2006)

space between humans and others, between discourses, between science and fiction, as a passage of productiveandunpredictable exchangein which both the message and the untranslatable static can, momentarily,be heard.

NOTES 1. Serres does not dismiss Newton's theories, but he seems more interestedin how his system of "reverberation" partiallyreprisestheoriesof Lucretianturbulence(Natural Contract 108-109). 2. As Serres points out to Latour, the French language preserves the connection between time and weather systems by using the same word to indicateboth: les temps (58). 3. The five volumes of Herme'shave not yet been translatedinto English in their entirety; the single-volume anthology Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy, edited by Harariand Bell, contains selected chaptersfrom all five volumes plus a section from La Naisance de la physique dans le texte de Lucrece: Fleuves et turbulences(1977; The Birth of Physics). For ease of reference, all citations from Hermes derive from the translatedsections in Harariand Bell's anthology. 4. Serres tells Latour that he knows structuralismwell, since it is "algebraic in origin" (35). Serres's first degree was in mathematics. 5. Cavallaro also notes that "the Gothic and cyberpunk inaugurate an "anarchitecture" confuses the conventionalseparationbetween inside and outside, that challenges the codes of perspective and underminesthe very foundationsof Euclidean geometry" (177). 6. Nick Bingham notes the extent to which Gibson's work has influenced the formulationof problems and the agendaof researchinto cyberspace and virtual reality in both science and the humanities(248-49). 7. Serres makes a connectionbetween the enormouscost incurredby both societies in erecting such "statues,"the key effect of specialists(scientists/priests)in constructing and controlling the event, the shared goal of reachingthe heavens, and the importance of performancein front of watchingcrowds. Serres uses these similaritiesto argue that our technology contains repressedarticulationsof atavistic violence. 8. The English translationof this text will be publishedin 2006. 9. Serres tells Latourthat he "respect[s]"philosophiesof language-"I recommend them to my students,I have even practicedthem"-but that he finds the results obtained to be "fairly weak" (Serres and Latour 131). He will not be drawn by Latour on the relationshipof his work to Derrida's. He simply states: "I have never participated the in Heideggerian tradition" (38). See also "The Stylist and the Grammarian"in The Troubadourof Knowledge (English translationof Le Tiers-instruit)for more on the relationshipof Serres's thoughtto Derrida's. WORKS CITED Berressem, Hanjo. "'IncertoTemporeIncertisque Locis': The Logic of the Clinamenand the Birth of Physics." MappingMichel Serres. Ed. Niran Abbas. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2005. 51-71. Bingham, Nick. "UnthinkableComplexity: Cyberspace Otherwise." Virtual Geographies: Bodies, Spaces, and Relations. Ed. Mike Crang, Phil Crang, and Jon May. New York: Routledge, 1999. 244-62. Cavallaro, Dani. Cyberpunk and Cyberculture.London: Athlone, 2000. Connor, Steven. "Topologies: Michel Serres and Shapes of Thought." Anglistik 15 (March 2004): 105-17.

SERRES: SCIENCE, FICTION, AND THE SHAPE OF RELATION

51

"Michel Serres's Les Cinq Sens." MappingMichel Serres. Ed. Niran Abbas. Ann Arbor: U of MichiganP, 2005. 153-69. Gibson, Andrew. "Serresat the Crossroads." MappingMichel Serres. Ed. NiranAbbas. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2005. 84-98. Gibson, William. "Burning Chrome." 1982. Burning Chrome, and Other Stories. London: Voyager-HarperCollins,1995. 195-220. . Neuromancer. 1984. London: Grafton, 1986. Journala plusieurs voies." Hermes: Harari,Josue V. and David F. Bell. "Introduction: Literature,Science, Philosophy. By Michel Serres. Ed. Harariand Bell. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1982. ix-xl. Henaff, Marcel. "Of Stones, Angels, and Humans:Michel Serres and the Global City." MappingMichel Serres. Ed. NiranAbbas. Ann Arbor:U MichiganP, 2005. 170-89. Luckhurst,Roger. Science Fiction. Cambridge:Polity, 2005. " Mi6ville, China. "Familiar. Lookingfor Jake, and OtherStories. London:Macmillan, 2005. 79-96. "Long Live the New Weird." The ThirdAlternative35 (Summer2003): 3. of ("Reports CertainEvents in London." Lookingfor Jake, and Other Stories. London: Macmillan, 2005. 53-77. . "Symposium:Marxismand Fantasy." Ed. China Mieville. Historical Materialism 10.4 (2002): 39-316. Ryman, Geoff. Air (or Have Not Have). London: Gollancz, 2005. Serres, Michel. Atlas. Paris: Editions Juillard, 1994. . Angels: A Modern Myth. 1993. Trans. Francis Cowper. Ed. Phillippa Hurd. New York: Flammarion, 1995. . TheBirthof Physics. 1977. Ed. David Webb. Trans. JackHawkes. Manchester: Clinamen, 2000. Le cinq sens. Paris: Hachette, 1998. Feux et signaux de brume:Zola. Paris: Grasset, 1975. Genesis. 1982. Trans. Genevieve James and James Nielson. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1995. . Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy. Ed. Josue V. Harariand David F. Bell. Baltimore:Johns Hopkins UP, 1982. Hermes I: La Communication.Paris: Minuit, 1969. Hermes II: LI'nterference.Paris: Minuit, 1972. Hermes III: La Traduction.Paris: Minuit, 1974. Hermes IV: La Distribution. Paris: Minuit, 1977. Hermes V: Le Passage du nord-ouest. Paris: Minuit, 1980. Hominescence:Essais. Paris: Le Pommier, 2001. Jouvences sur Jules Verne. Paris: Minuit, 1974. "JulesVerne's StrangeJourneys." YaleFrench Studies 52 (1975): 174-88. TheNatural Contract. 1990. Trans. ElizabethMacArthur William Paulson. and Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1995. . TheParasite. Trans. LawrenceR. Schehr. 1980. Baltimore:JohnsHopkinsUP, 1982. . Rome: TheBook of Foundations.Trans. Felicia McCarren.Stanford:Stanford UP, 1983. Statues:Le second livre des fondations. Paris: Flammarion, 1989. TheTroubadour Knowledge. 1991. Trans. FariaGlaserandWilliam Paulson. of Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Press, 1997.

52

SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 33 (2006)

and Bruno Latour. Eclaircissements:cinq entretiensavec Bruno Latour. Paris: Flammarion, 1994. Trans. as Conversationson Science, Culture,and Time. Trans. Roxanne Lapidus. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1995. Stevenson, RobertLouis. TheStrangeCase of Dr Jekylland Mr Hyde. 1886. New York: Norton, 2003. Suvin, Darko. "Onthe Poetics of the Science Fiction Genre." Science Fiction: Twentieth CenturyViews. Ed. Mark Rose. New York: Prentice Hall, 1976. 57-71. "Topology." The Compact OxfordEnglish Dictionary. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1989. 2081. ABSTRACT This article offers a synoptic introductionto the thoughtof Michel Serres and suggests how his work might be used to read science fiction. Serres's intensely topological form of analysis explores the complex relationshipbetween realms that are normallyheld to be distinct within modern thought, such as science and fiction, mathematics and mythology. The article argues that such a topological method offers sf studies a theoretical language for mapping its own generic transgressions;it also suggests that topology can be used to readthe disturbinglycontinuouscognitive andimaginativespaces found at once in the Gothic and in cyberpunk.The article goes on to argue that Serres's lateruse of informationtheory, alongsidehis conceptof the quasi-object,opens up a way of reading the topologically complex relationshipbetween embodiment and objects, subjectivity and the world of social relations, found in the work of China Mieville. Serres's most recentwork on globalized telecommunications explores the ungainsayable social bonds within this network of quasi-objects, articulatingthe vital relationship between the local and the global. Exploring Serres's accountof quasi-objectsthat reads technological communication as constitutive of a philosophically reconfigured intersubjectivity,the article finally uses this work to read Geoof Ryman's recent novel Air (2005).

You might also like

- Flesh. Toward A History of The MisunderstandingDocument14 pagesFlesh. Toward A History of The MisunderstandingRob ThuhuNo ratings yet

- Serres - The Science of RelationsDocument13 pagesSerres - The Science of RelationsMonika HalkortNo ratings yet

- Traces of Identity in Deleuze'sDocument21 pagesTraces of Identity in Deleuze'sVissente TapiaNo ratings yet

- Michel Serres on Disasters, Technology, and the UnforeseenDocument6 pagesMichel Serres on Disasters, Technology, and the Unforeseenpaulotavares80No ratings yet

- Alexander Galloway Laruelle Against The Digital PDFDocument321 pagesAlexander Galloway Laruelle Against The Digital PDFDerek Boomy PriceNo ratings yet

- Sluga, Hans D. Frege's Alleged Realism - 1977 PDFDocument18 pagesSluga, Hans D. Frege's Alleged Realism - 1977 PDFPablo BarbosaNo ratings yet

- SERRES Parasites As Agents of ChangeDocument2 pagesSERRES Parasites As Agents of ChangekellycigmanNo ratings yet

- Lacan's Complex Topology of Psychoanalysis and ScienceDocument33 pagesLacan's Complex Topology of Psychoanalysis and ScienceMarie Langer100% (1)

- Psychoanalysis and Post HumanDocument22 pagesPsychoanalysis and Post HumanJonathanNo ratings yet

- Non-Phenomenological Thought, by Steven ShaviroDocument17 pagesNon-Phenomenological Thought, by Steven ShavirokatjadbbNo ratings yet

- Museum as refuge for utopian thoughtDocument6 pagesMuseum as refuge for utopian thoughtaliziuskaNo ratings yet