Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kunqu

Uploaded by

api-38206270 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

48 views15 pagesin English, Chinese traditional operas ppt no2, made by a friend

Original Title

kunqu

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentin English, Chinese traditional operas ppt no2, made by a friend

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

48 views15 pagesKunqu

Uploaded by

api-3820627in English, Chinese traditional operas ppt no2, made by a friend

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

Kunqu is one of the oldest and most refined

styles of traditional Chinese theatre performed

today. It is a synthesis of drama, opera, ballet,

poetry recital, and forms of Chinese theatrical

performances such musical recital, which also

draws on earlier century B.C. or even earlier.

In a Kunqu performance as mime, farce,

acrobatics, ballad recital, and medley, some of

which go back to the third, recitative is

interspersed with arias sung to traditional

melodies, called qu-pai. Each word or phrase

is also expressed by a stylized movement or

gesture that is essentially part of a dance.

Even casual gestures must be precisely

executed and timed to coordinate with the

music and percussion. The refinement of the

movement is further enhanced with stylized

costumes that also serve as simple props.

Strictly speaking, the name Kunqu refers to the

musical element of this art form. Kun refers to

Kunshan and qu means music. The name derives

from the fact that one of the principal types of

regional music that went into the making of Kunqu

came from the district of Kunshan near Suzhou. This

type of regional music goes back to the 14th century.

It was given shape in the 16th century by Wei

Liangfu and others, who combined it with three other

forms of southern music and with northern tunes

from the drama of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368).

Wei Liangfu and his collaborators standardized the

rules of rhyme, tones, pronunciation, and notation,

making it possible for this regional form of music to

become a national standard. By the end of the 16th

century, Kunqu spread from the Suzhou region to

the rest of China, and for the next 200 years was the

most prestigious form of Chinese drama.

Kunqu is first and foremost a

performing art. Performances are

valued not only for their riveting

synthesis of drama, singing and

dancing, but also for the literary

refinement of their poetic libretto. The

plot is usually familiar to the

audience, or else made available

through a prose summary. In fact,

most Kunqu plays would take several

days to perform in their entirety. So

any given performance generally

consists of a few selected scenes

from one or more well known plays.

王世贞的《鸣凤记》,汤显祖的《牡丹亭》、《紫钗记》、《邯鄣记》、

《南柯记》,沈璟的《义侠记》等。高濂的《玉簪记》,李渔的《风筝误》

,朱素臣的《十五贯》,孔尚任的《桃花扇》,洪昇的《长生殿》,另外还

有一些著名的折子戏,如《游园 惊梦》、《阳关》、《三醉》、《秋江》、

《思凡》、《断桥》等。

There are two, easily

distinguished, styles of text

and music. Arias, which are

sung and accompanied by the

orchestra, are elaborate

poems of high literary quality.

Prose passages (monologues

and dialogues) are neither

sung nor spoken but chanted

in a stylized fashion

comparable to the recitative of

Western opera. Sometimes

there is a combination of the

two styles: one of the

characters sings while another

one chants at the same time.

Kunqu music is based on the "qupai "

principle. The poetic passages of the

play are written to fit an a sequence of

tunes, known as qu-pai, chosen from an

existing repertory. Since Chinese is a

tonal language, there is a delicate

relation between words and tunes. Every

word has a "melody", and the musical air

must be superimposed on the word

melody, without interfering with it. Only

after the main and subordinate qu-pai

were selected did the author begin to

compose the libretto to match the

musical structure.

In a Kunqu performance,

three media work

simultaneously and in

harmony to convey the

meaning and desired

esthetic effect: music,

words, and dance. An

accomplished Kunqu

performer must master the

special styles of singing

and dance movement to

convey the meaning and

desired esthetic effect.

The language of Kunqu is not the dialect of

Kunshan or Suzhou, nor is it standard Mandarin. It

is an artificial stage language, a modified

Mandarin with some features of the local dialect.

Since the language in which Kunqu plays are

written has eight tones, the composition of the

libretto was a complex undertaking. Typically, the

author had to continuously refine the libretto and

musical notes until the word melody of libretto and

the musical melody of qu-pai fell into harmony. In

fact, an ideal harmony was seldom fully realized.

Since the creation of a new Kunqu play presented

such a great challenge to the author, almost all

Kunqu playwrights were poets. The libretto

typically has significant esthetic value in its own

right, and many Kunqu libretto are highly regarded

as examples of refined Chinese literature.

In addition to music and words, dance

movements and highly stylized gestures

form an integral part of the performance.

As in classical ballet, the whole body is

engaged, but the movement is much more

grounded. The movements convey an

intricate language of gestures and body

movements that is similar but much more

complex and extensive than the mime in

classical ballet. Although the meaning of

some movements is immediately

understood even by the uninitiated, other

movements are stylized and conventional,

involving not only the body but also the

costume (especially the sleeves) and props

held in the hand, such as a fan.

As in all traditional Chinese theater,

Kunqu uses a minimum of props and

scenery, which permits the

performers to more easily express

their stage movements in the form of

dance. There is no curtain, and few

props: sometimes a table and a

chair. The performers appeal to the

audience‘s imagination and conjure

up a scene or a setting (such as a

door, a horse, a river, a boot) with

words, gestures, and music. The

costumes are elaborate exaggerated

versions of the style of dress during

the Ming Dynasty and make no

attempt to fit the time or place of the

action. For instance, in many roles,

the performers wear robes with

extremely long white sleeves call

“water sleeves”.

The costumes and simple

props often convey additional

information about the

characteristic of the character.

For instance, peonies on a

young man's robe might

indicate a playboy, or carrying

a magnifying glass might

indicate social blindness. A

Buddhist nun always carries

duster to ward off evil spirits.

The meaning and accessibility of Kunqu

performances are further enhanced by

well defined role types. These roles differ

not only in the type of character - young

man, young woman, clown, etc -- but also

in the vocal requirements and the form in

which the body is engaged. In fact, the

stylized movement associated with each

role type constitutes an art form in itself.

In fact, the development of

Kunqu theater in the second half

of the sixteenth century marked

the beginning of the Chinese

xiqu era, from which all other

forms of Chinese theatre

performed today evolved.

Consequently, many Kunqu

plays have been adapted for

other types of xiqu.

Kunqu remains the most refined

and literary of all forms of Chinese

xiqu, but the most popular form of

xiqu in China today is Beijing

opera. It has retained many of the

features of Kunqu theater, but uses

fewer and a less sophisticated set

of melodies.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Building Great Sentences - Exploring The Writer's Craft by Brooks Landon - ReviewDocument5 pagesBuilding Great Sentences - Exploring The Writer's Craft by Brooks Landon - Reviewi KordiNo ratings yet

- Led Fundamentals: Luminous EfficacyDocument10 pagesLed Fundamentals: Luminous EfficacyKalp KartikNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Peking OperaDocument41 pagesPeking Operaapi-3820627100% (2)

- Citizen Kane Script by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles PDFDocument135 pagesCitizen Kane Script by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles PDFFlavio Roberto Mota100% (2)

- PerfumeDocument70 pagesPerfumeapi-382062750% (2)

- Dennis MacDonald - Semeia 38Document117 pagesDennis MacDonald - Semeia 38pishoi gerges100% (1)

- Lecture # 2Document41 pagesLecture # 2Diosary TimbolNo ratings yet

- Short StoriesDocument4 pagesShort StoriesJoana CalvoNo ratings yet

- Meeting The Client-2Document4 pagesMeeting The Client-2Smith Snow100% (3)

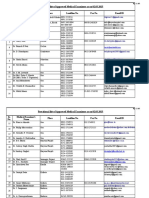

- Hospital List March 92012Document198 pagesHospital List March 92012Prashant Ingawale100% (1)

- Succeed in Cambridge Pet 10 Practice tests-KEYS PDFDocument2 pagesSucceed in Cambridge Pet 10 Practice tests-KEYS PDFTienNguyen50% (6)

- 国际音标(小课本)Document3 pages国际音标(小课本)api-3820627100% (1)

- 几张不可思议奇异的照片Document16 pages几张不可思议奇异的照片api-3820627No ratings yet

- IPA ChineseDocument1 pageIPA Chineseapi-3820627No ratings yet

- ShoesDocument52 pagesShoesapi-3820627No ratings yet

- Medieval EuropeDocument10 pagesMedieval Europeapi-3820627No ratings yet

- JewelsDocument39 pagesJewelsapi-3820627100% (1)

- Chinese OperasDocument10 pagesChinese Operasapi-3820627No ratings yet

- DesdemonaDocument16 pagesDesdemonaapi-3820627No ratings yet

- Japanese FestivalsDocument81 pagesJapanese Festivalsapi-3820627100% (1)

- Ages of EmpiresDocument55 pagesAges of Empiresapi-3820627No ratings yet

- ClothingDocument28 pagesClothingapi-38206270% (1)

- AccoutermentDocument36 pagesAccoutermentapi-3820627No ratings yet

- Academy AwardsDocument16 pagesAcademy Awardsapi-3820627No ratings yet

- Per 101808Document388 pagesPer 101808ankitch123No ratings yet

- SS Experiment Love Camp (1976) BRRip 720p x264 (Dual Audio) (Italian + English) - Prisak (HKRG) .MKVDocument3 pagesSS Experiment Love Camp (1976) BRRip 720p x264 (Dual Audio) (Italian + English) - Prisak (HKRG) .MKVArsalanNo ratings yet

- Elapsed Time Word Problems TV Show WorksheetDocument2 pagesElapsed Time Word Problems TV Show WorksheetmarialisaNo ratings yet

- Name Danish Reza: Sub Retail MGT - MBA 2 - Sem: Faculty Shalini SrivastavDocument13 pagesName Danish Reza: Sub Retail MGT - MBA 2 - Sem: Faculty Shalini SrivastavdanishrezaNo ratings yet

- Recruitment of Assistant-2019: Preliminary Examination Shortlisted CandidatesDocument99 pagesRecruitment of Assistant-2019: Preliminary Examination Shortlisted CandidatesGaurav RathoreNo ratings yet

- The Spiritual Vessel (Kli)Document1 pageThe Spiritual Vessel (Kli)Carla MissionaNo ratings yet

- SST (Sci) Math Physics Kohat MaleDocument4 pagesSST (Sci) Math Physics Kohat MaleLuckii BabaNo ratings yet

- Stewardship 1950Document40 pagesStewardship 1950IRASDNo ratings yet

- Spanish influences on Philippine art and musicDocument1 pageSpanish influences on Philippine art and musicSarah Jane PescadorNo ratings yet

- How Does A Tree Grow?: Glossary of Tree TermsDocument3 pagesHow Does A Tree Grow?: Glossary of Tree TermsecarggnizamaNo ratings yet

- Classical Studies Catalog 2017Document40 pagesClassical Studies Catalog 2017amfipolitisNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation of Public Lighting in Novi Sad, SerbiaDocument72 pagesRehabilitation of Public Lighting in Novi Sad, SerbiaVladimir ĐorđevićNo ratings yet

- Leave RecordDocument50 pagesLeave RecordDiyanaNo ratings yet

- The Doric OrderDocument3 pagesThe Doric OrdervademecumdevallyNo ratings yet

- Movement Versus Activity Heidegger S 1922 23 Seminar On Aristotle S Ontology of Life PDFDocument21 pagesMovement Versus Activity Heidegger S 1922 23 Seminar On Aristotle S Ontology of Life PDFRolando Gonzalez PadillaNo ratings yet

- Van Wyke - Imitating Bodies and ClothesDocument17 pagesVan Wyke - Imitating Bodies and ClotheslucykentNo ratings yet

- KTP Rorel INkhawm ProgrammeDocument2 pagesKTP Rorel INkhawm ProgrammeLr VarteNo ratings yet

- Cardinal Direction: Earth Magnetic CompassDocument1 pageCardinal Direction: Earth Magnetic CompassTeodor NastevNo ratings yet

- List Provisional Medicalexaminer 020315Document10 pagesList Provisional Medicalexaminer 020315Arnav JoshiNo ratings yet

- Doctor 8Document16 pagesDoctor 8Pankaj GuptaNo ratings yet

- English 6Document3 pagesEnglish 6PrinsesangmanhidNo ratings yet