Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ethical Issues in Palliative Care

Uploaded by

Nugraha Dwi Ananta RNOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ethical Issues in Palliative Care

Uploaded by

Nugraha Dwi Ananta RNCopyright:

Available Formats

Ethical issues in palliative care

INTRODUCTION Ethics may be considered by some to be a dry theoretical subject that has little relevance to, or at best is remote from, patient care. an the contrary I would suggest, and hope to illustrate within this chapter, that ethical issues are extremely relevant to palliative care. The chapter commences with an illustration of how a relatively simple aspect of patient care may challenge the ethical permissibility of actions depending on the values held by the carer. The reader is invited to . reflect on this and, drawing from their personal experiences, to identify similar occasions where ethical dilemmas arose in clinical situations. The chapter sets out two key philosophical approaches consequentialism and deontology that have influenced the values and morals of Western-based societies and cultures. Key ethical principles related to health care are introduced, which provide the basic building blocks from which the ethical permissibility of potential dilemmas may be explored. These principles, together with other tools used in ethical clinical decision making, enable health care professionals to determine whether clinical actions or decisions about care are ethically justifiable. Finally, current issues in palliative care are explored, focusing particularly on the subject of extraordinary and futile care towards the end of life. The reader is encouraged to actively reflect on the ethical component of these issues and on their personal views. By removing emotional reactions to issues and by reflecting on both personal values and the ethical principles involved in the issue, the reader should be able to objectively examine the ethical permissibility of clinical actions within palliative health card. Far from ethics being a dry subject, it is anticipated that the reader will be drawn into constructive, informed critical argument and debate, bringing alive the ethics within palliative care.

THE MORAL PICTURE The provision of health care is becoming increasingly complicated by the expectations of a society which is better informed about current treatment options and has high demands and high expectations about the health care provided. The focus of palliative care, by its very definition, looks towards multi-professional holistic care provision Wowing recognition of no potential cure. This places an emphasis upon individual preferences in determining the quality of life. The subjective issues that arise should be considered on an individual basis, and should be recognised as reflecting values that are the essence of individualised care. In attempting to provide appropriate care, health care professionals may find conflict between their assessment of the needs of the patient and their family, the interventions deemed necessary by both parties, and in determining objectively the general subjective priorities that individuals place on their own value and quality of life.

In general, ethics can only provide an indication of the general ethical permissibility or acceptability of actions. If carers respect even the most fundamental principles of ethics, the autonomy of the individual patient should be respected; this is balanced by the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. However, decisions that are arrived at result in implications for our society in general and, as such, the ethical permissibility of care for individuals needs to be tapered by the implications for the ethical implications of similar situations within our society -the nation of the principle of justice. Ethical issues that arise in palliative care may be recognised as being similar to those in other specialties. Common examples include issues effecting the professionalpatient relationsh. resource allocation, truth-telling, confidential respect of individual and professional autono7 consent to and refusal of treatment and the w1:- holding and the withdrawal of treatments at b. - the macroand micro-level within palliative c:.-: All too frequently palliative ethics is mis: enly focused on the debate surrounding eu:: nasia. The reality is that the nature of the V concept of palliative care, particularly within hospice network, excludes the euthanasia deg in that palliative care by its very definition riot intentionally hasten, shorten or unnecessa - prolong the end of life of those in receipt of c. ity palliative care. Palliative care cannot there:: include the deliberate ending of life within objectives, whether it is actively or passi-a sought, either voluntarily or non-voluntarily. Palliative care continues to be challenge,: recognising the extent and alleviating the ual, psychological and social symptoms in a r tion to the ongoing relief of physical nee:. Regrettably, at times, carers and families bec, -the reluctant observers of inadequate sym control, where suffering, distress and - become unmanageable by the multi-profess: team. At these times it is possible to beg is understand the view of some who place value on their lives not to wish to exper such distress, and would prefer to shorten IT natural lives. This brings up the emotive sc of passive voluntary euthanasia

ETHICAL ISSUES IN PALLIATIVE CARE While these issues may be similar to those experienced in other health specialties there exists a unique edge to some ethical dilemmas in the specialty of palliative care. The very nature of palliative care focuses debate about ethical issues on the inevitable death of the person. Circumstances at the end of life may result in ethical dilemmas being further complicated by issues concerning the competence of the dying person, their right to refuse or accept care and in maintaining their personal integrity over their own death. Ethical dilemmas may arise from differing values

placed upon the value of life by both patients and their carers. Dilemmas may also extend to circumstances surrounding resource distribution: do dying people have the right to access every possible treatment whatever the cost in terms of finance, time and available resources? It would appear that palliative care has a unique set of ethical situations that challenge the multi-professional team, the patient and their families to determine ethically permissible courses of action. In bringing comfort and hope to patients and their families who are in need of quality palliative care, multiprofessional health care teams are frequently challenged by decisions that need to be made depending on the circumstances at a particular time. Potential influences on these decisions can be seen in Box 14.1.

The influence of the laws of individual states on ethical decisions determine the legal rightness or wrongness of actions, not necessarily their moral ethical permissibility. This situation is clearly illustrated by the issue of assisted suicide where the law determines the legality of such actions (whether the action or omission is ethically permissible or not). This is illustrated by assisted suicide being currently illegal in the UK; a very grey area in Holland (being nonlegalised, but not appearing to be legally punished by society); being legalised and then overturned in the Northern Territories in Australia during the late 1990s; and being legal (given specific circumstances) in the state of Oregon in the United States where one can apply to have a prescription for medication to end one's life (the safeguards of this are controlled through strict criteria including a 'cooling off' period in case the subject changes their mind!). Those who work in palliative care may understand the wishes of patients who wish to die peacefully and with a quality of life whose acceptability can only be determined by the patient themselves. In some situations patients may value an early end to their lives. While perhaps not agreeing with some practices, it is a compassion of understanding that health care professionals are required to develop in such circumstances, respecting the autonomy of the individual's wishes. For a simple example of an ethical dilemma in palliative care consider the concerns about truth-telling. Consider the hypothetical scenario shown in Case study 14.1. Consideration of ethics may not provide the answer to all the difficult questions that can arise in palliative care. Frequently, there is no clear right or wrong, black or white side to a clinical situation, only a greyish state of affairs that appears to change depending on the way the overall picture is perceived. What ethics does allow for is specific argument to be made about the circumstances surrounding individual cases which looks to answer the question, not of whether the result is essentially right or wrong, but whether it is ethically permissible. In ethics the emphasis must be regarded and thought of in terms of the ethical permissibility of

actions or inactions. An awareness of ethical issues and arguments enables practitioners to come to informed decisions about their actions and to help clarify situations for patients and their families. The challenges faced by health care professionals within palliative care are frequently focused around specific ethical issues at the end of life (Fig. 14.1), such as decisions relating to the continued provision of artificial hydration, certain drugs and artificial feeding. These are in addition to the general issues that commonly affect most clinical specialties as well as palliative care. Ethics can provide a basis to determine whether decisions made about care, treatments or withholding treatments can be ethically permissible. Decisions are complicated further when a patient's personal autonomy is reduced. This can occur when the patient may no longer be able to indicate their personal preference as a result of drugs, a progressive deterioration of their consciousness or through any disease process that restricts their ability to understand, to deliberate or to communicate their wishes (or any combination of these). In such circumstances, consideration of actions that would be in the best interests of the patient need to be determined. This can be facilitated through discussion with close family members or, in, their absence, the multi-professional team providing the care. Difficulties can arise through conflict amongst immediate family or team members when, as individual people, they have differing values about issues at the end of life. Even during the provision of palliative care during the early stages of a disease process there are difficult decisions to be made about the provision of expensive treatments. Such resource allocations are not just linked to individual treatments but to the decisions made by Trusts and Health Management Executives about till' provision of certain long-term treatments (e.g. a particular d treatment available for patients with multiple:= rosis which may not be available in all parts of _ country). Equally, the preferences of patients to . within their home environment maybe restric:_-: by the local availability of appropriate care in - community, or the availability of local palliat: units within remote rural areas, which necessity.-: family members having to travel large distance a time when they may be increasingly vulnerab. The CalmanHine (1995) report went so-- way to recognising the need to achieve equa:: in the availability and provision of cancer c~- and, as a consequence, palliative care across country. Such initiatives are to be applauded, 17 - must be continually acted upon to maximise benefit ,to patients who require palliative ca-: regardless of the nature of the cause. The ethics around euthanasia can be deb:: from many angles, both for and against. In:_viduals need to decide what they feel is ethica:: appropriate. However, while

defending the ri,:_of individuals to self-determination, it may no:f ethically appropriate to request that somet,-.: assists in the death .of a person if they are not v.-. ing to do so, or if it challenges the professio7.1. code in which they work, or if it challenges legal circumstances in that country. The conceh: euthanasia takes many forms: voluntary or _ - voluntary, passive or active. In Utopia, all syr. --toms in palliative care could be addressed, not just the physical but the psychological, social and spiritual. In reality, health care is only able to meet some of these admirable goals; but in striving for them practitioners should never lose sight of the individual patient and his/her family. Guidelines from The National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services (NCHSPCS) focus on the non-acceptance of voluntary euthanasia (NCHSPCS 1992,1997a). These guidelines should be adhered to by those involved in palliative care; however, practitioners should be aware of the ethical arguments that underpin both sides of this emotive issue, and, as the NCHSPCS guidelines do, recognise the right of the individual to request to be allowed to hasten death, or to refuse treatment that results in the hastening of death.

ETHICAL THEORIES Two differing but highly influential ethical theories have influenced the morals of current society. Together with key ethical principles that influence current health care provision, these factors form the basis on which the ethical permissibility of clinical decisions across health care, and in particular palliative care, are based. An ethical approach to determining whether actions or inactions are ethically permissible, which includes consideration about the quality and the value of life and death, should in turn bring comfort and hope to patients and their families. In considering clinical decisions or dilemmas there are several ethical approaches that can be used. The two key theoretical approaches that are introduced in this chapter reflect a duty-based approach deontology, and a con-sequence-based approach consequentialism. Deontology Approaches that involve basing decisions according to a duty that follows certain rules which should always be adhered to, whatever the circumstances, are known as deontological approaches. These approaches resolving ethical dilemmas stem from the work of Kant, and rely upon individuals adhering to specific 'rules'. Actions or inactions are considered to be ethically unacceptable if these are contravened. Kant refers to these 'rules' as categorical imperatives which must apply in all situations they are universal. These include 'rules' of not killing and of telling the truth. Problems for deontological approaches to health care arise when the truth can cause harm. to the patient or their family or in providing treatment that might have a foreseeable side-effect of harming or ending the life of a patient.

Consequentialism Alternatively, decisions may be based on the potential consequences of one's actions, which is consequentialism. Consequence-based ethical approaches are concerned solely on making decisions depending on the consequences that occur from the actions of the decision. Consequentialist approaches to ethics have developed from the utilitarian theories of Mill and Bentham. Their aim is that actions or inactions are ethically permissible where they maximise benefit or minimise harm as a consequence. As such, certain actions may become ethically permissible even if it means that certain 'rules' have to be broken. For example, a consequentialist could argue that it is ethically permissible to hasten the end of the life of a person if the consequences of that action would be to maximise the benefit for the person involved and perhaps for many others. There are two types of utilitarians: act utilitarians and rule utilitarians. The former would always act by considering the good and bad consequences in each particular set of circumstances; the latter would resolve to follow actions based on determining the consequences In similar circumstances. While consequentialist approaches to decision making can appear advantageous to some, the difficulty with determining the ethical permissibility lies in the determination of what constitutes 'happiness and harm'. For some people happiness may be derived from harm. The actual measure of the amount of 'happiness' may cause difficulty in determining the overall consequence of our actions. What may maximise benefit to one person may only be a minor happiness to Should one person have it all and consequent.A have a maximised benefit or should that give: benefit be distributed amongst the many to ma-imise the overall benefit for everyone? Equal:: what happens when an individual's happiness . dependent on the harm caused to another perso7 These difficulties with a consequent:: approach to resolving whether actions are et:-cally permissible are inherent in the manner which health care is distributed amongst popu:: -tions, the allocation of resource to particu :. -health care specialties, and how individu health care professionals allocate their time .. meet the needs of individual patients. Howe\ : -the goal of all health care professionals should to maximise the benefit of their care for indi~ uals, which reflects a very consequent:3. approach to health care delivery. Other ethical theories exist and have their ov. - particular approach to resolving moral diffia:.ties; however, it is the above two that health ca professionals frequently come across in dete:mining the ethical permissibility of their action., RIGHTS AND DUTIES Some approaches to ethics focus on spec]: rights, particularly the right of the autonome: - individual and the principle of respect for th..: -autonomy. It is from this style of approachi:- dilemmas that the argument for the rights of t~. individual to selfdetermination are derive:. While at times presenting a strong argument t~ difficulty

lies in that all individuals, includi:health care workers, have equal rights; problen-..~ occur when those rights are in conflict. There is some argument that there exists a 'du: of care' from the health care professional to t: patient. This would include respecting the indivic.uality of the patient and their privacy, to prever - harm occurring to the patient, and to be consulter and give information on which the patient can co:-sent to treatments. Professional bodies are require: by law to maintain professional registers of thou 'licensed' to practice. The United Kingdom Centre.. Council for Nurses, Midwives and Health Visite:, additionally set a Professional Code of Conde, (UKCC 1992) that outlined the expectations place on the professional nurse, more or less determining the duty of care that the nurse should provide. Registers for other professionals identify similar 'duties' within their codes of practice. Such codes of practice reflect a duty-based approach to the provision of health care, setting the parameters by which professionals are duty-bound to provide care for their patients. When clinical-based dilemmas result in conflict between these dutybased guidelines and the consequential approaches of others to care, then individual professionals may feel confused. At least this confusion indicates an awareness of the potential for conflict, indicating a questioning profession ready to challenge the sacred cows of practice for practice's sake. The duty of care appears to suggest that there is an ethical obligation to provide the best care, but how can the best available care be determined? Is the caregiver more obligated ethically to provide care that benefits patients or not to provide care that might do them some harm. Is there a greater obligation to remove a hazard that would otherwise certainly cause a harm to your patient or to provide care that does the patient some good? One may feel ethically obliged to do both, but what if one only has the time and resources to do one thing which is the greater ethically permissible action? PRINCIPLES OF HEALTH CARE ETHICS Within health care there have been widely accepted principles from which the ethical permissibility of actions may be determined. Individual and collective actions are considered as to how they respect ethical principles and in doing so assist to determine whether the actions or inactions are ethically permissible. Beauchamp & Childress (1994). identify the four ethical health care principles as: respect of autonomy beneficence non-maleficence justice.

It is these principles that underpin the ethical permissibility of health care provision. In addition to these accepted principles, Randall &

Downie (1996) originally argued for the inclusion of two further principles that warrant consideration in palliative care; these are: compassion utility.

The latter principle is added by Randall and Downie in recognition of the ethical problems faced by professionals in resource allocation, where utility is concerned with maximising of outcomes or preferences. Compassion, they argue, enables practitioners to gain an insight into the needs and situations of others. In discussing this, they conclude that compassion could not take precedence over other principles but it remains an essential supplement to them. The problem in accepting Randall and Downie's additional two principles, while acknowledging their desirability in palliative care ethics, is that they tend to confuse the moral picture being argued. Compassion may well supplement the principles and provide insight into others' feelings; however, this should be accounted for in the principle of respect for autonomy, while the principle of utility is encompassed by the principle of justice. To consider the two additional principles as fundamental health care ethical principles in their own right, equating them with other perhaps stronger principles, may lead to added confusion in determining the ethical permissibility of actions. These principles of health care ethics provide the foundations on which palliative care issues can be discussed from the perspective of either a deontological view (imposed by many professional regulatory bodies and employers within health care) or a consequentialist view (often taken from the personal perspective of the patient and their family). CLINICAL DECISION MAKING IN PALLIATIVE CARE Consideration of ethical principles may indicate the ethical permissibility of actions or inactions, which should be respected by the multi-professional team. The importance of making ethically permissible clinical decisions can often lead to conflict depending on the particular philosophical viewpoint that individuals hold. Within palliative care, difficult decisions are made which could be considered to result in the foreseeable consequence of hastening the death of the patient or even of unnecessarily prolonging it. Actions within these decisions need to be ethically permissible. Clinical decisions at the end of life can involve ethical considerations of actions and omissions; killing and letting die; heroic and extraordinary means of treatment; futile treatment, withdrawing treatments, withholding treatments and the doctrine of double effect. This is in addition to the duty to provide basic care that is required of all health care professionals. A consequentlalist clinician may consider that a greater good might come from the premature death of a person as a result of an action intended to benefit the individual in the short term, if this was what they wanted, and where continued living would

incur further harm to that individual and to others involved in their daily care. This would pose difficulties for deontologists whose maxim of not killing prevents notions of early death, regardless of the consequences that may follow. In ethical decision making, a tool that assists deontological clinicians who need to take actions that they can foresee will cause a harm to a patient (e.g. the use of palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy where a benefit for a patient might be obtained but with some unpleasant side effects) is called the doctrine of double effect (DDE). The DDE is a tool that determines that when four specific criteria are met the foreseeable consequences of some actions are ethically permissible. Twycross (1999) summarises the tool effectively but in so doing loses some of the significance and implications of the third and fourth conditions. The doctrine of double effect The doctrine of double effect suggests that, given certain conditions, one may not be responsible for the foreseeable effects of actions if they are not intended. The doctrine sets out four conditions that have to be met in order to determine whether the intentional actions are morally permissible despite some foreseen consequence. These conditions are. 1 What is done must be, at the least, morally permissible. 2 What is intended must only include the good any: not the bad effects of what is done. 3 The bad effects must not be the means whereby the good is brought about. 4 There must be proportionality between the good and bad effects of what is done. (Campbell & Coilinson 1988, p. l;: It is for this reason that Harris (1985) delights suggesting that the doctrine of double effect 'sophistry' enabling deontologists to be able adopt consequentialist values. The responsibility of one's actions woul: appear to depend on the particular argument- that one utilises, particularly with respect to tloriginal intention and to the proportionality of tl-_ consequences. While the DDE indicates morr . permissibility for a particular action it does n suggest whether a particular course of actic - should be followed at all times. The argumc-favouring the prescribing of these treatments that it becomes morally acceptable as long as t~. intended effect of the treatment is solely to trcs. the symptom, reducing the suffering. A forest: able consequence of the treatment is a potential. undesirable effect that may result in the prem.:: -ture death of the patient, but this is not the into: -tion of the original action. This is a classic exams of the use of the DDE to justify morally what o,-ers may argue is the intentional killing of a persc:

Issues that influence the balancing of right ar. wrong at the end of life require consideration what makes life meaningful and purposeful, a~..: hence valuable. If life is valuable then it become', wrong to end it prematurely. Recognition show:.: be given to the fact that in palliative care th process of dying combines both the concept of quality living together with the impendir. prospect of one's death. That which makes valuable for the individual can become increa,ingly worthwhile towards the point of death. T aims of palliative care encompass this. What ce-tributes to the quality of life for some people ma be seeing a distant member of the family; for ti -ers, attending a performance of an artistic piece work; for some, it is to set their affairs in order; ar.: for others, it is being able to still walk to the toilunaided. The aspects that contribute to a quality of life are of subjective individual determination. At some stage in palliative care a decision has to be reached about the care that should be provided. Decisions should involve, whenever possible, the patient, health care professionals from the multidisciplinary team and the relatives. Each individual has information and opinion which inform the best possible course of events for the individual concerned in order to provide the best possible circumstances that meet the individual's quality of living as they are dying. Health care professionals often want a predetermined checklist of quantifiable qualities that suggest an appropriate standard of living. Consequently, where the quality of life appears to be minimal or where total suffering becomes unbearably protracted, the issue of death appears to be an increasingly attractive proposition for some. These decisions are, at best, difficult to make, but the resultant actions should always be ethically justifiable. In the current climate, advancing medical technology and the associated escalating costs of providing treatments might be an added complication in that death could be an appropriate option if the cost of continuing treatments would deprive others of health care that enables them to have fuller lives. In the ideal financial health care service, this should never be a consideration in determining the ethical permissibility of decisions. Decisions that result in hastening the point of death must be challenged by a strong universal prohibition of the killing of patients that stems not only from the duties and responsibilities of health care professionals but from the legal and moral values that are held within society. In circumstances where there are difficult issues that need resolving or further clarification, there could be a case for employing clinically based health care ethicists who would be available to consult and advise over particular issues.

Acts and omissions Traditionally, it would be considered morally preferable to omit to provide a care that resulted in harm, rather than acting in a manner that invokes a harm. Rachels (cited by Glover 1977) contends that there is little difference between actions and omissions. He illustrates this using an example of two cousins who stand to inherit

substantial amounts on the demise of their third cousin. They plot to end the life of the third cousin. In the first scenario, one cousin enters the bathroom with the intention of drowning him and subsequently drowns his third cousin the action. In a second scenario the other cousin enters the bathroom with the same intention but sees the third cousin slip, knock himself unconscious and disappear under the bath water (it was a big deep bath!) he remains in the room but takes no action to intervene with the result that the third cousin dies. Rachels contended that there is no moral difference between the action or the omission and that we are equally responsible for both actions and omissions. There is no difference between the ethical permissibility of actions or omissions to care. This has particular relevance to palliative care, especially where treatments are gradually removed towards the end of life (NCHSPCS 1997b), and in particular is applicable to the situation of providing hydration at the end of life either by withdrawal or non-commencement of interventions. Perhaps the greatest significance of this argument is that, if what Rachels contends is acceptable, then similar argument suggests that if there is no difference between actions and omissions then there can be no arguable difference between killing and letting die. In palliative care this suggests that it would be equally ethically permissible not to give treatments knowing a patient would die, and there would be no moral difference between this and deliberately J ending the life of the patient. This lays a serious challenge to palliative care principles There carers are unable to take actions or omissions that hasten death, but who work in a culture where it is accepted in specific situations just to provide basic care and allow (let) the patient die.

The role of the nurse in ethical decision making In making ethical decisions the nurse needs to be aware of key ethical principles, the values that influence the approach to ethical issues and the tools used to justify decisions. The nurses have a role in ensuring there is common understanding and respect of the ethical principles affected by actions, and to constructively debate against issues that would not otherwise be ethically permissible. While doing this the nurse has a key role in promoting the autonomy of the patient if they are unable to do this for themselves, or if part of their competence is eroded, and in keeping the patient informed about decisions involving them if the patient wishes to know. Nurses need to utilise their knowledge about the principles of ethics, awareness of own values and those imposed on health care practitioners and only to give consideration to nursing interventions where the justification of the care offered should be ethically permissible. Being aware of differing theories the nurse is better prepared to come to a balanced and informed decision. Nurses are accountable for their actions; ignorance would not be a defensible justification should a harm be incurred by the patient when

action or omission was caused by nurses. It becomes a question of whether care given or care omitted is ethically justifiable; this is instigated by the issues raised by extraordinary and futile care.

You might also like

- Improving The Quality of Care in An Acute Care Facility Through RDocument88 pagesImproving The Quality of Care in An Acute Care Facility Through RNor-aine Salazar AccoyNo ratings yet

- Counselling, Breaking Bad NewsDocument26 pagesCounselling, Breaking Bad NewsArief NorddinNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Literature Review On Post Organ Transplant Mortality Due To Renal Failure: Causes and Nursing CareDocument18 pagesAn Integrative Literature Review On Post Organ Transplant Mortality Due To Renal Failure: Causes and Nursing CarePATRICK OTIATONo ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing PDFDocument5 pagesEthical Dilemmas in Nursing PDFtitiNo ratings yet

- WP Leadership StandardsDocument44 pagesWP Leadership StandardsIfrah Harun100% (1)

- Law of Delict PPPDocument22 pagesLaw of Delict PPPPragash Maheswaran100% (3)

- AOA Survival Guide To The 2nd YearDocument18 pagesAOA Survival Guide To The 2nd Yearmediquest100% (1)

- Corruption and Abuse of Office by PublicDocument13 pagesCorruption and Abuse of Office by PublicAbubakar UmarNo ratings yet

- US Vs Ah Chong, L-5272, March 19, 1910, 15 Phil. 488 (1910)Document7 pagesUS Vs Ah Chong, L-5272, March 19, 1910, 15 Phil. 488 (1910)Maria50% (2)

- Falls Among Older AdultsDocument59 pagesFalls Among Older AdultsShahrul Hafiz100% (1)

- Revision Notes Criminal LawDocument7 pagesRevision Notes Criminal Lawwatever100% (1)

- + Rhodes - A Systematic Approach To Clinical Moral Reasoning (Clinical Ethics 2007)Document6 pages+ Rhodes - A Systematic Approach To Clinical Moral Reasoning (Clinical Ethics 2007)Mercea AlexNo ratings yet

- Falls in Older PeopleDocument18 pagesFalls in Older PeoplePabloIgLopezNo ratings yet

- Japan's Government Social Policy On Management of Aging SocietyDocument7 pagesJapan's Government Social Policy On Management of Aging SocietyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- EBMDocument636 pagesEBMDaniel SalaNo ratings yet

- LeprosyDocument16 pagesLeprosyPriscilla Sund Nguyen100% (2)

- Advanced Practice in Nursing and the Allied Health ProfessionsFrom EverandAdvanced Practice in Nursing and the Allied Health ProfessionsPaula McGeeNo ratings yet

- Platon Notes - Obligations & Contracts (Gonzales)Document98 pagesPlaton Notes - Obligations & Contracts (Gonzales)Gracee Ramat0% (1)

- Multidisciplinary Team and Pharmacists Role in That TeamDocument5 pagesMultidisciplinary Team and Pharmacists Role in That TeamTimothy OgomaNo ratings yet

- Pros Sagssago Notes in Criminal Law 2017 EditionDocument316 pagesPros Sagssago Notes in Criminal Law 2017 EditionLEIGH100% (1)

- Health Systems Strengthening - The University of MelbourneDocument14 pagesHealth Systems Strengthening - The University of MelbourneEstefanía MariñoNo ratings yet

- (Full) Concept of Quasi-Delict ElementsDocument77 pages(Full) Concept of Quasi-Delict ElementsSasha BrausNo ratings yet

- Reflective Writing b8ll100Document22 pagesReflective Writing b8ll100Nurin HadNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez V Ponferrada DigestDocument1 pageRodriguez V Ponferrada DigestDrew Dalapu100% (1)

- Change InitiativeDocument7 pagesChange InitiativeWajiha ShaikhNo ratings yet

- 1 SyringomyeliaDocument26 pages1 SyringomyeliaYosafat Ate100% (1)

- Professional Accountability in NursingDocument4 pagesProfessional Accountability in NursingJohn N MwangiNo ratings yet

- Creating the Health Care Team of the Future: The Toronto Model for Interprofessional Education and PracticeFrom EverandCreating the Health Care Team of the Future: The Toronto Model for Interprofessional Education and PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Palliative CareDocument18 pagesEthical Issues in Palliative CareDinesh DNo ratings yet

- Alcoholic NeuropathyDocument4 pagesAlcoholic Neuropathyhis.thunder122100% (1)

- Module Guide For Palliative Care AssessmentDocument83 pagesModule Guide For Palliative Care AssessmentAnd ReiNo ratings yet

- Spirituality in Healthcare: Perspectives for Innovative PracticeFrom EverandSpirituality in Healthcare: Perspectives for Innovative PracticeNo ratings yet

- Dialysis Without Fear PDFDocument273 pagesDialysis Without Fear PDFandrada14No ratings yet

- The WHO Health Promotion Glossary PDFDocument17 pagesThe WHO Health Promotion Glossary PDFfirda FibrilaNo ratings yet

- The Child With Spina Bifida PDFDocument365 pagesThe Child With Spina Bifida PDFAna H.No ratings yet

- Ppta Standards of PracticeDocument3 pagesPpta Standards of PracticeChaddyBabeNo ratings yet

- Tools Iowa Ebnp-1 PDFDocument10 pagesTools Iowa Ebnp-1 PDFNovita Surya100% (1)

- Thesis (Noridja's Group)Document31 pagesThesis (Noridja's Group)DenMarkSolivenMacniNo ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument9 pagesOrgan DonationAravindan Sundar100% (1)

- 3806NRS Nursing Assignment HelpDocument5 pages3806NRS Nursing Assignment HelpMarry WillsonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Nursing Research Part 1Document22 pagesIntroduction To Nursing Research Part 1Ciedelle Honey Lou DimaligNo ratings yet

- Psychological ChangesDocument36 pagesPsychological ChangesAndrei La MadridNo ratings yet

- 3melnyk Ebp Asking Clinical QuestionDocument4 pages3melnyk Ebp Asking Clinical Questionapi-272725467No ratings yet

- Providing Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesProviding Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewLynette Pearce100% (1)

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) Studies Conducted Amongst Medical Students of IndiaDocument6 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) Studies Conducted Amongst Medical Students of IndiaAnonymous x8fY69CrnNo ratings yet

- Department of Health Departmental Report 2008Document253 pagesDepartment of Health Departmental Report 2008Bren-RNo ratings yet

- Oedojo Soedirham) : Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral SciencesDocument59 pagesOedojo Soedirham) : Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral SciencesAshri Nur IstiqomahNo ratings yet

- Original EssayDocument3 pagesOriginal EssayAj AquinoNo ratings yet

- Islam and Palliative CareDocument16 pagesIslam and Palliative CareShirakawa AlmiraNo ratings yet

- Time To Learn. Understanding Patient Centered CareDocument7 pagesTime To Learn. Understanding Patient Centered CareAden DhenNo ratings yet

- 20191212002111week 2 Assignment Nursing ResearchDocument2 pages20191212002111week 2 Assignment Nursing ResearchkelvinNo ratings yet

- Postop Physical Therapy in Orthopedic PatientsDocument1 pagePostop Physical Therapy in Orthopedic PatientsnvvharikrishnaNo ratings yet

- Recognising and Defining Clinical Nurse LeadersDocument4 pagesRecognising and Defining Clinical Nurse LeadersSholihatul AmaliyaNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation Grand Rounds NURS 441 - Clinical Management of Recovery Purpose of AssignmentDocument3 pagesRehabilitation Grand Rounds NURS 441 - Clinical Management of Recovery Purpose of Assignmentapi-348670719No ratings yet

- Newborn AssessmentDocument4 pagesNewborn Assessmentapi-400252098No ratings yet

- Unit 29 Health PromotionDocument4 pagesUnit 29 Health Promotionchandni0810100% (1)

- Evidence Based PracticesDocument5 pagesEvidence Based Practicesapi-527787868No ratings yet

- Impact of Fall Prevention Program Upon Elderly Behavior Related Knowledge at Governmental Elderly Care Homes in Baghdad CityDocument7 pagesImpact of Fall Prevention Program Upon Elderly Behavior Related Knowledge at Governmental Elderly Care Homes in Baghdad CityIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Ebp Formative Synthesis PaperDocument9 pagesEbp Formative Synthesis Paperapi-404415990No ratings yet

- Refining A Self-Assessment of Informatics Competency Scale Using Mokken Scaling AnalysisDocument9 pagesRefining A Self-Assessment of Informatics Competency Scale Using Mokken Scaling AnalysisTenIs ForMeNo ratings yet

- Nursing PhilosDocument8 pagesNursing Philosapi-527531404No ratings yet

- Piel Et Al - Understanding The Global Dimensions of Health (2005)Document303 pagesPiel Et Al - Understanding The Global Dimensions of Health (2005)Jaime Fernández-Aguirrebengoa100% (1)

- Stroke Canadian2010Document247 pagesStroke Canadian2010Dewi LuhNo ratings yet

- ACC1162 OEP To Prevent Falls in Older Adults - Jul07Document72 pagesACC1162 OEP To Prevent Falls in Older Adults - Jul07moliceiraNo ratings yet

- Use of Sedation in Palliative CareDocument13 pagesUse of Sedation in Palliative Careuriel_rojas_41No ratings yet

- Simulation & Gaming at NIDocument3 pagesSimulation & Gaming at NIFrancis ObmergaNo ratings yet

- MPU3313 MPU2313 Topic 6Document26 pagesMPU3313 MPU2313 Topic 6CheAzahariCheAhmad100% (1)

- PL - Platinum 01 - 07 - 2021Document52 pagesPL - Platinum 01 - 07 - 2021Nugraha Dwi Ananta RNNo ratings yet

- HP 2000 Inventec 6050A2498701-MB-A02 AMD PDFDocument45 pagesHP 2000 Inventec 6050A2498701-MB-A02 AMD PDFyenny naveaNo ratings yet

- Lenovo NM-A471 PDFDocument59 pagesLenovo NM-A471 PDFRat Noe0% (1)

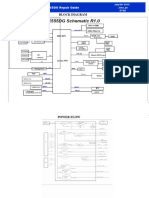

- Block Diagram: X555DG Repair GuideDocument5 pagesBlock Diagram: X555DG Repair GuideNugraha Dwi Ananta RN100% (1)

- Compal Confidential: P1VE6 LA7071P Schematics DocumentDocument37 pagesCompal Confidential: P1VE6 LA7071P Schematics DocumentChristiam OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Biostar H81MDV3 SpecDocument8 pagesBiostar H81MDV3 SpecNugraha Dwi Ananta RNNo ratings yet

- Rock S A0001118475 1Document49 pagesRock S A0001118475 1abg tuaNo ratings yet

- Sony MBX-208 - Quanta SY2 - MB - 0409cDocument36 pagesSony MBX-208 - Quanta SY2 - MB - 0409cNugraha Dwi Ananta RNNo ratings yet

- Toms River Regional School District Athletic Waiver and Release of Liability Form Related To COVID-19Document4 pagesToms River Regional School District Athletic Waiver and Release of Liability Form Related To COVID-19Asbury Park PressNo ratings yet

- Dela Llano Vs BiongDocument6 pagesDela Llano Vs BiongWhatever123456789No ratings yet

- Barredo v. GarciaDocument2 pagesBarredo v. GarciaGela Bea BarriosNo ratings yet

- PTE Academic Online Test Taker Handbook - May 2022Document28 pagesPTE Academic Online Test Taker Handbook - May 2022Tommy Linny H.No ratings yet

- TortsDocument2 pagesTortsGalanza FaiNo ratings yet

- Casupanan Vs LaroyaDocument8 pagesCasupanan Vs LaroyaKristine KristineeeNo ratings yet

- CLJ 3 Week 5-10Document13 pagesCLJ 3 Week 5-10Gierlie Viel MogolNo ratings yet

- United States v. Leslie Roberts, 978 F.2d 17, 1st Cir. (1992)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Leslie Roberts, 978 F.2d 17, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Crim Fact ScenarioDocument2 pagesCrim Fact ScenarioGouri DasNo ratings yet

- Draft IRR RA 10606 - Natl Health Ins Act 2013Document103 pagesDraft IRR RA 10606 - Natl Health Ins Act 2013roy rubaNo ratings yet

- 021 Samson v. Restrivera PDFDocument3 pages021 Samson v. Restrivera PDFDan Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Package Description: Manila Ocean Park Attractions PassDocument8 pagesPackage Description: Manila Ocean Park Attractions PassRenato OrosaNo ratings yet

- LEGMED CaseDocument16 pagesLEGMED CaseGabriel Jhick SaliwanNo ratings yet

- Far East Bank vs. CADocument5 pagesFar East Bank vs. CAMan HernandoNo ratings yet

- TORT Midterm ExamDocument6 pagesTORT Midterm ExamJenieNo ratings yet

- Cinco Vs CanonoyDocument5 pagesCinco Vs CanonoyChristine ErnoNo ratings yet

- Medical NegligenceDocument29 pagesMedical NegligenceVishwajeet GandhiNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Law of Torts - Author - Lakshmi SomanathanDocument5 pagesNature and Scope of Law of Torts - Author - Lakshmi SomanathanJasmine Singh100% (1)

- GEAC Self Declaration FormDocument3 pagesGEAC Self Declaration FormJenny CroweNo ratings yet

- 20ba086 GPCL PROJECT 2022Document16 pages20ba086 GPCL PROJECT 2022sayed abdul jamayNo ratings yet

- Filamer Vs Iac (LABOR LAW)Document5 pagesFilamer Vs Iac (LABOR LAW)Athena Venice MercadoNo ratings yet

- Draft Articles On The Responsibility of International Organizations (2011)Document16 pagesDraft Articles On The Responsibility of International Organizations (2011)ebrtzNo ratings yet