Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bibliografia Codigo Puente

Uploaded by

Alonso Mateos RodriguezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bibliografia Codigo Puente

Uploaded by

Alonso Mateos RodriguezCopyright:

Available Formats

1. Resuscitation. 2010 Apr;81(4):383-7. Epub 2009 Dec 14.

Cardiac arrest in the catheterisation laboratory: a 5-year experience of using mechanical chest compressions to facilitate PCI during prolonged resuscitation efforts. Wagner H, Terkelsen CJ, Friberg H, Harnek J, Kern K, Lassen JF, Olivecrona GK. Department of Cardiology, Lund University Hospital, 221 85 Lund, Sweden. henrik.wagner@skane.se Comment in Resuscitation. 2010 Apr;81(4):371-2. PURPOSE: Lengthy resuscitations in the catheterisation laboratory carry extremely high rates of mortality because it is essentially impossible to perform effective chest compressions during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of a mechanical chest compression device, LUCAS, in the catheterisation laboratory, in patients who suffered circulatory arrest requiring prolonged resuscitation. MATERIALS AND METHODS: The study population was comprised of patients who arrived alive to the catheterisation laboratory and then required mechanical chest compression at some time during the angiogram, PCI or pericardiocentesis between 2004 and 2008 at the Lund University Hospital. This is a retrospective registry analysis. RESULTS: During the study period, a total of 3058 patients were treated with PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) of whom 118 were in cardiogenic shock and 81 required defibrillations. LUCAS was used in 43 patients (33 STEMI, 7 non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), 2 elective PCIs and 1 patient with tamponade). Five patients had tamponade due to myocardial rupture prior to PCI that was revealed at the start of the PCI, and all five died. Of the remaining 38 patients, 1 patient underwent a successful pericardiocentesis and 36 were treated with PCI. Eleven of these patients were discharged alive in good neurological condition. CONCLUSION: The use of mechanical chest compressions in the catheterisation laboratory allows for continued PCI or pericardiocentesis despite ongoing cardiac or circulatory arrest with artificially sustained circulation. It is unlikely

that few, if any, of the patients would have survived without the use of mechanical chest compressions in the catheterisation laboratory.

1. Coron Artery Dis. 2008 Dec;19(8):615-8. Outcome of emergency percutaneous coronary intervention for acute STelevation myocardial infarction complicated by cardiac arrest. Mager A, Kornowski R, Murninkas D, Vaknin-Assa H, Ukabi S, Brosh D, Battler A, Assali A. Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories, Department of Cardiology, Rabin Medical Center, Petach Tikva, Israel. avivm@clalit.org.il BACKGROUND: The poor prognosis of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest complicating acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) may at least partly be explained by the common presence of cardiogenic shock. This study examined the impact of emergency primary PCI on outcome in patients with STEMI not complicated by cardiogenic shock who were resuscitated from cardiac arrest. METHODS AND RESULTS: The study group included 948 consecutive patients without cardiogenic shock who underwent emergency primary PCI from 2001 to 2006 for STEMI. Twenty-one of them were resuscitated from cardiac arrest before the intervention. Data on background, clinical characteristics, and outcome were prospectively collected. There were no differences between the resuscitated and nonresuscitated patients in age, sex, infarct location, or left ventricular function. The total one-month mortality rate was higher in the resuscitated patients (14.3 vs. 3.4%, P=0.033), but noncardiac mortality accounted for the entire difference (14.3 vs. 1.2%, P=0.001), whereas cardiac mortality was similarly low in the two groups (0 vs. 2.0%, P=NS). Predictors of poor outcome in the resuscitated patients were older age (r=0.47, P=0.032), unwitnessed sudden death (r=0.44, P=0.04), longer interval between onset of cardiac arrest and arrival of a mobile unit (r=0.67, P=0.001) or to spontaneous circulation (r=0.65, P=0.001), low glomerular filtration rate (r=-0.50, P=0.02), and the initial thrombolysis in myocardial infarction grade of flow (r=-0.51, P=0.017).

CONCLUSION: Emergency PCI for STEMI not associated with cardiogenic shock exerts a similar effect on cardiac mortality in patients who were resuscitated from cardiac arrest and in those without this complication. The higher allcause mortality rate among resuscitated patients is explained by noncardiac complications.

1. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008 Jun;14(3):287-91. Urgent invasive coronary strategy in patients with sudden cardiac arrest. Noc M, Radsel P. Center for Intensive Internal Medicine, University Medical Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia. marko.noc@mf.uni-lj.si PURPOSE OF REVIEW: To review the evidence on urgent coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention after resuscitated cardiac arrest and during ongoing cardiocerebral resuscitation. RECENT FINDINGS: In almost 450 patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction after reestablishment of spontaneous circulation, success rate of primary percutaneous coronary intervention was 89%. Survival rates in conscious patients after reestablishment of spontaneous circulation were comparable to patients without preceding cardiac arrest while in comatose patients, survival was 57% and survival with acceptable neurological outcome 38%. Nonrandomized trials in 106 comatose survivors of cardiac arrest indicate that urgent invasive coronary strategy can be safely combined with mild induced hypothermia. Percutaneous coronary intervention is also feasible in patients undergoing cardiocerebral resuscitation. In 34 reported patients, the success rate of percutaneous coronary intervention was 88% and survival to hospital discharge 41%. SUMMARY: Urgent coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention should be attempted in conscious patients after reestablishment of spontaneous circulation similarly as in patients with acute coronary syndromes without preceding cardiac arrest. In comatose survivors, urgent coronary strategy is reasonable if acute ischemic cause is suspected and if there is realistic hope

for neurological recovery that should be facilitated with mild induced hypothermia. Urgent coronary invasive strategy may be successful also during ongoing resuscitation in selected patients without advanced heart diseases and significant comorbidities.

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Human Magnet Syndrome Why We Love PeDocument8 pagesThe Human Magnet Syndrome Why We Love Peapi-316440587No ratings yet

- Full Medical Examination Form For Foreign Workers: Work Pass DivisionDocument1 pageFull Medical Examination Form For Foreign Workers: Work Pass Divisionkarthik.swamyNo ratings yet

- QB BT PDFDocument505 pagesQB BT PDFنيزو اسوNo ratings yet

- Program Implementation With The Health Team: Packages of Essential Services For Primary HealthcareDocument1 pageProgram Implementation With The Health Team: Packages of Essential Services For Primary Healthcare2A - Nicole Marrie HonradoNo ratings yet

- U.S. Fund For UNICEF Annual Report 2010Document44 pagesU.S. Fund For UNICEF Annual Report 2010U.S. Fund for UNICEF100% (1)

- Prioritization - FNCPDocument10 pagesPrioritization - FNCPJeffer Dancel67% (3)

- BioInformatics Quiz1 Week14Document47 pagesBioInformatics Quiz1 Week14chahoub100% (4)

- DASH Questionnaire Disability Arm Shoulder HandDocument3 pagesDASH Questionnaire Disability Arm Shoulder HandChristopherLawrenceNo ratings yet

- Illness in The NewbornDocument34 pagesIllness in The NewbornVivian Jean TapayaNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy in Nursing HomesDocument7 pagesMusic Therapy in Nursing Homesapi-300510538No ratings yet

- Week 1 - NCMA 219 LecDocument27 pagesWeek 1 - NCMA 219 LecDAVE BARIBENo ratings yet

- Kuwait Pediatric GuideLinesDocument124 pagesKuwait Pediatric GuideLinesemicurudimov100% (1)

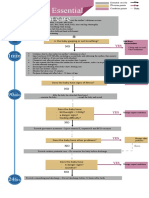

- Algorithm: Essential Newborn Care: Is The Baby Gasping or Not Breathing?Document1 pageAlgorithm: Essential Newborn Care: Is The Baby Gasping or Not Breathing?Dela cruz KimberlyNo ratings yet

- Cast and SplintsDocument58 pagesCast and SplintsSulabh Shrestha100% (2)

- Maxime Gorky and KingstonDocument433 pagesMaxime Gorky and KingstonBasil FletcherNo ratings yet

- Deadly Deception - Robert WillnerDocument303 pagesDeadly Deception - Robert Willnerleocarvalho001_60197100% (5)

- Slcog Abstracts 2012Document133 pagesSlcog Abstracts 2012Indika WithanageNo ratings yet

- Therapy Enhancing CouplesDocument22 pagesTherapy Enhancing CouplesluzNo ratings yet

- Guidelines EuromyastheniaDocument4 pagesGuidelines Euromyastheniadokter mudaNo ratings yet

- Meralgia ParaestheticaDocument4 pagesMeralgia ParaestheticaNatalia AndronicNo ratings yet

- Tufts by Therapeutic ClassDocument56 pagesTufts by Therapeutic ClassJames LindonNo ratings yet

- 2012 NCCAOM Herbal Exam QuestionsDocument10 pages2012 NCCAOM Herbal Exam QuestionsElizabeth Durkee Neil100% (2)

- PowersDocument14 pagesPowersIvan SokolovNo ratings yet

- Tamiflu and ADHDDocument10 pagesTamiflu and ADHDlaboewe100% (2)

- CATHETERIZATIONDocument3 pagesCATHETERIZATIONrnrmmanphdNo ratings yet

- Bedwetting in ChildrenDocument41 pagesBedwetting in ChildrenAnkit ManglaNo ratings yet

- Paper Roleplay Group 3Document7 pagesPaper Roleplay Group 3Endah Ragil SaputriNo ratings yet

- Msds ChloroformDocument9 pagesMsds ChloroformAhmad ArisandiNo ratings yet

- IMTX PatentDocument76 pagesIMTX PatentCharles GrossNo ratings yet

- The Effects of The Concept of Minimalism On Today S Architecture Expectations After Covid 19 PandemicDocument19 pagesThe Effects of The Concept of Minimalism On Today S Architecture Expectations After Covid 19 PandemicYena ParkNo ratings yet