Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antimicrobial Activity of The Essential Oil of Phlomis Bracteosa

Uploaded by

Eduardo De Souza MafraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antimicrobial Activity of The Essential Oil of Phlomis Bracteosa

Uploaded by

Eduardo De Souza MafraCopyright:

Available Formats

ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF THE ESSENTIAL OIL OF PHLOMIS BRACTEOSA

R. K. Joshi*, Veena Pande**, B. C. Thakuri*** *Regional Medical Research Centre, Indian Council of Medical Research, Belgaum, Karnataka-590 010, India. **Department of Biotechnology, Kumaun University Nainital, Uttarakhand-263002, India. ***Siddhanath Science Campus, Mahendranagar, Kanchanpur, Nepal.

Abstract: The essential oil was isolated from the aerial parts of Phlomis bracteosa Royle ex Benth., a hairy erect herb. The leaves and flowers of this species are used as carminative, stimulant and locally known as Ballikotu, Calba, Salba in Turkish traditional medicine. The antimicrobial activity of Phlomis bracteosa was studied using well diffusion method. The activity was tested against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi at different concentrations (0.25 g/ml, 0.125 g/ml and 0.062 g/ml) of the essential oil. Keywords: Phlomis bracteosa; Lamiaceae; Antimicrobial activity.

INTRODUCTION Essential oils are known to possess antimicrobial activity, which has been evaluated mainly in liquid medium. Several essential oils and their isolates have been found to exhibit strong antibacterial and antifungal activity. The essential oil are supposed to interfere with intermediary metabolism of microorganisms by changing the rate of an enzyme reaction influencing nutrient uptake from the medium affecting enzyme synthesis at nuclear or ribosomal level or changing membrane structures. Phlomis bracteosa Royle ex Benth. of the family Lamiaceae is an erect hairy plant 20-80 cm, with heart-shaped toothed leaves, and pink-purple flowers crowded into a few large whorls and forming an interrupted spike. The whorls are 2.5-4 cm across, corolla 1.5-2 cm, the tube shorter than the calyx, upper lip larger hooded, very hairy and with a fringe of white hairs, the lower lip smaller, 3-lobed, calyx hairy, with five narrow awl-shaped teeth, much shorter than the calyx tube. The bracts linearlanceolate, bristly-haired, without a spiny tip. The leaves are 5-10 cm, stalked, hairy. The plant is distributed in temperate region from Kashmir to Kumaun and Afghanistan to South West China from an elevation of 1200-4000 m1,2. Phlomis species are recorded as herbal drugs being used ethno pharmacologically, tonic and as stimulant3. The leaves and flowers of Phlomis species are used as carminative, stimulant and locally known as Ballikotu, Calba, Salba in Turkish traditional medicine 4,5. Several essential oil constituents of the Phlomis species have been reported from

different parts of the world6-16. The major constituent of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa was reported as germacrene D (34.3%). Other minor constituents were sabinene (6.2%), germacrene D-4-ol (4.9%), linalool (4.8%) and -bulnesene (3.5%)17. The essential oils of Phlomis lanata, Phlomis fruticosa, Phlomis cretica, Phlomis samia, Phlomis ferruginea and the ethanol extract of Phlomis fruticosa showed antimicrobial activities15, 18-20, while the essential oil of Phlomis linearis has also been reported anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory activity 21. The iridoids, like lamiide isolated from the dichloromethane and methanol extracts of Phlomis crinita showed the topical anti-inflammatory activity 22 . The compounds, luteolin 7-O--D-glucopyranoside and chrysoeriol 7-O--D-glucopyranoside were isolated from Phlomis brunneogaleata and have anti-malarial property23. Phlomis grandiflora used in folk remedy as gastroprotective crude drug and possess antiulcerogenic activity24. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report on the antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa. MATERIALS AND METHODS Plant Material The aerial parts of Phlomis bracteosa were collected before flowering phase from the Pindari glacier area, district Bageswer of North-West Himalaya of Uttarakhand, India, at a height of 3200 m. The plant was identified by Prof. Y. P. S. Pangtey, Botany Department, Kumaun University, Nainital. The

Author for Correspondence: R. K. Joshi, Regional Medical Research Centre, Indian Council of Medical Research, Belgaum, Karnataka-590 010, India. Email: joshirk_natprod@yahoo.com

63

Scientific World, Vol. 9, No. 9, July 2011

voucher specimen (No. 3318) was confirmed and deposited in the herbarium of the Botany Department, Forest Research Institute, Dehradun. Isolation of Essential Oil The aerial parts (1 kg) of Phlomis bracteosa were steam distilled for 3 hours using a copper still fitted with spiral glass condensers for 3 hours and extracted with n-hexane and dichloromethane. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and the solvent was recovered using a thin film rotary vacuum evaporator at 25o-30oC. The oil yield was 0.02% (v/w). Antimicrobial Assay Media Preparation Bacterial Media Nutrient agar (NA) was used for the screening of antibacterial activity of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. NA was weighed as per instructions provided by the manufacturer and dissolved in distilled water. After proper plugging, it was autoclaved at 120oC and 15 lbs for 20 minutes. Autoclaved nutrient agar when cooled at 45oC was poured into sterilized petri dishes containing nearly 20 ml agar medium under aseptic condition and kept undisturbed as such till solidify. After solidification, these petri plates were incubated at 37oC1oC overnight for sterility testing. Fungal Media Preparations of potato dextrose agar (PDA), sabourauds agar (SA) and yeast extract potato dextrose agar (YEPDA) media were used as per instruction provided by the manufacturer, for different fungal strains viz., Micrococus canis, trichophyton rubrum and Candida albicans, respectively. After proper plugging, the media were autoclaved at 120oC and 15 lbs for 20 minutes. Autoclaved PDA, SA and YEPD media when cooled at 45oC was poured into sterilized petri plates containing nearly 20 ml growth media under aseptic condition till solidified. After solidification these petri plates were incubated for sterility testing. The PDA plates incubated at 25oC 1oC while SA and YEPD plates at 30oC 1oC for ten days, seven days and 48 hours, respectively.

Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oil The essential oil of 0.25 g/ml, 0.125 g/ml and 0.062 g/ml were prepared with some modification in 50% ethanol25-27 and tested against human pathogens Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and Proteus vulgaris ((Gram-negative) bacteria. It was demonstrated by well diffusion method. Antifungal Activity of the Essential Oil The essential oil of 0.25g/ml, 0.12g/ml and 0.062g/ml were prepared with some modification in 50% ethanol25-27 and tested against Microsporum canis, Trichophyton rubrum and Candida albicans fungi. It was demonstrated by well diffusion method. Well Diffusion Method Antibacterial and antifungal activities of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa were tested using well diffusion method28. The autoclaved media was poured in the sterilized petri plates. These plates were dried for a period of 20 minutes under aseptic condition before its use. Freshly grown cultures of the tested bacteria and fungi in their media were streaked over the plates using a platinum wire inoculation loop. On sterile media plates, well of 6.0 mm diameter were punched with the help of a sterile gel cutter. Wells were sealed with the molten media to prevent the escape of essential oil through bottom. In the well of separate Petri plates 15 l of different concentrations (0.25g/ml, 0.125g/ml and 0.062g/ml) of essential oil were delivered. The positive control were used gentamicin 1% (w/v) (Fulford (India) Limited, Hyderabad) and fluconazole 1% (w/v) (Lark Laboratories (India) Ltd., New Delhi) for antibacterial and antifungal activity, respectively. The plates were incubated at 37oC 1oC for 24 hours for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and 25oC 1oC, 30oC 1oC and 30oC 1oC for Microsporum canis, Trichophyton rubrum and Candida albicans fungi for ten days, seven days and 48 hours respectively. The plates were observed for the zone clearance around the wells. The zones of inhibition were calculated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zone around the well in millimeter including the well diameter. The readings were taken in three different replicates and the average values were tabulated (Table 1).

Table 1: Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa Royle ex Benth.

Dilution of essential oil in 50 % ethanol, V/V: applied dose: 15 l Standard: applied dose: 15 l Diameter of well = 6 mm NA= No activity

a b

Scientific World, Vol. 9, No. 9, July 2011

64

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The present study was designed to evaluate the qualitative antimicrobial activity of the aerial parts of Phlomis bracteosa essential oil. The essential oil from this plant exhibited antimicrobial activity. The activity may be attributed to the presence of germacrene D, sabinene, -bulnesene, germacrene D-4-ol, linalool, eugenol and isoeugenol or other miner constituents17 were present in Phlomis bracteosa essential oil. The chemical components exert their toxic effects against the microorganisms through the disruption of bacteria or fungal membrane integrity29-31. The antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa showed significant activity against the tested microorganisms at three different concentrations (0.25 g/ml, 0.125 g/ml and 0.062 g/ml). The results of antimicrobial activity of the essential oil using well diffusion assay are summarized in Table 1. The oil showed significant activity against tested Gram-positive and Gramnegative bacteria and Trichophyton rubrum was much susceptible to the essential oil, followed by Microsporum canis and Candida albicans are relatively less susceptible. The principal component of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa was germacrene D. The literature revealed that the germacrene D rich essential showed good antimicrobial and cytotoxicity activity. In vitro cytotoxicity activity of germacrand D was found cytotoxic against Human Hs 578T breast ductal carcinoma cells32. According to previous reports eugenol displayed potent activity against Candida albicans biofilms in vitro with low cytotoxicity and therefore has potential therapeutic implication for biofilm-associated candidal infections 33. Another study also revealed the presence of eugenol in the essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum showed good antimicrobial activity34. CONCLUSION

10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17.

Sarkhail, P., Amin, G. and Shafiee, A. 2006. DARU. 14(2): 71-74. Masoudi, S., Rustaiyan, A., Azar, P. A. and Larijani, K. 2006. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 18: 16-18. Basta, A., Tzakou, O. and Couladis, M. 2006. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 21(5): 795-797. Kirimer, N., Baser K. H. C. and Kurkcuoglu, M. 2006. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 18: 600-601. Semnani K. M., Moshiri, K. and Akbarzadeh, M. 2006. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 18: 672-673. Formisano, C., Senatore, F., Bruno, M. and Bellone, G. 2006. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 21(5): 848-851. Tajbakhsh, M., Rineh, A. and Khalilzadeh, M. A. 2007. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 19: 501-503. Joshi R. K. 2007. Terpenoid Composition and Biological Activity Determination of some Labiatae and Compositae Species, Ph.D. Thesis, Kumaun University. Nainital, India. Couladis, M., Tanimanidis, A., Tzakou, O., Chinou, I. B. and Harvala, C. 2000. Planta Medica, 66(7): 670-672. Ristic, M. D., Duletic-Lausevic, S., Knezevic-Vukcevic, J., Marin, P. D., Simic, D., Vukojevic, J., Janackovic, P. and Vajs, V. 2000. Phytotherapy Research, 14(4): 267-271. Aligiannis, N., Kalpoutzakis, E., Kyriakopoulou, I., Mitaku, S. and Chinou, I. B. 2004. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 19(4): 320-324. Demirci, B., Dadandi, M. Y., Paper, D. H., Franz, G. and Baser, K. H. C. 2003. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung. 58c: 826-829. Giner, R. M., Sanz, M. J., Ferrandiz, M. L., Recio, M. C., Terencio, M. C. and Rios, J. L. 1991. Planta Medica, 57 (Supplement 2) A53. Kirmizibekmez, H., Calis, I., Perozzo, R., Brun, R., Donmez, A. A., Linden, A., Ruedi, P. and Tasdemir, D. 2004. Planta Medica, 70(8): 711-717. Gurbuz, I., Ustun, O., Yesilada, E., Sezik, E. and Kutsal, O. 2003. Journal of Ethanopharmocology, 88(1): 93-97. Sivropoulou, A., Papanikolaou, E., Nikolaou, C., Kokkini, S., Lanaras, T. and Arsenakis, M. 1996. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 44(5): 1202-1205. Adam, K., Sivropoulou, A., Kokkini, S., Lanaras, T. and Arsenakis, M. 1998. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 46(5): 1739-1745. Maksimovic, Z. A., Dordevic, S. and Mraovic, M. 2005. Fitoterapia. 76(1): 112-114. Cruickshank, R., Duguid, J. P., Marmion, B. P. and Swain, R. H. 1975. Medical Microbiology. 12th ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingston. Andrews, R. E., Parks, L. W. and Spence, K. D. 1980. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 40(2): 301-304. Uribe, S., Ramirez, T. and Pena, A. 1985. The Journal of Bacteriology. 161(3): 195-200. Knoblock, K., Pauli, A., Iberl, B., Weis, N. and Weigand, H. 1988. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 1: 119-128. Palazzo1, M. C., Wright, H. L., Agius, B. R., Wright, B. S., Moriarity, D. M., Haber, W. A. and Setzer, W. N. 2009. Chemical compositions and biological activities of leaf essential oils of six species of Annonaceae from Monteverde, Costa Rica, Records of Natural Products. 3(3): 153-160. Miao H., Minquan, D., Mingwen, F. and Zhuan, B. 2007. Mycopathologia. 63(3): 137-143. Faria, T. J., Ferreira, R. S., Yassumoto, L., Souza, J. R. P., Ishikawa, N. K. and Barbosa, A. M. 2006. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 49(6): 867-871.

18. 19.

20.

21. 22. 23.

24. 25.

26.

In vitro antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Phlomis bracteosa showed significant activity against tested human pathogens. Thus the oil of Phlomis bracteosa could be a source of germacrene D a good cytotoxic and antimicrobial constituent. REFERENCES

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Gupta, R. K. 1968. Flora Nainitalensis. Navayug Traders, New Delhi. Polunin, O. and Stainton, A. 1984. Flowers of the Himalaya. Oxford University Press, New Delhi. Gennadios, P. G. 1997. Phytological Dictionary. Trohalia ed., Athens. Baytop, T. 1984. Therapy with Medicinal Plants (Past and Present), Istanbul University publication, Istanbul, Turkey. Baytop, T. 1997. Dictionary of Turkish Plant Names. TDK Yay., Ankara, Turkey. Semnani K. M. and Saeedi M. 2005. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 20(3): 344-346. Demirci, B., Baser, K. H. C. and Dadandi, M. Y. 2006. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 18: 328-331. Sarkhail, P., Amin, G. and Shafiee, A. 2004. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 19: 538-540. Ghassemi, N., Sajjadi S. E. and Lame, M. A. 2001. DARU. 9(1-2): 48-50.

27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32.

33. 34.

65

Scientific World, Vol. 9, No. 9, July 2011

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- MENTAL HEALTH NURSING ExamDocument5 pagesMENTAL HEALTH NURSING ExamSurkhali BipanaNo ratings yet

- The Art and Practice of Diagnosis in Chinese Medicine. NIGEL CHINGDocument794 pagesThe Art and Practice of Diagnosis in Chinese Medicine. NIGEL CHINGИгорь Клепнев100% (13)

- Epiglottitis: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Explanatio N Planning Nursing Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument3 pagesEpiglottitis: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Explanatio N Planning Nursing Intervention Rationale EvaluationfifiNo ratings yet

- HRMDocument20 pagesHRMSyeda AleenaNo ratings yet

- Tumor AngiogenesisDocument35 pagesTumor AngiogenesisDoni Mirza KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Anemia in PregnancyDocument5 pagesAnemia in PregnancySandra GabasNo ratings yet

- Coca Cola Fairlife CaseDocument4 pagesCoca Cola Fairlife Caseapi-315994561No ratings yet

- Introduction To Different Resources of Bioinformatics and Application PDFDocument55 pagesIntroduction To Different Resources of Bioinformatics and Application PDFSir RutherfordNo ratings yet

- Short Essay On ObesityDocument6 pagesShort Essay On ObesityLisa Wong100% (1)

- Immunotherapy A Potential Adjunctive Treatment For Candida - Il e IfnDocument6 pagesImmunotherapy A Potential Adjunctive Treatment For Candida - Il e IfnLuiz JmnNo ratings yet

- Doh2011 2013isspDocument191 pagesDoh2011 2013isspJay Pee CruzNo ratings yet

- M. Pharm. Pharmaceutics 2011 SyllabusDocument19 pagesM. Pharm. Pharmaceutics 2011 SyllabusRammani PrasadNo ratings yet

- The Barrier To Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice Among Novice TherapistsDocument11 pagesThe Barrier To Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice Among Novice TherapistsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Export of SpicesDocument57 pagesExport of SpicesJunaid MultaniNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Biology Investigatory Project 561e79b91f5a0Document17 pagesDokumen - Tips Biology Investigatory Project 561e79b91f5a0Upendra LalNo ratings yet

- BNMHGDocument34 pagesBNMHGAnonymous lt2LFZHNo ratings yet

- Rockwool Slab Data Sheet - (ProRox Formerly RW Slab)Document7 pagesRockwool Slab Data Sheet - (ProRox Formerly RW Slab)stuart3962No ratings yet

- Forensic MedicineDocument157 pagesForensic MedicineKNo ratings yet

- Module 11 Rational Cloze Drilling ExercisesDocument9 pagesModule 11 Rational Cloze Drilling Exercisesperagas0% (1)

- Career 1Document2 pagesCareer 1api-387334532No ratings yet

- Recist Criteria - Respon Solid Tumor Pada TerapiDocument18 pagesRecist Criteria - Respon Solid Tumor Pada TerapiBhayu Dharma SuryanaNo ratings yet

- Clinic by Alissa QuartDocument4 pagesClinic by Alissa QuartOnPointRadioNo ratings yet

- 1PE 4 Q3 Answer Sheet March 2024Document3 pages1PE 4 Q3 Answer Sheet March 2024Chid CabanesasNo ratings yet

- Feeding Norms Poultry76Document14 pagesFeeding Norms Poultry76Ramesh BeniwalNo ratings yet

- BUPA Medical Service Providers Lebanon Updated-April 2013Document3 pagesBUPA Medical Service Providers Lebanon Updated-April 2013gchaoul87No ratings yet

- CV - Mahbub MishuDocument3 pagesCV - Mahbub MishuMahbub Chowdhury MishuNo ratings yet

- What Is FOCUS CHARTINGDocument38 pagesWhat Is FOCUS CHARTINGSwen Digdigan-Ege100% (2)

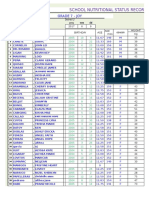

- School Nutritional Status Record: Grade 7 - JoyDocument4 pagesSchool Nutritional Status Record: Grade 7 - JoySidNo ratings yet

- Ufgs 01 57 19.01 20Document63 pagesUfgs 01 57 19.01 20jackcan501No ratings yet

- My Evaluation in LnuDocument4 pagesMy Evaluation in LnuReyjan ApolonioNo ratings yet