Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Burning Mouth Syndrome

Uploaded by

Fathah MuhammadOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Burning Mouth Syndrome

Uploaded by

Fathah MuhammadCopyright:

Available Formats

34 Burning Mouth Syndrome

Miriam Grushka, DDS, PhD, Joel B. Epstein, DMD, MSD, FRCD(C), and Jill S. Kawalec, PhD

Suggested etiologies, 355 Evolving concept of etiology, 355 Management, 356

Workup and hypothetic model, 357 Summary and conclusions, 357 Suggested reading, 357

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is currently defined as a condition in which burning pain in the tongue or other oral mucous membranes occurs in association with normal signs and normal laboratory findings. Although there is no clear understanding of pathogenesis of BMS, recent concepts are dramatically affecting the manner in which clinicians conceptualize this disorder and the way in which these patients are managed. In BMS, pain intensity and other symptoms commonly develop gradually over time, although in some patients, onset is sudden and precipitous. The most common sites of burning are the anterior tongue, anterior hard palate, and lower lip, but the distribution of oral sites affected does not appear to affect the natural history of the disorder or the response to treatment. Burning mouth syndrome may persist for many years. Although the majority of patients cannot identify an apparent cause of onset, approximately one-third of patients attribute the onset of their symptoms to a previous dental procedure, illness, or a course of antibiotics. Thus, for some patients the possibility exists of neurologic change as an etiologic factor by virtue of viral infection, mechanical damage, or neurotoxic effect of local anesthetics. Nocturnal pain is not common for most patients with BMS, rather, the pain, usually of moderate to severe intensity, gradually increases throughout the day, reaching maximum intensity by late evening. As a result, it is not uncommon for patients with BMS to report having difficulty falling asleep at night and experiencing interrupted sleep. Reported mood changes, such as irritability and decreased desire to socialize, may be related to altered sleep patterns. Personality characteristics including depression and anxiety are commonly reported in patients with BMS

and may affect the pain report or be secondary to the chronic pain. The significance of the diurnal variation is unknown but may be related to postural changes in blood flow or to central nervous system (CNS) changes during sleep. There is some support for this concept in the literature, which has demonstrated decreased tongue temperature in BMS during the day; nighttime temperature has not been measured. Most clinical studies suggest that oral burning is frequently accompanied by dry mouth and thirst (despite lack of evidence of decreased salivary flow in most patients); altered taste (dysgeusia); and additional pain complaints, including facial pain and pain at other sites. Taste and pain are both mediated by small-diameter fibers, whereas salivary stimulation is under the control of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. Interestingly, whereas both oral burning and altered taste are decreased by stimulation with food, rinsing with a local anesthetic elixir usually increases the oral burning pain but decreases the dysgeusia. Although BMS may persist for many years following onset, partial remissions have been found to occur in approximately two-thirds of patients within 6 to 7 years after onset. No significant differences in age, gender, duration of disease, or distribution of burning sites have been found among individuals who experience partial or full remission compared with those whose burning continues. Recent studies, however, have suggested that responsiveness to treatment in BMS may be enhanced with shorter disease duration. It is not known what effect treatment has in the long-term on the disease process itself. Further, no studies have yet investigated whether earlier intervention or earlier and better pain control also lead to earlier disease remission.

354

BURNING MOUTH SYNDROME

355

Suggested etiologies

There is a widespread belief that BMS may be the result of specific systemic diseases or nutritional deficiencies, including B vitamins and iron. However, no consistent relation has been found to support this belief. Further, even when abnormal laboratory results are identified, management and correction of these findings usually do not lessen the oral burning and other associated complaints. The current definition of BMS excludes patients with clinical mucosal conditions. However, a higher incidence of oral soft-tissue lesions, such as gingivitis, periodontitis, ulcerative or erosive lesions, or geographic, fissured, scalloped, or erythematous tongue has been reported in patients with BMS, and the possibility that these conditions may cause irreversible neuropathic changes has not yet been fully explored. Similarly, the possibility that conditions such as Sjgren syndrome, other connective tissue diseases, and diabetes may cause neuropathic changes that result in oral burning also requires consideration. Burning pain, the main feature in BMS, is also a characteristic feature of some post-traumatic nerve injuries. In contrast to other post-traumatic nerve injuries, alterations in perception to touch, temperature, two-point discrimination, and threshold pain have been noted infrequently in BMS. On the other hand, abnormalities in taste and heat pain tolerance have been noted, and a recent report by Lauritano and colleagues has demonstrated subclinical polyneuropathy in 50% of patients with BMS, involving a loss of function in small-diameter nerve fibers. In this study, polyneuropathy was determined by means of quantitative sensory examination, tongue and face telethermography, and selected tongue biopsy. Qualitative and quantitative differences in some sensory functions of patients with BMS have also been noted, with argon laser stimulation. Other recent studies have identified loss of taste, especially to bitter, in the taste buds subserved by the chorda tympani nerve. Abnormalities in the blink reflex of patients with BMS, associated with disease duration, also suggest a possible generalized pathologic involvement of the nervous system, leading to modification in peripheral or CNS processing in BMS. Although there is strong evidence from clinical studies to suggest that BMS is most prevalent in postmenopausal women in their mid- to late fifties, some recent epidemiologic data suggest a more equal male to female ratio. If menopause does appear to play a role in BMS, its mechanism remains unclear, since most reports suggest that oral burning is not usually reversible with hormone replacement therapy.

It is also notable that in BMS most studies have not demonstrated a significant decrease in salivary flow rate despite subjective complaints of mouth dryness and thirst. In contrast, significant alterations in salivary pH, buffering capacity, proteins, mucin, and immunoglobulins have been documented. Changes in salivary constituents rather than overall reduction in flow rate appear to be of significance in BMS and suggest involvement of sympathetic or parasympathetic function in BMS in addition to neuropathic injury. The mechanism whereby the autonomic nervous system is involved in BMS has also gone largely unexplored. Although current evidence clearly indicates a strong psychological component within BMS, there still exists no evidence of a close causal relation between psychogenic factors and burning mouth. Personality characteristics, such as depression and anxiety, which are common to BMS, may be secondary to the pain in accord with the types of personality changes noted in other chronic pain conditions. Most studies have also not supported chemical irritation or allergic reaction to dental materials as a significant cause of BMS; similarly, there has been little support for galvanic currents as a causative factor. However, mechanical irritation caused by dentures may be a factor in some patients, since errors in denture design and parafunctional habits with associated myofascial pain have been reported in BMS. Whether the parafunction is secondary to pain or is part of the disorder is unknown. Interestingly, there have recently been case reports of oral burning secondary to the use of angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, such as captopril, enalapril, and lisinopril, which has remitted following discontinuation of the medication. Loss of taste sensation has also been reported to occur with use of ACE inhibitors, suggesting an additional link between pain and taste.

Evolving concept of etiology

Continuing research suggests that BMS may represent a peripheral or centrally mediated neuropathic condition with multiple etiologies. In view of the increase in oral burning after a topical anesthetic rinse, it has been suggested that oral burning may be a centrally based neuropathic condition that results in decreased peripheral inhibition of the trigeminal nerve. This is in accord with taste studies that have shown that loss of inhibition between the central projection areas of the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal taste nerves following peripheral injury to either nerve can result in the production of phantom tastes. Preliminary spatial taste

356

CHAPTER 34

testing in patients with BMS has provided further support for the possibility that for some patients, oral burning may result from the loss of inhibition of nociceptive trigeminal fibers secondary to injury to either the chorda tympani or the glossopharyngeal nerves. Recent studies have demonstrated a relation between pain, taste, and alterations in the perception of oral dryness. For instance, there have been reports that taste loss, burning pain of the tongue and lips, tingling, and drooling can follow mild nerve injury after local anesthetic block (without extraction) to the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves. Similarly, paresthesias, pain, abnormal tastes, and drooling have been reported to follow damage to the inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve during mandibular third molar extraction. Moreover, although a male:female ratio of 30:70 in patients who have suffered injury to the trigeminal nerve during lower third molar extraction has been demonstrated, women and older patients tended to have the most severe complaints.

Management

For many years BMS has been managed with low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) based on earlier reports of their effectiveness as analgesics in alleviating oral burning in some patients with BMS. Many tricyclics have been used, including amitriptyline, desipramine, nortriptyline, imipramine, and clomipramine, although only amitriptyline has been evaluated in controlled clinical trials. In contrast, controlled trials of trazodone, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), have failed to document relief of BMS. There are no data that indicate that other SSRIs are effective in BMS. Recently, several studies have suggested that various benzodiazepines, including clonazepam, a GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) receptor agonist, may be effective for various orofacial pain disorders, including BMS. Clonazepam is thought to have both peripheral and central effects and to bind more to central than to peripheral GABA receptor sites than other benzo-

Burning mouth dryness

Local anesthetic rinse Pain decreases Look for local factors Local factors treat Pain increases Consider deafferentation or neuropathic pain Sjgren syndrome

-Local factors O

Salivary flow studies resting/stimulated

If requires workup for Sjgren syndrome

Sjgren

If flow is normal

Treat salivary flow

Spatial taste testing

If pain persists

Normal

Abnormal

Look for local factors, other systemic causes, GERD, B12, denture problems

Consider BMS or Sjgren with neuropathic damage if salivary flow decreased

Treat burning

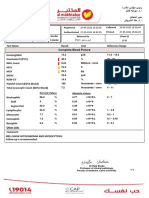

Figure 341 disease.

Proposed workup for the diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome. GERD = gastroesophageal reflex

BURNING MOUTH SYNDROME

357

diazepines. Notably, the study by Grushka and colleagues showed that clonazepam was effective in relieving taste dysgeusias and oral dryness along with the oral burning. Other medications and treatments recommended for the symptomatic relief of the burning pain include topical capsaicin; the monoamine oxidase inhibitor tranylcypromine sulphate in combination with diazepam, and the systemic anesthetic mexiletine, a use-dependent sodium channel blocker, all of which have been used for other neuropathic pain conditions. However, there are no controlled studies validating the effectiveness of any of these medications.

A. Injury to cranial nerve V Inflammation geographic or fissured tongue Vascular changes diabetes? Tissue changes Sjgren syndrome? Infection candida or herpes

B. No injury to cranial nerve V Viral infection Middle ear infection Loss of taste buds secondary to menopause

Damage to CN V

Peripheral nerve injury

Damage to VII and/or IX

Increased firing from V

Loss of inhibition of V

Workup and hypothetic model

A new approach to the diagnosis of BMS, based on the above review, is outlined in Figure 341. Based on the assumption that BMS is a neuropathic pain condition secondary to loss of inhibition of the trigeminal nociceptive fibers, this approach seeks objective evidence of oral dryness, taste disturbance, and effect of topical anesthetic. In contrast to earlier diagnostic paradigms, this diagnostic paradigm is one of inclusion and not exclusion. Hopefully, with this type of modeling, criteria for inclusion, much as for other diseases like Sjgren syndrome, will be developed. Figure 342 presents a hypothetic model of the multifactorial nature of BMS. This includes burning pain as the result of increased excitatory output of the trigeminal nerve either from direct injury to the nerve, leading to increased output, or from decreased inhibition of the trigeminal nerve, leading to increased spontaneous output. Treatment depends on the mechanism of injury and helps direct investigation. This is thought to be the first easily testable model of BMS.

Spontaneous firing of V

Pain

Behavioral changes

Stress Fatigue

A. Treatment Decrease sensory output through local anesthetic, anti-inflammatories, topical steroids, treat infections

B. Treatment Increase inhibition of V (eg, stimulation through taste) Decrease spontaneous firing through medication (tricyclics, benzodiazepines, other anticonvulsants)

Figure 342

Hypothetic model for burning mouth syndrome.

Suggested reading

Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Reed D, Williams A. Supertasting, earaches, and head injury: genetics and pathology alter our taste worlds. Neurosi Biobehav Rev 1996;20:7987. Bartoshuk LM, Grushka M, Duffy VB, et al. Burning mouth syndrome: A pain phantom in supertasters who suffer taste damage? (Abstr) Proceedings of the American Pain Society, November 1998, San Diego, California. Basker RM, Main DMG. The cause and management of burning mouth condition. Spec Care Dentist 1991;11:8996. Ben Aryeh H, Gottlieb I, Ish-Shalom S, et al. Oral complaints related to menopause. Maturitas 1996;24:1859. Formaker BK, Mott AE, Frank ME. The effects of topical anesthesia on oral burning in burning mouth syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998;885:776801. Grushka M, Epstein E, Mott A. An open-label, dose escalation pilot study of the effect of clonazepam in burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998;86:55761. Grushka M, Sessle BJ, Howley TP. Psychophysical assessment of tactile, pain, and thermal sensory functions in burning mouth syndrome. Pain 1987;28:16984.

Summary and conclusions

It is currently believed that morphologic alterations in peripheral tissue attributable to injury or disease can cause biochemical and pathophysiologic changes in nociceptive neurons in the CNS. As a result of these changes, ongoing neuronal activity, referral of pain, and response of nociceptive-specific neurons to previously non-noxious stimuli can occur. These types of conditions may occur in BMS as a result of common systemic or local disorders in which nerve damage occurs to either the trigeminal nerve directly or other cranial nerves, which usually inhibit oral nociceptive activity. Hopefully, with further testing, further elucidation of the model will occur and universally accepted criteria for the diagnosis of BMS will be established.

358

CHAPTER 34

Haas DA , Lennon D. A 21-year retrospective study of reports of paresthesia following local anesthetic administration. J Can Dent Assoc 1995;61:31930. Jaaskelainen SK, Forssell H, Tenovuo O. Abnormalities of the blink reflex in burning mouth syndrome. Pain 1997;73: 45560. Lehman CD, Bartoshuk LM, Catalanotto FC, et al. Effect of anesthesia of the chorda tympani nerve on taste perception in humans. Physiol Behav 1995;57:94351.

Ship J, Grushka M, Lipton JA, et al. Burning mouth syndrome: an update. J Am Dent Assoc 1995;126:84253. Woda A, Navez ML, Picard P, et al. A possible therapeutic solution for stomatodynia (burning mouth syndrome). J Orofac Pain 1998;12:2728. Zakrzewska MM, Jamlyn PJ. Facial pain. In: Crombie IK, ed. Epidemiology of pain. Seattle: IASP Press, 1999:175 82.

You might also like

- Semarang Semarang: Bp. Priyono, S.Kep. JeparaDocument2 pagesSemarang Semarang: Bp. Priyono, S.Kep. JeparaFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- ASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDocument11 pagesASIO4ALL v2 Instruction ManualDanny_Grafix_1728No ratings yet

- Serba Serbi Nikahan Dila FathahDocument8 pagesSerba Serbi Nikahan Dila FathahFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- SN VB2008 ProDocument1 pageSN VB2008 ProVian't NduablekNo ratings yet

- Imipenem - Penicilin - Efotaxim Plusss GentamicinDocument6 pagesImipenem - Penicilin - Efotaxim Plusss GentamicinFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- 389 FullDocument8 pages389 FullTaufik IndrawanNo ratings yet

- Febrile Seizures The Role of IntermittentDocument3 pagesFebrile Seizures The Role of IntermittentFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Uptodat Febrile SeizureDocument15 pagesUptodat Febrile SeizureFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Frozen ShoulderDocument14 pagesFrozen ShoulderFathah Muhammad100% (2)

- Study: Observational Travelers' DiarrheaDocument5 pagesStudy: Observational Travelers' DiarrheaFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Beta Lactam Plus Aminoglicoside SinergyDocument2 pagesBeta Lactam Plus Aminoglicoside SinergyFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Aminoglycoside Β-Lactam Vsβ-Lactam MonotherapyDocument10 pagesAminoglycoside Β-Lactam Vsβ-Lactam MonotherapyFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- P 87-89Document3 pagesP 87-89Theresa Lagmay100% (1)

- Guideline Who Preeclampsia-EclampsiaDocument48 pagesGuideline Who Preeclampsia-EclampsiaRahmania Noor AdibaNo ratings yet

- Indian Pediatrics - Febrile SeizureDocument8 pagesIndian Pediatrics - Febrile SeizureFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- PNM Thoraxan UpdateDocument5 pagesPNM Thoraxan UpdateFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Harrison's 17th EdDocument3 pagesHarrison's 17th EdShila Lupiyatama50% (2)

- 1537 Bedah PlastikDocument11 pages1537 Bedah PlastikFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Plantar Fasciitis 2004 RachelleDocument8 pagesPlantar Fasciitis 2004 RachelleFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Anatpro 1Document3 pagesAnatpro 1Fathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bone HealingDocument4 pagesJurnal Bone Healingsecret_sunsetNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2007 Varraso 488 95 PFDocument8 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2007 Varraso 488 95 PFFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- WertyDocument6 pagesWertyFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- ESC Guideline On Heart Failure PDFDocument55 pagesESC Guideline On Heart Failure PDFJuang ZebuaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Rachael Stanton Resume Rachael Stanton LVT 1 2Document2 pagesRachael Stanton Resume Rachael Stanton LVT 1 2api-686124613No ratings yet

- All India Hospital ListDocument303 pagesAll India Hospital ListwittyadityaNo ratings yet

- Management of The Third Stage of LaborDocument12 pagesManagement of The Third Stage of Laborayu_pieterNo ratings yet

- Pep Mock Exam Questions Updated - 2Document84 pagesPep Mock Exam Questions Updated - 2Cynthia ObiNo ratings yet

- Barium Swallow Meal Follow-Through MealDocument2 pagesBarium Swallow Meal Follow-Through MealPervez Ahmad AhmadNo ratings yet

- Vascular DementiaDocument8 pagesVascular Dementiaddelindaaa100% (1)

- CONJUNCTIVITIS or Pink Eye, Emotional and Spiritual MeaningDocument1 pageCONJUNCTIVITIS or Pink Eye, Emotional and Spiritual MeaningSarah g.No ratings yet

- Bromocriptine Tablet Product LeafletDocument6 pagesBromocriptine Tablet Product Leafletadam malikNo ratings yet

- Modern TimesDocument58 pagesModern TimesMicah DomingoNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice - AssignmentDocument20 pagesMedical Malpractice - Assignmentk123s100% (1)

- Rizal in Ateneo de Manila and USTDocument8 pagesRizal in Ateneo de Manila and USTDodoy Garry MitraNo ratings yet

- Borrelia RecurrentisDocument10 pagesBorrelia RecurrentisSamJavi65No ratings yet

- Chapter 42 - Upper Urinary Tract: TraumaDocument2 pagesChapter 42 - Upper Urinary Tract: TraumaSyahdat NurkholiqNo ratings yet

- Genito Urinary TraumaDocument16 pagesGenito Urinary TraumaAjibola OlamideNo ratings yet

- Complete Blood Picture: 60 Year Female 23321506381Document3 pagesComplete Blood Picture: 60 Year Female 23321506381SilavioNo ratings yet

- Slow Contact Tracing' Blamed For Spread of New CoronavirusDocument6 pagesSlow Contact Tracing' Blamed For Spread of New CoronavirusProdigal RanNo ratings yet

- Corticosteroids 24613Document33 pagesCorticosteroids 24613NOorulain HyderNo ratings yet

- Inappropriate Sinus TachycardiaDocument23 pagesInappropriate Sinus TachycardiaOnon EssayedNo ratings yet

- Paper 1Document11 pagesPaper 1api-499574410No ratings yet

- M5L1 PPT Personal WellnessDocument20 pagesM5L1 PPT Personal WellnessWasif AzizNo ratings yet

- Ludwig Heinrich Bojanus (1776-1827) On Gall's Craniognomic System, Zoology - UnlockedDocument20 pagesLudwig Heinrich Bojanus (1776-1827) On Gall's Craniognomic System, Zoology - UnlockedJaime JaimexNo ratings yet

- Argumentative EssayDocument7 pagesArgumentative EssayHuy BuiNo ratings yet

- Grand Rounds Facial Nerve ParalysisDocument86 pagesGrand Rounds Facial Nerve ParalysisA170riNo ratings yet

- Case Investigation Form Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) : (Check All That Apply, Refer To Appendix 2)Document4 pagesCase Investigation Form Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) : (Check All That Apply, Refer To Appendix 2)john dave rougel ManzanoNo ratings yet

- BASF Excipients For Orally Disintegrating Tablets Make Medication EasyDocument5 pagesBASF Excipients For Orally Disintegrating Tablets Make Medication EasyVõ Đức TrọngNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Rheumatic DiseasesDocument3 pagesAutoimmune Rheumatic DiseasesBuat DownloadNo ratings yet

- Kedaruratan THT I: Dr. Sri Utami Wulandari, SPTHT-KLDocument24 pagesKedaruratan THT I: Dr. Sri Utami Wulandari, SPTHT-KLEvi Liana BahriahNo ratings yet

- Placenta PreviaDocument12 pagesPlacenta Previapatriciagchiu100% (3)

- IJMRBS 530b6369aa161Document16 pagesIJMRBS 530b6369aa161yogeshgharpureNo ratings yet

- IleusDocument10 pagesIleusChyndi DamiNo ratings yet