Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1: Keith Harrison-Broninski

Uploaded by

Antonio VerasOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1: Keith Harrison-Broninski

Uploaded by

Antonio VerasCopyright:

Available Formats

BPTrends

June 2005

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1

Keith Harrison-Broninski

Human Interaction Management (HIM) is a radical new business theory describing how we really work, and how we can be helped to work better. HIM sets the stage for a step change in business practice, by applying process principles to revolutionize the management of collaborative work. These principles require a new approach to process description, management, support and analysis. However well suited current techniques are to dealing with mechanistic and repetitive activities, they are very poorly suited to the dynamic, innovative, interactive behavior typical of humans. People are not programs, and their behavior cannot be properly described, controlled or facilitated using techniques such as BPEL, BPMN or the UML. HIM is the theory required to deal with humanistic processes. It permits dramatic cost savings to be achieved across the board, in any organization no matter its type, by providing a new approach to such everyday activities as work assignment, project management and meeting organization. In a previous article for BP Trends, Managing Process Change? Easy as Pi (and Petri) we looked at some of the high-level management concepts in Human Interaction Management, and showed how both management practices and low-level work activities can be given a formal underpinninga formal underpinning that unifies modern best-of-breed mathematical approaches to process analysis. In the first part of this article we look at the fundamental building block of process modeling in HIMthe Role concept. In the second and concluding part we will introduce a key technique in HIMan enhanced version of the long-established graphical notation known as Role Activity Diagramming (RAD)show why Role Activity Diagrams are appropriate for the description of human activity, and demonstrate how they can be used in seamless conjunction with conventional process modeling via techniques such as the UML to complete the process picture in the enterprise.

Jazz is there and gone. It happens. You have to be present for it. That simple. Keith Jarrett All those working with business processes know that the fundamental problem is that of change. There is just too much of it for convenience. Like it or not, change happensall the time, all over the place. Strategies and policies change, and such high-level change is expensive to implementhowever, it happens relatively infrequently. Structural changes to the organization are more frequent, but can be anticipated, prepared for, budgeted and planned. Staff movement occurs even more often, but we like to think we can manage this kind of changeeven if it is not generally handled as well as we intend, and problems occur all the way down the line as a result, sometimes not manifesting themselves until quite some time after the event. But process changethis is the real nightmare. Not only does it happen all the time, for any number of reasons, but it happens on a case by case basis, as well in general. And there are no generally accepted methods for dealing

Copyright 2005 Keith Harrison-Broninski

www.bptrends.com

BPTrends

June 2005

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1

with it. In other words, we may spend large amounts of time and money preparing a set of process descriptions, and even use these as the basis for computerized process support systems, only to find that the reality of working life has changed, and is now a poor match to the processes thus expressed. There are two fundamental reasons that the processes change. First, a particular process description is no longer right at allsince the time at which it was drawn up, the business has moved on and now does things differently. For example, the process model describing how purchases over a certain amount require approval from a senior manager, but this has been holding up projects, so in practice all project managers just assume approval will be given, and the requisition forms are signed retroactively. Second, people may carry out a particular process in different ways, only some of which match the process description. For example, the process model describing how purchases over a certain amount require approval from a senior manager, but this has been holding up large projects, so in practice certain project managers just assume approval will be given, and the requisition forms are signed retroactively. Note the slight difference in wording! In the second case, it is only for large projects, and certain project managers, that retrospective approval will be given. The change is on a case-by-case basis, rather than across the board. This latter practice, in particular, may never have been officially enshrined in company procedures, just adopted by all concerned as the best and quickest way to get the work done. It is quite possible that the business analysts who did the process modeling were never even informed that such things happen. Some executives may see the removal of such workarounds as a benefit of computerized process support. Whether or not this view has merit, it just doesnt work. People will always find a way to beat the system. Particularly if a group of staff members are frustrated with a process support system that doesnt let them work in the way they wish, they will just work round it exchanging login details, paying for project supplies as out-of-pocket expenses, ordering on account from suppliers, and so on. The only people who believe that process systems have the ability to control people effectively are those who never use them. There is usually an implicit conspiracy of silence among the users of such enterprise software, developed in order to protect their hard-won ability to make the systems do what they want. However, anyone who has implemented enterprise systems, and taken the trouble to look at how they are actually used, knows that users see the constraints enforced by computers as at best an annoyance, and at worst a challenge. Either way, they will bypass or misuse the system in order to get their work done as efficiently as possiblebecause what matters to individuals is not the unalloyed purity of the systems they use, but the results they achieve in their daily work, that have a direct effect on their appraisal outcomes, promotion chances, and salary levels. Hence, if we are to find an effective way of understanding, modeling, managing and supporting human-driven processes, we need to work with people, not impose structures on them that are viewed as hindering the best way to get on with things. Even if you are prepared to ignore basic human psychology, to do anything else aside from accommodating how people actually get work done is just a waste of time. At this point, some readers with executive responsibilities may feel distinctly disinclined to read

Copyright 2005 Keith Harrison-Broninski

www.bptrends.com

BPTrends

June 2005

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1

further! Is anarchy being advocated? Power to the people? A Bolshevik revolution of corporate workers? How are organizations to be controlled if their staff are able to do whatever they feel like? The response to this lies in understanding what needs to remain constant about a process, for purposes of control, and what needs to change in operation, in order to empower people to do their jobs properly. What we are saying is that existing enterprise systems, techniques, and tools have focused to date on the wrong level of process, and attempted to constrain human activities at too detailed a level. In particular, task ordering can't be counted on as a stable component of process structurein any process centered on humans and their interaction. Moreover, we go further, and say that not even the individual tasks themselves are stablethey are dispensed with or added to based on what people perceive to be necessary. In fact, a persons ability to make these kinds of judgments is a major reason that the person was chosen for his or her position in the first place it stems from an individuals deep understanding of the work, and a commitment to getting it done properly and on time. However, this is different from saying that people should be entitled to decide for themselves what the nature and purpose of their work is. It is one thing to decide for yourself how to go about doing your work, and quite another to define the work itself. Defining the work itself involves determining the responsibilities of the workersthe duties they must upholdand the goals they must achievetheir aims and targets. Giving responsibilities and setting goals are executive activities, carried out at a more senior level of authority. Enter the Role concept. Goals and responsibilities are the fundamental aspects of a Role as process participant. In fact, HIM provides a very rich concept of Role, including such key features as a private information space including references to other process objects, and the potential ability to manipulate the process itself. However, goals and responsibilities are effectively what defines the Role. Hence, our claim here boils down to the following: It is an executive matter to determine the Roles in a process, and assign them to appropriate people; but It is for the Users of each Role to decide how best to carry out the work involved something that may vary from person to person, and from case to case.

Lets take as an example a hypothetical investigation by a government agency into cost reduction, featuring Roles including Project Manager, Business Analyst and Accountant. The executive responsible for the process as a wholethe person who instigated it and funded it, a senior civil servant perhapssees his or her self as in charge of the process, as opposed to managing it on a day-to-day basis. The executive neither needs nor wishes day-to-day involvement with every operational detail. What the executive needs is to know that the work will be carried out in a certain waye.g., according to an approved project management methodology such as PRINCE 2ior that the work will deliver results in a specific format requested by, lets say, a politician. In particular, the executive needs to ensure certain specific things. They will engage some, if not all, of the people who will work on the processalmost certainly the project manager, and perhaps others such as analysts and accountantsand be concerned that: The people involved will perform certain Roles, each with its own goals and

www.bptrends.com

Copyright 2005 Keith Harrison-Broninski

BPTrends

June 2005

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1

responsibilities. In order to feel confident of the outcome of the process, an executive sponsor needs to know that people of the right caliber, with the right skills, will be involved, and have agreed to carry out specific duties. The eventual deliverables will meet certain preconditions. It is unlikely that every detail of the deliverable will be specified at an executive level, although executives may need to know that the deliverable will be in a certain format, or contain specific key sections. However, until the process itself has been carried out, it is not appropriate to specify in precise detail the structure of the documents or other deliverables concerneddefining the scope of the problem is a major part of the work of the process itself, and the eventual deliverables will only mirror the understanding developed along the way. The process participants will interact in a way to ensure that their individual contributions combine to produce overall deliverables of the highest possible quality. Although project managers can act to facilitate these interactions, they will not necessarily be empowered to specify how often each person will attend meetings, and what exactly each participant will bring to the table. Such details are often determined by existing, wider-reaching agreements, with, for example, external consultancy organizations. Project management is often concerned more with negotiation and support than with the authority necessary to ensure that the participants in a process are willing to work together in appropriate ways.

In other words, the executive responsible for a process does need to ensure certain things about a process, but none of these concerns are directly task-related. They concern Roles, deliverables and interactions: who will do the work, the general nature of what the workers will produce, and how they will co-operate in doing so. Joining the process as a participant amounts to agreeing that you will contribute specific parts of the overall work. This way of thinking about work provides a more reassuring approach to human-driven process implementation, because it leaves executives with a form of control that they seekand removes from them a level of detail they shouldnt have to worry about. Human Interaction Management (HIM) builds on these insights to provide a comprehensive model of process managementan approach that enables not only managers, but also workers to focus on the work that is rightly their own province. If you are micro-managing your workers down to the level of monitoring each task they carry out, and asking why they have done everything the way they have, you may as well do the work yourselfsaving everyone time in the long run, and certainly causing less annoyance. Executives should be concerned with a higher level of process, one that remains more or less constant because it is part of a wider organizational picture. The principles of HIM implement this separation of control approach to human activity. In general, HIM as a whole is a multi-layered theory, describing process patterns that can be used to understand human working activity, providing modelling tools with which to capture them, techniques with which to manage them, and technology with which to support them. However, at the heart of Human Interaction Management (HIM) there is always the Role conceptthe recognition that a Role is not simply a label applied to a group of activities, but a rich, multilayered representation of a process participant including goals, responsibilities, varied private information resources and so on. All the principles and methods of HIM depend on a rich Role concept as the fundamental means of process description. Unfortunately, however, conventional process modeling techniques universally deal with Roles in

Copyright 2005 Keith Harrison-Broninski

www.bptrends.com

BPTrends

June 2005

Modeling Human Interactions: Part 1

a very limited waysimply as a way to group activities. Not only is this insufficient for our purposes when modeling human interactions, but it falls down completely as a basis for the management of the continual process change that is a feature of human collaboration. A large part of what humans do when they work together is agree on what to do nexthence we need a process modeling technique that can be brought into play as a means of facilitating and implementing such agreements. We need a process modeling technique that: Places Roles center stage, and gives them a rich semantics Is simple and intuitive enough for non-technical people to use Has a natural graphical representation.

In the next part of this article, we will introduce such a graphical techniquea reinvented form of the long-established Role Activity Diagram notationand show how it can be used in conjunction with conventional process modeling to complete the process picture in the enterprise.

1

A project management methodology originally developed by UK government, which has also been found useful in the commercial worldsee the official PRINCE 2 Web site http://www.ogc.gov.uk/prince/

Keith Harrison-Broninski is CTO of Role Modellers Ltd (http://www.rolemodellers.com), author of Human Interactions (http://www.mkpress.com/hi), and contributing author to the new BPMG book In Search Of BPM Excellence (http://www.bpmg.org/insearch_book.php) . He can be reached at khb@rolemodellers.com.

Copyright 2005 Keith Harrison-Broninski

www.bptrends.com

You might also like

- Creating a Project Management System: A Guide to Intelligent Use of ResourcesFrom EverandCreating a Project Management System: A Guide to Intelligent Use of ResourcesNo ratings yet

- Innovating Business Processes for Profit: How to Run a Process Program for Business LeadersFrom EverandInnovating Business Processes for Profit: How to Run a Process Program for Business LeadersNo ratings yet

- Warren Strategy Implementation and Digital Twin Business ModelsDocument7 pagesWarren Strategy Implementation and Digital Twin Business Modelsvenu4u498No ratings yet

- Application of Principles: The Job Design ProcessDocument26 pagesApplication of Principles: The Job Design Processzeeshanshani1118No ratings yet

- Process Management in Human Resources: "Simply, Improvement "Document8 pagesProcess Management in Human Resources: "Simply, Improvement "srdjan90No ratings yet

- BPR (Business Process Reengineering)Document7 pagesBPR (Business Process Reengineering)gunaakarthikNo ratings yet

- AgileHR HRSSI FinalDocument7 pagesAgileHR HRSSI FinalAkansha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Building Information SystemsDocument20 pagesChapter 13 Building Information SystemsNico RolandNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Process Discovery - Laury VernerDocument11 pagesThe Challenge of Process Discovery - Laury VernerEmerson LeiteNo ratings yet

- Networking For DummiesDocument10 pagesNetworking For DummiesAdam AlejeNo ratings yet

- Tip-of-the-Iceberg Syndrome Explained in BPM ProjectsDocument5 pagesTip-of-the-Iceberg Syndrome Explained in BPM ProjectsMohd NasirNo ratings yet

- Overview Article About BPM - BurltonDocument7 pagesOverview Article About BPM - BurltonWillian LouzadaNo ratings yet

- Erp 3rd Assignment - Susanta RoyDocument9 pagesErp 3rd Assignment - Susanta RoySusanta RoyNo ratings yet

- Critical Success Factors of Erp Implementation in PakistanDocument18 pagesCritical Success Factors of Erp Implementation in PakistanPari JanNo ratings yet

- How Do BA's OperateDocument6 pagesHow Do BA's OperatehamedNo ratings yet

- Organic Versus Mechanistic and 6 ORG StuctureDocument3 pagesOrganic Versus Mechanistic and 6 ORG StuctureSuvendran MorganasundramNo ratings yet

- Unit - C: Building Information Systems in The Digital FirmDocument9 pagesUnit - C: Building Information Systems in The Digital FirmdearsaswatNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Downsizing On Corporate CultureDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Downsizing On Corporate Culturesmitamali94No ratings yet

- HR Process Reengineering: Improving Employee Retention Through Effective StrategiesDocument6 pagesHR Process Reengineering: Improving Employee Retention Through Effective StrategiesVivek NerurkarNo ratings yet

- The Six Fallacies of Business Process Improvement: Dominique Vauquier Translated by Jean-Jacques DubrayDocument5 pagesThe Six Fallacies of Business Process Improvement: Dominique Vauquier Translated by Jean-Jacques DubrayWan Sek ChoonNo ratings yet

- Business Process: The Model and The RealityDocument4 pagesBusiness Process: The Model and The RealityJournal of ComputingNo ratings yet

- Execution 1Document6 pagesExecution 1tonks178072No ratings yet

- Change Management Process Research PaperDocument8 pagesChange Management Process Research Papervehysad1s1w3100% (1)

- Operations ManagementDocument50 pagesOperations ManagementpolohachikoNo ratings yet

- Step 7 - Identify Breakthrough OpportunitiesDocument6 pagesStep 7 - Identify Breakthrough OpportunitiesLalosa Fritz Angela R.No ratings yet

- BPR - A Consolidated Approach by Tushar J. ParakhDocument5 pagesBPR - A Consolidated Approach by Tushar J. ParakhTushar ParakhNo ratings yet

- MBA-Semester II Production & Operations ManagementDocument26 pagesMBA-Semester II Production & Operations ManagementJyotsna KapoorNo ratings yet

- Master of Business Administration-MBA Semester IIDocument10 pagesMaster of Business Administration-MBA Semester IIBela JadejaNo ratings yet

- BPM Assignment Final PDFDocument81 pagesBPM Assignment Final PDFSharmishtha Pandey100% (1)

- BPR Chapter1 Concept and Principle Know Where You Are3Document29 pagesBPR Chapter1 Concept and Principle Know Where You Are3Kalai VaniNo ratings yet

- The Process Enterprise: An Executive Perspective: by Dr. Michael HammerDocument17 pagesThe Process Enterprise: An Executive Perspective: by Dr. Michael HammerAnonymous ul5cehNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 Written Discussion QuestionsDocument2 pagesChapter 9 Written Discussion QuestionsMatthew Beckwith100% (7)

- 2 Structural Frame WorksheetDocument4 pages2 Structural Frame Worksheetapi-720145281No ratings yet

- 11FinchRaynor PaperDocument5 pages11FinchRaynor PaperNaokhaiz AfaquiNo ratings yet

- Empirical Modelling for Participative BPRDocument48 pagesEmpirical Modelling for Participative BPRSGNo ratings yet

- Multiproject Management - Problems & Their Solutions: Lead-InDocument3 pagesMultiproject Management - Problems & Their Solutions: Lead-InNageswar ReddyNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document39 pagesUnit 1Thiru VenkatNo ratings yet

- The Manager: 1.1. Short History and DefinitionDocument6 pagesThe Manager: 1.1. Short History and DefinitionDiana ManciNo ratings yet

- Research 2 OdDocument20 pagesResearch 2 OdPlik plikNo ratings yet

- Organizational Change Management Process PDFDocument5 pagesOrganizational Change Management Process PDFmkdev2004@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Business Process ManagementDocument14 pagesBusiness Process ManagementMuhammad AdamNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Performance Management System PDFDocument6 pagesDissertation On Performance Management System PDFPayToWriteAPaperUKNo ratings yet

- RSA Identity MGMT Playbook - JML - Jun 2016Document11 pagesRSA Identity MGMT Playbook - JML - Jun 2016naath.aashokNo ratings yet

- 04 06 ART Process Portfolio Management Rosemann1Document4 pages04 06 ART Process Portfolio Management Rosemann1Mohd SaquibNo ratings yet

- Ogl 481 - Module 2 Structural FrameDocument4 pagesOgl 481 - Module 2 Structural Frameapi-675947871No ratings yet

- Assignment On Change ManagementDocument13 pagesAssignment On Change ManagementAvinash Sarma100% (1)

- How Good Is Your Process Management ApproachDocument7 pagesHow Good Is Your Process Management ApproachIgnacio TorresNo ratings yet

- Organizational Design RefDocument3 pagesOrganizational Design RefDane MorteNo ratings yet

- Capestone Project FIANL - MODELDocument92 pagesCapestone Project FIANL - MODELFráñcisNo ratings yet

- What Is WorkflowDocument8 pagesWhat Is WorkflowLoewelyn BarbaNo ratings yet

- BPMN Process ModellingDocument3 pagesBPMN Process ModellingJane QuitonNo ratings yet

- Business Process ManagementDocument12 pagesBusiness Process ManagementArcebuche Figueroa FarahNo ratings yet

- Methodologies For Business Process Modelling and ReengineeringDocument19 pagesMethodologies For Business Process Modelling and ReengineeringSimon RuoroNo ratings yet

- Reengineering Knowledge Work: Knowledge Management Has Recently Become A Fashionable Concept, Although ManyDocument20 pagesReengineering Knowledge Work: Knowledge Management Has Recently Become A Fashionable Concept, Although ManyVishnuNo ratings yet

- Trends in Human Resource ManagementDocument4 pagesTrends in Human Resource ManagementPreethi SudhakaranNo ratings yet

- Public Sector HR Transformation ArticleDocument4 pagesPublic Sector HR Transformation ArticleShaun DunphyNo ratings yet

- 8020 A New Model For Business Process DesignDocument36 pages8020 A New Model For Business Process DesignIan Ramsay100% (1)

- MS-01 SOLVED ASSIGNMENT 2015Document10 pagesMS-01 SOLVED ASSIGNMENT 2015JasonSpringNo ratings yet

- Theory+ +Students+VersionDocument4 pagesTheory+ +Students+VersionKetaki KolaskarNo ratings yet

- HR systems surveyDocument5 pagesHR systems surveysrraNo ratings yet

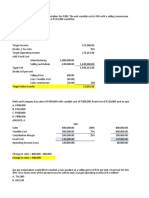

- CVP Solution (Quiz)Document9 pagesCVP Solution (Quiz)Angela Miles DizonNo ratings yet

- Spain Price List With VatDocument3 pagesSpain Price List With Vatsanti647No ratings yet

- (NTA) SalaryDocument16 pages(NTA) SalaryHakim AndishmandNo ratings yet

- Factory Hygiene ProcedureDocument5 pagesFactory Hygiene ProcedureGsr MurthyNo ratings yet

- 1 N 2Document327 pages1 N 2Muhammad MunifNo ratings yet

- The Punjab Commission On The Status of Women Act 2014 PDFDocument7 pagesThe Punjab Commission On The Status of Women Act 2014 PDFPhdf MultanNo ratings yet

- Article 4Document31 pagesArticle 4Abdul OGNo ratings yet

- Hilti X-HVB SpecsDocument4 pagesHilti X-HVB SpecsvjekosimNo ratings yet

- Namal College Admissions FAQsDocument3 pagesNamal College Admissions FAQsSauban AhmedNo ratings yet

- Pyramix V9.1 User Manual PDFDocument770 pagesPyramix V9.1 User Manual PDFhhyjNo ratings yet

- Brightline Guiding PrinciplesDocument16 pagesBrightline Guiding PrinciplesdjozinNo ratings yet

- Cantilever Retaining Wall AnalysisDocument7 pagesCantilever Retaining Wall AnalysisChub BokingoNo ratings yet

- Converting An XML File With Many Hierarchy Levels To ABAP FormatDocument8 pagesConverting An XML File With Many Hierarchy Levels To ABAP FormatGisele Cristina Betencourt de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Safety interlock switches principlesDocument11 pagesSafety interlock switches principlesChristopher L. AlldrittNo ratings yet

- AutocadDocument8 pagesAutocadbrodyNo ratings yet

- Using The Marketing Mix Reading Comprenhension TaskDocument17 pagesUsing The Marketing Mix Reading Comprenhension TaskMonica GalvisNo ratings yet

- Iqvia PDFDocument1 pageIqvia PDFSaksham DabasNo ratings yet

- CCTV8 PDFDocument2 pagesCCTV8 PDFFelix John NuevaNo ratings yet

- Dubai Healthcare Providers DirectoryDocument30 pagesDubai Healthcare Providers DirectoryBrave Ali KhatriNo ratings yet

- PHASE 2 - Chapter 6 Object ModellingDocument28 pagesPHASE 2 - Chapter 6 Object Modellingscm39No ratings yet

- Job Hazard Analysis TemplateDocument2 pagesJob Hazard Analysis TemplateIzmeer JaslanNo ratings yet

- Terminología Sobre Reducción de Riesgo de DesastresDocument43 pagesTerminología Sobre Reducción de Riesgo de DesastresJ. Mario VeraNo ratings yet

- AnswersDocument3 pagesAnswersrajuraikar100% (1)

- C - Official Coast HandbookDocument15 pagesC - Official Coast HandbookSofia FreundNo ratings yet

- WSM 0000410 01Document64 pagesWSM 0000410 01Viktor Sebastian Morales CabreraNo ratings yet

- Anomaly Sell Out Remap December 2019 S SUMATRA & JAMBIDocument143 pagesAnomaly Sell Out Remap December 2019 S SUMATRA & JAMBITeteh Nha' DwieNo ratings yet

- ETP Research Proposal Group7 NewDocument12 pagesETP Research Proposal Group7 NewlohNo ratings yet

- Chirala, Andhra PradeshDocument7 pagesChirala, Andhra PradeshRam KumarNo ratings yet

- Presentation Pineda Research CenterDocument11 pagesPresentation Pineda Research CenterPinedaMongeNo ratings yet

- Gigahertz company background and store locationsDocument1 pageGigahertz company background and store locationsjay BearNo ratings yet